1: Explosion in a Mask Factory

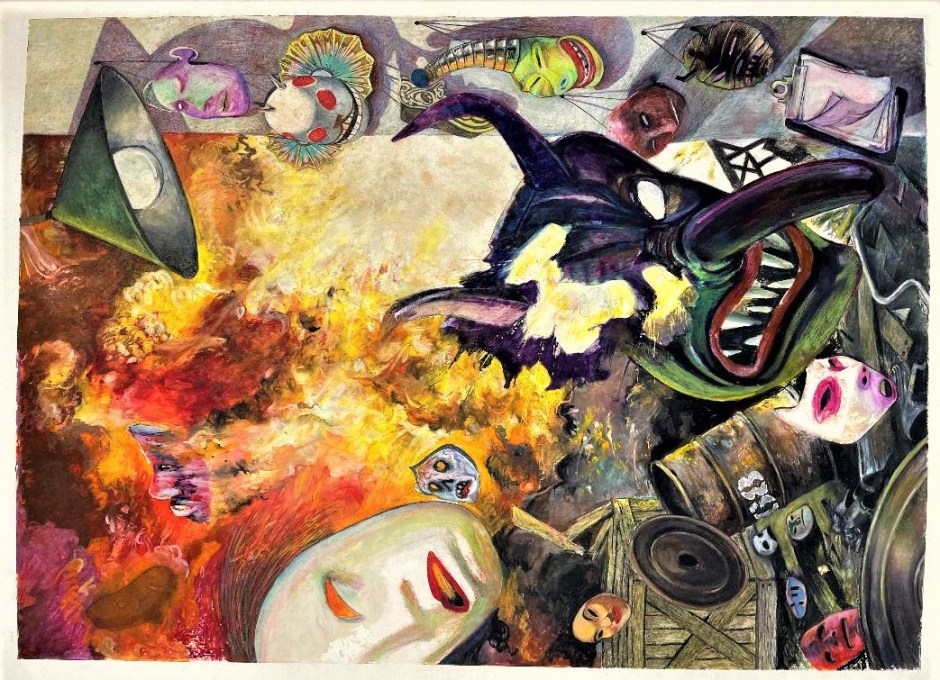

I am known in some stations as The Crisper Whisperer. I am summoned because it has happened again. The phone booth glass is crazed on the corner, five Brooklyn blocks from the blast. Four blocks, the Gowanus boils. Three, melt masks sail like napalm jellyfish. Two, drool ghouls drop to goo tree branch and powerline, drip pizza-cheese strands of face from above. One block, me, hurrying to the scene, the air a tell of accelerants and guile. And bodies, always nine, charred in pugilist pose, at rest as perfect evidence before axe and hose ruin the ruin, gum up the story with retardant just as bad over time as any quick burn toast of lung. Run run, flash them the badge and run, yank on your own mask, suck on your own air, dodge the sparks and run run into the core. The big guys wave, point picks into smoke to the shop floor sacrifice: standard circle of crisp contenders in chairs, burned shaker plain, all-black minimalist installation art to char. That’s the eye that solves the crime, over and over the same one: circle of nine burned, sky of melted masks, and movie mayhem at the core.

Somebody said, Burn the fucker down. And it’s my job to find them, stop them, arrest them. Or join them. As one of the burners, or the burned.

Charley one of the firefighter/cineastes I know from the old days approaches my tapeline cautiously. He mouths GOOD? I appreciate that but I’m already inside and up thumb a go away. He turns and opens his hose on beams swarming with sparks. A wall of greasy steam cuts me off from their world. Good. Any interference (macro, nano, quantum) will degrade and erase. It’s started the moment I step over the line. But at least I can factor me into the mix. I think. So, first things: who are these nine whose time has come? How long before mine?

I take establishing shots and close-ups but I can recognize most at first glance. I pull up their bios and begin.

2: Nine Pugilists

The phone booth glass is crazed on the corner, five Brooklyn blocks from the blast. Four blocks in, the Gowanus boils. Three, melt masks sail like napalm jellyfish. Two, drool ghouls drop to goo tree branch and powerline, drip pizza-cheese strands of face from above. One block, me, hurrying to the scene, the air a tell of accelerants and guile. And bodies, nine this time, charred in pugilist pose as perfect evidence before axe and hose ruin the ruin, gum up the story with retardant foam. Run run, flash them the badge and run, yank on your own mask, suck on your own air, dodge the sparks and run run into the core. The firefighters wave and point the way with picks like iron fleur de lis. The sacrifice: standard circle of contenders for memory, burned shaker plain, black minimalist installation art to char. That’s the eye that solves the forgetting crime: circle of nine, sky of mask, heart of ash.

