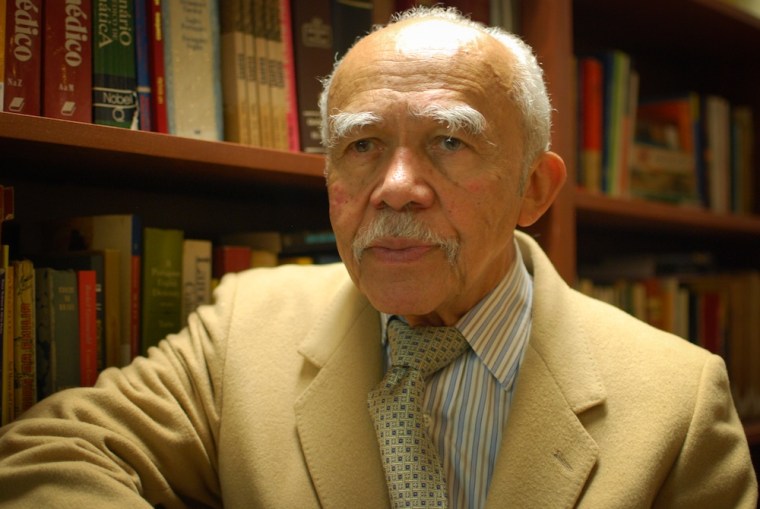

About Domício Coutinho: Born in João Pessoa, Brazil in 1931, Domício Coutinho emigrated to the United States in 1959, eventually earning a Master’s and Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the City University of New York (CUNY) in addition to his bachelor’s degree in Aristotelian Thomistic theology from the Gregorian University of Rome. In 1986, Coutinho, with his wife and two sons, began a business in real estate appropriation and management of properties. In 1999, Coutinho founded The Brazilian Writers Association of New York (UBENY). In 2002, he was admitted as Commander into the Order of Rio Branco, a Brazilian Institution honoring those who have distinguished themselves in cultural and patriotic achievements. In 2004, Coutinho founded the Brazilian Endowment for the Arts (BEA), a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving and promoting the Brazilian Arts, Literature, and Cultural Traditions for the Brazilian/American and Latin American Communities. That same year, he created The Machado de Assis Medal of Merit to honor those who distinguish themselves in Brazilian Cultural Traditions. In 2006, Coutinho founded The Brazilian Library of New York, which houses 7,000 titles, with an auditorium for events, conferences, literary gatherings, films, and dramatic performances. The library has been visited by prominent representatives from government, diplomacy, and academia.

Aside from an untranslated poetry collection titled Salomônica and a recently translated novel titled Incredible Revelations of an Earthworm, Coutinho published a novel in 1998 titled Duke, the Dog Priest, which was translated from the Portuguese by Clifford E. Landers and brought out by Green Integer in 2009.

I interviewed Domício Coutinho here and here.

“The love that takes us to heaven is the twin of the hatred that casts us into the abyss. In the hands of the two, we never know where we are, and care little about the end.”

The worm. A creature unsung at best and unseemly at worst. When remembered at all, it’s often used as an insult or invoked as the eater of the dead, memento mori, excepting the term “bookworm,” although even that can have a negative connotation, of being at the margins, away from the thick of life. The worm, almost as unjustly reviled as the snake. Yet the worm was a muse of Charles Darwin, a creature that boasts no bones, making it more flexible and sinuous than humans could ever hope to be. Like vultures, they are decomposers, taking on the thankless task of cleaning up the world. Notions of the morbid aside, an abundance of these hermaphrodites is a sign of healthy soil. Still, none of these are reasons why I invariably lean over during walks and pick up with naked fingers the worms marooned on asphalt or concrete, those on the verge of baking alongside their desiccated kin. It’s because life deserves to live. This respect for the beings in the web of nature, of which we’re but a thread, is something Domício Coutinho possesses in Aesopian spades. It’s a respect that can be traced to a wider reverence for creation, including the creation of creation, that first story which has within itself every story, including its own endless permutations: “Those stories and visions convinced me of one thing, that the human mind comes from long-lost eras of history, fragmented, however, like a mirror shattered into a thousand pieces, reflecting the world around it, ever since the first word was uttered.” Throughout Incredible Revelations of an Earthworm, Coutinho gives us his tinkered and tailored versions of these oldest of tales. According to this novel, worms are creatures of the highest order, including a vermicular character in particular: “She was a noble, her blue blood came from the origins of the world. The first animal to appear on the planet. The chrysalis in which the plants transformed. She descended directly from the first woman, to whom the Great Kyrios said: ‘Let there be the earthworm!’”

