George Salis: I’m interested in your perspective on Dalkey Archive’s history and the aftermath of its many writers. I’ve discussed this with REYoung on my podcast, and he said that DA was partly run like a “Ponzi scheme.” If you’ll indulge me, I’d also like to hear about your relationship with John O’Brien, especially after coming across this in one of your blog posts: “I will not repeat the whole depressing and sad story of my relationship with the founder and owner of Dalkey Archive Press as John O’Brien sadly drank himself to death and left a major publishing enterprise to its fate. O’Brien was even godfather to my daughter Elizabeth.”

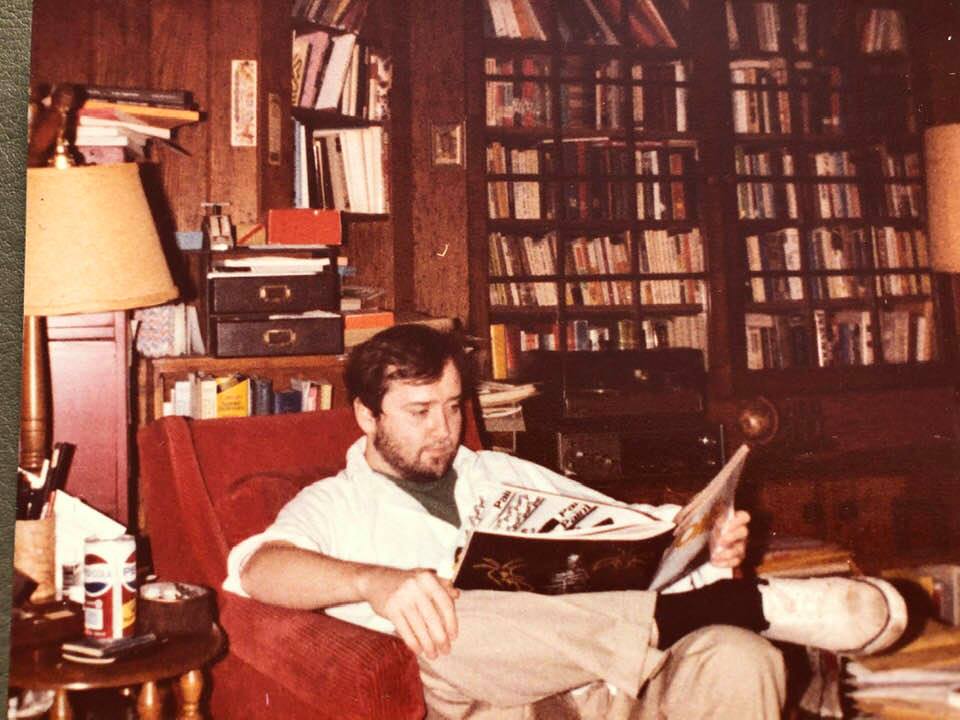

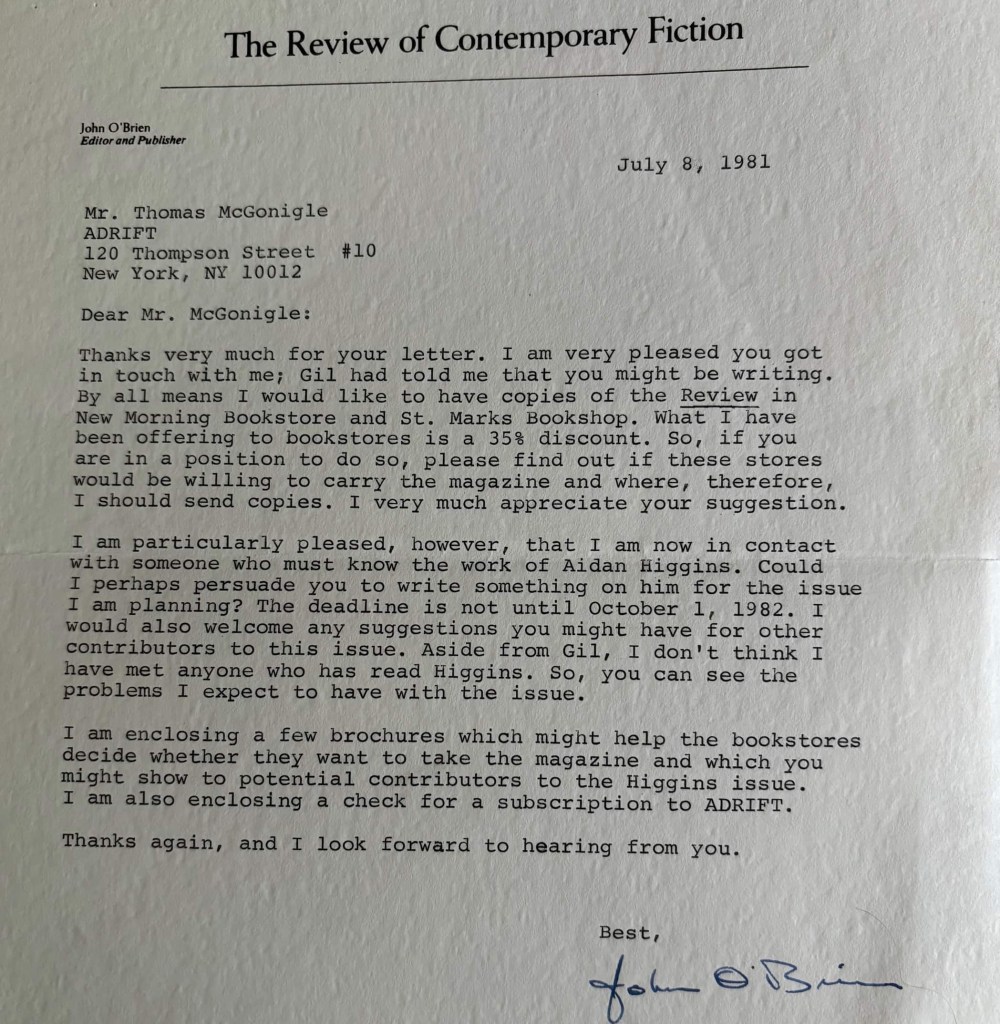

Thomas McGonigle: I came to John O’Brien via Cadenza, the novel by Ralph Cusack, which, in the summer of 1981, Gilbert Sorrentino mentioned in the New York Times Book Review that he would be reading. [The first letter from John O’Brien is dated July 8, 1981 (see below)] I wrote a note to Sorrentino about this novel, which I had learned about in Grogan’s pub in Dublin, and Sorrentino sent me to O’Brien, who had just started the Review of Contemporary Fiction. In the third issue of the journal, I was writing a round-up review including Thomas Bernhard, Juan Carlos Onetti, B.S. Johnson, Stanley Crawford, Osman Lins, Francis Stuart, and Gregor Von Rezzori. The issue was devoted to Douglas Woolf and Wallace Markfield. He also included an essay by Shklovsky on Andrei Bely, an excerpt from a new novel by Kenneth Tindall, and two prepared slides from my St. Patrick’s Day, Dublin 1974…it would take more than 30 years for my novel to appear, now called St. Patrick’s Day: Another Day in Dublin.

But you can see from the range of authors mentioned later on that from the beginning, the review and Dalkey Archive would be unlike the vast junkyard of American publishing, which it was then and continues to be. Dalkey Archive was modeled on the original New Directions and the early Grove Press. I was happy to see two of my novels in the same company as books from Douglas Woolf, Aidan Higgins, Desmond Hogan, Claude Simon, Robert Pinget, Luisa Valenzuela, Georgi Gospodinov, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Flann O’Brien, Nicholas Mosley, and I must not forget two books that only Dalkey Archive would think as essential: Fragment of Lichtenberg by Pierre Senges and November by Christopher Woodall which is only 725 pages long….

I just discovered that an early Dalkey Archive novel, The Great Fire of London by Jacques Roubaud, sells for $63. Another lost book from the early years before the press’ founder launched himself on a sure voyage to self-destruction—there are so many Dalkey books that will simply disappear into the abyss as the new proprietors are dutiful but not visionary….

