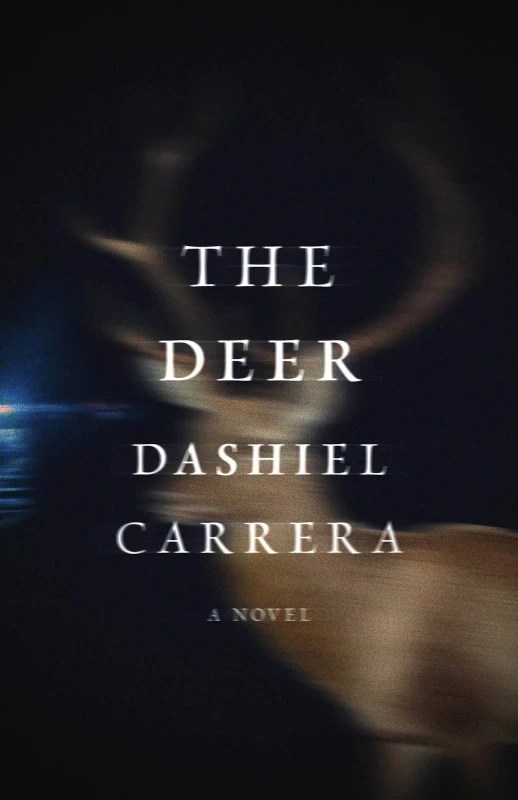

A lightbulb flickers in the corner of your vision, or perhaps reflects off a surface of smooth glass and illuminates what’s inside. And often, these instances will not bring about anything but the mere perception of light—the change in whatever they may shine upon. Until a random day somewhere in the future, when things line up, that light brings about memory—not déjà vu necessarily, but the symbol of light as a metaphorical image which you cannot help but associate with some thought or event, some death or pain that long ago was so stark in your mind, and is now just associated with a mental data point waiting to be reopened. Dashiel Carrera’s debut novel, The Deer (Dalkey Archive, 2022), explores the absurdity and simultaneous beauty of memory, of how every point in time references the past and the future through images, symbols, words, and motifs, and how our reluctance to allow these connections to flow freely in our mind may hinder any capacity we have to understand or to heal.

The Deer begins with the simple moment of a man, Henry Haverford, crashing his car after hitting a deer late at night. At first, the reader understands that the deer exists or existed despite Henry insisting it did not. Although, as the novel progresses, our belief in the deer, along with numerous other facts and fictions about Henry’s life, somehow begin both to gain an air of mystery and become clearer; the reader ceases questioning Henry’s sanity and begins to see the connections. In his past, there was the death of a dog—blame that was thrown about, showing itself to be meaningless in the face of sorrow. Or had it been the death of his mother that reflected in the light of the deer’s eyes? The blame now transferred from the dog’s death to the mother’s, the sorrow perhaps transferred as well. Or maybe memory merely served as the connection between the two—sorrow for one never existing and simply being the fusion of events to allow him to better comprehend the place of the other in his life. These places of sorrow lie on top of one another in time, not separate. His and our life are built on infinite moments replayed behind our conscious minds. And it’s not just our lives that form our memory, but the lives of others as well.

When Side B—Part Two—begins, Henry’s life no longer seems his own. He becomes a slave to these subconscious visions, seeing himself over his mother’s bed, sometimes not even as himself. Henry becomes the deer, sees through the eyes of his sister, and becomes a single entity through the intertwining of two, only to be forced out of this chimera shortly after. Stories told to him imprint images in his mind that may be the cause of the deer’s eye drawing such pandemonium out of a simple event. Because no moment, no spoken or written word exists in our life or lives past that does not have influence and inject meaning into the events surrounding us daily. It is why, as Carrera argues, these connections must be allowed to flow freely so we can comprehend our lives, our emotions, and our histories.

The novel flows beautifully if not for one mistake nearing the end. In the last few pages, Carrera seems to lose trust in the reader, assuming they can’t decipher his message for themselves, and spells it out on the page in italics. Luckily, the explanation holds its own aesthetic and abstraction, allowing for multiple interpretations, but it is an explanation nonetheless. The fault in this lies in three possibilities: the reader was grasping the message or nearly grasping it, and the joy of this finding is then ripped away; the reader did not grasp the meaning only to have it explained to them, removing any need for further critical thought or rereading; the reader grasped another meaning which was then invalidated. It takes the numerous interpretations that can be gleaned from a novel of this complexity and narrows it down to one—or, at least, takes away some of the fun in the search. Though it is quite a mistake, there is not much use in harping on a single page in a larger work. Look past it, forget it even, because there is immense beauty in all the words surrounding it.

On the back cover of the novel, it states that the work is “part jazz record,” which initially elicited a chuckle and an eyeroll. Although, as the novel began to reveal its themes and ideas, it became clear that there is no other way to describe it. Imagine true jazz: the unplayed notes of Thelonious Monk or the chaos of Coltrane’s Interstellar Space. The former evokes meaning with silence, where a blank space between sounds will gain meaning through the rest of the song, through new iterative versions of it, or through the knowledge of what could exist—two or more notes coming in to fill the void, but never in the time that the void existed. Instead, they occur in the future, meant to be placed back in that void, though never heard as a part of it. The latter shows the chaos of modern life through successive notes that seemingly have no musical connection with each other, yet patterns and familiarities begin to emerge within the structure, making more sense of what came before, though never entirely clearing that mind fog. Those extra pieces give the familiar meaning—insanity around the melody. These ideas of jazz are what Dashiel Carrera achieves in The Deer. It is not that he merged mediums but that he created a connection, a light in a place of void, between styles of art that are seldom bound. It is a brief but profound and beautifully written novel which, despite its flaws, also achieves something that many contemporary novelists do not even strive for, let alone succeed in: it has style—true style—and is not afraid to seek something new.

Andrew Hermanski is currently a high school English teacher. He has received his Master’s in public health and his B.S. in psychology from the University of Arizona. Although his formal educational background is in the sciences, his love for literature and teaching has led him to pursue a different career path. His focus in literature lies in postmodernist and experimental fiction. In his free time, he also loves to watch movies, cook, write fiction and book reviews, and play video games (and, of course, spend time with his partner and his cats). Find him on Goodreads and Twitter (@OedipasKvass).