George Salis: Your novels One Zero and the Night Controller and The Utopian feature juxtaposing narratives/discourses. Can you reflect on this structure and why you decided to use that instead of, say, a linear story or several or more intertwined stories, as with some of your later novels?

Michael Westlake: In One Zero and the Night Controller, the two narrators—the taxi driver, One Zero, and Angelica, the woman radio-controlling the driver network—perform a duet, each responding, or sometimes failing to respond, to the other. Their voices are radically different: One Zero’s given to verbal play and forays into philosophy and linguistics, loquacious, in need of reassurance; Angelica’s straightforward, practical, extrovert, understanding. Although their alternation is seemingly symmetrical, with each offering a first-person narrative, there is a deeper asymmetry, of mood, character, worldview. Nothing much happens in the novel. Its concern is with the past, and a past they each in their different ways recall as having brought them together as lovers, or possibly not. Each discourse calls into question that of the other. The truth is elusive.

In fact, I have not looked at the novel for more than forty years—it was published in 1980—and while I might be tempted to check the accuracy of my recollections by doing so now, I am prevented by the fact that I am away from home and do not currently have access to the physical book (whose text has never existed in electronic form).

But to return to the question…why did I use this structure rather than a linear story? Partly because in my first (unpublished) novel I’d adopted a conventional first-person narration throughout and wanted to try and move on to something different. I was also interested in French ‘theory’ at the time (Barthes, Lacan, Althusser) and wanted to draw on it in my own writing. It was a heady mix—Marxism and psychoanalysis, in particular—which found an explicit form in The Utopian, once again a ‘double discourse’ novel, but more radically asymmetrical. On the one hand, there is the world of the utopian himself, one Mesmer Partridge, set in a communist matriarchy some 400 years from now and narrated in the third person; on the other, the first person narrative of the psychoanalyst Dr Reed, who is treating Mesmer in the present for his utopian delusions. Their two discourses are radically incompatible—revolutionary vs. high bourgeois—as the two protagonists track each other in their parallel universes. Mesmer has been driven ‘insane’ by the multiple horrors of the world he inhabits in 1979—articulated through three Blue Prints, lengthy lists of instances of injustice and suffering; but Reed, it becomes evident, the upholder of his inequitable world, is the true lunatic.

Originally published by Carcanet Press in 1989, The Utopian was re-issued in 2016 by Verbivoracious Press, with an introduction by Toril Moi and an afterword by Andrew Collier, along with a ‘supplement’ I had written soon after completing the novel itself, but which had not been included in the original publication. In this supplement, I attempted to analyse (psychoanalyse?) the novel itself.

GS: In a 1990 interview with Antony Easthope, you said you got an “obligatory semi-biographical first novel out of the way, unpublished incidentally and it’ll remain so.” What was the title of this novel, and what was the story? Why do you think there’s an obligation for debut novels to heavily feature autobiographical elements? Are you still against publishing it?

MW: It was called Short Change. And I think that’s all I want to say about it. The manuscript was binned a long time ago.

As to whether first novels usually include autobiographical material, I suspect that they do, especially would-be literary novels. Genre novels—historical, crime, sci-fi—are more easily able to escape the prison-house of autobiography. It’s a cliché that one should write about what one knows. And obviously what one knows best (or imagines one knows best) is one’s own life to date (which in the case of young writers is limited to childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood). The trouble with thinly disguised autobiography masquerading as fiction is that it severely limits the scope of what can be written about. In contrast, I believe that one can write about anything at all, whatever excites one’s imagination. The insistence on verisimilitude and ‘authenticity’ limits the scope of what can be written.

GS: Has society gotten any closer to the more progressive elements outlined in your novel The Utopian? Do you think we would be better off under a gynocracy?

