Editor’s note: This interview is part of a series that will include an interview with Dow Mossman and a review of The Stones of Summer. A massively uncut version of the Mossman interview, which was conducted over the phone, is now available exclusively to Patreon supporters. Stay tuned for the review.

George Salis: Your classic documentary Stone Reader was recently remastered. What can you tell me about this process and the final results?

Mark Moskowitz: It was not fun. But I’m glad we did it. Robert Goodman took charge of the project. Thankfully. We’re going to get film nerdy here for a minute, but you’ll see why. I dug out the original 16mm A-B negative rolls from storage. That is what we used to do the 35mm optical blow-up to an interpositive, from which an interneg is made, from which answer prints are struck—what you see in the theater (or did back before digital projection). The film played worldwide, for almost a year, in theaters, on 35mm. It was probably one of the last documentaries, maybe the last, to screen that way in theaters. Completely shot and distributed on film. However, to remaster to digital required a lot of restoration. We could have just taken the 35mm interpositive and scanned it. But that had already been optically blown up and resized for 35mm. So we went back to the original small 16mm neg for the best clarity—supposedly. And it meant not just transferring and conforming and color-correcting the original negative, but also digitally repairing damage from splices, some moisture and dirt, and so on. Then the sound. We decided to use the stereo transfer from the DVD, rather than deal with all the old mag tracks or digital ones, but the DVD was slightly different than the film, not content-wise, but because the mastering involves different compromises. So that had to be re-sweetened and synced. And so on and so on and so on and so on. The benefit is twofold. We have both an HD and a 4K digital master now that can stream for years to come, and the film can be seen as it was originally intended, composition-wise. You see, 16mm is a 4×3 format, but the blow-up to 35mm turns it into 16×9 and therefore crops the frame top and bottom. The 4×3 version shows the film as it was originally formatted and conceived, and I like it that way.

