George Salis: How did you come across Alexander Theroux’s work and what was your impression of it?

Gary Lloyd Noland: I remember chancing upon a copy of Three Wogs in a bookstore over twenty-five years ago. I was impressed with the mastery, density, and erudition of Alexander Theroux’s prose style, not to mention its subtle satirical edge. Shortly thereafter (within a year or two), I encountered a remaindered copy of Darconville’s Cat at a bargain bookstore off of Interstate-5 in Northern California. That it was remaindered has bothered me to this very day.

Reading Darconville’s Cat was a seminal, life-changing experience for me. It was like discovering, as a composer, a harmonic language I’d never even known existed. I would liken the experience of my first reading of Darconville’s Cat to my discovery, in my early twenties, of the music of Richard Strauss—a composer whose harmonic language has a four-dimensional quality to it that beggars description and defies analysis. The achievements of Richard Strauss, who died in 1949, remain unsurpassed by any composer I know of since then. I view Alexander Theroux, if you will, as the “Richard Strauss of writers.”

Simplicity, as I view it (in the case of Richard Strauss, an unparalleled gift for melody), is an essential ingredient of complexity, as one can assume that the latter, by definition, embodies the former. Modernism frequently makes the error of likening complexity to “complicatedness,” which all too frequently excludes simplicity and becomes a license for randomness. This is the point when foundational structures begin to crack and even fall apart. Not a single composer I know of has managed to take up the torch where Strauss left off in terms of being able to handle compelling formal structures on a massive scale, as he did. My perception of Strauss’s music is, perhaps, not dissimilar to that of pianist Glenn Gould’s, who likewise held the unconventional conviction that Strauss (who is often considered by the academic mainstream to be déclassé, as opposed to, say, Mahler, Berg, and Stravinsky, who are considered de rigueur) to be by far and away the greatest composer of the 20th century. I would even one-up that by saying that he is the greatest composer since J.S. Bach. Both Strauss and Bach, not generally viewed as “innovators” per se, may be thought of as the supreme culminators of their eras, having picked up where their predecessors left off. If history repeats itself cyclically, then it would stand to reason that the next supreme musical “culminator” will be a composer who dies somewhere in the neighborhood of the mid-22nd century.

Any single page out of Darconville’s Cat has a revelatory glow to it that makes the vast preponderance of other writers I know of (even some of the very best) pale by comparison. The “simplicity” of Alexander’s writing is found in its fundamental coherence, which may, in part, be due to what appears to me his renunciation of a certain kind of free-associating stream-of-consciousness, or “atonality,” that can easily cause a reader to lose the thread of the narrative (I have to confess this weakness I have with regard to writers such as Pynchon and D.F. Wallace). There are many exotic dissonances that, I think, can be functionally explained within the larger tonal structure of Alexander’s writing. (I am a composer, not a literary critic, so I am attempting to describe his writing in purely musical terms). I have not, in the past 26 years, been able to replicate a reading experience on a par with Darconville’s Cat (and that would not disclude Ulysses), just as I have never been able to replicate the listening experience of certain Strauss operas or tone poems, or even some of his youthful chamber works (such as the Piano Quartet, Op. 13 or the Violin Sonata, Op. 18). On a smaller scale, I can envision an analog between Alexander Theroux’s Fables and Richard Strauss’s rarely heard song cycle Krämerspiegel, both of which are unique and rarefied musical and literary gems, insofar as giving both readers and listeners alike the sense of traversing unexplored frontiers of literary and musical expression. I know of no other song cycle with the harmonic subtlety of Krämerspiegel nor fables with the esoteric “otherness” of Alexander Theroux’s.

Reading Darconville compelled me to rethink a writing project of my own that I had been immersed in for quite a number of years (an as-yet-unfinished magnum opus titled Venge Art), a project of some 300,000 words that includes musical scores and elaborate improvisation cues within the text for musicians, dancers, actors, and other participants, which is the precursor to my published “chamber novel” Jagdlied. The former may never see the light of day, as it is difficult for me to imagine finding the long swaths of uninterrupted time to make all the revisions needed in the text to ensure my satisfaction with it. It could easily take me another ten years to complete such a work.

GS: How did you go about “translating” Alexander Theroux’s poems into music? Poetry is one of the more musical forms of writing, so I assume each poem lent itself to a certain tempo, etc.