MW: If anything, I’d say we’re even further away from it now than at the time I wrote The Utopian. In the 1970s, there were powerful counter-cultural movements and political opposition to the status quo. Now it seems capitalism is the only game in town. As to whether we’d be better off under a gynocracy, experience of the UK’s three female prime ministers, all of them right-wing Tories—Margaret Thatcher, Theresa May, and Liz Truss—suggests not! Simply having women in positions of power does not in itself guarantee that policies will be enacted to redress the wrongs of society. What I envisaged in Mesmer’s Utopia was the radical transformation of all social relations, however idiosyncratic his specific vision may have been. It was a matriarchy, but also a communist one, in which the relations of production had been transformed. The impossibility of specifying a ‘blueprint’ for the future was articulated through Mesmer’s Blue Prints, which had nothing to say about the nature of his dreamed-of society, but listed everything he felt to be wrong about the present world he lived in. Thus, radical negativity rather than utopianism, in the spirit of Marx’s own critique of utopian politics. And indeed, that of the philosopher Karl Popper, whose lectures I attended as an undergraduate at the London School of Economics.

GS: What can you tell me about those Karl Popper lectures? Did they have a significant effect on your views at the time, and how have they changed since then?

MW: I attended Popper’s lectures as part of a joint degree in philosophy and economics. The LSE philosophy department at the time revolved around his thinking in politics (The Open Society and its Enemies) and the methodology of science (The Logic of Scientific Discovery and the later Conjectures and Refutations). Like most of the other philosophy students I emerged from the course a devout Popperian. Though I soon distanced myself from the conservatism of his political thinking, I still believe that his views on science are basically sound. In particular, one neat little logical formulation sticks in my mind: transmission of truth, retransmission of falsity. That is, if the premises are true and the deduction is sound, then the conclusion is necessarily true (whereas true conclusions can be logically derived from false premises—for example, Ptolemaic geocentric astronomy produced accurate predictions of the movements of the planets, even though it was false). Conversely, if a logically derived conclusion (or prediction) is false, then the premise (hypothesis) must also be false. This, in essence, is Popper’s falsification principle.

GS: Would any current events have altered your artistic vision in The Utopian had you written it during these turbulent times? For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic or the Russian invasion of Ukraine?

MW: Undoubtedly Mesmer’s Blue Prints would have included many new instances of human folly and wickedness, among which the reckless burning of fossil fuels would be paramount.

GS: Imaginary Women has an even more complicated structure: three “Thirds,” each consisting of thirteen short units in parallel to each other. From the structure to the wonderful polyphony—“stories, jokes, cinematic references, images, diagrams, quotations, variously drawing upon film and art criticism, film genres, science, mathematics, the I Ching, snooker, poker, superpower relations, Manchester,” etc.—I’m reminded of Gilbert Sorrentino’s Mulligan Stew and Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler. Were either of these novels guiding stars? What were the secret ingredients in the stew of Imaginary Women?

MW: Of the two authors you mention, I’m not familiar with Gilbert Sorrentino. But I’m an admirer of Italo Calvino’s work, especially Invisible Cities, though I did not consciously draw upon it in writing Imaginary Women. Calvino was a leading member of OuLiPo, though at the time I was writing Imaginary Women, I was unaware of its existence and its principles based upon imposed constraints of various kinds. I was, however, thinking along similar lines. In Imaginary Women the constraining system you refer to (the three Thirds, depicted diagrammatically at the start of the novel), through repetitions and parallels in the thirteen ‘steps’ of each Third provided an overall architecture to work within. The artificial constraint of the three-part tiered structure gives coherence to the multiple ‘voices’ and characters populating the novel, among them the independent filmmaker Mac**ash, who lives in and works from the Fur Q vehicle. From the outset, as related by her cat Adolphus, she is caught up in a noirish plot (in which readers may spot various film references, including The Maltese Falcon).

