In her NYT May 2024 poetry column, Elisa Gabbert acknowledged that though critics and readers love to talk about a poem’s “speaker,” that’s not an easy term to pin down. She wonders whether our use of “the speaker” gives us an excuse to think less deeply about the degrees of persona or “spokenness” in any given poem. A couple of American poets for whom the term “speaker” seems less pressing are Mark Strand and W. S. Merwin. Their short poems focus on the moment and the passage and what is missing. In the first of three stanzas of “Keeping Things Whole“ (“In a field / I am the absence / of field.”), Strand refers to a “field” as “of field,” rather than “a” or “the” field. It is something general and he uses it as only one example of what his life is like. In the second stanza he writes that when he leaves, the air feels back behind him as if he had never been there in the first place. His absence does not fragment or upset the world. The third stanza expands beyond the speaker’s personal experience and uses the third-person pronoun “we.” Similarly, Merwin’s “speaker” in “A Contemporary“ finds himself “climbing out of myself / all my life.” They share an urgent and often impersonal tone in their poetry that enables them to access a timelessness and establish wide fields of experience in their work. Like them, French poet-translator Henri Meschonnic (1932-2009) writes in “the images that resemble me come from far away like a story“: “I am not in what / I seek but in what escapes me.” As poets, Meschonnic, Merwin, and Strand attempt to follow Montaigne’s practice: “I do not describe being. I describe the passage… from minute to minute,” On repentance, III, ii, 80).

Meschonnic, who might lay some claim to being the Montaigne of the twenty-first century, spoke of the infinite, exile, and our interdependence. In a world of polarization and divisiveness, readers may welcome connection. His untitled poems interrogate boundaries. Today, images of disruptions are imprinted on the world’s consciousness: a toddler washed up on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, a refugee passing his infant son through a barbed wire fence, migrants swimming across the Rio Grande, a young Ukrainian crossing the border and leaving her only home, who says, “I am walking to nowhere,” people at the Republican National Convention waving “Mass Deportation Now!” signs. “Worlds reach out” in the gaze of Meschonnic’s poems. The silence he captures at the Jewish cemetery in Radon, Poland, is the same silence we feel today at the mass burial sites in Ukraine, at Gaza’s Al-Shifa hospital, and south of the Mexican border. Though the human condition is exile, the Red Sea parts all life long. For Meschonnic, after each disruption, the poem brings us together.

As “worlds reach out” to him, what matters to Meschonnic is that the emotion passes from the subject who thinks, who knows, who wants, who has emotions to the subject of the poem. The poem happens only if it acts on the reader. Central to the poem’s experience is the concept of interruption. According to “when the names have left them,” interruption—similar to walking and breathing—implies resumption in Meschonnic’s Heraclitean flow of language.

when the names them

they became a river

and this river flows in us

I don’t know how to do anything else

but to be its movement

that carries us away

in the noise we shout to each other

our

names

Like Martha Graham inscribing her body through an empty, quiet room, Meschonnic’s uneven fragmented lines move through the mouth and ear in an unconstrained kinesthetic experience. Disrupting the line is a form of control and part of the greater action, allowing us to explore the unknown in ourselves.

The poem’s rhythm—in which the lines are enjambed and the thoughts fragmented—produces the corporeality of self-interruption. The interruption combines with the poem’s moment-by-moment engagement with the senses, inviting readers to participate in a flow that adjusts our world in an activity through which we become more empathetic. Because of the focus on sound, Meschonnic’s poems exhibit the continuity of the spoken rather than printed word. The best way to experience his poems is to read them aloud or hear them as a physical experience. He explains in an interview with Serge Martin published in Le français aujourd’hui, “It is physically in terms of syncopation that I hear the interruption of the end of the line, the poem being unity, unity which is itself only a passage, only a moment which is interrupted in the long poem that we never stop writing, and where we can only interrupt ourselves. And as Hugo once again said, life is ‘an unfinished sentence.’ We are in the unachievable. Moments, little fragments of infinity.” For Meschonnic, poetry is a transitive activity that does not create its own world but transforms our relationship with the one we live in. The disruption of the listener’s expectations and the arousal of a desire for the reestablishment of metric normality give the poem, like highly syncopated music, its forward momentum. Even the experienced reader cannot find a formal complexity in a moving target. Meschonnic does not intend his poems to be read individually but calls them a series of interruptions and explains that’s why, except at the very beginning, he doesn’t use capital letters or titles, because the poems are just interrupted fragments of an indefinite series of poems; the unity is the book of poems. Not to mention the overall unity, which is all the books written in the course of a lifetime.