GLN: First of all, I should mention that, after setting a couple of translations (in English by John Willett) of Bertolt Brecht’s “Hollywood Elegies” (originally set by Hans Eisler in German in 1943) and experiencing first-hand the various hoops a composer has to run through when setting texts that are not yet in the public domain, my inclination from that point onward was to set only older (usually pre-twentieth-century) texts (i.e., by Robert Herrick, Ben Jonson, Jonathan Swift, Heinrich Heine, Eduard Möricke, etc.) where copyright would not be a concern so that I wouldn’t have to be bothered with all the bureaucrappic rigamarole that’s mandated to ensure one crosses all one’s t’s and dots all one’s i’s in the process of obtaining the various permissions needed to publish and perform them, etc. There is little or no remuneration for any of this and life is short….

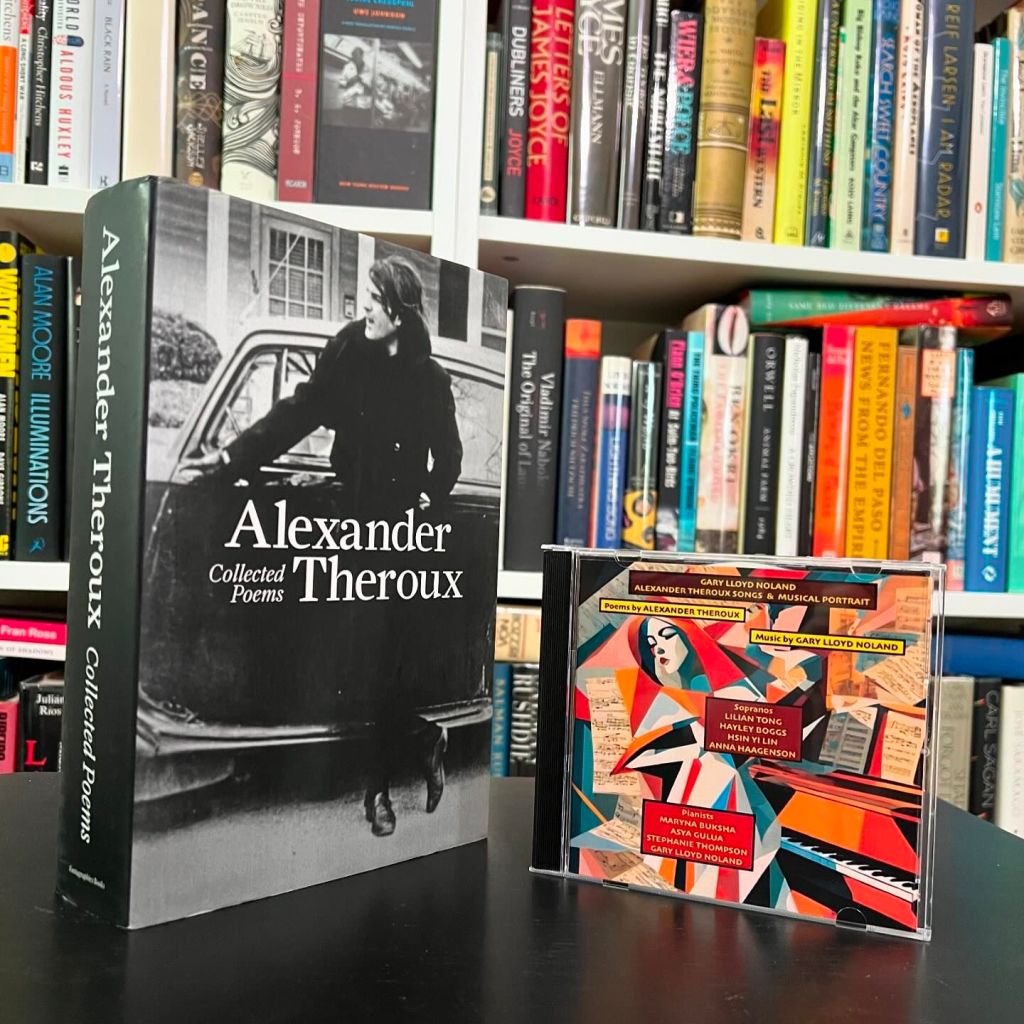

On the other hand, upon perusing Alexander Theroux’s Collected Poems (published by Fantagraphics) and receiving his permission to set his poems to music, I thought, because of my deep respect and admiration for his unsurpassed accomplishments as a writer, to make an exception in his case. Setting his poems in the past few years has been a singularly rewarding experience for me as a composer. I hope to plunge into more vocal settings of his poems in the near future. As it turned out, I had already contacted Alexander many years prior to embarking upon this journey after having been commissioned by flautist Tessa Brinckman in 2001 to compose a trio for flute, viola, and cello that was a loosely programmatic work based on Darconville’s Cat, which I titled “After Darconville” (Op. 52). Although the trio has been performed a number of times, I hope to have it recorded professionally at some point down the road.