Somebody says, Burn the fucker down, and it’s my job to I.D. the bodies, to id the scene before it’s all gone. I tape off the circle and begin.

Id the Scene

Charley, one of the firefighter/cineastes I know from the old days, opens his hose behind me on some fallen beams, swarming with sparks of neurons like fire ants. A wall of steam cuts me off like a hospital curtain from their world. Good. Any interference (macro, micro, nano, quantum) will degrade and erase the scene. So: who are these nine whose time has come? How long before mine?

The “Other Men”`

Number one is actor Lyle Talbot, obscure-famous for Plan 9 From Outer Space and Ozzie and Harriet after a forty-year career in supporting roles as “the other man” in hundreds of movies, TV shows, and plays. He’s still got the Roman/Pompeiian profile and nose of his matinee idol beginnings as a leading man in waiting. He worked and worked. “It’s simple, really. I never turned down a part. Not one—ever.”Major studios stopped grooming him for bigger things after his leadership in the new Screen Actors Guild, and the parts got smaller and crummier.His seared-bald head recalls his Lex Luther role in the rock-bottom serial Atom Man vs. Superman from 1950. He was a trooper who acted his heart out, even as the off-screen narrator for Mesa of Lost Women in 1953, a film that one critic said was so bad “that you are prompted to ask if it is actually evil.” He played Commissioner Gordon with strange gravitas in the terrible low-budget 1940s Batman serial. Ozzie and Harriet on TV gave him a reprieve of sorts and a bigger audience than he’d ever known in films, playing the ultimate irritating suburban neighbor of the Nelsons, Joe Randolph.

Number two is actor Jackie Coogan, once the most beautiful and famous boy in the world after starring in Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid in 1921. Forty years later he achieved another kind of fame as Uncle Fester in TV’s The Adams Family. In between was an arc like Lyle Talbot’s: a long, mid-career exile to B and Z movies playing thugs and evil scientists, like Dr. Aracna, creator of spiders as big as men and women as deadly as spiders in Mesa of Lost Women, (narrated by Lyle Talbot).

Number three is actor Morris Ankrum, who parlayed one persona (authority figure) into a thirty-year career and over two hundred and seventy films and TV appearances in supporting roles as the judge, the general, the Indian chief, the police chief, the lead scientist, the trail boss, the posse boss, the sheriff, the bank president, the American president, the martian leader, the spaceship captain, the ship captain, the captain of industry.Unchanged in different costumes, hairstyles, scripts, settings, locales, and times. But always the same Figure of Authority.

Number four is Thomas Brown Henry, another supporting actor in hundreds of Western/sci-fi/crime movies and TV shows, playing the same authority figure (general, judge, scientist, etc.) for more than thirty years. He was distinctive for an expression of unchanging grimness, and a hawk-like nose of commanding angles.His roles included: Captain Raoul de Gaucort, Captain Kerrigan, Colonel Gabriel Peter, Commissioner Mermat, Colonel Carter, General Bolthouse, Vice Admiral A.D. McIntosh, Colonel Tom Sturgeon, Professor West, Captain Fletcher, Dr. Leventhal, Reverend Bascomb, Judge Parker, Professor Charles Ruch, Marshall Adam Polk, Dr. Parks. Like the optical illusion of the faces in profile or the fluted vase, it is impossible to hold the image of Morris Ankrum or Thomas Brown Henry separate in your mind without them melting into each other…

A flaming meteor mask falls into the circle and explodes. I’m thrown into the burning sky. I’m flying. I’m burning.

3: The Sky is Burning

I hit with a thud, roll with a crunch. Broken stuff, burned stuff. Blur of gurneys, syllables of meds. After a time I’m more or less patched, can walk to the doc who cuts bone and bandage to the chase: “I’ve read your report. You were only able to I.D. four of the nine before the fire face fell.”

“They were all B-movie actors who played the same roles, over and over for decades.”

“Your firebug had a point?”

“A pattern. Elements of the memory game.”

“Remind me.”

” My dad and I played it, watching old movies on late-night TV, he’d quiz me about the actors, their names, their filmographies, their lives. Never the stars, always the supporting cast. Sometimes people with three lines. No lines. A cab driver who gabs, a cleaning woman who screams. Faces we would see in the next film, and the next. “

I stop to consider this doctor of mine I have long known yet cannot name. Nameless too the clinic, or my occupation, or the purpose of my investigations, for which I have been summoned, burned, broken, ragdoll flung to singe. The doctor looks at me with no recognition of my abandonment. She has the face of a knowing confidant. I wish I had a doctor like her to confide in.