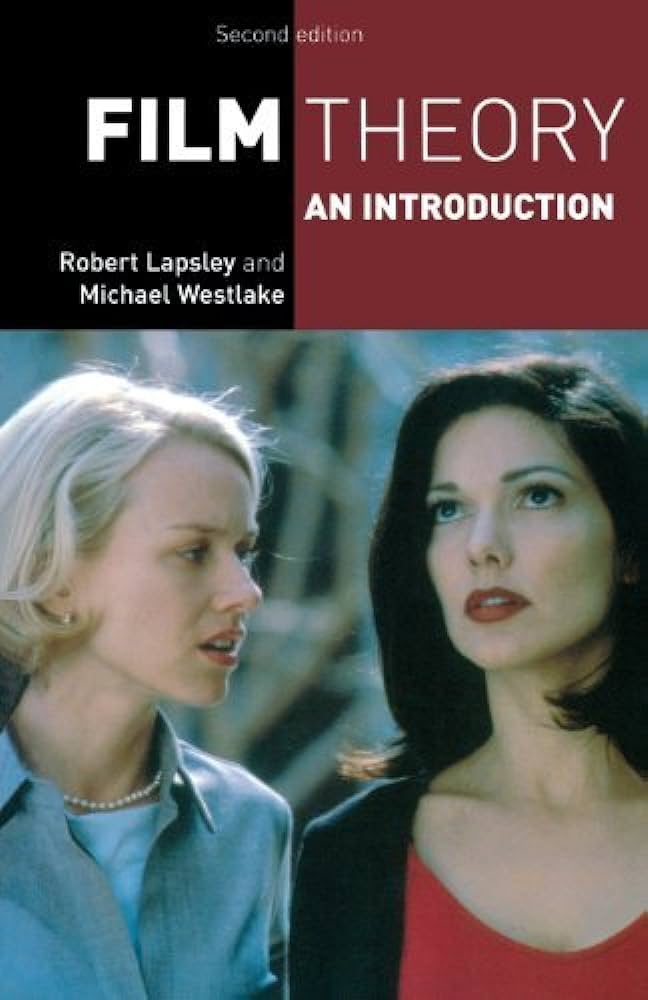

I should say at this point that all of my novels have their specific focus, their ‘aboutness’—in One Zero it was language and memory, in The Utopian revolutionary politics and psychoanalysis, and in Imaginary Women it was cinema. At the time I wrote Imaginary Women I was living in Manchester, where I was involved in a number of film-related activities, including teaching film studies at Manchester University, chairing Northwest Arts film panel, and working as a freelance journalist and film reviewer. It was during this period in the 1980s that I was also working with my co-author Robert Lapsley on Film Theory: An Introduction. So Imaginary Women can be seen as a ‘wild’ counterpart to a sober, carefully researched academic text. I should also add that Imaginary Women is my ‘Manchester novel’ (joining the illustrious company of Elizabeth Gaskell and Anthony Burgess). At the time, before the fall of the Soviet Union, Manchester was twinned with Leningrad (now once again Saint Petersburg), and the parallels with its twin can be detected in my novel, not least through the theme of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD).

GS: Your three subsequent novels are 51 Sōkō to the Islands on the Other Side of the World, The Triumph of Love and Other Paintings, and World Enough. How do you view these works in terms of your artistic development, and how do they fit into your oeuvre in general?

MW: Firstly, I’d like to say something about how Imaginary Women and the first two of these three subsequent novels were linked to the places I was living in at the time of writing them. I’ve already said that Imaginary Women was my ‘Manchester novel’ in the sense that it was set in (an unnamed) Manchester and ‘the hills to the east our city’ (the Pennines). But I would not and could not have written it had I not been living there and actively involved in its cultural, artistic, and intellectual life. I drew on my varied experience of the city, not in order to reproduce it but to use it as raw material to be creatively reworked to produce a Manchester that was as imaginary as it was real(istic).