To answer your question, when setting Alexander’s poems to music, I am influenced, quite naturally, by the overall mood, spirit, and ambience of the poems and tend to concern myself with the various musical considerations that arise for the singer(s) and pianist, in which the tempo, though not metronomically prescribed, does indeed come into play. Musical structure has always been important to me, as I tend to think of it in functionally harmonic terms. I have, over many years, developed the ability to modulate (i.e., smoothly segue) my way out of a paper bag from any key, howsoever remote or exotic, or any sonority, howsoever strident or contextually inexplicable in a tonal framework it might be, to any other key or sonority, always with an ear to its functionality within a larger context. It makes for an interesting parlor game for the very few who have such chops (pianists Robert Levin, Gabriela Montero, and composer Noam Elkies come to mind as musicians who can surely do this sort of thing. Oh, and speaking of musical parlor games, I’m reminded of the time that then resident composer David Del Tredici demonstrated for composer fellows at the Bloch Festival in Newport, Oregon, in 2002, his incredible skill at guessing a piece from hearing only a single note played on the piano, but I digress….)

There is always a bit of a chicken/egg quonundrum in terms of sensing what comes first. Is it more efficacious to harmonize the melody or melodize the harmony? I think such a process is in a continual state of flux. Sometimes, for purely musical reasons, I feel compelled to repeat words, lines, and complete stanzas, which, of course, distorts and/or elongates the texts from their originals (a by no means uncommon practice among composers). On the other hand, if I remained a purist (a quibbling pedant) and stayed one hundred percent faithful to the text from the get-go, word for word, a good deal of untapped musical resources would be lost in the shuffle.

GS: Why did you choose sopranos, in particular, to sing Alex’s poems?

GLN: First and foremost, I love the sound of the soprano voice. I am, however, increasingly inclined to compose works for more than just one voice with piano. Late last year Alexander asked me to set his as-yet-unpublished poem “Hymn of Vision,” which I ended up setting for soprano, alto, and piano, which can be heard (performed by lyric soprano Lilian Tong and pianist Maryna Buksha) here.

The only setting I have composed of Alexander’s poems that has not yet been performed or recorded at the time of this writing is an unpublished poem of his titled “It” that he sent me upon my request shortly after the initial worldwide onslaught of COVID-19. The poem was dated 14 April, 2020, which, serendipitously, happened to be my birthday. I went on to set it for soprano, alto, tenor, bass, oboe, French horn, double bass, and timpani and hope to have the opportunity of hearing it performed and recorded prior to my leave-taking.

I have always had a special fondness and affinity for vocal duets, trios, and quartets sung against piano accompaniments. There is a relative dearth of musical literature in that domain. The best examples, of course, are works by Brahms, in particular both books of his Liebeslieder Walzer, and various works from Rossini’s Péchés de viellesse (“Sins of Old Age”), a good many of which are pure musical gems. There’s a lovely set of five relatively unknown duets by Max Reger (Op. 14) for soprano, alto, and piano (heavily influenced by Brahms), as well as two or three works by Chabrier I know of. Of course, Schumann, Schubert, and Mendelssohn should not go unmentioned here. I am excluding discussion of operas, oratorios, Bach cantatas, and other vocal works with orchestral accompaniments, many of which contain a good variety of vocal combinations, but I am primarily concerned with songs and Lieder with piano accompaniments. Some of my unaccompanied duet settings of Alexander’s poems (Op. 147, Nos. 1-8) for soprano and alto were inspired by the two-part canzonets of Thomas Morley and various vocal duets by Henry Purcell, though stylistically and aesthetically they are more topically “up-to-date” in mood and style. Performances and/or recordings of such works are often quite difficult to come by. My suspicion here is that it may be a bit of a task to get solo singing prima donnas to cooperate with one another in such scenarios, which could very well account for the relative paucity of musical literature in these more intimate, less ego-flattering milieus. I view the modest addressing of this musical gap as one of many possible callings for myself as a composer.

GS: Your CD also features a musical “portrait” of Alex. How do you go about doing these types of portraits? In what way do you use instruments as brushstrokes, as it were?

GLN: Having attended a recital of musical portraits by Virgil Thomson in Boston back in the 1980s (with the composer present, whom I briefly met), I had decided, many years later, to embark upon a similar pilgrimage. Thus far, I have completed eleven such portraits (Op. 117), which, aside from the one of Alexander Theroux, include portraits of cartoonist/artist Robert Crumb, social critic/feminist Camille Paglia, American playwright David Hirson, English writer Will Self, French novelist Michel Houellebecq, French/Italian mezzo-soprano Lea Desandre, conductor/composer Michael Rosenzweig, English cultural critic Theodore Dalrymple, German operatic tenor & composer Daniel Behle, and Jazz pianist Darrell Grant (the latter of whom I have neither met nor know much about but whose musical portrait I was asked to “sketch” by the then head of the music department at Portland State University as a birthday gift for him, which was, for me, more akin to being hired to sketch a portrait of a stranger in an amusement park).

