George Salis: What was the initial shiver of inspiration behind your new novel, The Suicide Museum?

Ariel Dorfman: A shiver does not really denote how my process of creation occurs. Meteorological metaphors or sea-faring ones might be more appropriate. Ideas come to me like a tide or clouds beginning to form on the horizon. I had been toying for many years with the question of whether Salvador Allende had committed suicide or been murdered during the September 11th coup in Chile, along with many other threads that find their way into the novel: the Jewish children who were hidden during the Nazi occupation of Holland, how to awaken humanity to the danger of our extinction, the problems of transitions from dictatorship to democracy. None of these obsessions can become narrative material until I can figure out who tells the story and how they are embodied in characters with their own secrets and dilemmas. This novel began to come together when I wondered whether I dared to make the storyteller someone who was just like me, who bears my name and has my friends and family and chronology, and use that to investigate Allende’s death.

GS: What research did you conduct when writing The Suicide Museum? Also, how did you find the balance between the fictional and the historical?

AD: There is no balance. There is a merging between what is historical and what is fictional, so the reader is constantly challenged to ask what the limits of reality are, how we can remain ethical and centered if the past is up for grabs, constantly shifting with each person who remembers, each person who interprets that past differently. This literary strategy allows a book that deals with many serious subjects (military coups, exile, climate apocalypse) within a playful experience, a ride that readers can enjoy. As to research, not too much, as I knew so much already about what I was writing. But I did make a point of reading every book about Allende and especially the differing versions of his death that are available. And lots on climate change and plastics.

GS: What is it about Argentina and other Latin American countries that breed such beautiful and imaginative magical realist novels?

AD: I have always been wary of the term “magical realist,” which does not characterize my work nor that of most Latin American authors. The term implies that this is a “style,” something that can be imitated (and mediocre writers do imitate it and may even get away by doing so), almost a marketing ploy. I prefer the term “lo real maravilloso,” the real that is marvelous, a term coined by Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier, basically signifying (forgive the inevitable simplification) that the people of our lands compensate through their imagination for the terrible weight of oppression and their supposed insignificance by creating alternative universes that are so much richer than the drabness offered to them and us by those societies. Please note also that there is a long tradition of fantastical literature in Latin America and particularly in Argentina that is often awkwardly subsumed in the all-encompassing term “magical realist.” I could list dozens of extraordinary writers who don’t fit into that category but one will suffice, and he is among the greatest of the 20th century: Julio Cortázar.

GS: You’ve lived in North Carolina since 1985. What can you tell me about your experiences in this state and how it compares to Argentina and Chile? Is there a different kind of magic there that initially attracted you?

AD: North Carolina has been a haven for me and my family, giving us refuge and a base when we most needed it—and we were fortunate to be able to return there once a crisis, as described in The Suicide Museum, forced us to emigrate yet again from the Chile to which we had returned, presumably forever, back in 1990. But my experience of North Carolina has not been really deep, despite having devoured, in my youth, Southern literature (Faulkner, who is a mainstay for all Latin Americans, our North Carolinian genius Thomas Wolfe, Tennessee Williams, Alice Walker, Flannery O’Connor, and so many others). I have only one short story set in my hometown of Durham. “Fair Trade” (published in 2018 in The Bare Life Review) is inspired by what I have observed among the newest Latino arrivals to what my eldest son Rodrigo has called el Nuevo South in his documentaries and his memoir Generation Exile: the Lives I Leave Behind (Arte Publico Press, 2023), but it is the Deep South of Latin America where my mind really resides.

GS: Your latest novels, such as The Suicide Museum and Darwin’s Ghosts, were originally written in English. Can you talk about the transition from writing in Spanish to English and the decision behind that, or do you still write your manuscripts in Spanish first?

AD: The relationship between my English and my Spanish is far too complex to summarize in a few lines. I have written two memoirs about this back and forth during my whole life and also innumerable essays (I’d recommend “Footnotes to a Double Life” in Wendy Lesser’s anthology of writings from 15 bilingual authors, The Genius of Language: Fifteen Writers Reflect on Their Mother Tongue, Penguin, 2005). But at this moment, I have come to a compromise, maybe a truce, between my two linguistic loves: when I write something in one language, I immediately start a version in the other one, a process facilitated by the fact that when I work first in English, for instance, as in the case of The Suicide Museum, the Spanish is already present inside me, guiding choices, rhythms, vocabulary, inspiring me from a tradition where Quevedo or Cervantes or Gabriela Mistral are part of my vision and approach. The same happens when I write first in Spanish (as in my op-eds for El País or certain poems and stories and plays): my English-language self is vigilant and murmuring alternatives.

GS: Death and the Maiden is considered a classic. Can you reflect on what moved you to write this play? Do you think it’s developed a deeper resonance considering the crimes of torture at Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay, etc.?

AD: In The Suicide Museum, I go into this with great detail, so I would be doing a disservice to both the play and my novel to repeat in abbreviated form my painful exploration of the origins of Death and the Maiden and how it is born out of the twister transition to democracy in Chile in 1990. As to its resonance, alas, it continues to be relevant. But, of course, that play is much more than a journey into atrocity and its eternal aftermath. It probes trust, memory, love, betrayal, the empowerment of women, and how the public and the private intersect and entangle one another, so it has a significance beyond the pain one human being can inflict upon another.