In the late 1980s, I left Manchester and moved to St Ives in the far west of Cornwall, where I lived for two years. I had conceived of 51 Soko as a novel that would look at the United Kingdom through radically other eyes, namely four Japanese writers of letters (the soko of the title) addressed to a motley collection of individuals (real and fictional, living and dead, singular and plural) in these islands on the other side of the world. When I arrived in St Ives I knew it had been home to a group of artists (including Barbara Hepworth—one of the addressees of the soko—Ben Nicholson, Patrick Heron, and, briefly, Mark Rothko—a painting by whom would figure in my next novel), but I had no idea that it had any connection with Japan. To my surprise, I discovered that the potter Bernard Leach—another soko addressee—had lived and worked in Japan before settling in St Ives. Not only that, but he had donated a collection of writings on Japan to the local library, which proved to be a valuable and rather offbeat resource for me. I also discovered that Virginia Woolf—yet another soko addressee—had lived for a while in St Ives and that Godrevy lighthouse, just up the coast from the town, had been the model for the Hebridean lighthouse in To The Lighthouse. But as well as providing me with some soko addressees and Japan-related material, St Ives was conducive to the creation of a certain mood. I felt I was on the very edge of the British Isles, ‘othered’ by its peripherality and by the wild rocky scenery of the coastline and the great storms that would blow in from the Atlantic.

I started writing And Other Paintings (its original title, modified at the suggestion of my editor at St. Martin’s Press) soon after my arrival in Paris in 1990. And in this case the linkage between the novel and the place I wrote it in was immediate and direct: I spent some three weeks wandering through Paris’s public art museums in search of the thirteen paintings that would be the novel’s collective narrator. I had no preconceived ideas of what I was looking for. It was as if the paintings found me. At the end of this time I had my corpus and could start writing the story it wanted to relate.

Moving on to the question of how I view the novels that followed Imaginary Women in terms of my artistic development, I’d say they developed and refined the process of creating a constraining architecture within which to write. In 51 Soko, as in Imaginary Women, this was explicitly presented at the outset, although with two superimposed structures rather than one. The four soko writers thereby distributed over the 51 components of the text each have their own voice, style, status, preference for addressees, interests, and ontological status. Prince Genji, for example, the protagonist of Murasaki Shikibu’s classic The Tale of Genji, exists only when being read about. He writes only to women, among them four Barbaras (Hepworth, Cartland, Windsor—a comedy actor best known for her roles in the Carry On films whom Genji imagines to have royal status—and Castle, a Labour politician, to whom Genji would have written sooner had he known she was “a person, not a building”). Mishima/Oshima, who writes only to couples, is an uneasy alliance of the writer and the filmmaker within the persona of a motorcycle production line worker. The resulting scope for bias, misattribution, and incomprehension generates a vision of the United Kingdom that is both bizarre and perhaps more truthful than straightforward naturalism or reportage. Mirroring the Japanese archipelago, these islands on the other side of the world emerge as a montage (or bricolage) of disparate elements.

The Triumph of Love and Other Paintings is, I consider, the most accomplished of my novels. It is certainly the most light-hearted, even joyful. Its premise is that early in the story told by the thirteen paintings it appears that one of them is a fake (since one of the protagonists of the story has inherited a painting that purports to be the original of one of the thirteen). But which one? As the narration shifts from one painting to the next—all of them are reproduced in the front and back endpapers—each in turn is naturally insistent that it is genuine. The collective endeavour to find the impostor becomes an exercise in passing the buck, while individually each painting seeks to inflect the narration in such a way as to make the characters in the story reveal the identity of the fake. At the same time the story has its own momentum that escapes the attempted control of the pictorial narrator. Thus And Other Paintings is, among other things, a playful meditation on the relation between author and text, perhaps especially relevant in my case in that I don’t plot in advance but allow the constraining structure to yield what it may. In other words, I don’t know where my novels will lead me. And Other Paintings is also a semi-serious interrogation of the relations between art, authentication, and value (both aesthetic and, especially, financial). And, not least, it is a happy-ending romantic comedy set in Paris.

GS: Your next novel, World Enough, appeared in 2005, several years after And Other Paintings. What accounted for this longer gap between publications than with your previous work?