4: Masks Off

But then maybe she does see me, because she says, “I know you don’t know why you are sent again and again, so I’m going to tell you, and then you will remember. You’ve had two heart attacks. You’ve been on the wrong end of a gun. The wrong edge of a knife. Each time there’s an explosion and a fire, something more is lost. Maybe you’re the only one who’s not armed.You are the only one to be sent. because the factory is you.” I wait for more. Wait and wait. Is this mere solace of eschatology? Surely there is more. I need more. Window washers out of sight outside draw a gurgling squeegee down the glass behind me. Birds sing. Our time is up and we stand and nod goodbye.

I walk home with the bounce of insight. Of course! I am the factory. The burned figures are the remains of illusion. The pretty masks are not just removed but ripped off, blown away. The victims are actors. They are obscure actors. They are the obscure actors of my childhood. They are the icons of failure my father committed to memory, then passed on in remembering games to me. Because he was trying to prepare me. Trying to protect me. Trying to keep me from losing my fucking mind. Some prisoners in cells play imaginary chess games. Visualize every inch of their boyhood room. Or that prisoner in Siberia, who was it, Josef Czapski, who gave the other prisoners classes about Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, from memory? But as I am thinking this, I have lost my way through streets I know and don’t recognize, the knowing and not knowing simultaneous as the optical illusion of the faces or the vase, Morris Ankrum or Thomas Brown Henry. There, Dad. I’m completely lost in this city, but I can remember the Other Men.

And then it hits me: there were some movies where Morris Ankrum and Thomas Brown Henry appeared together. The impossible matter/antimatter meeting so fraught in the Enterprise engine room happened in many movies, the secret quantum superimposition carried to madness in analog, burning a hole in light to haunt three movies from my early childhood some of the most terrifying and traumatic experiences of my early life: The Beginning of the End (1957), about an invasion of giant grasshoppers; Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), where withered aliens in robotic suits piloted rampaging stop-motion saucers; How to Make a Monster (1958), with a Hollywood make-up man whose masks turn actors into maniac killers.

5: The Phone Booth is Crazed On the Corner

Franz Kafka on Yiddish street theater: “The sympathy we have for these actors, who are so good and earn nothing and in other ways too get far from enough gratitude and fame, is actually only sympathy over the sad fate of many noble endeavors and above all our own.”

In the meantime,

the phone booth is crazed on the corner.

How is it there is a phone booth at all? Phone booths are long gone. The factory is long gone. Yet there they are, crazed in glass and mask, shards of both hot as hell and hot hail. Black rain. Running Away is now Running To.

To the factory.

The doc says the place is me, but the place is a place. A Civil-War era armaments factory of soot brick and pentimento sign; saw-tooth roof and coal chute jut; smoke stack poke and water tower hunch. Where you are headed is the arched gate, under tin chimney bent to Ulysses stogie or tumbled top hat yaw. Inside dank overhead beams raked with long-ago teams of pulley brigade, now nesting pigeons and scramble hatch bats, acrobat rats above foundry pit scabbed with old coke, like the poxed backs of prison labor Irish or Coolie bobs. Beyond, tracks crisscross in narrow-gauge quaint with memories of freight, urged slow and ugly from barge to donkey to winding cul-du-sac, potash alley, or final squatter laudanum den. There you’ll find the ninth brick from the bottom, the loose one hiding the key.

6: Nine Bricks

Unlike before, the factory is not burning and ringing with sirens and shouts. It’s empty and silent, till plaster crunches underfoot, and pigeons rustle overhead. I follow big boot tracks back outside to an empty courtyard. In the corner is a stone shed barely visible against a wall. I know without knowing it is a remnant of an airless redoubt against a Confederate attack that never came, later linked to the main building with a brick tunnel stoop height. Inside the shed is a candle and an open matchbook with one match. I light the candle, lift the grate in the floor and go in the tunnel. In a few yards the tunnel ends in a room. I dribble some wax and fix the candle on a shelf. There is an old bottle with a black cork, a mouse skull, and graffiti of a naked woman with a monkey on a ball and chain dated 1897 with an outsized 9. The third shift nickel boys found the room and made it their own, what office culture might now call a break room, but the gangs back then named The Hide. This is where they played Soapy Smith games with shot and shell, dreamed long cons with gin and knives. This is where they hid the key, behind the ninth brick up from the floor, and where I retrieve it, pocket it, head back through the tunnel, back out to the wheelhouse, and the door I can now unlock.