GS: Death and the Maiden was adapted into a film by Roman Polanski, and it starred Sigourney Weaver and Ben Kingsley. If you could choose any, what other work of yours would you like to see adapted into a film? Why?

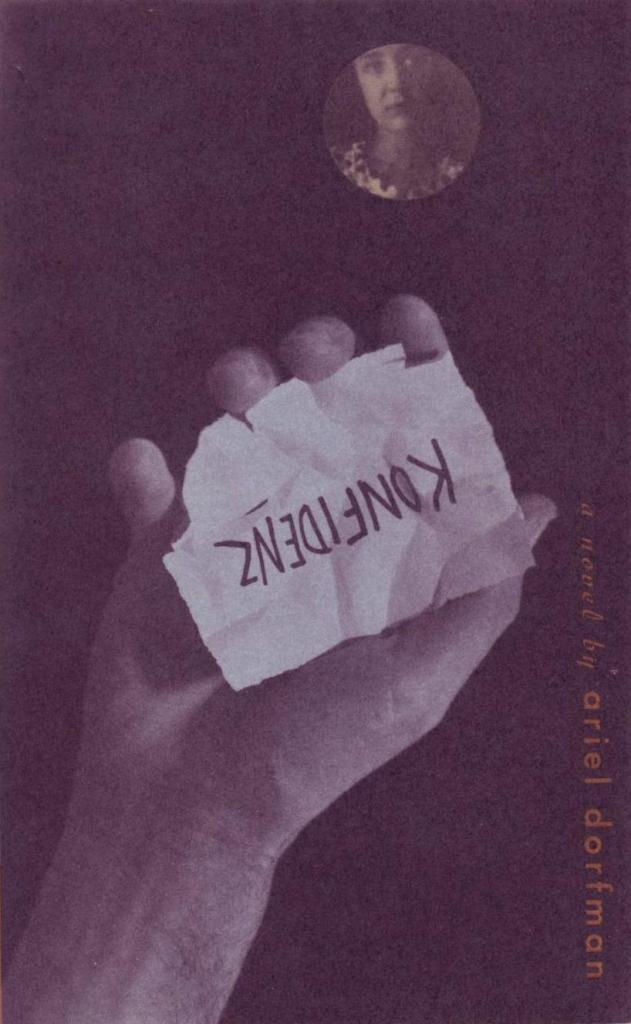

AD: A few years ago I would have chosen my novel Konfidenz and my children’s story, The Rabbits’ Rebellion, but they are both well on their way to being filmed, so I’d rather concentrate on some other possibilities. One is Blake’s Therapy, my novel about a millionaire who is given voyeuristic possession of a Latino family so he can cure himself of a malady of guilt that is assailing him. I’ve written, with my eldest son Rodrigo, a screenplay that was commissioned by Salma Hayek some years ago and has languished without being produced, so that would be my number one recommendation. But there is also another novel, Allegro, coming out next year, narrated by Mozart as he seeks to unravel the mystery behind the deaths of Bach and Handel—I’d love to see a film version that would rescue Mozart from the idiotic way he is portrayed in Amadeus (Salieri is a terrific character but our Wolfgang is denigrated and defamed and deserves a better fate, which I hope I have offered him). And, of course, as you are aware, there are two major stories nestled within The Suicide Museum that have cinematic promise. One is about a wedding photographer whose clairvoyance about the couples he is working with before their marriage lands him in a lot of trouble when he falls in love with a bride. The other deals with a detective who, having sought asylum in an Embassy after a coup, now has to solve a series of murders inside those premises.

GS: What’s a novel you’ve read and think deserves more readers? Why?

AD: Let me suggest two. One is The Other Hand by Deena Metzger, one of the most mesmerizing and lyrical books about evil and redemption I have ever read (she has also written wondrously about the human-animal relationship). The other is Apeirogon by Colum McCann, which, though it has received excellent reviews, has not, in my opinion, been sufficiently recognized as a breathtaking experiment and one of the most compassionate books I have read in years. The two protagonist fathers—one Israeli, the other Palestinian—offer a model for how peace can be achieved not only in those troubled lands but across our imperiled planet.

GS: What do you imagine the unborn fetuses from The Last Song of Manuel Sendero would think of the world as it is today?

AD: They would repeat their demands that must be met if they are to call off the strike they have organized until adults make the world worthy of them. First: get rid of weapons that can cause massive death. Second: Instead of freedom of prices, freedom of food must be declared. Third: Everybody has to take off their clothes. Basically: end war, end hunger, end hiding who we are. And they will refuse to be born until those conditions are met.

GS: Do you think anti-natalism is a reasonable position considering our shaky present and bleak future, or do you have more hope than I do?

AD: I wrote that novel back in 1980. My position now is spelled out in The Suicide Museum, but I would do a disservice to the reader to explain how the investigation into the death of Allende and the way in which humanity is committing suicide reveal a model of what we must do if we are to survive. Today, as apocalypse nears—a theme I approached in my recent sci-fi novella, The Compensation Bureau—I fear the world is not yet ready to listen to the unborn who are demanding that we do something now before they even have a chance of seeing the light of day and the wonder of night.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Born in Buenos Aires on May 6, 1942, Ariel Dorfman is an Argentine-Chilean-American novelist, playwright, essayist, academic, and human rights activist. He is the author of numerous works of fiction, plays, operas, musicals, poems, journalism and essays in both Spanish and English. His latest work is The Suicide Museum. Learn more about him and his work here.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.