Like metadiscourse in conversation or the ripples on a lake, interruption in a poem helps readers decenter their perception of the line long enough to assimilate with the writer’s world. “Entendre” is French for both hear and understand. Interruption helps the reader or listener focus. It helps the reader be present and open to the poem. It also encourages the reader to restate and contextualize ideas, to encode the poem into the reader’s own contexts and experiences. It directs the reader to identify and empathize, in short, to experience a mutual social presence. For Meschonnic, voice is relation. The physicality of rhythm transforms the reader via a kinesthetic experience. This is how the rhythm and subject of Meschonnic’s poems speak to our divisive historical moment. For him, the basis of change in a democratic society is an abandonment of self.

An early poem, “Those who speak have a country they have,” sets the tone for the social significance of his immense output. The interrupted syntax in the poem’s opening grabs our attention, assonance carries us through the middle, and rhyme provides closure.

Those who speak have a country they have

a voice joyous with language

they do not see their tracks

they become their tracks

they carry their borders in their mouths

though their story dances on thorns

they are a book that needs no other books

their laughter rebuilds a culture

all tears lead there.

Refugees are indeed wandering everywhere, but they are not lone planets without a sun because they can tap into the power of language with all its living parables and myths. As Meschonnic asserts in his rhythm manifesto: a poem is made from what we go towards, what we don’t know. For him, as for Bob Dylan, “nostalgia is death.” So, language, not political lines on a map, connects people and gives them strength. For him, bringing language into play brings society itself into play. His poems are deliberately “walking to nowhere,” to use the young Ukrainian refugee’s words. The tracks appear after the steps are taken. Refugees carry little with them aside from their language, the stories that have been passed down through generations. As readers, by engaging in the poem’s rhythm, we help “rebuild a culture.”

To create the largest possible community of readers, Meschonnic uses a simple lexicon. Liberating words from associations, he refuses to describe. He uses the indefinite article so that “a book” is like any book, where readers can recognize a universal situation. He uses no proper nouns. Personal pronouns define relationships, with the second person singular often acting as agent, resulting in a pluralization. His more common pronouns are “you” and “we” rather than “I.” “I am not always me“ thus becomes an exchange with the other: “I’m not always me / sometimes I am a tree a / sound in the air a breath a flight / footsteps / a glow in you / a calm / that you breathe.” In Poeticized Language: The Foundations of Contemporary French Poetry, Jean-Jacques Thomas indicates that Meschonnic’s words are simply not present in Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Verlaine, or Mallarmé. This lack of literary iconicity may explain why Meschonnic’s work is often dismissed as too “different” or too “difficult.” The reader does not recognize the text, to use Michael Riffaterre’s term, as a “latticework of other texts.” Instead, as Michael Bishop notes in a book review, “Meschonnic remains sensitive to the ever-changing structure of the self, the fact that our life’s narrative is continually beginning over again, demanding a constant improvisation of our rhythmic accord with the space and the events around us.” In “we lacked words,” the words return to meet the moment that seems to leave us speechless.

we lacked words

we became like a book

with nothing but margins

the words returned

like a memory

safe from oblivion

listening to what’s coming

to remake our language

with no words

at the bottom of time at the brink of

speech

Historically, Meschonnic shares René Char’s (1907-1988) concision and presence and recalls Paul Eluard (1895-1952)) and the surrealists. However, the power of Meschonnic’s voice is not ordered in images so much as it is contained in rhythm. He found a voice that undoes the lyricism-epic dualism, writing. As he mentions in our interview in Diacritics, “I think my poems take place in this changing moment of French poetry. Poetry is not behind them. I am working in the most common language. I am trying to utter a language that works out its own poetry.” For him, poetry modifies our being in the world through the modification of language. To think language without using conventional concepts, he wrote without using conventional forms. If the poem is the adventure of the subject, he writes in The Literary Review, it will always be novel, making the concept of avant-garde meaningless.

