I never thought watching an anti-war movie would have me pining for the return of a fascist. But All Quiet on the Western Front could have used someone like Ezra Pound, not for his brown shirt but for his red pen. It was powerful and visceral. And it was too long. It made me want to run out into the streets carrying a sign saying: End War Now…and end movies sooner.

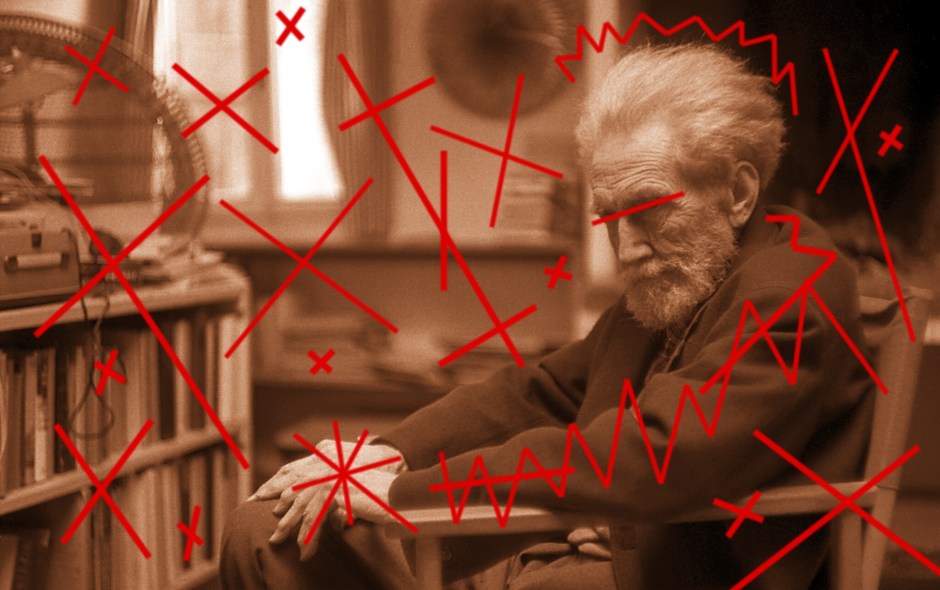

What makes a good editor? A certain objectivity, distance, ruthlessness? One of our greatest American poets and editors, Pound spent most of his life distant, away from America, and a considerable part of that as a mouthpiece for Mussolini.

Last summer I visited Brunnenburg castle in Tyrol, Italy, where Pound went to live with his daughter in 1958. He had just been released from the U.S. after serving a sentence for treason. Editing is as much about what to leave in as what to take out and the talent for that balancing act is not genetic. The castle is still owned by Mary de Rachewiltz, his daughter, and the museum inside it is personal; it doesn’t show the whole difficult picture. There is hardly a mention of his problematic affair with fascism. But more surprising is that though the museum is owned by a woman, it lacks not just a woman’s touch but a woman’s presence. It is overwhelmingly a men’s club, the wooden walls plastered with pictures of male contemporaries of Pound. Women are mentioned in displays of documents and memorabilia in footnotes at best, admired as footstools at worst.

But Pound’s preserved workspace and library are maybe the most spectacular in all of literature. His desk sits before a wall that is mostly window. It overlooks the brutal mountains of South Tyrol, crags of bare rock and sharp edges. His poetry too is like that, stripped down to its angular frame. His most well-known poem, In a Station of the Metro, is short and to the point:

The apparitions of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet black bough.

The compactness of imagism is worth a thousand words. The museum is cluttered with too many of them, documents and pictures in an order I couldn’t comprehend. Again, it is chock-full of literary giants but absent of giantesses. There is no mention of his relationship with Hilda Doolittle, for example, who was influenced by Pound and most likely influenced him in return. In her poem Heat, she wrote:

fruit cannot fall into heat

that presses up and blunts

the points of pears

and rounds the grapes.

She was spare and unsparing. Her name is synonymous with imagism. And her name was famously abbreviated by Pound to H.D. And he’s also well-known as the hatchet man to T.S. Eliot, literally trimming the waste on the most famous of modernist epics. Under Pound’s knife, The Waste Land went from 1,000 lines to 434. It’s wrong to say Eliot would have been nothing without Pound. But it’s true he would have been too much. Author of The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupery dabbled in allegory, but he was an imagist at heart when he wrote: “Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

Ezra Pound was an expert at stripping away the unnecessary. Unfortunately, he also favored a reprehensible form of government that stripped away rights and freedoms. And maybe that’s how we see editors in this day and age, as taking hard-earned things away. But if we want to make works of art, especially movies great again, we need to make them shorter. Isn’t it ironic that as attention spans are arguably shrinking to goldfish proportions, blockbusters are busting past two hours?

As an Ozempic nation, we wish to see our own selves stripped down to our minimum weight and superbly toned. Our entertainers famously drink only bone broth for lunch, but we’ve allowed our entertainment industry to balloon to unhealthy proportions, bulking up on creative talent but skipping editors as if they were healthy but unappealing snacks. And then we give prizes for just showing up. The coveted Oscar. And the audience is the biggest loser.

War is hell, but the creators of All Quiet on the Western Front also made it disturbingly beautiful. They deserved the Oscar for Cinematography. They also deserve a reprimand for letting the movie (like war) drag on too long. There was enough drama built into the first two hours of All Quiet for a lifetime of nightmares. There was no need for the manufactured tension of the last half hour, the gratuitous farmhouse scene, or the contrived battle that veered sharply from historical events and from the book written by Erich Maria Remarque.

Did the movie win so many Oscars because it had merit, and the lack of editing was overlooked? Or did it win because it was sending a message to Putin? Or both? Messages are best when they are pithy. A quick and powerful jab. John Locke supposedly once apologized for an overlong essay, thusly: “I am now too lazy, or too busy to make it shorter.” Pith takes patience and time and effort.

If All Quiet is a message, Putin isn’t listening, but we are. We are captivated by suspense and a compelling story. But without good editing, we feel trapped, not knowing when our prison term will end. Please shorten our sentences, by editing yours! Editors might not be the most important people in the creative process or the first on the scene. But they can in the end make the difference between perfect and near perfect. Between creative freedom and a captive audience that needs bathroom breaks.

Word count and time limits should be our ruler, not our dictator, especially not a fascist dictator. But maybe we can take away something from the fascist Ezra Pound, about taking away what’s superfluous.

Renate Wildermuth is a freelance writer for The Albany Times Union, Adirondack Life Magazine and public radio. Her articles have appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle, The Miami Herald, and The Charlotte Observer. Her creative nonfiction has appeared in Syracuse University’s journal Stone Canoe. Her speculative fiction is forthcoming in the journal Mythulu. Her entry in the Galatea fan fiction contest took 2nd place.