“I once wrote a line for a character, ‘Everyone I ever loved is either dead or deported.’”

— James McCourt in response to the poem “Revelation 03/10/2022” by Blake Millwood

GS: With your 1975 debut novel Mawrdew Czgowchwz in mind, can you tell me who are some of your favorite opera singers? What about specific performances you’ve attended?

James McCourt: Hundreds of performances over so many years, and a list of Favorite Singers as long as Leoporello’s as sung to Donna Elvira, over which hovered always the two great singing musical geniuses of the age, Maria Callas and Victoria de los Angeles, each of whom regarded the other in the highest degree, Maria saying of Victoria, “She is the one rose in so many weeds.” (A rather strong statement contrasting Callas’ often bitter feelings about other sopranos: for instance she said of Joan Sutherland, referring to the latter’s assumption of many of the former’s bel canto roles, “She has undone all my work.”) As to Victoria, who proclaimed, after Maria’s death, “Nobody could touch her,” this statement came about in conjunction with a late occasion friendship brought about by a gesture of Callas and by her illness in retirement—Victoria saying later, “I was always trying to get her to keep the heart up.”

I never knew Maria personally, although I did have a lovely note from her following the publication of Mawrdew Czgowchwz, but I did hear her at the Metropolitan and once at Carnegie Hall in a glorious, knockout concert performance of Bellini’s Il Pirata. As for Victoria, after a long “apprenticeship” starting in my teenage years, there developed one of the greatest relationships of my life with a woman of the most phenomenal personal qualities imaginable. She is with me every day since her death.

GS: From your first novel to your latest, 2007’s Now Voyagers, it’s no secret that you love baroque, maximalist prose. Where does this fascination stem from and is it to any degree an answer to, if not an attack against, what Steven Moore calls “thin-blooded minimalism”?

JM: Well, about the idea of “maximalist,” after Beckett, what do you do, give up? Reading him, going to the plays whenever you can, reading all the critics, understanding where in his life the waiting and the anguish came from (the Maquis), the terror of the supposedly complacent 50s…what do you do? If you can’t go on, you don’t go on like he did, you go off. Therefore, what? For me it got to be that I couldn’t think of a single thing not to say—about them—they who took up room in the mind. Both my parents had a lot of friends, both separately and jointly, and a lot of opinions about them. There were also a lot of parties at home, a lot of “open house” occasions in which my mother played the piano and people sang—my father’s specialty was “Some Enchanted Evening” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, sung as well as Ezio Pinza, and my mother and older brother would do the duet, “You’re Just in Love” from Call Me Madam, Iirving Berlin’s vehicle for Ethel Merman.

Then, too, my mother spent a lot of time on the telephone, keeping up with friends she had gone to grammar school and high school with, with her club work, etc. And many of these women came to dinner, three of whom in particular became additional (sometimes alternate) mother figures for me. All through my childhood there was music, everywhere on the radio—opera broadcasts from the Metropolitan on Saturday afternoons, from Carnegie Hall, on the radio, and collections of records—78s, 45s , LPs, first monaural, then stereo. I got a two-reel tape recorder and recorded the Top of the Pops for our high school crowds parties, and naturally, everybody in high school gossiped and talked about sex—talked about sex. Also we all knew what was playing at the Roxy, at Radio City Music Hall, and every other picture palace within reach. Then came the Broadway theater and the opera. On the standing room at the opera, gossip reached the high baroque—every scrap about every singer’s life that could be scraped up was dished, and then the function of visits backstage to the diva dressing rooms was essential to life—not just life in the audience, but to life. To get into Maria Callas’ dressing room was but one of the very big deals. The divas were much more comfortable and given to deep dish with us than ever to interviewers—which was strange, I used to wonder, did they not think their every remark would spread all over town (the town of opera, New York of course being the opera town, second to Milan (La Scala) only in terms of opera’s history, not in terms of opera “fabulosity.”) Then too, think of the effect on an already “saturated” writer, of opera itself, of the overwhelming nature of the experience, and add to that four years of intense education in the entirety of Western Civilization, its history, philosophy, literature, and fine arts, a double major in English and Modern Languages (French, German and Italian), and there is a writer ready either for a nervous breakdown, a serious academic career, or a roll of the dice in fiction writing—writing about a lot of things that happen to a lot of characters. This is called enlistment.

GS: Speaking of Now Voyagers, the book’s full title is The Night Sea Journey: Some Divisions of the Saga of Mawrdew Czgowchwz, Oltrano, Authenticated by Persons Represented Therein, Book One. I’m sure readers are wondering where the second and third books of the trilogy are. Are you still working on these volumes?