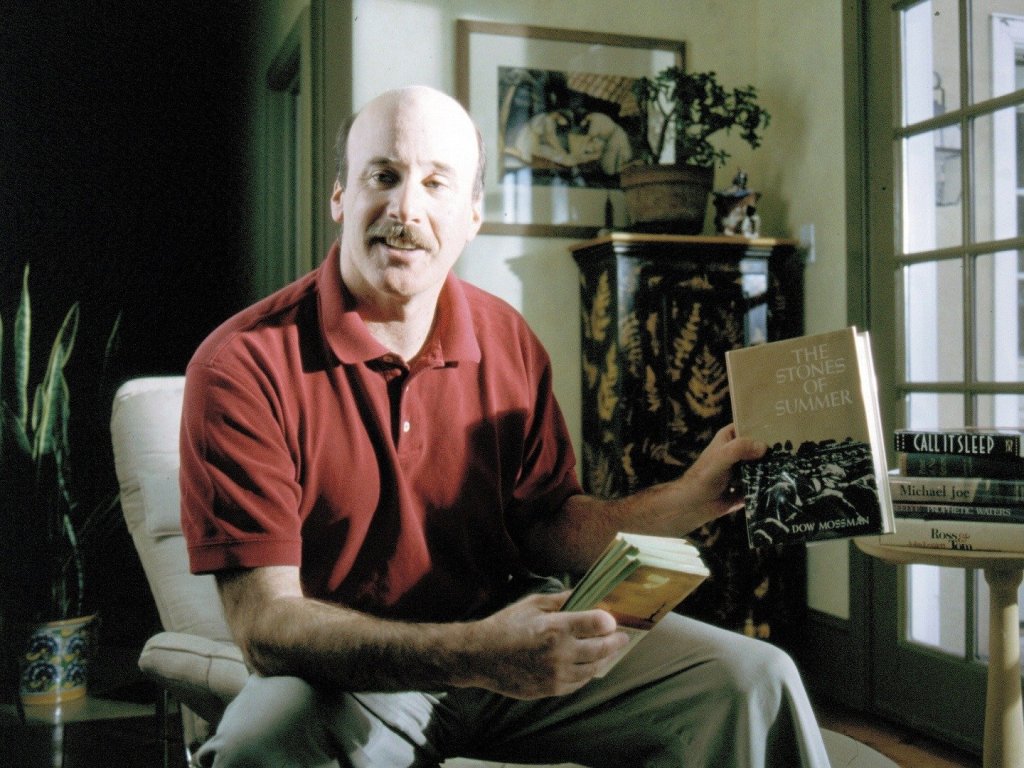

GS: Do you have a favorite passage or section from Dow Mossman’s The Stones of Summer?

MM: It’s been a long time since I last read it. But there are several that remain vivid. One from each section. In Part 1 there is a scene early evening, in the summer, at Dawes’ grandfather’s farm, after they return from the greyhounds. They come through the screen door of the kitchen and his parents and grandmother are there and conversation ensues. You know where everyone is, you can picture the kitchen, hear the screen door, the summer night alive with sounds. It’s wizardry. Hemingway does this with Islands in the Stream—by the way, a book Dow suggested I read—when they catch the fish, you know where everyone is on that boat, and if you go back and re-read it you don’t know how you know or how he did it. No mention is made of any of it. It’s all dialogue, character, and nuance, yet it is an action scene.

In Part 2, when Dawes is in high school, there is the great moment of the team’s guard, taking a shot from half-court and sinking it just to be an asshole. Just half a page but it climaxes the whole run-up of that section, turning the corner on all those school years, when you don’t care anymore.

In Part 3, the device of using Dan Guenther’s actual letters back from Vietnam pulls the whole book forward into the present, a present still real and here for many of us.

It is really a book where each part’s form fits function, the lyric coming-of-age perceptions of Part 1, the anecdotal episodic nature of Part 2 when we really grow up and save the stories of our lives, and Part 3, where the fragmented perceptions of adulthood are a way of revealing that nothing is as promised.

GS: What have you been reading and watching lately? Anything noteworthy?

MM: I liked Louis Menand’s The Free World. I sent it to Dow. Sort of a non-memoir of Menand trying to figure out how the culture got that way, takes root in the first place. The companion book is Gore Vidal’s Palimpsest, which I also enjoyed. Richard Holmes’s Sidetracks. Anything by him is worth reading. A couple science fiction books, one called House of Suns [by Alastair Reynolds]. I’ve been re-reading most of Bellow and all of Raymond Chandler. Both of their stories especially struck me this time around. There’s my love of mid-20th-century novels, what Vidal aptly calls the “gray” writers. This year I read The Man Who Knew Kennedy [by Vance Bourjaily], The Just and the Unjust [by James Gould Cozzens], and Thomas Harrow’s Women [by John P. Marquand],which was particularly good (Marquand’s late novels are a treat). Speaking of which, thirty years ago I was floored by Faulkner’s The Hamlet, The Town, The Mansion. Guess what, it’s even greater the second time around. More human, more funny, more immediate, more of everything once you’ve lived most of your adult life. And another trilogy, after two years of on-again-off-again-on-again reading, Robertson Davies’ Cornish Trilogy, some of the best engaging episodic fiction about the why of Art you can read.

Seen? I don’t see a lot. Some old cowboy movies that float in, I did watch most of Better Call Saul and finally watched Madmen a few years ago. There was Mary McCartney’s film on Abbey Road, took me back, and Jackson’s Let It Be, which if you’ve read Bob Spitz’s tremendous thousand-page book you can either skip it or enjoy it all the more. I’m open, so if there’s something you like, let me know….

GS: If you want some series recommendations, here are two of my favorites: HBO’s The Leftovers and Netflix’s Maniac. Speaking of watching, can you reflect on your favorite moments during the screenings of Stone Reader around the time it first came out in the early 2000s? How often was Dow able to attend?

