George Salis: Your latest Englished work is the hefty novel Journey to the South (translated from the Czech by Andrew Oakland). It features many different locales, stories, and genres. Can you reflect on this polyphony and how it shaped the novel?

Michal Ajvaz: The reason the novel is so polyphonic and polythematic is that it grew out of an absolutely simple beginning. That simple beginning was a feeling of utter emptiness without any shape, any story, figure, or idea. In such an empty nothingness, the infinite multitude of shapes, figures, and ideas is hidden, and as a result, the emptiness can only be expressed by an infinite number of words and images. Of course, a book cannot be infinite in our world, but writing a book whose main topic is nothingness or emptiness will at least have a tendency toward that infinity. I concentrated on that original feeling of nothingness and tried to pull out the images, stories, and ideas hidden in it. This is why my book has so many pages. The image of the tavern by the warm South Sea was the first to emerge, and from that one other images and stories were gradually born.

GS: How would you compare and contrast the Czech language with English? Is there anything you can say for sure is lost and/or gained in the translation of your works?

MA: Czech language says things in more words than English. Since I write long sentences, Czech is probably more appropriate for my way of writing than terse English, but I have no problem with the language of my books taking on a slightly different rhythm in translation.

GS: If you could choose just one of your books to be translated into all languages, which one would you choose and why?

MA: Probably the whole trilogy about traveling which is created by these books: Empty Streets (traveling around a city, means of transport is by tramway), Journey to the South (traveling in Europe, means of transport is by train), The Cities (journey around the world, means of transport is by airplane).

GS: Gabriel García Márquez didn’t take to the term “magical realism” because to him and his people, the magic was as real as anything else in their world. To be more specific, he said, “Surrealism comes from the reality of Latin America.” Is this how you view the magic in your work? Does surrealism come from the reality of your Czech homeland?

MA: I prefer to talk about the area of Central Europe whose Bohemia is a part. Central Europe is roughly identified with the area of the former Habsburg Empire (the Austrians are Central Europeans, but not the Germans, even though they speak the same language), and the “spirit” of this area has features of absurdity, irony, and mistrust of all “great ideas.” In this sense, I think my work has its roots in this Central European atmosphere. And by the way, I do not like the tag “magical realism” used in relation to my work; I do not think it has much in common with the work of writers like Márquez. I feel an affinity with Central European authors like Kafka or Bruno Schulz.

GS: On that note, could you compare and contrast Latin American magical realism with Central European fabulism, if fabulism is the correct word?

MA: I know little about magical realism, but it seems to me that it is rooted in archaic myths and fairy tales. In contrast, Central European grotesque realism is a product of the modern urban environment, with its mystery of enclosed spaces. An important place is the coffee house where people who don’t know each other sit, tell stories and jokes and make up bizarre theories for fun. Magical realism is lyric, while Central European grotesque realism is ironic and rational and contains a great component of humor.

GS: What is a novel you’ve read and think deserves more readers? Why?

MA: Julien Gracq’s The Opposing Shore; Bruno Schulz’s Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass; Giorgio de Chirico’s Hebdomeros; Ernst Jünger’s On the Marble Cliffs. Many people I talk to don’t know these books, even though they are, in my opinion, original masterpieces.

GS: Metal music is often influenced by writers like H.P. Lovecraft or Edgar Allan Poe. It’s not often that entire albums are influenced by writers who fall outside the strict horror/fantasy sphere. One exception includes The Satanic Verses by the black metal band Abazagorath. I recently came across a Czech avant-garde black metal band called Inferno. They named your story, “The Cosmos as Self-Creation,” as a primary influence on their album Paradeigma. Have you heard their music before now? Do you think it does justice to the ideas in your work? Will we be seeing you at any of their concerts in the near future?

MA: The group did not let me know about the album, but I incidentally found it on the net. I listened to the album on YouTube, and it seemed to me that the album’s music has very much in common with my vision of the world as a bundle of different streams of reality. I also saw a video where a member of the group was speaking about taking inspiration from my book, and it seemed to me that the group understood my book properly, even though they emphasized the dark aspects of cosmic reality that in my book are not the only ones. I am not planning to attend their concert, because I am old and lazy.

GS: You’ve written about Borges and his work. There’s no denying that he’s become something of a mythic figure, perhaps even before his death. He’s not only referenced and alluded to in literature but sometimes featured as a character in novels, among other manifestations. What are your thoughts on this? Is this a form of literary sainthood that should be avoided or perhaps encouraged? Would you object to being posthumously mythologized in literature?

MA: Mythologizations are not important. It is not important that drunken tourists in Prague wear T-shirts with portraits of Kafka, the only important thing is Kafka’s—or anybody’s—work.