MW: Two reasons. The first because of the scale of the novel, which I’d originally conceived as a duology, to be titled World and Time, with reference to Andrew Marvell’s poem. I later decided to make it a single volume, but this was still much longer than anything else I had written, especially its first version, which I then substantially reduced for the second and final version. The other reason was institutional, in that after unsuccessfully seeking a regular print publisher, I eventually turned to self-publication with the internet publisher Lulu.

GS: I’ve had a couple of nightmare experiences with publishers, so I can certainly see the appeal of self-publishing, including the freedom to design the book according to one’s vision. There are disadvantages, of course, such as the responsibility of having to market it among oceans of other books, etc. What can you tell me about your experiences with self-publishing? Do you think it has been ultimately the best choice for your work, or would you prefer a traditional publisher?

MW: Given the difficulty these days of finding a traditional publisher for non-mainstream work, I think that self-publishing is a good alternative, despite the financial outlay involved, since at the very least it ensures that one’s work is available, either as an e-book or through print-on-demand. I have been very pleased with the quality of Lulu’s production, both for World Enough and for my later One Zero sequel. Given the changes in the business model of the publishing industry, I would recommend considering self-publication, especially for less obviously commercial work.

GS: Did you continue your use of structuring constraints in writing World Enough? And if so, how did its architecture shape the narrative?

MW: In the first version, I explicitly used the constraint of concatenated pairs of categories. The thirteen categories, non-identically paired with the remaining twelve categories, generated 78 chapters, starting journeys-science, science-games, games-hotels, hotels-music…through to Africa-games, games-devotion, devotion-journeys, thus completing the cycle. Rather like the process of selecting the thirteen paintings for And Other Paintings, these various categories seemed to come to me out of nowhere. It was not a conscious process of sifting through possible candidates and choosing the thirteen from among them, but was comparable to free association in psychoanalysis, whatever came to mind. In contrast, a second structuring layer involved carefully constructing the four central characters of the novel, whose narrating voices were distributed throughout the 78 chapters on the basis of a second algorithm. In each chapter the specific pair of categories—explicit in the chapter heading—imposed itself upon and shaped the content of that chapter. Thus in chapter 22, blood-anomalies, these two categories in some measure determine what it is about. Of the thirteen categories, ‘anomalies’ has the specific role of generating the alternative history that constitutes the world of World Enough. Paired with ‘Africa,’ for instance, it makes the USA the United States of Africa, while North America remains colonised by various European powers. In anomalies-journeys, Lenin’s sealed train from Switzerland to Petrograd in 1917 is derailed and the Bolshevik revolution never happens (but Stalin nevertheless becomes head of state in a tyrannical capitalist Russia). And so on, for the remaining pairings with anomalies.

At this stage, having completed the 78 chapters, I had no intention of going any further. But on reflection, I decided that it would be better if the constraining architecture—the 78 paired categories—were hidden. So I then extensively rewrote the text, making no mention of the pairings or indeed of the categories at all, reducing it in length by about a third, and re-ordering the sequence of events. The resulting novel is broadly chronological—interspersed with flashbacks and flashforwards—tracing the interacting lives of the four main characters—the Russian sisters Katerina and Padua, and two African men, Quaque and Million M’loy—from the early 20th century through to an indeterminate time in the 21st century. Each of them has their own distinctive narrative/narrational style (in an echo of 51 Soko) that defines them as much as anything they say or do. Quaque’s narration, for example, is convoluted and complex, drawing on multiple verb tenses, especially during his analysis by one Dr Poisson in the apocalyptic post-revolutionary Paris of the 1970s. Padua’s is elliptical and fractal, foreshadowing the tragedy that befalls her. M’loy speaks as he feels, tough, brusque, hardboiled, while Katerina’s discourse is a model of measured reason.

Having finally completed World Enough, I felt exhausted and written out (and indeed had succumbed to an agonising bout of shingles during a year spent isolated in rural Normandy eliciting the fourth and most elusive voice, that of Padua).