MM: These were all good times, a phrase Jorma Kaukonen uses as a sign-off. I’m at the point where I get that now, but at the time it was a blur. Here are a few of many: 1) I’m standing in Fargo, ND. It is 3 below zero and the film is playing at the Fargo Theater. This must be winter 2004, after it has been in theatrical release for close to a year. I think, who the hell is going to come out on a weekday night in Fargo in 3 below to see this? It turns out, the whole town. Afterward, I learned if you live in a place with 2 feet of snow on the ground and minus 20 sometimes, something to do on a weekday night in only -3 seems like a fun idea. 2) Leslie Fiedler died the week the film opened at the Film Forum in 2003. All I could think about was what a gift it was for him to have given me a morning several years before, what an inspiring several hours, a true hero of mine. I remember standing in the lobby when someone came in and told me. And that’s mostly what I remember about the whole opening week. 3) When the film was struggling, Roger Ebert picked it for his 5th Ebertfest in 2003, a 3-day festival devoted to twelve films, four each day, old, new, forgotten, whatever, that he felt were never appreciated or widely seen. He picked Stone Reader for it, and Dow drove over from Iowa to Illinois. The film was seen in a 1,500-seat beautiful, restored old theater, like when I was young and saw movies that way. The house was full, it played wonderfully, with all the laughs and humor and pathos—something about more people in a theater brings out more humor in that film. Afterward, Roger talked with Dow on stage and learned Dow wrote one other published thing, an intro to a collection of film noir [Out of the Past: Adventures in Film Noir by Barry Gifford]. For the rest of the festival, film giants from Bertrand Taverner to Haskell Wexler to Ebert himself were consulting Dow about various film noir films and books. Good times. 4) The film was booked into Sacramento for a couple weeks and the distributor sent me there for publicity. It was a large duplex theater and the line was out the door. I thought, “Wow, he was right.” Instead, they were all going to see Russian Ark, and only 7 people, in this huge theater, were in line for Stone Reader. I invited everyone to sit together and we talked about books and movies as we watched the film together. Like an evening with old friends. Speaking of which, one I did not enjoy was when we opened in SF, on the heels of a sold-out Film Forum run, and we had momentum, and Dave Eggers hosted the screening, and on that day we went to war, the streets were filled with protesting, and no one could care less about the movies. I think there was a handful of us there, and the distributor pulled the film right after and we waited a couple months to re-release it after the war subsided a bit. Little did we know that war would continue through multiple presidents.

GS: There’s a moment in Stone Reader when you’re replaced with your “younger self,” as it were. I was reminded of that moment while watching Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, in which a character criticizes the protagonist for including in his documentary a scene where he chats with Hernán Cortés. Can you talk about the bending of truth in the service of storytelling, particularly within the documentary genre?

MM: Are you referring to the scene of my son reading The Thin Red Line [by James Jones]? Let me go back a bit. If you make a nonfiction film, or any sort of film, what matters is what you feel or think at the end of it or during the weeks after you see it. It is one punch, even though it seems like a lot of scenes or jokes or facts or conflicts. Kubrick’s films are like this. They may drag at points or seem redundant at others or be enigmatic at times, but you think about them well after you’ve seen them. The truth is somewhere in that moment or those weeks, months, years of reflection. To that end, the devices you use to tell the story or convey your point of view, or the information at large, are subservient to getting it across. If you want third-party journalism—which is a branch of nonfiction where someone condenses and uses facts to report on something outside of their area of expertise or takes the most expedient, declarative look at a situation or event, then an examination of those facts is important. I’m not much interested in journalism, and rarely read or watch it; to me, it’s a moving target. I’d rather the target be stationary and feel myself moving around it. For years Herzog and Burns have danced around this question. And never the twain shall meet. I’m on Herzog’s side. What you experience at the end is what matters, not an examination of the details along the way. Then, of course, there’s Norman Mailer’s take on it all. He refuses to make a distinction between fiction and nonfiction. He says simply that it is all just narrative and some kinds have more details than others.