In the case of my portrait of Alexander Theroux, it is a multi-track “comprovisation”—a term I coined over twenty years ago but which has since gained some traction due to the leapfrogging advances in music technology. My decisions regarding instrumentation for the other portraits are largely intuitive and usually very much done on the spur of the moment. I have hundreds of such “comprovisations” in my catalog, which date back (in less technologically advanced forms) to the time I worked at the Harvard Electronic Music studio in the early 1980s, when Ivan Tcherepnin (son of Russian composer Alexandre Tcherepnin) was at the helm.

GS: At least to my untrained ears, your music tends to have odd time signatures and other compositional quirks akin to controlled chaos. Can you talk about your approach to structuring music and the overall aesthetic that informs it?

GLN: My comprovisations may be accurately described as a kind of controlled chaos, insofar as my reliance on the spontaneity of improvisation and, indeed, elements of randomness (especially in the distinctive employment of exotic timbres and dissonances) go, versus the methodical rigor of a notated composition. When I commit pieces to paper, however, it is an altogether different process. Every single note and gesture (as in my settings of Alexander’s poems) involves a painstakingly slow and methodical decision-making process in which each and every detail is meticulously (almost akin to an attempt at committing the “perfect crime”) calculated and sculpted with an eye to the structural integrity of the work. (Incidentally, I frequently find myself judging other composers by how well they can write fugues; if they’re not up to the task, as tends to be implicit in their music, whether or not they actually spend any time composing fugues, I tend to lose interest PDQ.) I do on occasion employ harmonic progressions that I can “generate” on paper using methods I have developed over the years, using my own original “Grand Unification Theory of Harmony,” an all-encompassing system that I teach to some of my students—both daunting in its complexity and (I would like to think) elegant in its simplicity—which I have developed over the past forty-plus years. My settings of Alexander’s poems “All Roys are Fat” and “Prayer of a Fat Man” are good examples of my employment of some of the more systematic elements of this technique. When I make use of the techniques derived from my own harmonic system, they tend to lend themselves advantageously to compelling musical structures, especially where the transitions (i.e., modulations) from one moment to the next are concerned.

As far as the aesthetic that informs my music, I am influenced by the entire Western classical music canon dating from the early Renaissance to the present. I view myself fundamentally as a romantic composer, but while hearkening back to tradition, I am unable to ignore the present, even if I find it at times antithetical to my own musical sensibilities; this is where hard satire can come into play via the juxtaposition of stylistic references. In this sense, I have to acknowledge George Rochberg (who once invited me to his home in Philly way back in December 1983) as an important influence on my development as a composer. I view the premiere of his Third String Quartet by the Concord Quartet in 1972 as one of the seminal musical moments of the latter half of the twentieth century, perhaps on a par with the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring some sixty years prior thereto (1913).

As for “odd time signatures,” I think, by 21st-century standards, I would be considered by many seasoned listeners to have an inborn tendency to gravitate towards being rhythmically on the more “conservative” side insofar as I tend not to venture out on a limb to engage in polymetrics and/or excruciatingly difficult-to-count polyrhythms unless, of course, the music screams for it. One can listen, perhaps, to the music of Brian Ferneyhough, Helmut Lachenmann, Györgi Ligeti, Eliot Carter, Beat Furrer, and many other 20th– and 21st-century composers influenced by the Darmstadt School for what might be considered truly “odd time signatures.”

GS: You wrote a maximalist work titled Jagdlied: a Chamber Novel. Can you talk about the aesthetic of this work and what you mean by “Chamber” novel? What inspired you to transition from composing music to composing prose?

GLN: I call Jagdlied a “chamber novel” because I envision it being performed by a narrator and (taking under account severe budgetary restrictions in a culture such as ours that is unwilling to invest in larger-than-life visionary works) a relatively tight and small chamber ensemble. I like to think of it as a poor man’s “opera” of sorts. It is flexible in its design (as expounded in detail in its lengthy appendix, which consists of elaborate performance guidelines not unakin to a Baroque table of ornaments, albeit on steroids). Thus, the term “chamber novel” is a reference to chamber music, implying an intimate setting, notwithstanding that, in theory, this work has no limits as to the forces (call it “symphonies of thousands” if thou wilt) that could be employed to do it justice.

