Editor’s note: I’d like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Armand Legrand for translating this interview from the Spanish and making this exchange possible.

George Salis: Your father, Pere de Palol, was an archeologist. Did his work in this field have an effect on you during childhood? Do you believe there is some overlap or a bridge between your father’s passion for archeology and your passion for architecture and literature?

Miquel de Palol: Without a doubt. Whether one is conscious of it or not, childhood environment has an effect, and often even more so if one rejects it than if one accepts it. But one constructs one’s own story about oneself, and the effect is, to say the least, debatable. My father and my mother had a very strong character, and immediately felt I must make my own way, which doesn’t prevent me from recognizing and being grateful for the opportunity to have access to classical culture and a way of understanding intellectual activity. This is something I have become more aware of over the years.

GS: In the film Columbus (directed by Kogonada), a character references a quote by the American architect James Polshek: “Architecture is a healing art.” I’ve heard this said of literature. Do you think this sentiment is true of both literature and architecture? Why or why not?

MP: It seems to me too broad a statement to make a valuation of in a few words. It depends on what architecture, including the context, and depends on what literature. Literature and architecture are disciplines with many artistic aspects in common but with a substantial difference. People live in a house, but not in a book, except as a metaphor, which is beside the point. Currently, humans can’t live without houses, but (whether it’s fortunately or unfortunately is up to each of us) we can live without books.

GS: Do you believe in an “Architect” of existence, or do you consider the cosmos’ appearance of organization illusory?

MP: I try to embrace skepticism or, if you prefer, systematic doubt [translator’s note: I believe he is referring here to Cartesian doubt]. Despite scientific advancements, we humans continue to tend to identify any being capable of self-consciousness and decision-making with ourselves. The gods are very human, including their arbitrariness and caprices. We would have to delve further into whether we can assign the title of “Architect of existence” to the expansion of energy. On the other hand, I wouldn’t dare assert that reality as a whole is not illusory.

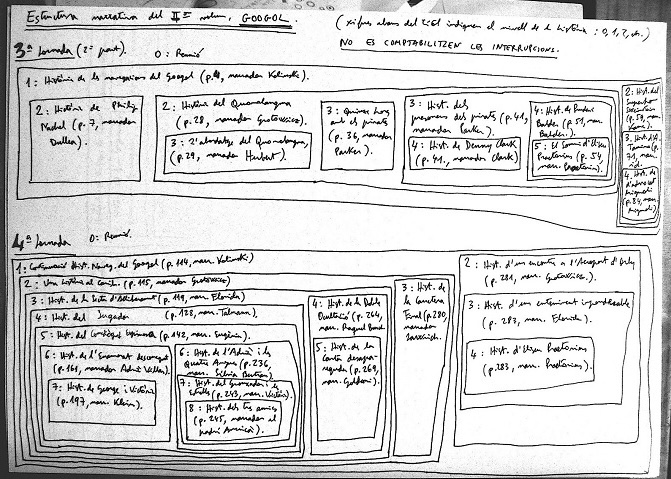

GS: The construction of El jardí dels set crepuscles (The Garden of Seven Twilights, translated from the Catalan by Adrian Nathan West) features eight nested narratives. What informed your vision of this structure? Did you look toward other nested forms of literature, such as The Thousand and One Nights?

MP: Including stories inside of other stories has a great tradition beyond The Thousand and One Nights. The Decameron, Stevenson’s The New Arabian Nights, and many others. The model closest to The Garden of Seven Twilights is The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by Jan Potocki, from which I took the device of having each story be an entity of its own, able to be read separately as a tale, but simultaneously the set of tales, as in a mosaic, form a single story in itself.

GS: The novel is a fairly amorphous art form because its construction can vary wildly. From the highly digressive Moby Dick and the “lopsided Sierpinski gasket” of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest to the dodecahedron of your novel The Troiacord, the permutations are practically endless. Can you reflect on this? Also, is the freedom of this form partly why you transitioned from poetry to novels?

MP: Contrary to popular belief, the problem of the novelist when tackling a new piece is not panic in the face of blank paper. Anything, including absence, is material for thousands of pages. A writer who manifests a lack of inspiration (in which I don’t believe) surely hasn’t found the best medium for self-expression. I see the act of narration as seated on a three-legged stool: planning, discarding, and ordering. In relation to the transition from poetry to the novel, it happened naturally and logically. To express what I wanted at that moment I needed another device and I found it. But I haven’t stopped writing and publishing poetry.

GS: Speaking of The Troiacord, an English translation of this five-volume work is underway. Do you have any expectations or hopes regarding how English-speaking readers will react to it? Is there a way for readers to prepare, or would it be better to dive into the novel immediately?

MP: I feel skeptical (again) about indications and guides regarding reading, among other things, because the reading public is very diverse, and an aspect that may attract some can scare others away. The experience with this edition of The Garden of Seven Twilights is that part of the North American public reads with much intellectual freedom, without dragging the shadows and prejudices that sometimes hinder European readers. This is not to say that one group is better than the other, they are simply different. In this sense, and with all possible prudence, I have good expectations with the coming edition of El Troiacord. By the way, it won’t be seven volumes; five will be enough.