Stone Reader, to take it a step further, is a story told almost like a fable. It has a fable-like, dream-like construction, yet everything that happened in it is real and happened as you see it. It’s up to the director to put both of those notions across to make it work. The structure is imposed on the events. The way the story is told is the story. It is both like engaging with someone you have not seen in many years and trying to keep their attention as you tell them this thing that happened to you. But it is also a film born of literary construction. That is, most fiction stories—take Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”—wouldn’t be stories at all, just newspaper items, if it wasn’t for the way the story is told. They would be one paragraph or even one sentence, “Old woman found dead in her home, nothing taken.” Wilted roses wouldn’t even be mentioned.

GS: What would you have done had you never found Dow Mossman or if you discovered he had died? Would you have been deeply unsatisfied or would you have gotten all you needed from the thrill of the hunt, as it were, or perhaps a mix of both? I’m now thinking of the final line from the film Millennium Actress: “After all, what I really love is the pursuit of him.”

MM: That’s important. Pursuit, or as one gets older, simply purpose. My father, an avid golfer, used to say “As you walk down the fairway of life you only have one chance to smell the roses.” I always had a hard time with that. My goal was completion of things, not enjoying the process of getting there, and these films I’ve made are that, enjoying the process of getting there. When I finished the 10-part series It Was the Music, I had countless questions about the economics of it. And my answer was, at this point in my life, it was as if I always wanted to sail around the world, and now I could, with a hand-picked crew, stop at ports and meet wonderful people and hear stories about far-off places, and years later when I returned (film finished and distributed) it was time to sell the boat for what I could get. It wasn’t about making money, trading, or doing business as I went, it was about a trip, and it cost something, a lot, and the money I got back was something incidental to the experience. Does that make sense?

But to answer: I was pretty certain Dow was gone, or in Hawaii or somewhere, and in pre-internet search days unfindable really. And I didn’t really care. It wasn’t about that. In fact, the scene in Maine with John Seelye was originally the back 1/3 of the film and ended with us calling a number someone had found for Dow (it turned out not to be) and we couldn’t get a signal on the cell out at the far eastern end of the country in Eastport, a scene I cut. Even though I thought that was the perfect ending. Because, as I say in the film, I got obsessed.

GS: Can you talk about some of your favorite documentaries? What about literary documentaries in particular?

MM: I don’t see too many. When I made Stone Reader, I doubt I had seen five documentaries in my life. Roger and Me. Sherman’s March which I never got to the end of, although later I saw Ross’s film Bright Leaves and found it brilliant because it happened in-scene. As opposed to told. I have never been able to see Ken Burns-style films because they remind me of the stuff I make for clients, where you use authentic and validated footage to mask the audio track where you can claim and say anything and it seems genuine because the footage is credible. I have a hard time with interview and B-roll shows where they sit people down and they sequentially tell the story and random footage gets cut on top of them. These are like the dozens and dozens, actually hundreds of corporate films I made for years.

After Stone Reader, I became more cognizant. I liked a couple Agnes Varda films. Beautifully done and subtle. I like most of the Herzog things. And I’ve liked some of the films in the Stone Reader “tradition,” like Winnebago Man, which actually seems like a satire, and the film about Ginger Baker. Barbara Kopple’s films I like. I have a lot of respect for her and the way she and Tom made all those films. Gimme Shelter is an important film as well. The Maysles were inventive.

You know, a lot of nonfiction film, if it is not a social justice film or historical narrative, is about biography. And it’s important to me to know who is making it. Otherwise, I have a hard time trusting it. Ever since Boswell, it’s not uncommon for the writer to share her or his passion for the subject. And I think that works in film too, as opposed to these films that are nameless, faceless, seemingly objective “content.”