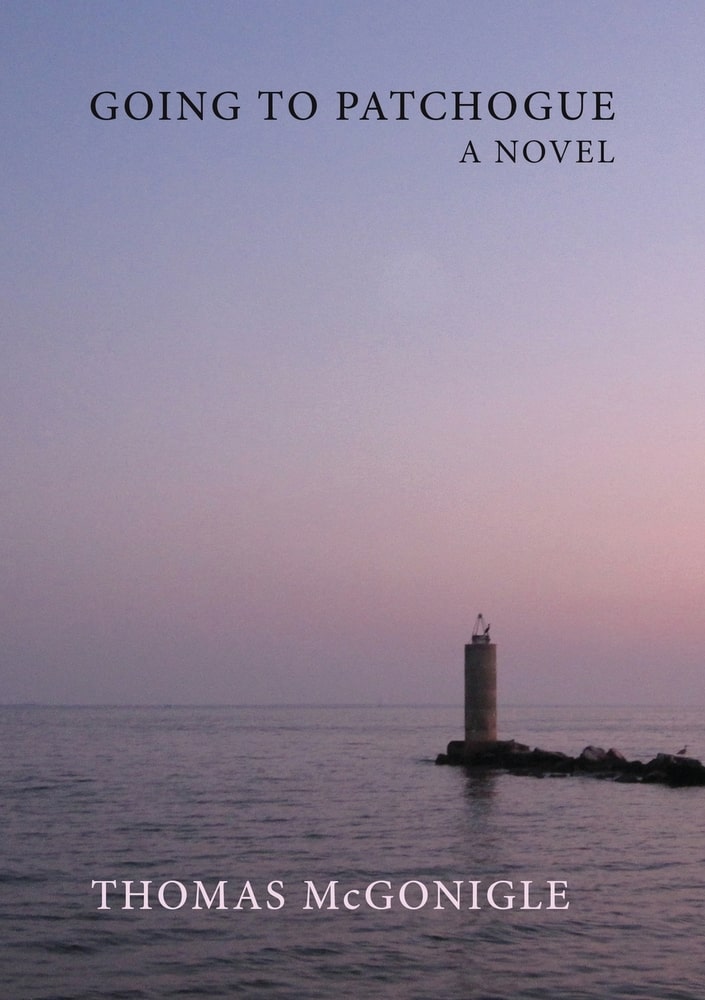

GS: Your novel, Going to Patchogue, has recently been reprinted by not Dalkey Archive but Tough Poets Press. Its opening flurry of paragraph-length “facts” about Patchogue and its people has been compared to the pages of epigraphs that kickstart Moby-Dick, although, at around 6,500 words, your extract total is about twice as long as Melville’s. You also echo the extract from the “Sub-Sub-Librarian.” What was your reason for inviting this comparison? And how much of these stories and pieces of information are based on research and experience versus imagination?

TM: Moby Dick by Melville is a great American novel, so linking Going to Patchogue with Melville seems both risky and obvious. Through the excess of this opening section, one hopes to make Patchogue familiar, a matter of fact, one could say, and therefore, no one really needs to ask what Patchogue is. Of course all of this is very much literary imagination but I cannot imagine any other way. The sure heaviness of such an opening I hope is lightened by way of the comic.

GS: Are you Ahab and Patchogue the white whale or vice versa?

TM: I am not Gregory Peck—or is that not how we all picture Ahab?

GS: There are many grotesque and horrifying instances among the opening factoids. What is it about the darker underbelly that draws your attention?

TM: Either I am thick or so indifferent to such distinctions that I do not recognize them as such. While I never felt the calling to the Catholic priesthood, I had been an altar boy long before the current obsession with such. I do remember reading or knowing about the duty of the priest in his listening to a confession and how he was trained to listen and to avoid responding as that was not his job—he listened to both venial and mortal sins and he was to listen without commentary: murder, robbery, being snide, or sneering at a person in authority…that listening caught me and then the grandeur of his saying, “And now say a good act of contrition.” I go on but a writer must record as carefully as possible and as indifferently as possible but of course I know the differences and that is revealed in my choice of words.

GS: You mentioned that you don’t like novels that have identifiable beginnings and ends, characters, and plots, etc. Where does this aversion stem from? Do you believe a kind of deconstruction is a truer reflection of ostensible reality? I think it’s worth quoting this passage from Going to Patchogue: “Here we are pages later and not a single character has made the scene; there has been no conflict laid into the story, there is no motor installed in the locomotive of plot, no sex to grease the wheels of the pages.”

TM: I don’t recognize any sort of aversion, or I am not sure what the word deconstruction might mean, as I am not an architect laying out a plan for a building. I am simply describing a going to, a being in, and coming back from a village on Long Island, sixty miles from New York City. I hope that my readers will enjoy the tour of the village of Patchogue, which exists in times present, past, and future. I hope that when readers come back to re-read GTP, they will find a new version of Patchogue. Then they will have the delicious pleasure of comparing their memory of their first visit to Patchogue with their current visit.

GS: You told me that you “got off the train [in Bulgaria] in 1967,” and there’s a long section on that country in Patchogue. What drew you to Bulgaria, and in what ways did the country speak to you on a spiritual level?