7: The Belmont Casket Factory

I insert the key. The lock gulps with a chortle of tumblers. The room takes flight, a cage in search of a bird, but settles for my head. Then the difference—room, head—doesn’t matter. Inside both is a waiting room, mid-century dentist’s-office style. On the walls, display cases of masks instead of molars. Frosted glass door with little comedy/tragedy masks and the word BELMONT. I take the couch, the plastic sounds resigned. There’s a plant that doesn’t need light in a pot.

Early childhood memory: a giant red neon sign at night in downtown Columbus, Ohio spells out:

B E L M O N T C A S K E T S

LEAD

COATED

STEEL

Their deluxe model, the “Masterpiece” was the final resting place of Marilyn Monroe. Belmont Caskets also housed the charred bodies of 322 inmates from the over-crowded and notorious Ohio Penitentiary, burned to death when a fire broke out in 1930. The prisoners were mostly black, mostly killed because the guards would not open the cells. The dead did not receive The Masterpiece, or any other casket. Their remains were piled up on the factory floor, only because the Belmont Casket factory was right next door to the prison. The frost glass door opens and a small slender man steps out. I stand and he shakes my hand and nods to the cases with masks. “Do you think you have what it takes?”

8: Do You Have What It Takes?

The small man at the door says again, “Do you have what it takes? ”

I point to the name on the frosted glass. “There was a Belmont Caskets in Columbus, Ohio. And there was a fire at the penitentiary next door to it. They put the bodies of prisoners…”

“There’s been no fire.”

“An explosion. I’m an arson investigator.”

“Are you?”

“They call me when it happens.”

“You mean before it happens? You’ve got the wrong mask factory. I don’t see mine exploding any time soon.”

This seems funny to me, but the small man isn’t smiling. He looks at his watch. “If you’re not here for the interview…”

“You asked me if I had what it takes. What it takes to do what?”

His mouth crumples with a sigh. “I’m not cut out for this HR stuff. I make masks, alright? To very exacting standards. This new Eneagram stuff Bob gives me is bologna. I’m supposed to find out what type you are. There are nine of them, for christ’ssake.”

“Who’s Bob?”

“My brother. He’s the real boss. I’m Rob. I just make masks.”

“I would be making masks?”

“Everyone has to work up to that. The starter position is Shop Floor Custodian. Cleaning, essentially.”

“I don’t think I want to be a cleaner.”

I expect the small man, Rob, to be angry, or at least show disappointment. Instead, he nods wearily and turns a blank face to the door. “OK. That sounds like Number Four: The Individualist. Or Number Five: The Investigator. Let’s go see Bob. He’ll get you oriented to the real thing.”

“I don’t want to be a cleaner.”

“Yeah yeah. If you did I’d send you packing.”

“But you said the starter position…” He waves away the idea and opens the door. “This has nothing to do with clean.”

9: Nine Personalities

The small man named Rob leads me into a short hallway, and then opens the first door on the left for me to enter. Rob says, “Bob will be with you shortly.” He closes the door and I am in the same waiting room, with a cream-colored plastic couch, potted plant that needs no light, and Plexiglas display boxes of masks on the walls. But in this waiting room, there is faint and rhythmic mechanical pounding beyond the inner door. Its frosted glass registers with a tiny shudder, and there’s a thud in my gut. One leaf of the plant shows an infinitesimal quiver. Before I can sit down again a small panel in the far wall slides open. It is in line with the row of boxes on the adjoining wall. A long transparent box, about the size of two shoe boxes joined end-to-end, emerges from the opening and races horizontally along an unseen track in the wall, toboggan-like, to pass through the clear boxes, which I see now are missing sides. At the same moment the masks, hinged on the walls on one edge, flip open with a vending machine clunk. The faces all turn right in the manner of soldiers on parade. From the left, the transparent box punches through the masks, which rip and yield like tissue paper. At the end of the track the box slams to a stop. The masks snap back to their position flat against the wall. They gape forlorn around ragged holes. The thuds go on.

I look at the box. Inside it, coffin-like, a doll. But more than a doll. A figure. An effigy. A realistic sculpture in transparent plastic of Rob.

The inner door opens and Rob emerges. He walks by me without comment and picks up the plastic coffin with his miniature likeness. “I’d like to configure this so it can go around the room and return on its own, but there isn’t enough momentum to make the turn.”

I said, “I guess it can’t just go back through the masks again, right?”

He looks at me long and carefully before speaking. “Rob said you were a Four and Five. I’d say a good share of Eight as well. ‘The Challenger.’”

“You’re not Rob?”

“I’m Bob.”

I nod at the figure in the box. “Is this you, or Rob?”

“At this scale it’s moot.”

“I’d say at our scale it’s moot. You look exactly the same.”