GS: Aside from El jardí dels set crepuscles (The Garden of Seven Twilights), if you could translate one of your novels into all languages, which would you choose and why?

MP: One always has a special affection for the last child. It would be Boötes. [About this 1,280-page apocalyptic novel, Palol told Ara: “At the beginning it seems clear who is in charge, but later it is not. At this point, the novel works as an allegory of our present, in which politicians no longer decide anything, they are employees of the true masters. In the 19th century we knew who these masters were. Now we don’t. We can’t tell if the rich Forbes are really in charge or if there is someone even more powerful than them behind it. The people cannot revolt because we no longer know who is guilty. […] “In the center [of the novel] is a huge void, which would be the self that represents the main character. I named it Arthur because it is the main star of the constellation Boötes….”]

GS: You became president of the Associació d’Escriptors en Llengua Catalana (Association of Collegiate Writers of Catalonia) in 2011. Can you tell me some of the work you’ve done in this position and about the organization in general?

MP: ACEC is an association for the defense of writers’ rights. I took this position to help in whatever way I could and also as a way to get out of the isolated tower that is the poet’s study. I have fond memories of that period, which allowed me to know and befriend many valuable people, participate actively in discussing new laws, and organize literary events.

GS: How would you compare and contrast Catalan and Spanish? What about English?

MP: Catalan and Spanish are Romance languages that are quite close, and with mutual influences. All Catalan people know and speak Spanish, but very few Spanish people know and speak Catalan. But that is entirely a sociopolitical matter that has little to nothing to do with literature. Italian, French, Sardinian, Corsican, Romansh, and Romanian (with a great variety of dialects) belong to the same group, and it’s relatively easy, with a minimum of good will, for speakers of these languages to understand each other. English belongs to another linguistic family, but has a feature in common with Catalan: both are the most monosyllabic languages of their environment, which entails an important advantage for translation, especially in poetry.

GS: What is a poetry collection or novel that you’ve read and think deserves more readers? Why?

MP: The world is immersed in the replacement of literary prescription by the market, which, as I see it, will be devastating for writing as an art. Mere entertainment will remain, which is to say, nothing. Since the question mentions “deserving,” I don’t have any doubts: the collections of Greek and Latin classics.

GS: Can you tell me about some of your science fiction influences? Are there any particular books or films that you’ve found especially inspirational?

MP: As I see it, there are extraordinary writers who far transcend the realm of science fiction. In first place I would highlight Stanislav Lem, a great storyteller of “the other,” who delves deeply like few others into the essence of humanity. I would place Robert Heinlein, Arthur Clarke, Philip K. Dick, Bradbury, Herbert, and Asimov in similar categories. Film-wise, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Solaris (the original Tarkovsky version), Alien, Total Recall, and on another note, Star Trek.

GS: What projects are you currently working on?

MP: A new poetry book just came out, Dies Claríssims de Síria.I’m finishing a new novel, Abans Més Que Encara, and preparing the next, Viatge al Tibet, in addition to two studies in collaboration: one about music (concretely, about the reception of Bach’s work across time), another about architecture.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

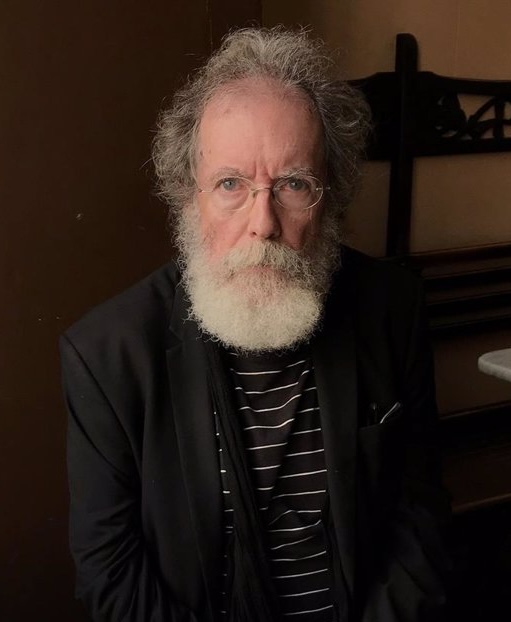

Miquel de Palol was born in Barcelona in 1953 and is one of the most respected voices of contemporary Catalan letters. An architect by trade, he began publishing poetry at 19, and averaged a book of verse per year before bringing out El jardí dels set crepuscles, the novel many consider to be his masterpiece, in 1989. The author claims he considers this first work of narrative fiction a continuation of themes pursued in his earlier poetry. Remarkably prolific, Palol has published some forty books, including works of short fiction, children’s stories, and essays, and is a frequent contributor to the Spanish and Catalan press.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.