Editor’s note from George Salis: Jorge Luis Borges’ writing is so singular that it begat the description: Borgesian. Until now, I’ve only had the honor of brushing shoulders with Borges’ spirit by interviewing authors who knew or met with him at least once, including Luisa Valenzuela, Abel Posse, and Alexander Theroux. I’ve also published an interview with Borges translator Suzanne Jill Levine. I’ve even published a story by Garrett Rowlan titled “Biblioteca of Babel,” which features Borges as a fictional character. Now, it’s with pleasure that I present a reprint of an interview with the legendary writer Jorge Luis Borges, conducted by Clark M. Zlotchew.

The following interview took place in Borges’s apartment in Buenos Aires on July 16, 1984; carried out in Spanish, it appears here in the interviewer’s translation. It is the first conversation in the collection of interviews with eleven writers of Spanish language literature in Clark Zlotchew’s Voices of the River Plate: Interviews with Writers of Argentina and Uruguay (First Edition, Borgo Press, 1995 and Second Edition, iUniverse, An Authors Guild Backinprint.com Edition, 2011). A small segment of this interview, untranslated, appeared in Hispania, in March 1986. The complete translation into English first appeared as ”Jorge Luis Borges: An Interview by Clark M. Zlotchew,” in The American Poetry Review, Sept./Oct. 1988, Vol. 17, No. 5.

Prologue

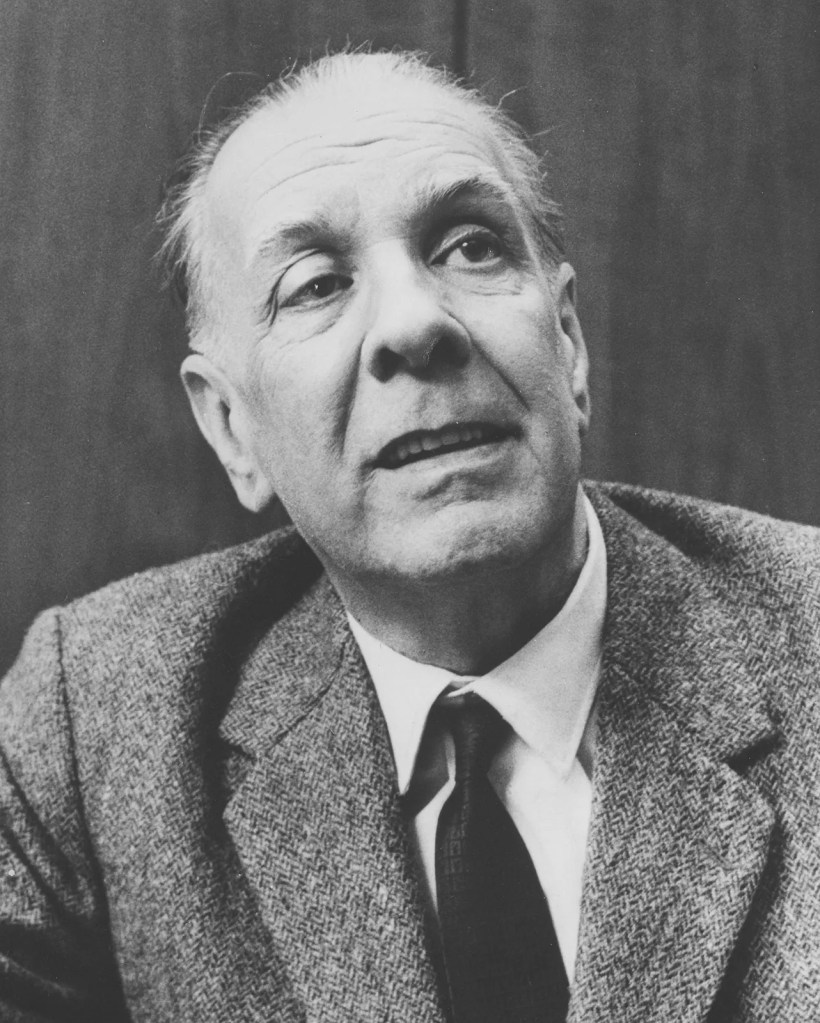

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) is considered by many critics and writers to be one of the greatest authors of fantasy and magical realism. The major critics of world literature became aware of his highly speculative work in the 1960s. By the 1970s, Borges had become the most eminent Latin-American writer of the twentieth century. Until the day he died in Geneva, it is safe to say he was the best-known, most admired, and most widely translated living author who wrote in the Spanish language. His poetry, essays, and, most of all, his short fiction are among the most important pieces of modern world literature. Very few authors have been as widely praised. Very few have been as widely attacked. Very few have been as widely loved or as widely abhorred. Certainly, very few have been discussed and even argued over as he has.

While superficially Borges’ style appears realistic, most of his themes involve philosophical and metaphysical speculation. His writings are marked by the almost obsessive view of the universe as a labyrinth too complex for mortals to comprehend, the divergence between appearance and truth, between objective and subjective reality, history as a cycle, the problems of matter, chaos, human identity, and individual personality (all men are one man, one man contains all men), time and the infinite. As he points out in the following interview, Borges creates literature out of literature.

Many of Borges’ techniques—internal duplication (stories within stories), contrast between clock time and human time, portrayal of human beings as the pawns of a higher power—are designed to destroy the bonds between the real world of the reader and the fictional world created by Borges. As John Updike said (The New Yorker, 10-30-65), Borges’ fictions “answer to a deep need in contemporary literary art: the need to confess the fact of artifice.”

—Clark M. Zlotchew

Clark M. Zlotchew: What happened to you a long time ago on the Uruguay/Brazil border, in Sant’Ana do Livramento?