“At first.” He hands me the box and I follow him through door. “Over time you’ll see how different we are.”

10: A Secret Note

We enter a third waiting room. On the walls are other transparent boxes, horizontally arranged like caskets with clear plastic figures within. Bob takes the transparent box with his own likeness (or his identical brother’s) and adds it to the row. He opens the next door.

Metal steps descend to the factory floor, where Bob draws me close to be heard over the din. He comes alive describing the line of stamping machines pounding the hot rubber air, and the giant mixing bowls holding an amber soup of latex in a cymatic shiver. He grips my arm and I feel electric delight watching the liquid trough to work stations of standing women, who pour the latex into molds, peeling away raw “issue” and passing them on to waffle-iron-like “grillers,” then to finishing tables of sitting women to unpeel and cure under cheesecloth, then on for trimming, painting, sewing, gluing, stapling: strings or straps, facial hair or extra appendages, (nose extensions, horns, antennae, third eyes). Scurrying around us are pale girls in stained coveralls (perhaps the position I have declined), loading the masks onto carts to the stamping machines, where they are put on conveyer belts by another team and fed into the presses for some final, unknown process. One of the girls bumps my arm moving past, and I feel hot fingers press a paper scrap into my hand. Bob doesn’t notice and urges me forward to the next station. I pocket the paper and ask if I can be excused to use the bathroom. Bob points it out, and I tell him I will be right back.

11: There’s an Empty Howl Behind My Face

In the latched bathroom stall I read the note the factory woman has slipped to me. In round penciled cursive it says:

help us

On the other side in pressured all-caps:

GET OUT OF HERE

NOW

There is an empty howl behind my face. I’m scared, really scared. Scared in a way that shows me I’ve been scared for a long time. My legs tremble and I collapse on the toilet seat and reel with the crashing cold waves from inside that say: what you’ve been calling strong, isn’t. What you’ve been calling whole, isn’t. What you’ve been calling me, isn’t. It’s all contingent and precarious and fragile and brittle. My self is a house of cards. The slightest nudge, the faintest tap, the gentlest shift, the one-card-too-many addition, and I am all over the floor, nothing but nothing of a desultory game of 52 pick up, sucker.

The pounding of the machines on the factory floor.

The pounding at the beginning of Fritz Lang’s Testament of Doctor Mabuse.

The cards on the floor jiggling to the beat.

There’s a knock on the stall door. I say, “Just a minute,” and someone answers, “It’s OK. This came for you,” and slips a paper under the door. They leave and I pick it up and read:

""Jazz and Emergence--Part One: From Calculus to Cage, and from Charlie Parker to Ornette Coleman: Complexity and the Aesthetics and Politics of Emergent Form in Jazz." Pdf." by Martin E. Rosenberg

Your other reading history:

The Acousmêtre and Contrapuntal Sound in Lang's "M." and "The Testament of Dr. Mabuse" -

Emily Bahr-de StefanoPure experience and True Detective: Immediation, diagrams, milieu -

Julia BeeA DIFFERENT STORY - Seduction, Conquest and Discovery

- Finn Janningsounding. body with bar-plate-rack -

tara pageCinemas and Worlds -

Claire ColebrookSexual Indifference -

Claire ColebrookThe Readymade: Art as the Refrain of Life -

stephen zepkePhilosophical Toys as Vectors for diagrammatic creation.

The case of the fragmented Orchestra. In: Theory of Science -

Claudia MonginiDeleuze and Badiou on Being and the Event -

I don’t know how long I look down at the paper. I drop it and read the note from the woman again. My hand is trembling and I turn the paper over, one side and then the other, help get out back and forth, faster and faster, like the thaumatrope, the spinning optical toy of the bird in and out of the cage, some in-between switcheroo where both imperatives meet. Quantum stuff. I do this long enough that another part of me detaches and roams around the little stall world. I remember an old friend, one of the best storytellers I’ve ever known, how he could make the tiny dilemmas of his private anxieties (what I can now recognize plainly as obsessive-compulsive disorder) into titanic, metaphysical dramas of breathtaking suspense. One especially unforgettable tale: he is immobilized on the toilet seat, unable to move. It’s getting later and later, there’s a pounding on the door, c’mon hurry it up in there but he can’t move without completion of an elaborate ritual. Can he finish it in time without forgetting a step? He must count the tiles on the bathroom floor, in a precise sequence and pattern, then spin the toilet paper roll till the paper touches the floor, to be ripped away, balled up and flushed. Then count, spin, rip, ball, flush again, nine times. And with each spin making a soft trilling sound with his mouth (something like a bird’s weee weee weee weee).