About the movies in general let me say this: It was a mid-20th-century format. I saw The Longest Day, The Nutty Professor, The Dirty Dozen, Last Tango in Paris, and The Deer Hunter all in large single theaters on very large screens. Annie Hall I saw on the first “small” tunnel theater screen in Philadelphia. And as much as I like and admire the movie, I felt the difference. Yet it amazes me how many times I can see films I’ve seen both ways, like The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, or Wyler’s The Big Country on TV screens, even small TV screens, and still see something new and still find them appealing despite having seen them large first.

Have you seen other documentaries or series that have inspired your own writing or thinking process, or led you to step back and rethink some things?

GS: I don’t watch documentaries too often, partly because I’m never “in the mood” for them even though I enjoy them once they’re playing (yours quickly shot to the top of my list of favorites). As such, I haven’t seen very many literary documentaries other than yours and somewhat recently The Booksellers, which was pretty good, particularly the first two-thirds. But I’m certainly a fan of Herzog. His Cave of Forgotten Dreams gave me a dose of inspiration as I worked on a section in my second novel that’s set in the Neolithic period. And then there’s Grizzly Man and Into the Inferno. All wonderful. Even Pumping Iron was enjoyable. I’ve been meaning to watch Marjoe for a long time now. As for my next questions: The following is in the back of the Barnes & Noble Books reprint of The Stones of Summer: “This edition of The Stones of Summer is published in association with the Lost Books Club, Inc., a not-for-profit corporation dedicated to introducing, preserving, and passing on to future generations hard-to-find, out-of-print, or otherwise forgotten works.” What can you tell me about this venture and is it still going on? I’d love to know the books that were republished or were in the pipeline. These are the titles I could track down online: Heckletooth 3 by David Shetzline, The Furies by Janet Hobhouse, Silk and Cyanide by Leo Marks, Barefoot in Babylon by Robert Spitz, and The LBJ Brigade by William Wilson.

MM: Well, this is something I was very keen on when I started it but the explosion of the internet has made it unimportant, I think. Steve Riggio, who was CEO at Barnes & Noble at the time Stone Reader came out and was instrumental in all that followed (he loved the book and asked his staff one question: “What can we do to help this writer?”), reprinted The Stones of Summer with a generous royalty. We took a percentage of that and put it toward a 501c3 to put out more “lost books.” Hundreds of suggestions flowed in, and I bought used copies of them, and have them all in a rack upstairs, and have read about thirty over the years. Around the same time, the NYRB started their series, as did others, and so we collaborated on Janet Hobhouse’s The Furies. Some of the others I would like to do; I still may, but now that it’s easy to find old copies online and so many are print-on-demand or find their way to digital formats, I’m not sure the need is there. And as far as trumpeting them, all the book sites and YouTube sites, and so on, have taken that over in spades.

GS: What are some other writers you would track down if you had a chance? Why?

MM: I tried to track down Milan Kundera in the 1990s, and had a number of nice faxes back from his wife, Vera. I had planned a trip to Paris to film him but life intervened. Javier Marías I would have liked to meet. Too late now. John A. Williams I did meet toward the end of his life, and that was exceptional, inspiring, and meaningful. Since I read very little stuff after about 1980 or so, there’s not a lot of people I can think of who are left. Dave Eggers, as mentioned, I have met, but if I hadn’t, I might list him. Richard Holmes I would love to meet; he’s elderly now. How about you? What writers would you like to sit around with, and for what reason? Hey, is Janet Malcolm still alive? [She passed away on June 16, 2021.] Jim Harrison, there’s one. Pynchon, why not.