GS: You mentioned in the previously cited 1990 interview that your debut novel had too little structure and it wouldn’t be something you’d write now. That first novel, One Zero and the Night Controller, came out in 1980. Fast forward about 40 years later and you wrote a sequel to it, One Zero and the Ontological Question. I’m fascinated by the act of revisiting a work after so much time. The same thing happened with Ray Bradbury (Dandelion Wine [1957], Farewell Summer [2006]) and Robert Coover (The Origin of the Brunists [1967], The Brunist Day of Wrath [2014]). How did a sequel come about, and what was it like revisiting that world through a new lens? Earlier in the interview, you said you hadn’t looked at your first novel in over 40 years. Did you not crack it open at all when writing the sequel?

MW: This sequel to the original One Zero novel was not something I’d planned on doing. In fact, I’d rather assumed that World Enough would be my last novel and indeed several years passed after completing it during which I wrote no further fiction. But having stopped off in Bangkok on my return from a trip to Australia, I felt I wanted to get to know Thailand better. I have since visited the country often, usually during the European winter (for obvious climatic reasons), and have spent a considerable amount of time in Bangkok. I think it was from the experience of taking taxis, through Bangkok’s seemingly perpetual traffic jam, that I envisaged One Zero—now much older and perhaps a little wiser—working as a cabbie there. This initial idea of transplanting him from London to Bangkok somehow made it possible to address a philosophical question—that of the novel’s title—which had long fascinated me, along with, it turned out, other philosophical themes too. There was no need to return to the original One Zero novel, partly because the setting was entirely new and partly because I was able to re-find One Zero’s ‘voice’ without difficulty.

The novel opens, before One Zero’s first-person narration, with a Prelude that, chapter by chapter, encapsulates in bullet-pointed headings, subheadings, subsubheadings, etc., the various philosophical questions encountered in One Zero’s quest. Thus, with reference to chapter 34:

34.1.3. This universe, at least, is such that it can interrogate its own nature and origins, one self-reflexive universe amidst the possible infinity of self-reflexive universes.

34.1.4.1. The wager is that the phenomenological singularities of the thesis map and are mapped by the physical singularities of the antithesis, semantically, conceptually and mathematically—even if the mathematics has yet to be devised and/or discovered—producing an ontico-ontological totality that is dynamic, never-ending, indestructible and alive.

The narrative itself opens with One Zero being tasked by a customer, on behalf of her daughter Apple, to find the answer to the question of why there is something rather than nothing.“Consider me hired,” One Zero tells her. In contrast to the formalistic precision of the Prelude, the narrative is a boisterous mix of genres, events, characters (including the ladyboy Silky, a mysterious Hollywood location scout, a horticultural monk, the sinister agents Pink and Orange, and a succession of passengers in One Zero’s cab) and Thai locations (Chiang Mai, Pattaya, and a village in Isaan, Thailand’s vast rice-growing northeast). It also contains a succession of lists compiled by One Zero in support of his belief that lists and stories cover everything that can be said about the world. Another feature of the novel is its comprehensive index, running to fifteen double-column pages, which unlike a conventional index precedes and leaves open the final chapter. For instance, with reference to the multiple and uncontrollable personae of One Zero’s satnav, the index entry is:

satnav, passim

bahtnav, 147-49, 151, 162, 264

batnav, 7, 9, 10, 26, 146, 157, 264

bratnav, 7, 23, 157, 264

caveatnav, 263-67, 304

chatnav, 8, 110-114, 124, 157, 264

diktatnav, 183-85, 187-88, 192, 201, 205, 256, 264

dratnav, 7

expatnav, 205-08, 211, 264

fermatnav, 200-02, 210, 264

gnatnav, 7, 80-81

hatnav, 157

hellcatnav, 239-241, 243, 244, 250, 264

howzat!nav, 180, 183, 196, 205

matnav, 157

patnav, 10

polecatnav, 238-39, 241, 243, 264

pratnav, 7

ratnav, 7, 56-57, 62, 63, 64, 157, 253, 264

splatnav, 7

spratnav, 157

squatnav, 157

tomcatnav, 238-39, 241, 243, 244, 264

twatnav, 18, 87-88, 90, 157, 264

watnav, 39, 124, 264

wildcatnav, 238-40, 241, 242-44, 264

GS: You’re currently visiting Thailand, the setting of One Zero and the Ontological Question. What calls you to Thailand and what can you tell me about some of your experiences there? How would you compare it to the UK, for instance?