I try it. I spin it. weee weee weee weee.

The pounding stops. I rush out of the stall. I open the bathroom door. There is a wall of flame.

12: Can You Hang a Picture on a Wall of Flame?

“If prose is a house, poetry is a man on fire running quite fast through it.” — Anne Carson

(The singing flame: a flame, as of hydrogen or coal gas, burning within a glass tube and adjusted so as to set the air within the tube in vibration and produce a high, pure voice. A chemical harmonicon).

Can you hang your picture on a wall of flame?

Can you write your poem on a one-way train?

Can you teach a language that you barely speak?

Can you do it all as a prayer on the cheap?

“I do not believe in art as therapy.” — Anne Carson

I’m coughing and running through a burn pit fog. I make it out of the factory with a singed cuff and soles hot and soft as summer tar. My pockets are empty of pleas or portents, academic hyperlinks or de-subjectivizing processes. Once outside I don’t look back. I recite and remember: wiggling my children’s toes to The Five Little Piggies, suspensefully building to the last one,

and this little piggie cried wee wee wee wee

all the way home

I cry something all the way to somewhere, just in time to wipe away tears and soot for my therapy. I tell her about my days: The job is fine. The marriage is untroubled. The exercise is daily. The appetite is strong. The art and writing are productive.

But the sleep.

The sleep.

She does the thing straightening the flower vase, the pad and pen, the box of tissues on the table between us. She has attained the symmetry where they have attained the symmetry. Then she violates it with a gentle push of the tissues to my side of the table. She points to her own face, a space under her left eye. I tug out a tissue and wipe away the last of the ashy tear smear from mine, maudlin, I imagine, as the runny mascara of Tammy Faye, the melting hair dye of Rudy G. There.

I wad the tissue and toss it on her symmetrical table.

“Fuck you.”

13: Luck and Magic

The therapist (I will name her now, her name is Jackie) gets up and I expect her to open the door and usher me out. Instead she retrieves a book from her desk and puts it before me in the space left vacant by the tissue box. Symmetrical Jackie. The book is The Entertainer: Movies, Magic and My Father’s 20th Century by Margaret Talbot, daughter of Lyle Talbot, the first of the burned Other Men in episode 2 of Explosion in a Mask Factory.

I say, “I guess you were listening.” She rolls her eyes. There is a folded paper bookmark stuck in page five. Printed on the bookmark is another academic citation:

The Making and Unmaking of Sense: Gilles Deleuze and the Practice of Creative Philosophy by Helene Frichot

I stare long and hard until Jackie breaks the trance. “Hey, don’t worry about that. Look at the book.”

She has underlined sentences in pencil. I see the words without reading them. Jackie gives a raspy groan. “Ahhh! Jeeze. Here.” She takes the book back and drops her glasses onto her nose to read with a carsick cadence:

“…He led a life of surfaces, and there is, of course, a great loss in that. There were things he never understood—about himself, his wives, his children. He was a great raconteur with a diamond-sharp memory, but the stories he told were all plot. The psychological why of what people had done—left Hollywood in a hurry, abandoned a beautiful wife, drank to excess—was left vague, even the question unasked. When I was a kid, I used to press him for the why, and then eventually I got frustrated and stopped. The thing about living as a pre-psychological, non-introspective person, though, is that when you make a success of yourself, it tends to confirm a belief in luck and magic…”

I say, “How many years did you smoke?”

“Ahhhh Jeeze.”

14: A Life of Surfaces

I gaze at the masks in cases on the walls. They have been grouped for complementary form and color, mixing up time, culture, character or use: a Greek Tragedy mask, a Micky Mouse mask, a Yoruba spirit god of painted wood, horns and long black hair mask, a nail covered blue Hellraiser mask, a vintage Ben Cooper Halloween Hag mask, a black, white haired Hanya face with red fangs mask, a rubber Captain America mask, a Commedia dell’arte carnival mask, a drooping Scream mask, a Scaramouche cavalier with a Cyrano nose mask, a grinning Día de los Muertos skull mask, a Jurassic World Velociraptor mask, a silver robo-bug Power Rangers mask, a Mardi-Gras purple bejeweled eye-mask, a Boris Karloff Fu Manchu mask, a vintage Ben Cooper Clown mask, a Harlequin fool mask, a Snake Woman mask, a Dog Man mask, an orange Ben Grimm Thing mask, a beaked medieval plague-doctor mask, a white with gold lightning bolt Lucha Libre mask, a vintage Ben Cooper Vampira mask, an inside-out William Shatner as used by Michael Myers in Halloween mask, a Darth Vader mask, a sutured Sally Skellington-Nightmare Before Christmas mask, a brooding green Hulk mask; vintage Ben Cooper Mummy mask, a Donald Trump face melted into a pink puddle mask, a skull with blinking eyes covered in neon Our Lady of Guadalupetattoos mask, a howling face with hands over ears from Ensor’s “The Scream” mask, a vintage Ben Cooper Creature from the Black Lagoon mask, a vintage Ben Cooper blond queen mask, a vintage Spirit Casper the Friendly Ghost mask, a vintage Spirit Betty Boop mask, a smiling Noh Theater mask, a black geometric-marked Squid Game mask, a classic Emmet Kelly clown like the kind always worn by criminals in 1950’s heist movies-type mask, a Roswell souvenir alien mask, a shiny leather and zippered dominitrix mask, a padlocked Man in the Iron Mask mask, a Groucho Marx glasses, eyebrows, nose and mustache mask, a gold-visored Halo helmet mask, a pink rubber elephant head Ganesh mask, a black KN-95 Covid mask.