Jorge Luis Borges: It was the time I saw a man killed, the only time in my life I saw a man killed. It didn’t impress me at the time; it impressed me later. The thing grew larger in my memory. Imagine: seeing a man killed.

CMZ: Did you actually see it?

Borges: Well, maybe I didn’t. (laughter) We are liars.

CMZ: No, no. I didn’t mean to imply…I just wanted to know if you were close enough to see it with your own eyes, or if you were only in the same room, or close, when it happened.

Borges: I think so. In any event, that morning. It was in a bar, just a few feet away. And there was this black man who was the bodyguard of the Governor’s son. And this cattle drover came in, an Uruguayan…I think he was drunk, really drunk. He had no reason to kill him, but he killed him. He fired twice.

CMZ: I hadn’t ever heard those details before.

Borges: Well, that’s because time passes and I’ve embellished it so that I wouldn’t be boring. (laughter)

CMZ: And the other people….

Borges: Well, the other people have luckily all died and cannot contradict me. They were Enrique Amorim, who was married to a cousin of mine, and Marquez Miranda, an archeologist. An archeologist in the Argentine Republic has absolutely nothing to investigate. Well, it’s an easy job, isn’t it?

CMZ: Has that experience influenced your fiction?

Borges: I would have to think so. That and what I’ve read. I believe it was Emerson who said, “Poetry springs from poetry” or “Poetry is born of poetry.” I don’t remember exactly. Reading is very important. And Alonso Quixano, who became Don Quixote, knew something about that. Because if one reads Don Quixote, the only thing that happened to him was that he read Amadis of Gaul, Tirant lo Blanc, Palmetin of England, and other “books of chivalry,” about knights in shining armor….

CMZ: The comic books of the time.

Borges: Right. Of course.

CMZ: I have another question that—

Borges: Only one?

CMZ: Well, one at a time. Last year I read in an Argentine newspaper that you mentioned you had once been in love with Cecilia Ingenieros…. [dancer and choreographer, daughter of José Ingenieros, an Argentine physician, pharmacist, positivist philosopher, and essayist.]

Borges: Yes, that’s true.

CMZ: But the reporter didn’t pursue it. Would you like to talk about that?

Borges: Well, she just became bored and left me. And with good reason, I’m sure. I haven’t seen her for a long time. I mean now…now she’s married, she has her children. Why not say that at one time we were sweethearts, why not? And that I remember her with great affection. I think it’s all right to say this, isn’t it? The better man won. Yes, I can say it now, but at that time, no. She broke off the relationship in a very honorable way. She asked me to meet her at a tearoom that’s on Maipú and Córdoba [the St. James]. I hadn’t spoken to her for some time and I thought. “How strange that she called me,” and I was feeling very happy and then she said to me, “I want to tell you something you’re going to hear anyway, but I want you to hear it first from my lips: I’ve become engaged and I’m going to be married.” So I congratulated her, and that was that. A charming woman. She had been a student of…she could have been a dancer with Martha Graham, an American. Well, she studied under Martha Graham in New York for a year. I think it was in the Village. Well, let’s be indiscreet and talk about this. Bygones.

CMZ: You’ve said that Greta Garbo had a certain something that was very attractive. Exactly what was it about Greta Garbo that was so attractive?

Borges: Ah, Greta Garbo: the only person in the world, Greta Garbo. Unique. I was in love with Katherine Hepburn too, and with an actress who has been forgotten, Miriam Hopkins. We all were in love with her, all those in my generation. She was really beautiful. And with Evelyn Brent, who worked with George Bancroft, “Prince of Gangsters.” And in Dragnet, Showdown, etc. We were all in love with Miriam Hopkins, with Greta Garbo, with Katherine Hepburn, and a few others.

CMZ: The BBC made a film about your life…

Borges: It was very good. Very good. Here [in Argentina] they wouldn’t have…I wasn’t well-liked. It couldn’t have been made here. But the film was made in Paris in the hotel “L’Hôtel,” which is the hotel that used to be called the Hôtel D’Alsace, in which Oscar Wilde died in the last year of the last century. In 1900. I was going to say it was one year earlier, 1899, but it was in 1900. Part of it was filmed in the basement—very strange—the circular basement of the hotel. It was a cylinder, quite large, and the walls were lined with mirrors. So, in some way or other, the basement was infinite. And later it was filmed on some ranch in Uruguay, near the town of Colonia, with Uruguayan actors, with other scenes in Montevideo, on that huge hill across from the city itself, Montevideo Heights. The film is the story of my life and I took part in it. Maria Kodama appears in it too. And there are several scenes taken from my short stories. For example, in the movie I speak with a boy of twelve or thirteen who wears glasses—he represents my childhood, and this scene comes from my short story, “The Other”—and then I converse with an even younger child, like in my story. Well, it’s a very serious film, a very good film.

CMZ: Can this film be seen?

Borges: You mean here in Buenos Aires?

CMZ: Anywhere.

Borges: Probably. Maybe at the Municipality you can check it. There was this Mr. David…I don’t remember the last name. Well, anyway.

CMZ: At various times, you’ve shown some antipathy to the central region of Spain, to Castile. Why?

Borges: Well, yes, Castile specifically, not Spain in general. I’m not talking about Galicia, about Catalonia, about Andalusia, which are admirable lands—almost countries—but Castile. In general, the average Spaniard is a good man, the best in the world, ethically, but Spanish literature has not impressed me particularly, with certain exceptions: Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Fray Luis de León. But Castile…Castile is where those conquistadores came from, as well as all those military men, idiotic military men, fanatic Catholics, all of whom have put their mark on our countries [Hispanic America]. Militarism, fanaticism in religion, intransigence…all from Castile. It’s the source of all our militarism, dictatorships….