While I am trained in music and not literature, I view myself as a literary dilettante. The term “professional composer,” on the other hand, is a virtual oxymoron as one would be hard-pressed to find any composers worth their salt nowadays who actually make a living from writing music (and, by this, I mean non-commercial composers of contemporary classical art music).

Jagdlied is, indeed, maximalist insofar as it offers the possibility of the inclusion of many musical and theatrical elements outside of the novel in and of itself. Writer Christopher Miller (author of Sudden Noises from Inanimate Objects and American Cornball) described it, quite accurately, as a Gesamtkunstwerk (most likely in reference to Wagner’s operas), which I took as a high compliment. While Jagdlied can simply be read in silence as a novel, the text, which I think rolls off the tongue rather nicely, is designed to be narrated to an audience in 240 separate fascicles (under ideal budgetary circumstances) and accompanied by music, pantomime, dance, cued audience participation, and even the partaking of carefully curated comestibles during its performances.

I have had a long career of shifting hats between composing and writing. Famous examples of writer/composers that come to mind are Anthony Burgess, Paul Bowles, Ezra Pound, and Friedrich Nietzsche. Less famous composer/writers I happen to know, who are exceptionally gifted in both idioms, are Lenny Cavallarro and David Post, and undoubtedly many others I haven’t heard of. It is almost impossible to be a servant to two masters, so I have had some long hiatuses in which I am engaged in one of those two activities but rarely both simultaneously. What inspires me, in all probability, is inertia. Namely: I burn out and need a change of pace and venue. Negative emotions are also a strong motivating factor (I seem to remember reading a quote by William H. Gass, “I hate therefore I write,” not to mention the idea, proposed by Alexander, of “literary revenge”). I tend to believe there is a disturbingly thin line between the motivation to artistic expression and criminal violence.

I have, BTW, dedicated the past several months to writing a new novel titled The At-Your-Beck Felicity Conveyor: A Novel of Sin & Retribution, which is scheduled for publication on 16 January 2025. For readers who may be interested, it is (at the time of this writing) available for pre-order from major book retailers such as Amazon.

GS: Elvis Costello once said, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” Can you reflect on this?

GLN: One of my composition teachers at Harvard (Pulitzer-prize-winning composer Donald Martino) once said something to the effect that the less said about one’s music, the better. I think what he meant is that talking about one’s own music demystifies the experience for the listener and I would tend to agree with him wholeheartedly. Perhaps this is something along the lines of what Mr. Costello meant in the quotation you cited.

GS: What are some of your favorite obscure words?

GLN: I have found that almost every time I “coin” a new word, I find out later on that someone somewhere has already used it. On occasion, this even happens with the titles of my pieces (many of which are quite quirky and even far-fetched). It is hard to say what my favorite obscure words are, as the English language is incredibly rich with thousands of examples of some real nuggets. There are words I coined on my own that I tend to use as a matter of course. One of my personal favorites is “stupinion” (meaning: a stupid opinion). A “surrealization” is the revelation or realization of something that is either absurd or impossible to imagine. “Aristobombastic” is self-explanatory. “Procrasturbation” is a word I “coined” on my own some forty years ago that has a rather obvious definition. As it turns out, not surprisingly, the latter has already been in official slang usage for quite some time, most probably long before I was around to dream it up inside my own personal bubble. I even came upon the word “procrasturbation” in one of Alexander Theroux’s books many years after employing it myself. Some “officially” coined obscure words that come to mind are “coinkydink” (coincidence), “kankerdort” (predicament), “scroach” (to scorch) and, of course, thousands of others. I can’t say I have any real favorites but I do feel quite strongly that all words worth their salt ought to be put to ample use by creative writers (contrary to what some eggheaded precisionists might argue), ranging from the archaic to street slang, specialist jargon, nonce-words, spoonerisms, and all the rest. I see words as tools of the trade for writers. It is very much the way I feel about harmony insofar as any dissonance, no matter how strident or arcane, can be explained in purely functional terms in relation to a key insofar as how it may ultimately be resolved or “explained” within a larger tonal context. The world of music is primarily dominated by “Little Jonny One-Chords” (i.e., those with one- to three-chord vocabularies who are clueless about basic techniques of voice leading, modulation, counterpoint, and so on) or by those who attempt to hide their ineptitude under the veil of experimentalism. I have witnessed composers who can’t write a tune to save their lives rise to prominence and, by stark contrast, composers of abundant talent who languish in neglect. It is a perfectly dismal state of affairs.

GS: Philip Glass claimed that music can change the feeling of an image but an image can’t change the feeling of music. Can you reflect on this? Do you think it’s true?