GS: I went on two literary pilgrimages last year to meet two of my all-time favorite writers, which allowed me to enjoy and relate to your documentary that much more. I went to visit Joseph McElroy in New York in June. He showed me around his place, took me to lunch, then we went for a walk by the Hudson River. It was a significant meeting for many reasons which I’ll be writing about in an epic essay I have planned. Memories I’ll cherish for a lifetime. Simply put, Joe is as wise as he is kind. And, in Stone Reader, I was delighted to see you holding a copy of his Ancient History, and you asked John Seelye, “Have you heard of Joseph McElroy?” and he of course said, “No.” He has a cult following but is sorely, sorely underappreciated. Then in October, I visited Alexander Theroux at his home in Cape Cod. He and his wife were very kind and hospitable. We ended up talking for two and a half hours about many different topics, including his meetings with Jorge Luis Borges, his thoughts on Infinite Jest and his correspondence with David Foster Wallace, his time as a Trappist monk, his twin daughters, what he’s currently writing, regret, The Leftovers, and much more. He also loves the idea for my third novel, although I’m still trying to finish my second. I’ve been working on it for the past seven or so years and will finally finish this year.

I agree with you about a potential pilgrimage to see Pynchon. He’s the big fish for being so reclusive. I wanted to visit John Barth but unfortunately learned that he’s had dementia for years and has been in a mental twilight. If I had to pick only one author, then it’d probably be Don DeLillo. I’d say Salman Rushdie but I was lucky enough to meet him at an event in 2015, although I’d love to spend more time with him than one gets in a book signing line. Anyway, what can you tell me about your upcoming film projects?

MM: There are several. I don’t work on one thing at a time. But then one thing takes off and I concentrate on that. Right now I’m editing a film called Art Stops Here, which I began even before I finished Stone Reader 20 years ago. It’s the final volume in what I jokingly refer to as the 20th-Century Trilogy (along with Stone Reader and It Was the Music), because I seem sort of stuck there, even though all the films were shot in the 21st—well, Stone Reader just at the turn. There’s also a feature-length cut of It Was the Music that will get out there—somewhere—different in ways than the 10-part series.

GS: Have you tried writing any of your own fiction?

MM: Tried. When I was young I got a nice personal rejection from Roger Angell at The New Yorker. I didn’t know that was encouragement. I wrote novels I never sent to anyone, they’re all here. Then when Robert Downs (in Stone Reader) showed me all the novels he had in a drawer that were never published I didn’t feel so bad. The time comes when you have something urgent to say and that is the best motivator for doing something well and finishing it as opposed to just doing something.

[After giving Mark an overview of my almost-finished second novel, Morphological Echoes, he wrote the following:]

I like your admiration of, and inspiration from, Big Books. In my youth, those were Giles-Goat Boy, V., The Recognitions, Stand on Zanzibar, The Alexandria Quartet, The Worm Ouroboros, From Here to Eternity, and for some, Sometimes a Great Notion. Books that said to a young person you can do anything and everything. Later in life, I gravitated to big books which may have been narrower in focus but deeper in presentation, and in some ways more substantial. Over the last ten years, I’ve re-read a lot of those early big books. Some, like The Worm Ouroboros, From Here to Eternity, I found even greater. Some, like The Alexandria Quartet, I found equally appealing but for different reasons. Still others, Stand on Zanzibar and Sometimes a Great Notion, I couldn’t read again. But for the most part, the big books I read while young have just as much power now that I’m old, only it’s different. I read V. three times before I was 30. 17, 19, and 29. I’ve thought of reading it again, but I’ve had trouble with Pynchon in later years and don’t want to risk it.

Your massive undertaking intrigues me. There seems to be a resurgence of writers going after the Big Book, and readers gravitating to them. Even so, most of the great narrative tricks were realized long ago. Don Quixote, Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, Tristram Shandy, Persuasion, Sentimental Education, Candide, The Woman in White, Moby Dick, Dostoevsky’s The Devils. In my generation, they were reinforced by Vonnegut, Barth, Bellow, Hawkes, and Brautigan, the latter the greatest example of somebody just doing it his way. Talk about Big Books, one of the best you can read is William Hjortsberg’s 1,000-page bio of Brautigan [Jubilee Hitchhiker], done with a novelist’s brio. Try Hjorstberg’s early books if you like McElroy. I read all the McElroys through Lookout Cartridge and loved them, but the rest remained shelved, although I did make it a few hundred pages into Women and Men.