CMZ: Speaking of militarism, when the military junta overthrew Perón’s widow and took over the Government of Argentina in 1976, you were glad….

Borges: Well, yes. But, how was I to know what they were going to do later before they did it? And even afterward…we didn’t know about the disappearances, torture, murder here because there was total censorship. But, yes, I was mistaken.

CMZ: The Chilean dictator, General Pinochet, presented you with a decoration….

Borges: No, no, no. There was no decoration. I had gone to the University of Chile where I was awarded the title of doctor honoris causa, and while I was in Santiago to receive that honorary doctorate, the President invited me to come for dinner. Nothing more than to come for dinner. And, well, since I was there in Santiago, I couldn’t refuse, could I?

CMZ: Is Anarchism a viable form of society?

Borges: I think we’d have to wait some two hundred years—a very short time, right?—of having no government, having no police force, of being a kind of people different from what we are now. But for the moment—this is not the Soviet Union—government is a necessary evil. And now, I think that in this country we have a certain right to hope, nothing more than to hope. But, I believe that after five years or so…well, after a long convalescence, shall we say, after so many evils…Peronism, terrorism, the military junta, the ones referred to as the “disappeared,” kidnappings, torture, death, and then…. This “shortens the meaning of this world,” doesn’t it? But, I hope and expect that…. Anyway, it’s a real joy to have Alfonsín [as President], even though I’m not a member of the Radical Party [of Alfonsín].

CMZ: Might there be any mutual influences between your early poetry and the tango lyrics that appear in the same era?

Borges: Let’s hope not, eh? Because they’re so bad. (laughter) I don’t think so, not the tango. The milonga, yes. I have written a book of milonga lyrics. The milonga is of the people; the tango never was. You know, the instruments used in the tango were the piano, the flute, and the violin. If the tango were of the people, the instrument would have been the guitar, as it is in the milonga. Speaking of the guitar, let’s get into etymological territory a bit. The origin of the word guitar is the word zyther. It’s almost the same word. Whether you say [in Spanish] guitarra or citara, the vowels are exactly the same, aren’t they? It seems that string instruments were invented somewhere in Central Asia, and from these string instruments developed the harp, the violin, the zyther, the guitar. But, the guitar has its origins in the word zyther, that is, kithara in Greek. Just a little etymological curiosity for you. And you, where are you from?

CMZ: I was born in New Jersey, but I teach in the state of New York, near Buffalo.

Borges: I’m acquainted with Buffalo. I’ve been to Niagara Falls. And New Jersey, it’s the West Side of New York City, isn’t it?

CMZ: It’s west of the city of New York, across the Hudson River.

Borges: Ah, yes, of course. The Hudson…. You know, Mississippi means ‘Father of Waters,’ something like our great waterfalls, Iguazú, which means ‘The Big Water.’

CMZ: Well, to get back to the tango and the milonga: apart from the musical instruments, what is the difference in the music itself between the tango and the milonga?

Borges: The milonga is a kind of brave, wild music. It’s a merry music, while the tango is a very sentimental, “respectable” (in the worst sense of the word) music. Yes, and the milonga [Borges means to say tango] was never the music of the people. One proof of this is that they never danced the tango in the tenement buildings here. And the tenements were where you could find the representative people of Buenos Aires. They never danced the tango there. Milonga, yes; tangos, no. No, the tango would be the music of the bawdy house, of the brothel. And the people rejected it, naturally. But I’ve seen it danced by men dancing together. Because no woman would be seen dancing the tango, since it was a dance associated with prostitution. But the two dances [tango and milonga] are of African origin. Even the sounds of the names are African: milonga, tango, aren’t they? All that ango, onga, ongo, as in Congo.

CMZ: Your short story, “The Intruder”: Why have you said you consider it the best story you’ve written?

Borges: No, I don’t think so. And listen, I want to tell you to…to avoid a frightful film that’s been made of it. Now, they’ve injected into the story two elements which were not in my story, which have nothing at all to do with me. These elements are: incest and homosexuality. Oh, yes. And sodomy. Well now, this gentleman [the director], [Carlos Hugo] Christensen, I think his name is, an unworthy descendant of his Viking ancestors, has introduced homosexuality, incest, and sodomy into my story. And ridiculous scenes…. For example, in my story I say that these two brothers share the same woman, but it’s understood that I meant successively, not simultaneously. But Christensen has this scene for comic effect in which there is an actress standing there, undressed, and then one gentleman advances toward her from the left, while another one advances from the right, and they perform a pretty uncomfortable form of coitus, I’d say. But this is done, I imagine, for comic effect.

CMZ: You really think it’s for comic effect?

Borges: I suppose so. If not, what kind of effect could it have? Two gentlemen who are naked, a naked lady, and these gentlemen advancing from both sides…. It’s madness. And it’s not my story. It’s something they’ve added. But what makes me angry is that what it says is “The Intruder, by Jorge Luis Borges.” Look, if you were to tell me, “I’m going to respect the original text,” I would say, “No, a film is not going to respect the text. The text is just a point of departure for a film. If you want…do whatever you wish with the film, but if a great many new things occur to you, don’t mention my name. Change the title.” But there it is with the title of my story, and with my name. And with incest, homosexuality, and sodomy. Charming.

CMZ: What do you remember of Rafael Cansinos-Assens?