GLN: I think that what Glass says most definitely applies to the art of filmmaking. The vast majority of films have mediocre soundtracks that tend to decimate any potential value they may have as films. If a soundtrack is mediocre, formulaic, or unimaginative, I tend to lose interest in the film straight off. A bad soundtrack can make virtually any film lose its credibility while it is not difficult to imagine a mediocre film being transformed into a better-than-average film by a meticulously edited, well-crafted soundtrack. I think of a number of the filmmakers who are historically considered to be among the very finest (Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, Stanley Kubrick, Milos Forman, Lars Van Trier, Alfred Hitchcock, to name a few) in terms of their sharing in common the trait of being more sensitive than most of their peers apropos of the music employed in their films. Fellini’s films would be vastly diminished in quality without the music of Nino Rota (I seem to remember reading somewhere that Fellini himself had no real ear for music, which would indicate that he was unusually fortunate to have such a gifted musical collaborator); Stanley Kubrick greatly benefited from his appropriation of Ligeti’s music (albeit without the composer’s initial consent) in his film 2001: A Space Odyssey and, years later, with the composer’s consent in The Shining. Aside from its lush cinematography, Barry Lyndon is a far better-than-average film, largely on account of its carefully choreographed soundtrack. One thing that makes Milos Forman’s Amadeus such an outstanding film is, quite naturally, the music of Mozart (and even, believe it or not, the music of Salieri, for that matter).

I think Phillip Glass himself composed quite an effective soundtrack for Koyaanisqatsi, which served to make that film considerably more memorable than it would have been had no thought been put into its musical accompaniment.

GS: You told me you were pleasantly surprised by the complexity of the “Cloud Atlas Sextet,” a piece of music that started out as fictional before coming into reality through the book’s film adaption. Can you reflect on this piece more and also comment on the current state of music?

GLN: I remember that my Facebook friend, Russian-born composer Gene Pritsker, was involved in the music of the film based on David Mitchell’s novel Cloud Atlas (a film I have not yet seen). To refresh my memory, I just listened to three different versions of pieces employing that title. One of the tracks sounds like a rather simplistic “white-note” piano improvisation; another, which is labeled as the original motion picture soundtrack (or, quite possibly, a section thereof) is the one I remember you directed me toward at the time. Having listened to the music then and once again at the time of this writing, I remember my initial response to it being that it was in a lushly orchestrated quasi-post-romantic style, which had caused me to raise an eyebrow in recognition of its colorful orchestration and richer than average harmonic idiom, revealing the hand of a skilled composer (or composers?). I don’t know Gene Pritsker very well (I probably haven’t had more than two or three conversations with him on Facebook) but he is obviously a superbly gifted musician, as showcased by his “Cloud Atlas Symphony” in a performance by Kristjan Järvi and the MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony. Pritsker’s chops as a composer reveal themselves admirably in that particular rendition of the piece. I remember being initially impressed with the relative complexity of the harmonic language of the version you directed my attention to, which is a far cry from the run-of-the-nil, as harmony, according to what the late David Del Tredici commented on at the Bloch Festival in Newport, Oregon in 2002, is the single musical component toward which the vast preponderance of contemporary composers tend to be indifferent, generally taking a back seat to timbre and extended instrumental techniques (which, IMHO, are mere icing on the cake).

As for the current state of music, I could write a whole book on that subject. In a nutshell: there are some very fine composers operating on the periphery who remain hidden in the cracks, as they all too frequently tend not to be as adept at the game of self-promotion as many of their less skilled and less accomplished (albeit infinitely more “successful”) fellow travelers tend to be. The problem is often the question of how to spend one’s limited time and energy: honing one’s craft or promoting one’s wares. Rarely the twain shall meet in terms of fame matching talent. I can get into a lengthy discourse on the current landscape for composers of contemporary classical concert music, who are increasingly marginalized by the profit-driven streaming networks that force them to compete with pop musicians for their share of royalties and recognition. As composer Arnold Schönberg famously said, “If it is art, it is not for all, and if it is for all, it is not art.” It seems to be more and more the case that the talent scouts of yore are the “profit scouts” of the present.

GS: If you could score a novel, which one would you choose and why? What would the music sound like?

GLN: As I indicated above, I have already attempted to do just that with Darconville’s Cat in my trio for flute, viola, and cello (Op. 52). The piece is in a chromatic tonal language, with tango motifs and hints, perhaps, of Der Rosenkavalier thrown in for good measure.

As it turns out, at the time of this writing, I just completed a farcical mini-soundtrack as a complement to my latest novel The At-Your-Beck Felicity Conveyor, which can be heard here.