As translators, we try to embrace strangeness and a sense of alterity—what we have difficulty hearing and what we do not know how to assimilate. Translating involves listening to what resists transposition into the patterns that tradition offers. Accessing Meschonnic’s unique style of using simple language, little punctuation, spareness, and lack of titles to approach deeply existential thought challenges our word choice and syntax. To convey the oral quality of Meschonnic’s poems, we use only the most everyday verbs and nouns (his poems are nearly adjective-free) and look at individual words (no matter their simplicity). A second challenge of translating is the tendency in French to universalize, which often leads to the most general reference, while in English poetry, universals are often reached through an outer surface of sense-data. We lean towards slightly more concrete particulars. Finally, we try to honor the rhythm of the French, placing the stress on the last syllable of each line, as is mostly the case throughout the poems. We listen for the subject in the enjambment, in the accentual organization, in the words Meschonnic rhymes and the links he forges between different words. The interplay between silence and sound is apparent in the white space of “our life a.” The following poem is an example of how we attempted to translate aspects of Meschonnic’s style into English.

our life a

story that only begins each time at

the next sentence

we cannot follow only

breathe but

when we do speak

the body rejuvenates

we drink to you to me the table

holds and the life between us

creates space that matches our rhythm

we can start again we

listen to one of many stories

we already know

the voice

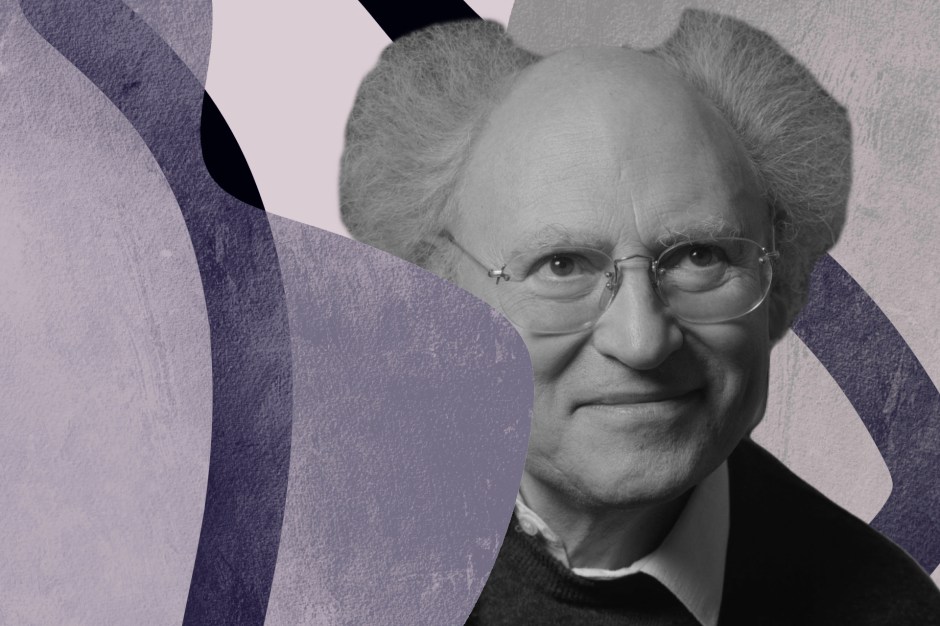

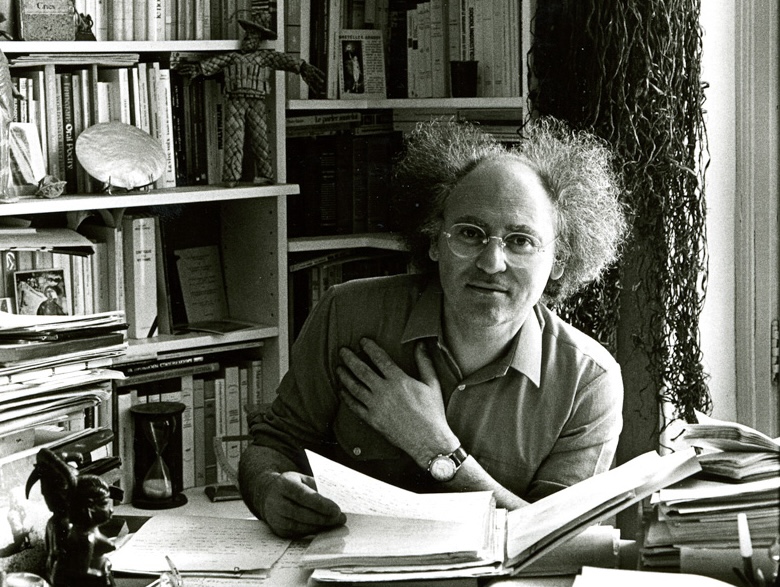

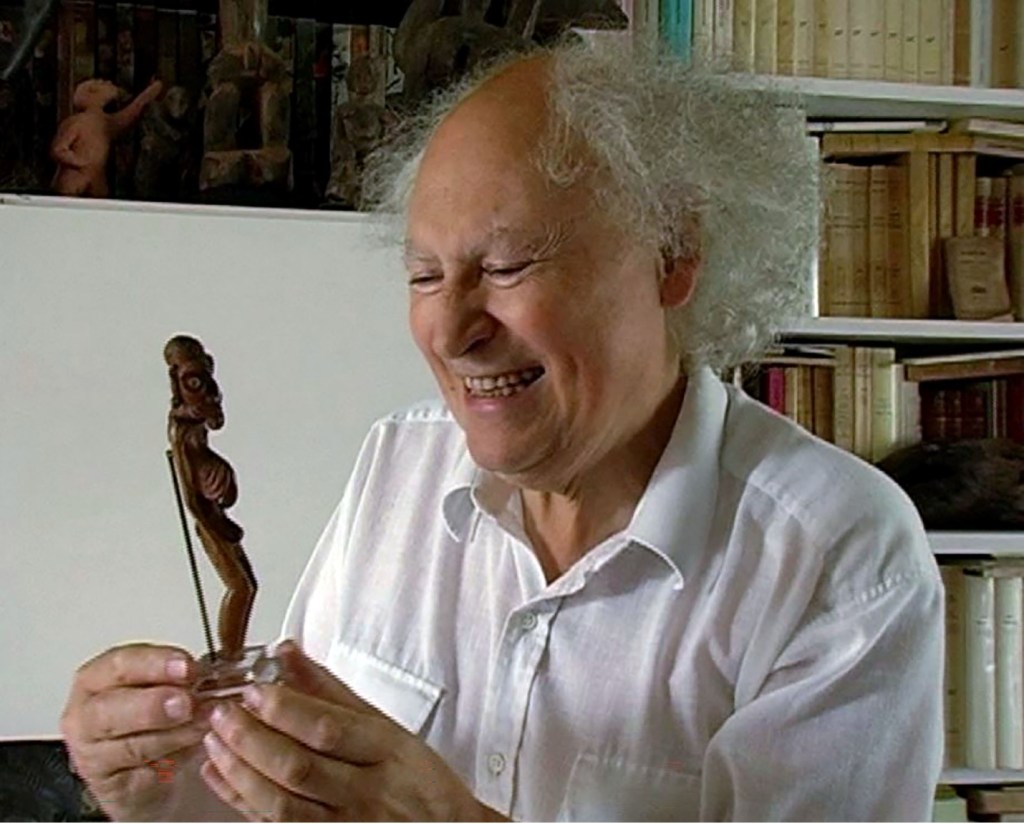

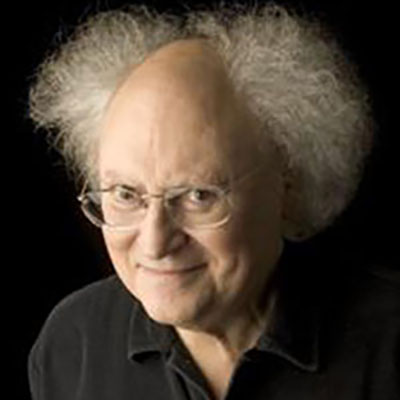