Borges: As far as I am concerned, he is one of the people who have impressed me most in my life. I don’t know if, simply by reading his books, you would feel the same way. But conversation with him is an extraordinary experience. That man once said, for example…instead of saying, “I’m acquainted with…I know fourteen languages,” he said, “I am able to salute the stars in fourteen languages, classical and modern.” He translated an entire work of Galsworthy’s and he translated part of De Quincey. Then he translated the novel L’Affaire by Henri Barbusse, as well as others from French. And then he made a direct translation of the book The Thousand and One Nights from Arabic. He was of Jewish origin, as I am, and he made an anthology of the Talmud. And then he had translated from the Greek the work of Julian the Apostate. And he knew Latin. And the first time I met him, we spoke all night long of Thomas De Quincey. Cansinos-Assens had been born in Seville but was living in Madrid. He wrote a very beautiful poem about the sea, and I congratulated him on it. “Yes,” he said, “it’s a beautiful poem on the sea. I hope to have a look at the sea some day.” He had never laid eyes on the sea!

CMZ: You just mentioned that you are of Jewish origin, and I’ve seen you refer to the fact that your mother’s maiden name, Acevedo, is a Portuguese-Jewish name. How do you know this?

Borges: Well, it’s curious. You know, one day Cansinos-Assens came across his family name while looking through the archives of the Inquisition. He found the name Cansinos, that is. And from that time on, he decided he was a Jew, descended from those forcibly converted to Catholicism. All this led him to the study of Hebrew. And he wrote a book of what might be called erotic psalms called El candelabro de los siete brazos (The Seven-Branched Candelabrum) referring, of course, to the menorah. Well, anyway, in my case, there is a very good book called Rosas y su tiempo (Rosas and His Times).* And in that book there is a list of family names referring to the Buenos Aires of the period. And they were Portuguese Jews. Well, I believe the first one is Ocampo. And that’s why some people in Buenos Aires high society refer to Victoria Ocampo as a “Jewish upstart”** (laughter), right? Well, these Portuguese-Jewish families had names like Ocampo; Piñeiro—a name in my family—; Acevedo, my mother’s maiden name; Sanz-Valente and, let’s see…what other names are there? Well, quite a few old names, of the old families of Buenos Aires: Portuguese Jews. Now, the name Borges itself is not Jewish. Borges is the same as Burgess in English; it means ‘bourgeois,’ man of the burg, the town, as in Edinburgh, Hamburg, Rothenburg, Burgos in Spain, so that…How strange, my first name means ‘country man,’ because Jorge [‘George’ in English] means ‘man of the soil,’ you know Virgil’s Georgics, and geography is the study of the earth. Geology, the stones of the earth. Well…Geometry, measuring the earth…So that my first name comes out to be something like ‘farmer,’ doesn’t it? Of course. And my last name means the opposite; it means ‘townsman,’ bourgeois….

CMZ: A paradox.

Borges: Yes. When the Communists say that I am bourgeois, I say, “No, I am not bourgeois [burgués in Spanish]; I am Borges.” One day on Viamonte [Street]…I don’t know if you know this, but Viamonte used to be the red-light district at one time. But that was Viamonte out toward El Bajo, for example, between…well, between San Martín and what used to be called the Paseo de Julio, which is now called Alem. Anyway, it was an area of brothels. And later, the red-light district was at Lavalle and Junín, and it is there that the tango is supposed to have been invented. Except that it was invented in [the city of] Rosario, and in Montevideo too. It’s a matter of dispute as to where the tango was invented. But, what’s the difference, right? Speaking about neighborhoods of crime and prostitution, I once asked a police chief, “Which is the most dangerous district of Buenos Aires?” and he said, “I think it’s the corner of Florida and Corrientes.” (laughter) You see, because that’s where most crimes are committed, because of all those high-priced stores. And he said, “I think the most dangerous district is at Florida and Corrientes.” It’s really terrible, the high-priced luxury items sold there, when you think of the poverty of people here nowadays. It’s terrible. Years of mismanagement, the military men…. They may say that [President] Alfonsín is mediocre, but at least he’s honest, even though it may seem a contradiction in terms to call someone an honest politician.

CMZ: You wrote an essay concerning Shih Huang Ti, the so-called “First Emperor of China”….

Borges: Yes, “The Wall and the Books.” And Silvina Ocampo told me I had created a new genre with that essay, but the idea came from Herbert Allen Giles’ History of China, which he translated from Chuang Tzu. And Oscar Wilde once commented on that first translation of Chuang Tzu. Now, Chuang Tzu dates back, I believe, to the fifth or sixth century before Christ. So, Wilde was talking about the book and said, “I believe that this translation, published 2,600 years after the writing of the original book, is decidedly premature.”

CMZ: Premature?

Borges: Yes, premature. You see, Oscar Wilde was a very profound man. I think he was embarrassed by his own profundity. And he had quite an original sense of humor. He was a homosexual, you know. Now, there are many people who pretend to be homosexual. Well, he was advising an acquaintance of his, and he said, “It is not necessary to say that one is homosexual; it is necessary to say that one is not homosexual, in order not to call attention to oneself.” (laughter) You could take it for granted. (laughter)

CMZ: Well, to come back to your essay, “The Wall and the Books”….

Borges: I wish I could recall it. I don’t re-read my own work. You will not find a single book of mine in this house. And there is no book written about me here, because I try to keep the library free of those things. There are books on Emerson, Bernard Shaw, or Coleridge, or Wordsworth….

CMZ: In that essay, the Emperor of China destroys history, destroys all the books written before he became Emperor…

Borges: Well, because he wanted to destroy the past. In this way, history begins with him.

CMZ: …and, at the same time, orders the construction of the Great Wall.

Borges: In order to create a sort of magical space, right?

CMZ: It seems to me that all that has some similarity with what you have done, because you destroy certain works that you had written previously, like Inquisiciones…

Borges: And with good reason. I believe that William Butler Yeats says, “It is myself that I remake.” When he corrects the past, he is correcting himself, since the past is so, well, so plastic.