TM: Thank you for reminding me of the importance of Bulgaria in GTP. I well know that riding on the LIRR is generally not a pleasurable experience, but it is an experience that my father endured for thirty years, commuting back and forth between Manhattan and Patchogue, so while I wanted to report on the going to Patchogue on the LIRR, I decided to spare my readers the repetitive experience of a second time on the LIRR by offering a trip to Bulgaria in 1984, when the Bulgarian Communist Party would be celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Communist takeover of Bulgaria. In my so-called personal life, I got off the train in Bulgaria in what was my second journey to Turkey, where I intended to visit friends from the Peace Corps, who, unlike myself, had by then spent a year in Turkey. My life changed as I walked up what I later discovered was Hristo Botev Boulevard, as the night was coming on. I stopped at a kiosk and asked for tourist information. I can only resort to the spiritual, for the spiritual has to be embodied in the kiosk owner’s need to use the toilet, and, as a result, the daughter of the owner was working in the kiosk. After asking for tourist information, the daughter replied “I speak English a little…” Seven months later, this girl (the daughter of the kiosk owner) and I left Bulgaria as husband and wife.

GS: Tell me about when you were arrested in Bulgaria for writing on tablecloths. Were you attempting to compose a prandial novel?

TM: No prandial novel. Lilia, my Bulgarian girlfriend (soon-to-be wife), and I were forbidden to stay in a student hostel in Vitosha (outside of Sofia), as we were unmarried and I held an American passport. We made our way to a nearby restaurant where the drinks flowed freely and I began to “instruct” Lilia in the English language by quoting titles of popular songs and writing them on the tablecloth. These were song titles such as “All You Need is Love” and “Strangers in the Night.” As we were leaving the bar/restaurant, my passport was examined, as were Lilia’s identification papers. Early the next morning in the house of Lilia’s mother, located in Nedeshda, a suburb of Sofia (Nedeshda meaning “hope” in the Bulgarian language), the police arrived and I asked, “What is this about?” to which an English-speaking officer responded, “This is Bulgaria, you need to come with us.” Lilia and I were taken by car to police headquarters at the Lion’s Bridge in Sofia. After some hours of questioning, the tablecloth of the previous evening was produced and each of my scribblings was circulated. A photo was then taken of me sitting behind the tablecloth. In addition to song titles, I had written “No Capitalists, No Communists, Only Free People.” The interrogation lasted six hours and then suddenly we were allowed to leave. That evening, Lilia and I discussed what had happened and I decided to travel on to Istanbul. Friends from the Peace Corps I was intending to stay with had unfortunately been forced to leave. They were discovered to have been taking LSD at a summer camp for the children of Turkish army officers. I realized then that I needed to return to Sofia to be with Lilia. We discovered, by way of her uncle, that we could ask to be married but that it would take about three months for the paperwork to be processed. I went to Dublin but didn’t last long without Lilia and went back via train to Sofia. One day, “by accident,” I met the undercover police officer who had arrested us. We saw each other in a park in Sofia by the United States Embassy, and he warmly greeted me like a long-lost friend. For the next three months, Lilia and I would often meet “Ivan the Agent” who took us to dinner time and time again, to the best restaurants in Sofia, where we endlessly talked about the accident of our meeting. I know that this all sounds fantastic but it is the simple truth. In April of 1968, Ivan the Agent told us that if we went to the Marriage Office, permission for our marriage would be there and also Lilia was given a Bulgarian passport to leave the country. We took the train across Europe (Venice, Paris, London) to finally arrive in Dublin. We lived in Dublin until October of that year, missing the events of 1968—Paris and Prague. Ultimately, we moved from Dublin to Menasha, Wisconsin, where my parents were living. Through all these experiences, I had the gift of being given another country—I would continue to visit in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond. I was inspired to write The Corpse Dream of N. Petkov, which was translated into Bulgarian. I often think that we don’t pick countries; rather, countries pick us. And I am fortunate that I was given Bulgaria.

GS: One of your allegiances is to Dublin. Has spending time there allowed you to more deeply commune with the soul of James Joyce? I know that our common friend James McCourt visits Dublin annually. Have you two crossed paths and perhaps clinked glasses of Guinness?