As far as other novels go, I honestly don’t know what I’d choose. Crime And Punishment comes to mind as one possibility; such an undertaking, however, would only be possible if supported by a commission fee that would feed and house me and pay for all my other living expenses for the time it would take to complete such a formidable task. The late Russian composer Eduard Artemyev scored Dostoevsky’s novel into a very effective “rock opera.” The composer’s son Artemiy sent me a rare and beautiful recording of that work some fifteen years ago.

On that subject, I have asked Alexander Theroux to write me a short libretto (perhaps a thousand to two thousand words) that I could set to music (say, for three to five opera-singing thespians and a small chamber orchestra), for I have been itching for many years now to compose a short opera (perhaps half an hour or so in length). Some years ago I was approached by a writer-cum-librettist who wanted me to collaborate with her on such a project. Although I was open to the idea, I wasn’t terribly motivated by the libretto she had in mind nor by the fact that there was no guarantee of any remuneration. If I were to write an opera, I would want, of course, to feel some enthusiasm for the text I was setting, in which case I would do it for free. I know Alexander is incredibly busy with his novel Herbert Head, among other projects, but I feel a compulsion to give him a gentle nudge once again with the aforesaid proposition.

GS: What’s an instrument you’d like to learn or use that you haven’t had the opportunity to?

GLN: In a perfect world (and life) I would play many instruments. Piano is my only instrument and I have reached an age where it would be impractical (even silly) for me to learn to play other instruments. When I was younger I wanted to learn violin. I had lessons for a few months but didn’t have the time to pursue it seriously at the time. At this point in my career, I am less interested in playing and more interested in devoting the remainder of my years to creative projects as both a composer and (oddly enough) a writer of plays and fiction. I take my cue from György Ligeti who, at the historic performance of his Etudes by pianist Volker Banfield at Hertz Hall on the U.C. Berkeley campus on 29 January 1993, when asked by an audience member if he was able to play the Etudes himself, answered something to the effect that there would be no point in his playing them as the featured pianist could play them considerably better than he could.

GS: What book have you read and think deserves more readers? Why?

GLN: That’s not a difficult question to answer when speaking of Alexander Theroux’s works, in particular Darconville’s Cat, Laura Warholic, and his recently published collections of short stories, fables, and truisms, for they are, inarguably, some of the most underrated books by one of the most unduly neglected of all living writers. Aside from the obvious answer, I am not sure I can answer your question so directly regarding literature, as I haven’t ventured into “unexplored” terrain as much in my reading as I have in my listening. While I admire the writers whose musical portraits I have composed, many of them are relatively well-known. The playwright David Hirson is one writer who comes to mind. His play “La Bête” is an incomparable comic masterpiece, undoubtedly one of the great plays of the 20th century, written very much in the vein of Moliere with its masterful rhyming couplets from beginning to end. Aside from the sheer technical virtuosity of his writing, the play itself is brilliant on so many different levels.

There are, likewise, many composers who are severely underrated whose music, IMHO, deserves considerably more attention than it receives. Permit me to share a few of those names for your readers: Joseph Fennimore, Gottfried Von Einem, Tison Street, Henry Martin, Arne Oldberg, Ernst Toch, Ladislav Kupkovic, Alfred Watson, Victor Steinhardt, Uri Caine, Derek David, Noam Elkies, Hsueh-Yung Shen, and (notwithstanding their relative fame) Frederic Rzewski, George Rochberg, Paul Schoenfield, Tomas Svoboda, and David Del Tredici. Even among the more “mainstream” historically recognized composers, there are specific works by some of them that ought to be given considerably more attention. Hugo Wolf, for example, who is best known for his Lieder, wrote some of the finest works in the literature for string quartet that I know of, in particular his little-known “Intermezzo,” an absolute jewel of a piece that is rarely played, notwithstanding that it was many years ahead of its time. Ernst von Dohnanyi is a first-rate composer treated, historically, as a second-rate composer due, most probably, to his formidable reputation as a pianist. The Russian composer Sergei Taneyev, who is rarely heard in the U.S., wrote, arguably, some of the finest chamber music in the literature. I was one of the first kids on my block to recognize the genius of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, whose reputation was damaged when he was forced into exile from Vienna at the time of the Anschluss to compose music for Hollywood films. Due largely to the efforts of his granddaughter, Katy Korngold Hubbard, who lives right here in Portland and runs his estate, Korngold has become a household name among musicians and his music has happily found its way into the musical canon.

In any case, lack of recognition is a universal problem for many great artists in both literature and music, especially if they are afflicted with a condition known as “anorexia of the charisma.”

GS: Aside from your own work, what piece of music would you want to act as your epitaph? Why?