CMZ: When you wrote that essay, you didn’t think there was any resemblance between you and Shih Huang Ti?

Borges: Certainly not, good heavens. I haven’t even burned any books, except my own, which don’t count, nor have I built any walls either. No, no.

CMZ: You have built the rest of your literary work, which would be equivalent to the wall, wouldn’t it? In the sense that your later work, like the wall, is what brings you glory, while what you burn, as you point out, would be what accuses you…

Borges: That’s not the way it is at all. What I write is not as important as that Wall. It’s nothing, rough drafts…

CMZ: Others don’t agree with you on that.

Borges: Yes, but I do. Besides, there are a great many Swedish people who do agree with me: those who belong to the admirable Swedish Academy. And very sensible men they are. Very sensible, yes. Tell me, where are you from?

CMZ: From New Jersey, but I live in Fredonia, south of Buffalo.

Borges: I’ve taught several courses of Argentine literature in the United States. The first was at Harvard, “English Masters.” I received the honorary doctorate at Harvard. Then I taught another course in a small town called East Lansing, Michigan. Then another one in Bloomington, in Indiana. And…there’s another place….

CMZ: Austin, Texas.

Borges: Of course, the first and most memorable! And that was with my mother. I discovered that America in 1961. And my mother made a terrible faux pas there. There were two statues there. And they told my mother, “This is the statue of Washington. . . “ “Yes,” said my mother, “and the other one is of Lincoln.” And everyone looked at her in horror, because speaking of Lincoln in Texas Well, the Civil War, the Confederacy…. And how my mother must have felt…. You know, the American Civil War was the greatest war of the nineteenth century. Many more people died in that war than in the Napoleonic wars, than in the wars of Bismarck…. Well, than in the Wars of Independence down here. Gettysburg lasted for three days. The battles down here were skirmishes [in comparison]. Now, the battle of Junín, in which my grandfather took part, lasted three-quarters of an hour. It was fought with saber and lance. Not a single shot was fired. They were skirmishes. But Gettysburg lasted three days. Well, and Waterloo, one single day. And fewer people died at Waterloo than at Gettysburg.

CMZ: Could it be that the Spaniards had less interest in retaining these territories of South America than the Confederacy had in being independent of the Union, than the Northerners had in keeping the South in the Union?

Borges: Yes. The Spanish were poor soldiers down here, because the Guarani Indians, led by the Jesuits, easily defeated the Spanish in previous wars. Those Indians were better soldiers than the Spanish or the Portuguese.

CMZ: In your short story, “The Secret Miracle,” Jaroslav Hladík—

Borges: Oh, yes, I remember…. Well, it’s the idea that…it’s a quite ancient idea, the idea of…that time can be shortened, right? Or that it can be lengthened. Then, the time of this story is lengthened, isn’t it?

CMZ: Yes. You’re playing with time, aren’t you?

Borges: Yes, that’s it.

CMZ: But what I wanted to ask you…Hladík had a dream. I don’t know if you remember it….

Borges: No.

CMZ: In the dream—

Borges: Oh, of course. He dreamed of finding God in a map. Or wasn’t that it?

CMZ: Yes. That was the second dream in the story.

Borges: Well, I write a story one single time, and you have read it many times, isn’t that so? In that way, the story is more yours than it is mine. You’ve given more time to it than I have. It’s curious, I write them and I don’t re-read them. That reminds me of a conversation I had with the great Mexican writer, Alfonso Reyes. He was very kind to me. I used to go to the Mexican Embassy every Sunday to have dinner with him [when he was the Mexican Ambassador to Argentina]. And don Alfonso would be there, his wife, his son and I. And we would speak about English literature, actually. Well, he once said to me, “Why do we publish books?” “Yes,” I said, “I often ask myself the same question. Why on earth?” He said, “I think I’ve found the solution.” “And what is it?” I asked. “We publish books,” he said, “in order to avoid spending our whole lives correcting the errors.” And I agree. If one publishes a book, he can then go on to other things.

CMZ: That reminds me….

Borges: Since everything I publish is a rough draft, because every text is correctible. Indefinitely.

CMZ: Until it’s published.

Borges: Now then, when one publishes, he resigns himself to the text in the published form. If a second edition comes out, of course, he’ll try to correct it.

CMZ: That reminds me…. That idea of publishing in order to be able to forget the book, to go on to other things, is parallel, I believe, to something else you said somewhere, about the reason some men make love to a woman: in order to be able to forget her. Do you see the parallel?

Borges: Yes. But, naturally, if the woman doesn’t return the man’s love, if the man’s love is unrequited, he continues to think of her. But if she pays him some attention…. Yes, the ideas are parallel, of course.

CMZ: To get back to “The Secret Miracle,” in the first dream—

Borges: But, there is only one dream….

CMZ: No, the first dream isn’t the one with the map of India. It’s the one in which Hladík is running through “a rainy desert,” trying to arrive in time for his move in a chess game.

Borges: Oh, of course. Now I remember. Yes, yes.

CMZ: And you describe the game as being played, not by two individuals, but by two great families. And Hladík, in the dream, has forgotten the rules of chess.

Borges: Ah, yes, yes. Yes, but I’m not sure if it [the chess dream] was in that story [“The Secret Miracle”].

CMZ: Yes, “The Secret Miracle” begins with this dream. The very first sentence of the story is the first sentence that describes this dream.

Borges: Yes, you’re right. There are different generations, and each individual of a particular generation makes one move. So that…. Yes, of course I put that dream in because it is the opposite of the main plot. First, we have one game of chess, and several generations. And then, the writing of a drama which lasts only for one minute. That’s why I put it in the story. To obtain that contrast between the whole idea besides a game that lasts longer than many generations. Yes. That’s exactly it. But, are you absolutely sure that it’s from the same story?