TM: The work of James Joyce has long been part of my imaginative life. Before his work, there was Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel. James McCourt is a dear friend and we share in common a vision of writing, trying to find the right words, feelings, and places—both physical and imaginary. Jimmy has provided wonderful cover blurbs for my novels but our Irelands are quite different. My Ireland exists because of my paternal grandfather, who came via boat from Ireland to Brooklyn at the age of twelve to find work. As a result, I hold an Irish passport. My version of Ireland appears in St. Patrick’s Day: Another Day in Dublin. Jimmy’s version of Ireland appears in the central character of Mawrdew Czgowchwz.

Neither McCourt nor I drink alcohol. Jimmy and Vincent live 22 blocks from me in Manhattan. I have an Irish EU passport but no one tries to buy my vote. The wife also has an Estonian EU passport and she too is never solicited for her vote.

GS: How would you say you’ve changed or grown as a writer since Going to Patchogue came out in 1992?

TM: Since publishing GTP in 1992, there have been several more books published—The Bulgarian Psychiatrist, Party of Pictures, and Empty American Letters. My novel Diptych Before Dying has only appeared in Bulgaria. There is one great quote about Empty American Letters by Eric Larsen: “This extraordinary novel simply starts out, sets out, and keeps on going and going and going, not necessarily in a straight line, and not necessarily to someplace—though certainly to 1444 and the battle of Varna, grim, and grimly—and unforgettably—rendered, and a fitting place/time to find at the end of this book which seems to me as much a book of someone thinking (rarity in this age) and thinking about his thinking and also observing not only the things around him that he’s thinking about but also observing the thoughts he’s having about them. And every single bit of this long, simultaneously inward and outward journey rendered in the most fascinatingly deadpan (but impeccably hyper-alert) mode, hardly new in the universe of McGonigle/Joyce/Beckett, but perfected here to a stupendous and wonderful degree.”

As to how I have grown as an author, that is perhaps not for me to say, though there is a continuing elaboration of the early books. I find that all the books seem to create a world of their own, which is accessible at any port of entry—if we think of each novel as a port of entry.

GS: Patchogue has been described as “A travel book for those of us who never travel, who never want to travel.” The writer Paul Theroux believes that the best writers are those who travel, even if it’s just to gain an indirect yet deeper understanding of their homeland, their hometown, and the like. Do you agree with this?

TM: One can either agree or disagree with Paul Theroux’s observation. However, I think of all of these novels that were given to me as gifts, resulting from my travel to these places—Patchogue, Dublin, Sofia. I hope someday Istanbul will give me a story, as I am on the ancient one-stop subway tunnel.

GS: What novel do you think deserves more readers? Why?

TM: The book Larva: A Midsummer Night’s Babel by Julián Ríos. It’s something to be read over and over again or to be read about over and over again as it never can really be read…it is to be constantly gone back to much in the way the Bible or the Koran are to be read by a believer. Every time I go to Larva I find a different line, a different page, and often it’s the same page but read now differently. I often imagine this is what Russians once upon a time did when reading Gogol or Tolstoy, and are they not the best readers in the world?

GS: One of the epigraphs preceding the first section of Going to Patchogue is by Evan S. Connell: “Each journey is the consequence of unbearable longing.” What were your unbearable longings then, and what are they now?

TM: MELINDA. MELINDA. Of course this is why one worries about not making it into heaven on the first time around and those possible long years of Purgatory though we were told by the nuns in St. Franchise De Sales School that time in eternity does not correspond with so-called earthly time…but I can imagine a long waiting in the dentist’s office….

[The following is a passage from Patchogue: “He is sitting in the dark in the MG. Lights turned off after he turned into the street. Careful to coast down the street and park just out of the light cast from the porch lamps. He is hoping Melinda will walk across the picture window, well, behind the picture window, across the living room. He looks. He sits. He looks. He waits. She will never appear in the window. He will start the car, drive very slowly past the house, turn on the lights, and then at the end of the road make a U-turn, come back as if just passing through…he looks…she is not behind the window, never is she behind the window.”]