GLN: Of course, many of the works I think of would be impractical to act as epitaphs if they were to be performed, say, at a memorial service. The cost of hiring qualified musicians to do so would be prohibitive. There is an ongoing custom for composers to have memorial concerts of their own compositions performed within a year or two following their deaths. Such events tend to be especially sad and depressing when one realizes that it is quite often the case that the composers being memorialized in such fashion are experiencing their allotted “fifteen minutes of fame” posthumously. There’s an old riddle I once heard attributed to Max Reger: “What do composers and pigs have in common…? They are both enjoyed after they die.”

Although it would make little sense in any way, shape, or form to have any music other than one’s own functioning as an epitaph, if one is a bona fide composer, I will attempt to answer this question as best I can. The first piece that comes to mind, perhaps, is Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings or, perhaps, his better-known Four Last Songs, both of which have a stately, somber, elegiac quality that makes them deeply moving. The Adagietto movement from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony was famously conducted by Leonard Bernstein at the funeral service of Robert F. Kennedy in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City on 8 June 1968, two days after he died from being shot. There are other slow movements in Mahler that could also serve such a purpose quite well. A less beaten path in this regard would be Gottfried Von Einem’s Nachtstück for orchestra, Op. 29, the Lento Religioso movement from Korngold’s

Symphonic Serenade, the Transcendental Variations from George Rochberg’s Third String Quartet or, perhaps, his Ricordanza for cello & piano. Another work that comes to mind is Schubert’s Nonet or the Adagio (second movement) of his String Quintet in C (D. 956, Op. Posth 163), the piece that pianist Arthur Rubinstein said he wanted to hear before he died. A more practical work to perform would be Contrapunctus XIV from J.S. Bach’s The Art of Fugue, which, left unfinished by the composer before he died, trails off into infinity. Gesualdo’s Moro Lasso (from his sixth book of madrigals) also comes to mind. There are movements from the late quartets of Beethoven that could also suffice for that end. I have composed some pieces that would suit me quite well for my own “epitaph,” such as the ninth movement of my Second String Quartet (Op. 32, No. 9) or my setting of Eduard Möricke’s poem Verborgenheit (Op. 1, No. 11). It is still one of my ambitions to compose a searing Adagio movement in this time-honored tradition. My good friend Ernesto Ferreri is one of the few American composers I know of who has composed such a work. Everyone seems to cite the Samuel Barber Adagio for strings as the piece of choice in this regard but I would beg to differ, as such a piece, nice and pleasant though it is, simply doesn’t pass muster when measured against Strauss, Mahler, Bruckner, Korngold, Brahms, Schubert, Mozart, Bach (e.g., the Dona Nobis Pacem from his B Minor Mass!) and his other European counterparts. Even John Adams recognized this relative lack of appropriate music with the necessary gravitas for memorializing catastrophic events such as September Eleventh by American composers, who often have a tendency to sound either unrealistically optimistic (what I tongue-in-cheekly refer to as “Genericana”) or whose fashionable nihilism sounds utterly postured and contrived. That might explain why Bernstein had no choice but to conduct Mahler at RFK’s funeral.

The answer to your question “why” is that the above-cited works are, quite arguably, amongst the greatest tear-jerkers ever composed. Some of your readers might think me unwholesome for proposing such funereally morbid or bombastically “pretentious” works that are prohibitively expensive to perform (that is, if one is intent upon doing them justice). Unless I’m mistaken, there seems to be an American tradition of singing nursery tunes at funerals. For me, silence would be preferable.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as editorial services, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Acclaimed composer Gary Lloyd Noland (who goes by the nom de plume Dolly Gray Landon as a writer of plays and fiction) was born in Seattle in 1957 and grew up in Berkeley. As an adolescent, Noland lived for a time in Salzburg (Mozart’s birthplace) and Garmisch-Partenkirchen (home of Richard Strauss), where he absorbed a host of musical influences. Having studied with a long roster of acclaimed composers and musicians, he earned his undergraduate degree in music from UC Berkeley in 1979 and his graduate degrees in music composition from Harvard in 1989. Noland’s catalog consists of hundreds of works, which include piano, vocal, chamber, orchestral, experimental, and electronic pieces, full-length plays in verse, “chamber novels,” and graphically notated scores. His award-winning 77-hour-long Gesamtkunstwerk, Jagdlied: A Chamber Novel For Narrator, Musicians, Pantomimist, Dancers, & Culinary Artists (Op. 20), was listed as the Number One Book of 2018 by Amy’s Bookshelf Reviews. Gary resides with his wife Kaori in the Portland, Oregon, metro area. You can preorder his latest novel, The At-Your-Beck Felicity Conveyor, here. You can purchase his CDs here.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.