15: Smolder Like a Lip Stick

I tell Jackie the therapist that having masks on her office walls is straight out of Freud or Jung, “And you’re not one of those guys for sure.”

“Maybe I just like masks.”

“Sometimes a mask is just a mask?”

She’s got on dark chocolate lipstick today. I can’t make up my mind about it, or her. She says, “We gotta talk insurance turkey. They are discontinuing your coverage because we’re going on too long ‘without measurable progress on identifiable goals’ blah blah. I’ll help you with the appeal letter. We can get another twenty sessions. Tell me what progress you’ve made toward what goals.” After I don’t respond she starts clicking her pen.

“Do you have to do that?”

“Indulge me. In your own words….”

“Patient continues to struggle with diffuse anxiety and depression, and the debilitating effects of elaborately obsessional defense mechanisms, latent autistic rituals and intellectualization of internal processes that sometimes assume a near-delusional effect on his daily functioning, impeding a realistic self-image and healthy social relationships, while—”

“Never mind. I’ll write it myself.”

“What.”

“Have you been back to the factory since last session?”

“They offered me a job. They want me.”

“It’s good to be wanted. As long as you’re clear about who wants you. And for what. ”

“I see you’ve got six rows of masks with seven masks in each row, with three more above your desk over there, which makes forty-five, which is a multiple of nine. And nine is also the sum of four plus five.”

“I’ll e-mail you a draft of the appeal for the insurance company. Please, don’t thank me.”

“I’m sorry to be such a pain in the ass.”

“No, you’re not. I’ll see you next week.”

I go to the door and she says, “And be careful.”

In the hall Jackie has a bulletin board. There is a new posting on fuchsia paper:

How to Respond to the Fire Emoji

- Fight their fire emoji with more fire emojis.

- Show appreciation with a heart-eye emoji.

- Use a blush emoji.

- Answer with a smirk emoji.

- Show confidence with a dancer emoji.

- Tease back with a wink emoji.

- Send a meme of a firefighter.

- Respond with a gif of a water bottle.

- Respond with a gif of an exploding matchbook.

16: A Gangrene of Largese

I’m late for my appointment and call an Uber. A few blocks from the factory we’re stuck in traffic and crowds. It’s the corner with the new Trump statue. The driver snarls, “Look at ‘em. On their meat like dogs. Flies.” Trucks with Trump steaks make regular meat drops to build crowds.Part of their avidity is practical; better to pounce and smother the meat fast than let it linger on the ground, where months of these red meat drops have turned the base of the golden Trump statue into a maggot-writhing gangrene of largesse. Even the stench does not deter the deep believers, who burrow into the rot looking for the fabled Trump Memorial Crypto medallions. The driver says, “There they go! Digging for that pure, pure crypto gold, beautiful crypto! Lookit at their fingers, all ichor-encrusted, splayed into white power and Q-Anon pitchforks. And with enough salt and barbecue, very well-done and done again, and enough love for the country, and enough love for the one stable genius towering over all, and lots and lots of ketchup, you can fill your belly to bursting, keep it all down, wear the smell of death in your hair, your own natural hair, and in your skin, your bronzed, beautiful skin, and in your clothes, and ties, your long, long ties, for a long, long time. Until you are tired of winning, and finally throw it all up and eat it again, just to prove your mettle, show your love for that freedom, that free, free freedom, to eat puke!”

“Amen, brother.” I tell him to pull over and give him an extra tip.

“You sure here? They look kind of ugly today.”

“Uglier every day.”

He hands me his card. FELIX. “Ask for me anytime, man.”

I thank him and get out. The air is a bouquet of buzzards.