Who is this poet-translator whose poems are unlike any others being written in English? Meschonnic lectured and gave poetry readings in cities from Beijing to Barcelona; he was a visiting professor at Columbia University, Louisiana State University, the University of Virginia, and The School of Criticism and Theory. His poems exist in many languages, including Hebrew, Serbian, German, Japanese, Arabic, Macedonian, Italian, Spanish, Croatian, Portuguese, Polish, Korean, Persian, Bulgarian, Bengali, Dutch, and Romanian. Surprisingly, his poems have never appeared in English in book form. A third of his nearly sixty books are collections of poetry. Meschonnic received many prestigious awards, including the Max Jacob International Poetry Prize, the Mallarmé Prize, the Jean Arp Francophone Literature Prize, and the Guillevic-Ville de Saint-Malo Grand Prize for Poetry. His poetry—the most important aspect of his work—has been celebrated worldwide but neglected, infamously, in American translation.

Meschonnic’s family history was defined by exile. According to his cousins, Claude and Jacques Treiner, Meschonnic’s father and mother were born in Kishinev, the capital of today’s Moldova, in 1902 and 1903, respectively. They survived the 1903 Kishinev pogrom. In 1926 Meschonnic’s parents emigrated to France. As Romanians in France, they had to flee from the roundups of Jews by living in the southern zone until the liberation. At the time, he was only ten. In 1948 the Meschonjnic family obtained French nationality and changed their name. His wartime experience informed many of his poems.

I have nothing left but my journey

I come after the last one

came with those who do not have

more than their life in

their voice

For Meschonnic, as for Anne Frank, the life left in his voice is the experience of writing.