All these tales exist within one or more frame tales, the first one featuring an observant and thoughtful if at times judgmental man who spends most of his time along the beach, which, we are told, is a place ripe for creative minds: “Beethoven is said to have conceived the Sixth Symphony beside the ocean. Shakespeare wrote The Tempest listening to the waves.” The beach, a perfect foundation for a novel obsessed with inception, especially considering how water is the stuff of life, or at least of life as we know it, the beach as the bridge between one creation story and that of another, our momentous transition from water into land, when we turned the sea inside out and kept it within ourselves, our bodies, more than half of which is made up of water. We are ocean sacks. About his own creation, the protagonist says, “I knew that the Potter, when He made me, was dead tired, as he left me all twisted and out of place. And his breath was short. Instead of entering through the nostrils, it escaped through the forehead.”

As a character, Eve eventually boils down the myth of creation into its dichotomous essence: dark and light. Darkness, being photophobic, engages in a well-nigh nuclear war with its radiant counterpart. This section of primordial fireworks is but the stage for further tales and tidbits. Before and after, we learn why the flamingo stands on one leg all day long, that the movement of the crab delineated Einstein’s theory of relativity, why the fishes of the earth lose control at the sight of a worm (hint: it’s for reasons lascivious), how Man came from Woman rather than the reverse, and how Neptune invented nepotism. We also learn about vermiphagos kings, the donkey Zeferino who participates in the events at Golgotha, Washington’s pact with the Devil, a shark with well-founded misanthropy, the meaning of “skull fights,” and more.

Having studied Aristotelian Thomistic theology at the Gregorian University of Rome and later quitting the seminary, it should be expected that Coutinho offers readers religious criticism that focuses mostly on Christianity (although this is a novel that incorporates paganism into its cosmos), both through the protagonist’s mouth and the worm’s, those incredible revelations as promised by the title: “During all the drama of the Passion, he had not appeared even once, nor said a word during the judgment and the death on the hill between two criminals. Nothing to comfort, nothing to reprehend, nothing. Just as if he didn’t want to know about Him. That silence must have been his greatest torment. What father would close his eyes and leave his son alone in the hands of executioners, dying on a cross?” What father, indeed. Another example, this regarding faith, referred to with a feminine pronoun: “She speaks and inspires really anyone, but suddenly abandons her most devout followers and clients, those enraptured ones who bought her enchantments at inflationary prices. Those she treats like a femme fatale who takes pleasure in painting the splendors of the few instants she spends with lovers on earth, deluding them with the promise of sempiternal ecstasy in a golden palace, without to the present day ever having given the tiniest demonstration that such a palace exists.” This type of criticism is similar in spirit to Coutinho’s first novel, Duke, the Dog Priest, which professes against the injunction of celibacy, although that book (my personal favorite) is more Márquezian, with a nested structure more traditionally based in character and an over-arching narrative, while Incredible Revelations of an Earthworm’s structure and style is more Voltairean, an expository-heavy novel of ideas and lambastes fueled by fanciful zoology. Still, these books also share a necessary humorous irreverence. Let’s not forget that the truest reverence comes with more than a hint of irreverence because to love something you must know it for all it is—the difference between blind faith and something insightful, something truer.

By the novel’s end, Coutinho distills stories into two overlapping dichotomies: the stories of Homer and the stories of Moses, the former stories ruled by Gods and the latter by God: “One day Homer said, ‘Look, Moses, there are already enough myths for a forest of books.’ Moses, less dour that day, agreed: ‘You’re right, Homer, let’s bring everything together and make it just one story. I’ll tell it one way, you another, and in the end, we’ll choose which is prettier.’” Which is the ugly story and which the pretty, which the dark and which the light? Just ask the crab that walks backward but is really walking forward and he’ll tell you that it’s all a matter of perspective.

Coda: After I first read Coutinho’s wonderful debut novel, Duke, the Dog Priest, and wrote about it for my column Invisible Books, I tracked him down for an interview, facilitated by his kind son, the historian Charles Coutinho. In that rare interview, Coutinho Senior says, “I long for the day that [Incredible Revelations of an Earthworm] will be translated into English.” My review-interview project spurred the interest of Clifford E. Landers, the original translator of Coutinho’s first novel, who took on the task and helped make a nonagenarian’s dream come true. Afterward, in my capacity as volunteer acquisitions specialist, I sent the manuscript to Richard Schober for potential publication at Tough Poets Press. And the rest is a product of yet another creation story.

This piece was originally published as the introduction to Incredible Revelations of an Earthworm by Domício Coutinho (Tough Poets Press, 2024).

Editor’s note: The aim of Invisible Books is to shine a light on wrongly neglected and forgotten books and their authors. To help bring more attention to these works of art, please share this article on social media. For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.