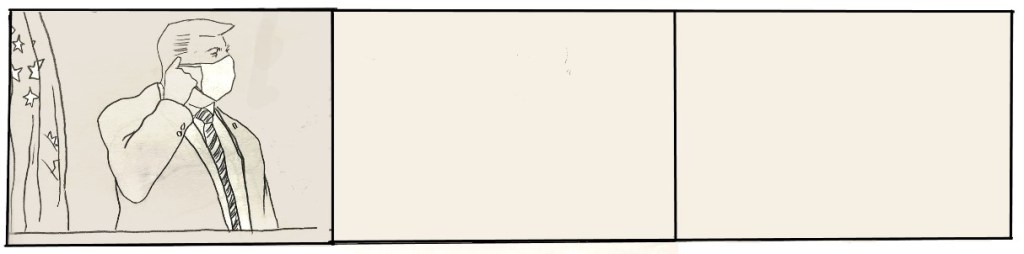

17: “Little Donald said, ‘I Won’t Wear No Stinkin’ Mask!’”

Facing the MAGA crowd, a small woman with a gray ponytail and oversized wool coat waves a blank placard on a stick. “I grew up with the President! I was his classmate in elementary school! Even as a boy he was the same! On Halloween when all the other children were forced to dress up in costumes and wear masks, Donald stood firm and said, ‘I won’t wear no smelly mask!’” She pulls away a cover sheet from the left side of the placard, revealing a line drawing of the President on the balcony of the White House for his famous “unmasking” moment, his triumph over covid and government tyranny. The MAGA crowd roars with approval and chants, “U-S-A! U-S-A!” The woman glows with the adulation and continues her Halloween hagiography with gusto: “Yes, Little Donald ripped his mask off, unafraid. Even as a child, unafraid!” The crowd is ecstatic. The woman removes the second cover sheet. The people cheer again.

She shouts, “But the smell was not from the confines of the mask! No! Because the face beneath the mask, the boy-man Donald face, puckered with canker, papule, pustule, and malice, was rotten even then!” The mob answers with another chant of “U-S-A!” that breaks in confused disarray mid-cheer as her words and picture sink in. The woman pulls off the third sheet to reveal the true face beneath the mask, a riot of perfidy and narcissistic wound.

“Because beneath the mask is something so rotten, so foul that..!” The MAGAs, slow to the actual meaning of her words, are all the more enraged to be caught in confusion and shame. One of them grabs the woman’s placard and tears it in half, breaks the stick and brings it down on the woman’s head. I run head first into the man and knock him down, just to keep him busy enough to let the woman get to her feet and run away.

She doesn’t run. She grabs the stick and thrusts it at a fat man with a Trump mask. Others descend on us like antibodies attacking a disease. We are outnumbered. I have a lightning bolt behind my eyes: we really aren’t running this show, are we? A boot flies into my side. Another stomps my legs. I’m on my hands and knees, then only hands, then tasting sidewalk.

18: “My God, More Symmetries!”

“Hold still. Your rib’s cracked.” I try to get up and there is no argument. I’m sprawled in the back of the Uber with Felix at the wheel and the woman with the big coat beside him, who has just told me her name is Felice and is glaring at me to lie down.

I lie down. “Felix and Felice. My god, more symmetries.”

Felix says, “Happy accident.”

Felice says, “Happy synchronicity.”

Felix finds me in the mirror. “I told you not to get out back there. Good thing I hung around.”

“Thanks. Are you two in cahoots?”

Felice laughs, “‘Ca-HOOTS! I like that. No pardner, I go it alone.” Felix nods and grunts. He flexes one hand off the wheel. His knuckles are puffy and bruised. She sees them and adds, “But I’m sure glad for the ride.” He nods again. Her eyes are mournful but her mouth is big and shaped for laughs. Up close she must be in her seventies.

Felix turns a hard corner and we’re finally out of the traffic. He eyes Felice. “Just what the hell do you call that thing with your mask rant, anyway? Suicide by MAGA rally?”

I say, “Felix, I gotta go back.”

“You gotta be kidding.”

“I have a job interview at the factory. I really need this job. I’ve got no insurance. No nothing.”

Felice says, “You’ve got a broken rib. And a black eye. And a split lip. And busted glasses. And blood on your jacket. Great for that first impression.”

Felix tilts the mirror so I can see. I look like shit.

“I still have to go back.”

Groans all around. Felix takes the next turn.

Gregg Williard’s work can be found in Conjunctions, Always Crashing, The Rupture, Sweet Lit, Bowery Gothic, JMWW, Bowery Gothic, and elsewhere. He teaches ESL to refugees in Madison, Wisconsin.