MW: I broadly divide my time between Scotland—my country of residence—France, and Thailand. Each has its attractions, each is very different from the other two, and I have friends in all three. One of the things that give Thailand its distinctive character—along with its geography, climate, and Buddhism—is that, unlike all other countries in Southeast Asia, it was never colonised and I think this is reflected in the demeanour of Its people: confident, at ease, friendly. Having spent my childhood in hotels—my parents were hotel managers —I find that passing a few weeks each year in hotels in different parts of Thailand is at once relaxing and creatively invigorating.

GS: What is a novel you’ve read and think deserves more readers? Why?

MW: I’m not sure ‘read’ is the right word, but one that comes to mind is Christine Brooke-Rose’s Thru, an extraordinary compendium of graphic and textual figures that has been called “one of the quintessential texts of postmodernism.” Brooke-Rose wrote it when she was living and teaching in Paris in the 1970s, and it is very much a novel of that era. Another ground-breaking work from the same period, which has had more visibility than Thru, is Georges Perec’s La Vie Mode d’Emploi (translated as Life A User’s Manual).

I should add, however, that my reading extends way beyond so-called postmodern or experimental fiction. While I may choose to write non-mainstream novels, my reading preferences are far wider. In general, I read for pleasure and relaxation rather than for intellectual stimulation. Hence crime fiction, say. Or espionage, of which one brilliant exponent I have recently been reading is Mick Herron, with his Slough House series. Quality may be found in all genres, irrespective of their status.

GS: You’ve worked as a French translator. What are your favorite French books, and which would you love to translate into English if given the opportunity?

MW: Yes, I have worked, and indeed still work, as a French translator (mostly of academic articles for publication in English-language journals in various fields), but not as a literary translator. As for French books I particularly like, and might have been interested in translating were my French up to it, I’ve already mentioned Perec’s Life: a User’s Manual, which I read in parallel in French and English. Then there is Proust’s massive A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, which I’m forever somewhere in the midst of and return to from time to time, again reading it simultaneously in French and English (Scott Moncrieff’s translation, whose title Remembrance of Things Past I consider captures the underlying feel of Proust’s title better than the more literal, and recent, translation of it as In Search of Lost Time). I also like Georges Simenon.

GS: You’ve also written a book on film theory with Robert Lapsley, simply titled Film Theory: An Introduction. What is your most surprising opinion or theory regarding a film?

MW: Film Theory was written for film and media studies students, and was precisely an introduction to the field as it stood then, with chapters on auteurism, politics, psychoanalysis, narrative, realism, and the avant-garde. It was later re-issued in a second addition with a lengthy afterword to address the thorny issue of postmodernism. As an introduction to the field, it did not attempt to put forward any original ideas, but simply to provide a comprehensive survey of the state of the art.

As for my opinions about particular films, I’d say they’re fairly conventional. Like most regular film-goers, I have my favourites, some of which I have watched multiple times. These would include Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, Polanski’s Chinatown, Hawkes’s Rio Bravo, and Arthur Penn’s Night Moves. Also Touch of Evil, which I think is Welles’s finest film. Then, having spent more than twenty years living in France, I am unsurprisingly a big fan of French cinema: Godard, Marguerite Duras (India Song), Rivette (Céline and Julie Go Boating), Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Claire Denis…. More recently, I much enjoyed the cinephile TV series Call My Agent. Then there is, of course, the Spanish-Mexican director Luis Buñuel whose later films were produced in France and in French, and whose oeuvre includes such gems as The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Milky Way and of course the unforgettable (and for its opening scene, shocking) Un Chien Andalou. Italian cinema also figures very much in my personal filmography: directors such as Fellini, Visconti, Bertolucci, and (on a good day) Antonioni. I also like Asian cinema, particularly Iranian, Korean, and Japanese (the recent Drive My Car was a delight). I think it is important and healthy to watch as much non-English language cinema as possible, subtitled, of course, not dubbed. Film, more so than any other medium, even literature (where, apart from French, I for one am obliged to read it in translation), is able to convey the complexity and richness and difference of other cultures. The hegemony of Hollywood tends to obscure the fact that America is not only one culture among many, but is in certain respects an outlier culture.