CMZ: Oh, yes. “The Secret Miracle” begins with that dream.

Borges: Ah, yes. It has to be from the same story, of course. It has to be from the same one because if not—

CMZ: Hladík is the one who dreams it.

Borges: Yes, yes, yes. It takes place in Prague. I mentioned the German [the fictional Julius Rothe], so he could have read Schopenhauer, Richter, Novalis, Schiller…yes.

CMZ: In addition to the contrast between the handling of time in the dream and its function in the story, is it possible to think of the dream chess game as symbolic of war, nation against nation, rather than individual against individual?

Borges: Yes, if you like. Yes. Perhaps war is less interesting than a game of chess.

CMZ: And why do you say they were playing for a prize, but that no one could remember what the prize was, except that it was “enormous and perhaps infinite”?

Borges: Well, because it comes out better if no one any longer knows what it is. It comes out better. You know, people play chess for nothing, usually. I mean, they don’t play for money. Like in [the card game of] truco, for example. But in poker, yes, you play for hard cash, don’t you?

CMZ: Yes.

Borges: Hard cash, yes. But not truco, no. The proof of this is that no one says, “I won so much at truco.” People say, “I beat So-and-So.” So it’s something very personal. Whether one plays for pieces of candy or for money, that doesn’t matter, no.

CMZ: I know that truco is a card game, but I don’t know how it’s played.

Borges: Well, there are several ways to play it. There is a very complicated form popular in Montevideo called “truco up to two.” And then there is what is called “blind truco,” which is a Buenos Aires form of truco, the kind of truco I know how to play. It’s played with three cards. Now, in poker, for example, you have to keep playing. But in truco, it’s understood that a good player, well, he stops playing, he tells a story, tells some jokes, and tries to irritate his opponent that way. And then, when you have a flower…. Well, flower means three cards of the same suit, right? And you announce that you have a flower in verse, actually. And that verse could be, for instance, “In the gardens of Diana, I found a rosebud in the bower. Keep yourself chaste and pure if you want to be called a flower.” Or it might be something bawdy. For example, “Because he got it on with a girl with narrow hips, His peter became like a flower in an irrigation ditch.” Or you, for example, put your cards to one side and you tell a story. So that anything that might stop…. Or else you look at your cards and say, “Good grief! What a terrible hand!” Now, this could mean that you have good cards and you’re trying to conceal the fact, or that you really have terrible cards. Yes, but it’s a very slow game, a game for people who have very little to do. It’s a game made for killing time. Now poker, if I’m not mistaken, is not for killing time. It goes rapidly, and fooling around is not tolerated. Because poker, I think, was invented by adventurers in the American West, by gold miners who wanted to get rich quickly. But truco is more a pastime than anything else. A more unusual form of truco is fifteen-fifteen. Or twenty-something-or-other. And this game, played by good players, can last from five to twelve hours.

CMZ: Do people still play the game of truco?

Borges: No doubt they do. There used to be truco championships at the Paloma Tearoom, on the corner of Santa Fe and Juan B. Justo.

CMZ: Are there still championship competitions?

Borges: No. I don’t think so. I used to attend with three fellows from the Uruguayan provinces. And the chess championships at that café, the Tortoni.

CMZ: The detective story, which has labyrinths in time and space, and myths…what is the purpose of all this? Is there a purpose?

Borges: No. I’m a great reader of detective novels, that’s all. I met one of them, the one who used to sign himself…Ellery Queen. The other one died, I think.

CMZ: Dashiell Hammett?

Borges: No, no. Dashiell Hammett…he was rather a writer of novels of violent action, not of what you might call intellectual detective novels. It was…I know Ellery Queen, but…. There were two persons who wrote Ellery Queen mysteries, but I don’t remember their names. One of them died, and I met the other one. It was at a dinner for mystery writers.

CMZ: Is it possible that part of the detective narrative’s appeal is that the reader receives the impression of being a co-author, in the sense that he solves the mystery himself by the time the author does, and consequently feels a sense of accomplishment? A sense of superiority?

Borges: Superiority…. With respect to Dr. Watson, yes, but to Sherlock Holmes, perhaps not, eh? Superior to Father Brown, unlikely, right? Yes. I remember my sister was re-reading The Moonstone, a novel by Wilkie Collins, a friend of Dickens. My grandmother heard Dickens in person, because he traveled throughout England, reading two chapters of his novels. And those chapters were “The Trial Scene” from Pickwick Papers and the one about the murder of this girl by Bill Sikes. Well, according to my grandmother, Dickens used to change, not only the accent, the dialect, but his face even looked different when he read the dialogue. When he read “The Trial Scene” from Pickwick, in which, I don’t know, about from ten to fifteen characters appear, he was our Pickwick, and he was our Topman, and he was…well, all of them. And he was them admirably. And he would read those two chapters. First, “That Very Grim Murder of Nancy by Bill Sikes.” And then the other chapter, “Trial Scene,” from Pickwick.

CMZ: Are you familiar with the work of Alain Robbe-Grillet?

Borges: Robbe-Grillet?…. No, I haven’t read him.

CMZ: I ask because I think he has been influenced by you.

Borges: You see, I lost my sight for reading purposes. It was in 1955. But I have done a great deal of re-reading. Someone comes to visit me and I ask him or her to read to me. Right now I’ve begun a re-reading in that way of a biography of Emerson by [Van Wyck] Brooks.

CMZ: And people read to you?

Borges: And what else can I do? If I can’t read, I can’t write. The letters overlap. There’s no other way. One has to resign oneself. It’s easy to become resigned. I’d been losing my sight gradually from the time I was born, so that it has been a slow twilight, a long summer twilight. There was no single dramatic moment when I lost my sight. It’s been happening little by little that things have been disappearing from my sight. Like the people in my stories whom I’ve forgotten. What luck that that has occurred to me!