GS: Speaking of posthumous phenomena. While living in Prague, have you been haunted by Kafka’s ghost at all? In general, how would you characterize the feeling of this city?

MA: As Kafka, in my opinion, is not only the greatest modern author but also somebody who is utterly interesting and important for me as a man; it is a kind of a miracle for me that I walk every day in the same streets as he walked. And by the way, Prague is a relatively small town where everybody knows everybody, and it so happened that my godmother was an aunt of Kafka’s lover Milena Jesenská. Prague was an important center of cultural life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in a time when it was a city of dialogs and fights among three nations (Czechs, Germans, Jews), but it lost a great part of its soul when Nazis expelled or killed the Prague Jews and, after that, Czechs expelled the Prague Germans. But Prague is still a pleasant city to live in. Prague is the setting of my first four books, but then I had a feeling that I had said enough about Prague and began to write about other—real or imaginary—cities.

GS: In the spirit of Calvino’s Invisible Cities and your own The Other City (translated into English by Gerald Turner), which imaginary city would you like to be a resident of if you had to choose? Why?

MA: I admire and love Invisible Cities, and some years ago, I wrote a book named Fifty-Five Cities (Padesát pět měst) that contained a sort of comment to every one of the cities described in Calvino’s book. But I do not dream about living in a non-existent ideal city; I much prefer learning about the spirit and mystery of real cities on Earth. I have learned a lot from cities across four continents and many of them appear in my books.

GS: Could you tell me about an especially influential city you’ve been to outside of Europe?

MA: Probably Tokyo and New York. The first one because I have been interested all my life in Buddhist culture and thinking of the Far East, the second one because NY’s multinational character reminds me of Habsburg’s Vienna—for this reason, it was easy for Kubrick to transpose Arthur Schnitzler’s Viennese novel Traumnovelle (Dream Story) to a New York setting [in Eyes Wide Shut].

GS: The following is a quote from your novel, The Golden Age (translated into English by Andrew Oakland): “When on the island I sometimes imagined an inverse world, in which concert halls would be turned over to the sounds of rain and the rustling of winds while in the treetops and on the weirs and behind the walls of factories, sonatas and symphonies would ring out; in a world such as this the damp on the plastering of walls would probably form coherent text while the pages of books would be covered with indistinct marks.” If we imagined the pages of your books as full of indistinct marks, what would the damp on the plastering of your walls say in their stead?

MA: The damp blots on walls tell every person a story about her personal paradise and personal hell.

GS: You’re no stranger to a cosmic outlook. Considering two extremes, do you think it would be better for humanity if we persisted in our feet-gazing ignorance or if we were constantly faced with the awesome and awful reality of outer space, the stars and planets and black holes that seem to reduce our existence to a speck’s speck?

MA: Regardless of whether we look to the ground or to the stars, we are cosmic creations, we are citizens not only of our country and of the Earth, but of a cosmos as well. Everything that happens on the Earth is a part of the life of the cosmos and bears its mystery.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

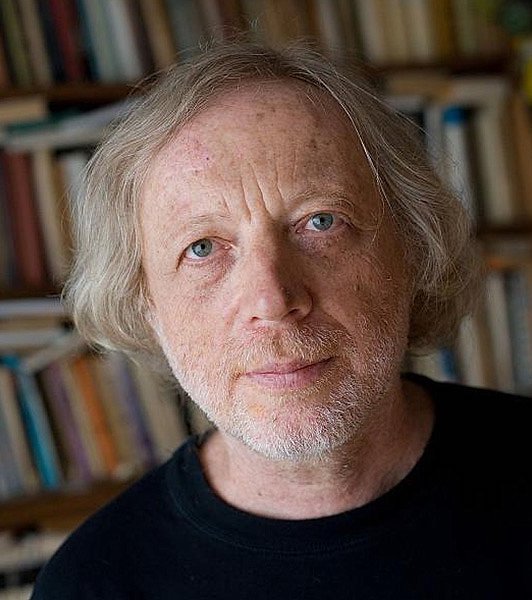

Michal Ajvaz was born in 1949 in Prague. His father was a Crimean Karaim and his mother was an Austrian Czech. He has published eight works of fiction and also an essay on Jacques Derrida, a book about Edmund Husserl’s philosophy, as well as a book-length meditation on Jorge Luis Borges called The Dreams of Grammars, the Glow of Letters, and a philosophical study, Jungle of Light: Meditations on Seeing. He was awarded Jaroslav Seifert’s Prize and the Magnesia Litera Prize. His books of fiction have been published in 24 languages. An English translation of Journey to the South was recently published by Dalkey Archive.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.