After the French liberation in 1944, Meschonnic studied classical literature, completing his baccalauréat and advanced study at the Sorbonne, married Marietta and, in 1960, served as a soldier for eight months in the Algerian war. His sons were born in 1958, 1960, and 1962. At thirty, he published his first poems in the magazine Europe in 1962. In his late thirties he accepted a teaching job at the Experimental University Center of Vincennes (later renamed the University of Paris VIII), where he worked with François Châtelet, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, Michel Foucault, Alain Badiou, Jacques Lacan, and others to create the new university. At forty, he published his first book of poems. He divorced and married Régine Blaig in 1976. In the firmament of literary giants, he is best known worldwide for his translations from the Old Testament and the 710-page Critique of Rhythm: Historical Anthropology of Language, published in 1982 at the age of fifty. He died in 2009 at seventy-seven. His last book of poems was written mostly in the hospital at the end of a ten-year struggle with leukemia.

And here, appropriately enough, is a brief clip of Meschonnic in his own voice:

Henri Meschonnic (1932–2009) is a key figure of French “new poetics,” best known worldwide for his translations from the Old Testament and the 710-page Critique du rythme. His poems appear in more than twenty languages and have received many prizes, including the Max Jacob International Poetry Prize, the Mallarmé Prize, and the Guillevic-Ville de Saint-Malo Grand Prize for Poetry.

Don Boes is the author of Good Luck With That, Railroad Crossing, and The Eighth Continent, selected by A. R. Ammons for the Samuel French Morse Poetry Prize. His poems have appeared in The Louisville Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, CutBank, Zone 3, Southern Indiana Review, and The Cincinnati Review.

Gabriella Bedetti’s translations of Meschonnic’s essays and other writings have appeared in New Literary History, Critical Inquiry, and Diacritics. She and Don Boes are seeking a publisher for The Butterfly Tree: Selected Poems of Henri Meschonnic. Their translations appear in Puerto del Sol, World Literature Today, and are forthcoming in The Southern Review.