CMZ: What purpose does internal duplication, the story-within-the-story, have in your work?

Borges: I think…well, since the story is fantastic, the fact that there is another poet present accentuates the fantastic. The poet creating the poet who creates another work. It’s an ancient tradition. The Thousand and One Nights, for example. Well, the Quixote too. These books with stories inside…. The Chinese novel…in the Chinese novel there are many dreams and in those dreams there are others. It’s an artifice, a device. It’s natural, isn’t it? Dreams within dreams.

CMZ: In what way have you applied the ideas contained in your essay, “El arte narrativo y la magia” (“Narrative Art and Magic”)?

Borges: I don’t try to apply them. I don’t remember the essay very well. Now, I can tell you something that may interest you. The way I write…I receive a very modest revelation, you know? A mild revelation. Yes. But, then, in that mild revelation I receive the beginning and the end of a short story, right? The starting point and the goal. But, what I don’t know is what happens in the middle, in between. I have to invent that part. Sometimes I make mistakes, of course. But I always know the beginning and the end. But afterward I go along discovering if this should be written, or if that should be written. Whether it should be in the first person, the third person, in what country, in what era…. That is my work. That is my work, and I can make mistakes. So, I try to interfere as little as possible with the revelation, I believe, no? I believe the author is actually one who receives. The idea of the muse…. Of course, I’m not saying anything new.

CMZ: The way that Coleridge received in a dream the poem, “Kubla Khan,” isn’t that so?

Borges: Of course, yes. [Here Borges recites dramatically the beginning verses of “Kubla Khan”:]

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

[Then he skips to the end:]

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Beautiful. I wish I could write like that. My work is mere shavings. I am just an international superstition, which is something, but I don’t exist. I’m a pretext, a prop. A mere prop.

CMZ: No one agrees with you.

Borges: Borges agrees, said the god. (laughter)

CMZ: Which Borges?The one who writes or the one who is speaking now?

Borges: Yes, Borges or Borges? Yes, of course. My family names are Portuguese: Borges and Acevedo. And why not. When I was in Brazil—I’ve been in Sant’Ana do Livramento, in Sao Paulo—I would speak Spanish, and they would speak Portuguese, and we understood each other perfectly. Spanish, Portuguese…a dog Latin, nothing more. Le latin de cuisine…

CMZ: You have said that El sueño de los héroes (The Dream of Heroes) is Adolfo Bioy Casares’ best work. Why?

Borges: Absolutely.

CMZ: Yes, but why? Can you explain what makes it his best?

Borges: Well, because I’ve read it.

CMZ: But, you’ve read other works of his too, haven’t you?

Borges: When I read Bioy Casares…. His stories dealing with love, or with the pursuit of love, come out badly, but his fantastic stories come out well. He told me that one must write every day. And my sister, who recently celebrated her eighty-second birthday, devotes two hours a day to painting or to drawing. And she used to say that one has to versify continually in order to be worthy of a visit from the muse. So that the muse will deign to come, isn’t that so? Writing has to become a habit. But since I can’t write…well, I try to fool the secretary, but I can’t write personally, because of my vision. So I write off and on when people come to see me, and can write while I dictate.

CMZ: What are you writing these days?

Borges: There is a book with María Kodama, which are notes on travels, and it is generously illustrated with collages of her photographs. I’ve traveled a great deal, because I’ve been in Austin, Texas. I’ve been to the New York Hilton. I’ve been to East Lansing, and then to Iceland, Japan, England, Scotland, Israel, Switzerland…I was educated in Geneva. I lived for a long time in Geneva, you know. Every time I go to Europe, I make it a point to visit Switzerland. And I’ve been in France, then in London, and then they awarded me the doctorate at Cambridge, doctor honoris causa.

CMZ: Are you planning to write more fiction at this time?

Borges: Yes, yes, yes. A book of short stories which will be entitled, La memoria de Shakespeare (Shakespeare’s Memory). And it refers, not to his memory, but to his fame, yes. The memory he has left us of him. Yes, La memoria de Shakespeare. I’m working on that, and on a book of poetry too. And besides all that, I have to write—good Lord!—I have to write ninety-four prologues for ninety-four books. That would take me at least a hundred years to write, wouldn’t it? I’m a very slow writer. There’s one on Bernard Shaw, for example, whom I love very much.

CMZ: In “Hombre de la esquina rosada” [translated into English as “Streetcorner Man”]…

Borges: A terrible story. Let’s not talk about that.

CMZ: No, no—

Borges: It’s phony….

CMZ: There’s something about it I’d like to know.

Borges: No, no. It doesn’t interest me in the least. I’m ashamed of it, thoroughly ashamed of it. [Norman Thomas] DiGiovanni told me it seemed like an opera, and he was right.

CMZ: There’s a character in it named “La Lujanera,” and, of course, the most obvious reason for the nickname is that she simply comes from the town of Luján in the Province of Buenos Aires. But, is that the reason you called her that, or was there some other reason?

Borges: No, no. Because she’s from Luján, which is not far from here. I don’t see any other reason there could be.

CMZ: Someone has suggested that it is because “la lujanera” is a name for an unlucky card.

Borges: Ah, yes, possibly. I believe I read that in Ascasubi. But I wasn’t thinking about that when I gave her the name. It’s just that, since everyone had names, this one came along with a nickname. So, instead of So-and-So…put away Jane or Mary, and she was “La Lujanera.” It seems right, doesn’t it? I’m just suggesting Luján, which is the name of a town.