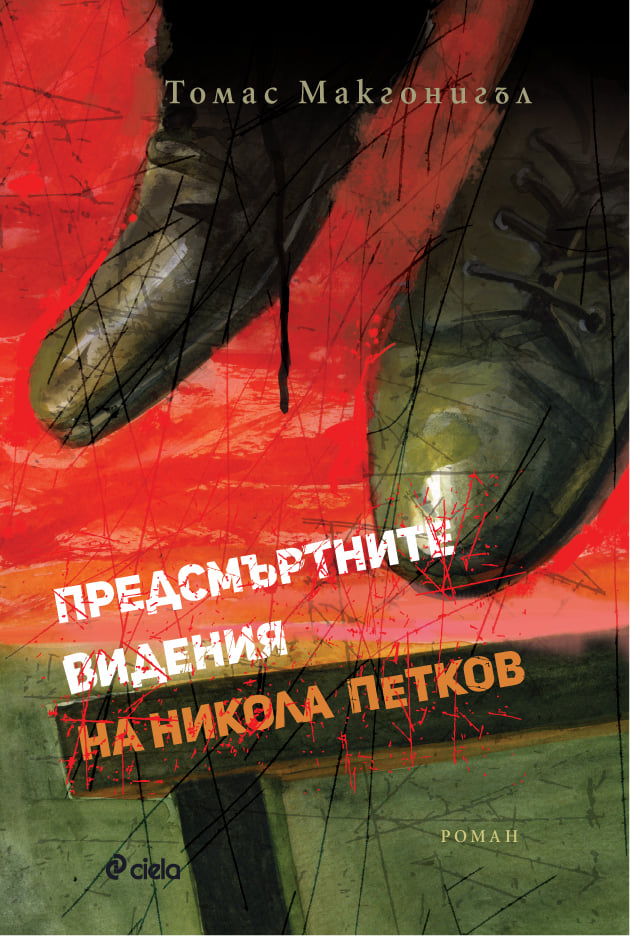

GS: Your debut novel, The Corpse Dream of N. Petkov, was published in 1987. You explained that it was influenced by James Joyce and Ignatius of Loyola’s spiritual exercises, particularly the idea of imagining your own death and the people looking on. You’ve done this on behalf of Nikola Petkov, but what do you see when you envision your own corpse dream?

TM: That is all so private and I did not have the calling beyond being an altar boy; though long ago, while talking with Julian Green, then the only American in the French Academy, he confessed that he was jealous of my Catholic boyhood as he converted too late so could never have the sense of being protected that I had as a Catholic boy who was an altar boy for eight o’clock masses at St. Francis de Sales in Patchogue.

No one can really imagine their own death but in answer to this question, again, one word: Melinda. As in the novel, which is really an excuse to drive by again and again Melinda’s house in East Patchogue…. I wonder what she will make of this incident which I hope is not tomorrow.

A detail from my life at the age of six: my sister (who is two years younger) and I walked to the beach in Patchogue, and when we came back home, she collapsed with what was later diagnosed as polio. The why has always been part of my life. She spent a year in the hospital, and to this day, though she has lived a complete and useful life as a school teacher and mother, I am always aware of this moment now so long ago, and it is formed into WHY? Of course, there is no answer, and all my books, every review, poem, story, etc., have been framed around that moment long ago in the house on Furman Lane. Each of us is a collection of questions and possible answers that never seem to stop the next question.

I have only been at one person’s deathbed: the mother of my wife Anna, but her mother was 101… I doubt I will make it to such a great age. I am grateful for my father’s death: in a parking lot: coming from or going to a bar in Saugerties—if only…but is that not one of the most beautiful possibilities… and there was no robbing of his body as a neighbor who was a local judge was driving by and saw the car and the incident…even the change in my father’s pocket was given to me…but I am consoled to a small degree by the availability of The Corpse Dream of N. Petkov in Bulgarian and hope to see it translated into French and German—probably too much to hope for it to appear in Russian and Turkish…but my other novels…Empty American Letters, The Bulgarian Psychiatrist, St. Patrick’s Day: Another Day in Dublin, Party of Pictures…and I must not forget WHAT I AM CURRENTLY DOING and the one coin to hand: The Glacial Carnival, which I also think of as the story of my three wives, one after another…wonderful comic moments in France, Bulgaria, New York City, and many other places to be revealed.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as exclusive letters from John O’Brien, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Thomas McGonigle is a writer, literary and art critic, university professor, and journalist. He has received several awards, including the Notre Dame Review Book Prize (2016). His novel The Corpse Dream of N. Petkov was first translated into Bulgarian by Ivanka Tomova for the Syvremennik magazine in 1991 and was republished by Ciela Publishing House in 2019. Inspired by the story of Nikola Petkov, a politician and member of the opposition, executed by the Communist regime, McGonigle introduces his readers into the setting of the National Court through the stream of consciousness of Nikola Petkov himself.

McGonigle is also author of the novels St. Patrick’s Day: Another Day in Dublin (2016), Going to Patchogue (1992), Party of Pictures (2023), and Empty American Letters (2023). He is a contributor to the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, Newsday, the Chicago Tribune, and The Guardian in London.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.