GS: Have you kept up with recent films? What do you think about the state of modern cinema?

MW: I am fortunate that the small Scottish town I live in has—thanks to the EU before the UK’s self-harming Brexit—a state-of-the-art 40-seater cinema that screens a mix of mainstream and art-house product. And whenever I’m in Paris, I take advantage of its unmatched provision of cinematic screenings (with some 300 films every week). Otherwise, I make do with streaming (on my laptop) or watching DVDs, though I’m conscious that doing so falls far short of the experience of seeing a film in a cinematic venue.

As to your question about my view of modern cinema, to some extent that depends on how recently we are talking about. In terms of Hollywood, a number of major directors are still producing films, even if their best work dates back to before the turn of the century. I’m thinking in particular of Quentin Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs, Jackie Brown, Pulp Fiction thumbs up, Kill Bill thumbs down, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, not sure), David Lynch (Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive yes, Inland Empire no) and, to keep it brief, Paul Schrader (whose The Card Counter I recently saw and enjoyed in the context of a Schrader season at a Paris cinema). Mostly though, rather than thinking in terms of directors, I simply go to see movies that look interesting. For example, Tár, or the British film Aftersun, or The Banshees of Inisherin, a dark film that was misleadingly publicised as a comedy.

GS: Considering your love of film, have you ever thought about getting into filmmaking?

MW: The closest I’ve ever got to the production side of cinema was writing a screenplay. Co-written with a friend who had for a while been a film actress, it was a romantic comedy based on time travel, with the heroine from present-day London and the hero from New York a hundred years previously. We submitted it to my US agent, who “didn’t love it.” Some months later Kate and Leopold was released. We were not inclined to go and see it.

GS: While we’re on sweeping topics, what do you think about the state of modern literature?

MW: Regarding the state of modern literature, I honestly don’t know. On a recent long-haul flight I seemed to be the only passenger actually reading a book, though others may have been doing so on Kindles. Yet I believe that book sales are holding up in the face of digital media. And I have in recent years discovered new authors who are producing interesting and original work. To cite two in particular, Nicola Upson’s take on the inter-war crime writer Josephine Tey gives a new twist to the crime fiction genre, and China Miéville’s remarkable Embassytown and Kraken are at once page-turners and intellectually demanding. Like most readers, perhaps, I rely not only on reviews to find new titles and authors, but also on word-of-mouth and personal recommendations. In this regard, The Collidescope website looks like a promising resource for encountering work that I would not otherwise have been aware of.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Michael Westlake’s seven published novels include Imaginary Women (Carcanet Press, Manchester, 1987), 51 Sōkō to the Islands on the Other Side of the World (Polygon Press, Edinburgh, 1990), The Triumph of Love and Other Paintings (St Martin’s Press, New York, 1997), World Enough (Lulu Publishing, 2009), and One Zero and the Ontological Question (Lulu Publishing 2019). Born in southern England during World War II, he has lived and worked in various countries, including the United States (during the 1960s) and France (from 1990 until 2012, when he moved to the Scottish Highlands, his current place of residence).

Apart from writing fiction, Michael has worked as a taxi driver (drawn on for his two One Zero novels), journalist, advertising copywriter, maths tutor, and, currently, translator (from French to English). He has also had spells in academia, in particular at Manchester University, where he taught film studies (and co-authored Film Theory: An Introduction). His writings reflect these peregrinations.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.