One has to be careful not to try and put the whole world into one work. Depending on one’s stamina and patience, it is hard not to fall into that. One has to have great respect for the self-discipline of an early generation: Bellow, Roth, and even DeLillo who were (are) able to pare down one’s work as time runs out.

Keep at it. It all matters.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Mark Moskowitz is known for his issue-oriented media, including more than three thousand political spots for hundreds of races nationally and worldwide. He has been awarded “Pollies,” political media’s highest award, for five consecutive years. Newsweek described his media as “brilliantly targeted,” and CNN called it “a model of the medium.” For over forty years he’s specialized in telling reality stories by bringing amateurs to life on camera.

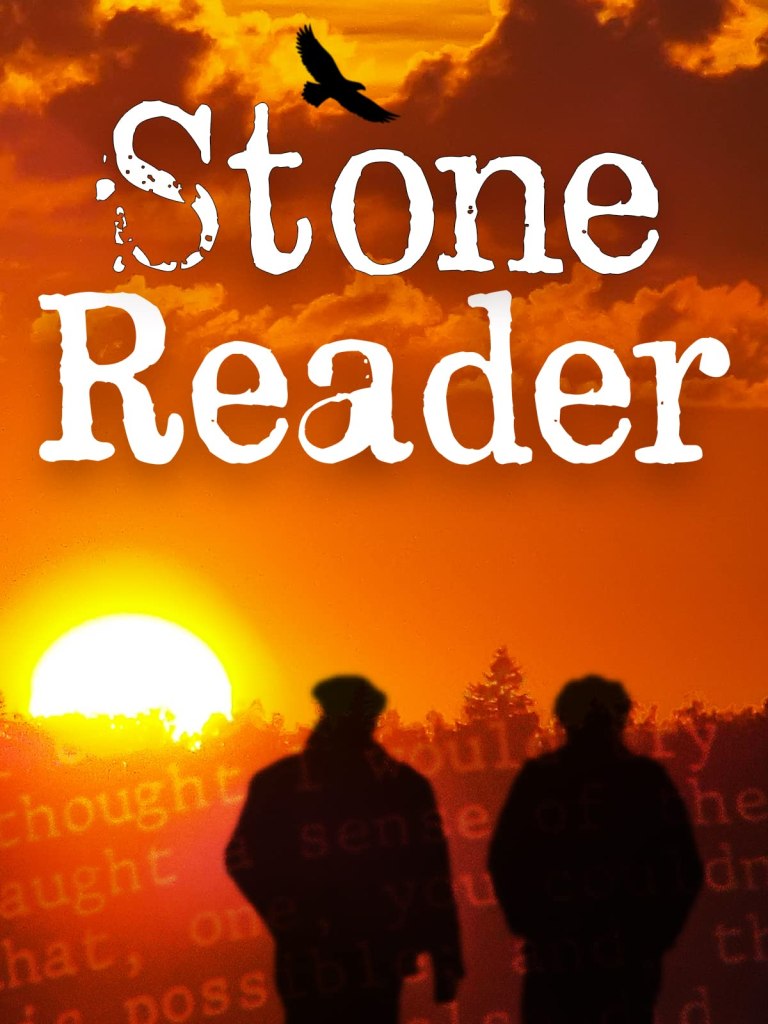

Stone Reader, his first feature film, won the Audience Award for Best Feature Film (a first for a nonfiction narrative) and a Special Grand Jury Honor (the festival’s top prize) at the 2002 Slamdance Festival. The International Documentary Association (IDA) nominated Stone Reader for its Distinguished Achievement Award in the Feature category. IDA is the largest association of nonfiction filmmakers in the world and an IDA nomination is one of the most prestigious honors a nonfiction film can receive.

His latest film is It Was the Music, a 10-part series.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.