CMZ: You once said, “I think Conrad and Kipling have demonstrated that a short story—not too short, what we could call, using the English term, a ‘long short story’—is able to contain everything a novel contains, with less strain on the reader.”

Borges: Absolutely!

CMZ: You still feel that way.

Borges: Yes. Even though I may not be the one who said it, I agree. (laughter) Yes, I think so. I think I’ve chosen good examples, no?

CMZ: Well, [Enrique] Cadícamo has said that the lyrics of a tango, which has a duration of about three minutes in its performance, can express perfectly well everything that can be expressed in a ninety-minute motion picture. Would you say that this is basically the same idea you express with regard to the short story and the novel?

Borges: Yes. Cadícamo is so bad that anything he says is usually an error, right? Then this is the only thing he’s ever done right. Cadícamo is so bad.*** Everything he has written is so phony. No one uses Lunfardo [Buenos Aires slang], for one thing. It’s an entirely artificial dialect, Lunfardo is. Everyone used to tell him, “Don’t write, my friend,” but he goes on writing. All his friends advised him.

CMZ: Why was the Argentine tango so popular in Paris between the two World Wars? Why Paris?

Borges: I don’t know. I can’t answer that. And if someone asks me to explain my own country, I can’t. I don’t understand it. Or if I’m asked to explain my own work, even less so. I myself don’t know who I am.

CMZ: You are the instrument of an archetype that is trying to enter the material world, aren’t you?

Borges: Well, yes. That’s a good explanation. Walt Whitman said, “I don’t know who I am.” And Victor Hugo, more prettily: “Je suis un homme voilé par moi même; Dieu seul sait mon vrai nom”; “I am a man hidden by myself; God alone knows my real name.”

Epilogue

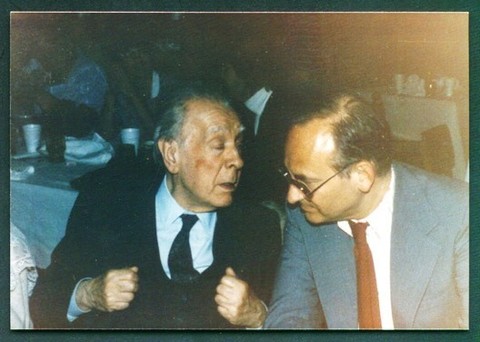

One year after this interview—one year before Borges’s death—I had a chance to converse informally with Borges several times, at dinner and at social events, such as during a symposium on his work at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania. The evening preceding the Symposium, I went up to Borges (who was accompanied by María Kodama) simply to greet him and to shake hands. Thinking that after the passage of a whole year he would not remember me, I said, “I met you at your home last year, where I interviewed you. I was with William Shand and…” He grasped my hand firmly, smiled, and interrupted unhesitatingly to say, “Oh, yes, I do remember. Of course, and you sang ‘The Raggle Taggle Gypsy.’” Then, without loosening his grip on my hand, he sang several stanzas of the old song. I was flabbergasted. He was almost eighty-six years old. Still, he remembered immediately. The next day, he listened to my paper on him and commented to me later that I had discovered things about his writing of which he himself had not been aware. During that conference, I had the opportunity to chat with him for hours. This was an unforgettable experience, and the direct result of my trip to Buenos Aires in 1984.

—Clark M. Zlotchew

* Juan Manuel de Rosas (1793-1877): Leader of the Federal Party, Governor of Buenos Aires Province 1829-1832 and 1835-1852.

** Victoria Ocampo: Founder of the journal Sur, the most influential literary publication in Latin America from the 1920s to the 1940s. She has collaborated on anthologies with Borges, Bioy Casares, and her sister Silvina Ocampo.

*** One of the most popular tango lyricists of Argentina, most of his production took place in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Some of his lyrics employ a sprinkling of slang expressions, although not nearly so much as certain other tango lyricists, e.g. Francisco Marino, Enrique Santos Discépolo and many others.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) was an Argentine writer and poet, and considered one of the most significant literary figures of the 20th century. His works, known for their intricacy and intellectual depth, have profoundly influenced the realms of literature, philosophy, and the imagination.

Borges was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and was brought up in a household filled with books and a deep appreciation for literature. From an early age, he exhibited a voracious appetite for reading and embarked on a lifelong journey of intellectual exploration. Borges delved into a wide range of subjects, including history, mythology, mathematics, and the vast labyrinth of human thought.

His unique blend of genres, including fiction, essay, and poetry, showcases his masterful storytelling and penchant for blurring the boundaries of reality and fiction. Borges often weaved intricate and metaphysical narratives, blending fantastical elements with philosophical musings, creating works that challenge conventional notions of time, identity, and perception.

Borges’s notable works include Ficciones, The Aleph, and Labyrinths, which exemplify his fascination with intricate mazes, infinite libraries, and enigmatic encounters. Throughout his career, Borges received numerous accolades and awards, including the Cervantes Prize, and his literary legacy continues to captivate readers worldwide.

Clark M. Zlotchew is SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Spanish, Spanish Dialectology and Linguistics and Literature in Spanish Language, Emeritus. He has had 19 books published; 13 of them in his professional fields (literary criticism; literary interviews with Latin American authors, including Borges; books teaching Spanish language at different levels; translations from Spanish of poetry and short fiction) plus five books of his fiction (three collections of his own short stories; two thriller novels) and a collection of his poetry.

Zlotchew has had over 70 scholarly articles in Spanish and in English published in learned journals on five continents. Newer poetry and fiction of his has appeared in Crossways Literary Magazine, Baily’s Beads, The Fictional Café, and many other literary journals in the U.S. and abroad. Earlier fiction of his has appeared in his Spanish versions in Latin America. His website is http://www.clarkzlotchew.com.