JM: Having finished Part Two of the Mawrdew Czgowchwz saga (called “Epiphany”), I’m trapped in the world of “Winter Journey” and “Spring’s Awakening.”

GS: You’ve mentioned that, early in your life, you wanted to be an actor, and you even studied briefly at the Yale School of Drama. Assuming you could choose any, what would be your ideal role?

JM: At Yale, I’d like to have played Konstantin in The Seagull. Later on, Hickey in The Iceman Cometh, and James Tyrone the Younger in Long Day’s Journey into Night—until we saw Philip Seymour Hoffman in the role, which put paid to that notion. How great he was beggars description….

GS: Can writing fiction be a kind of method acting? Is this something you’ve done to one degree or another?

JM: Method acting. Interesting question you’ve picked up on, because indeed, having studied Stanislavski at Yale, I adapted the skills in teaching writing years later at Yale and then again at Princeton, asking students to get their characters to answer the “four questions” essential to the method: Who am I? Where do I come from? What do I want? Where am I going? Then to work out the themes of sense memory and emotional recall in relation to these questions—not making the characters necessarily tell the readers the details of such researches, but imbuing the characters with personalities that emerge from the research. Also to let showing not telling prevail in the third person narration.

GS: On her deathbed, your mother instructed you to “tell everything,” which resulted in Lasting City: The Anatomy of Nostalgia. What’s one memory in that book you’d like to relive if not remember forever?

JM: I think my mother’s death and the cab ride downtown, ending with the talk with the waitress at Howard Johnson’s and the memory of the archetypal waitress Rhoe (a prominent character in the later Mawrdew Czgowchwz stories): she was the waitress at Burger Ranch, across 40th Street from the Old Met.

GS: What’s the most important thing that has happened in your life since the events narrated in Lasting City?

JM: It’s the same thing that happened before…that and the memory of my great friendship with Victoria [de Los Angeles].

[McCourt, writing for the Los Angeles Times in 1994: “The dark diva with the gloriously soulful eyes, whose image illuminated the closing ceremony of the 1992 Olympics, has just turned 71. The city of Barcelona turned out in force to celebrate De los Angeles’ 50th year on stage, one of the longest careers in the history of opera. In 1944, she made her professional debut at the Palau de la Musica, where, last May, the crowds covered her with carnations and swathed the stage in bouquets when she finished her recital. She is one of the most beloved of opera stars, the last surviving working diva of the golden age of the first LPs, the fabulous ‘50s, when technology was content to record the truth of voices without resort to electronic enhancement.”]

GS: The Big Apple plays an essential part in most if not all of your work. In a word, what did New York City mean to you then and what does it mean to you now?

JM: Well, it means just about everything. I was born here, went to school here. I’ve lived here most of my life—there were four years in London and many years going and coming back from dreadful Washington, and then there was the year at Yale where I met Vincent and we skipped out of the country for the big European adventure. My mother always said, “If it ain’t New York, it ain’t.” Her family had come from Dublin to Philadelphia in 1730, then in 1865 to New York, my father’s from County Tyrone to New York in 1830, so we were pretty established New Yorkers by the time I was born.

GS: What is a novel you’ve read and think deserves more readers? Why?

JM: The best novel I can think of that deserves canonical status is Harold Brodkey’s The Runaway Soul. Only fools deride it, starting with David Bromwich, whose review seethes with unacknowledged envy.

[In his review, Bromwich writes, “The book is someone’s argument with himself—a wrangle of unharmonizing perceptions. He can make an early self-portrait out of a few geographical and physiognomic facts, and then say uncozeningly: ‘If I loved you, this is the creature who would love you.’ There is distance in those words, as there is in: ‘Part of what I look like is that I am the person who has had my life.’ At the point where narcissism can turn into a compulsive desire to charm, something goes cold in this author. Few readers will love him. Still, it is, with him, a point of artistic honor not to strive to be lovable.” And later: “In some novels of comparable scope you are lost if you fail to read every word. With The Runaway Soul, you are sunk if you try to read every word. The author seems often in a race with himself, but at the same time to be watching the race, and the consequent motion is a ponderous jumble of legs. And yet a certain consistency, partly repellent, partly memorable, does emerge from the deliberate mess of imprecision. The psychology of the hero and the texture of the writing are as continuous as a cocoon.”]

GS: You and I connected when I saw that a James McCourt commented on a contributor’s essay at The Collidescope, and it turned out that it was the James McCourt. Your comment took issue with the contributor’s use of “disinterested” instead of “uninterested.” What are some of your other pet peeves, grammatical or otherwise?

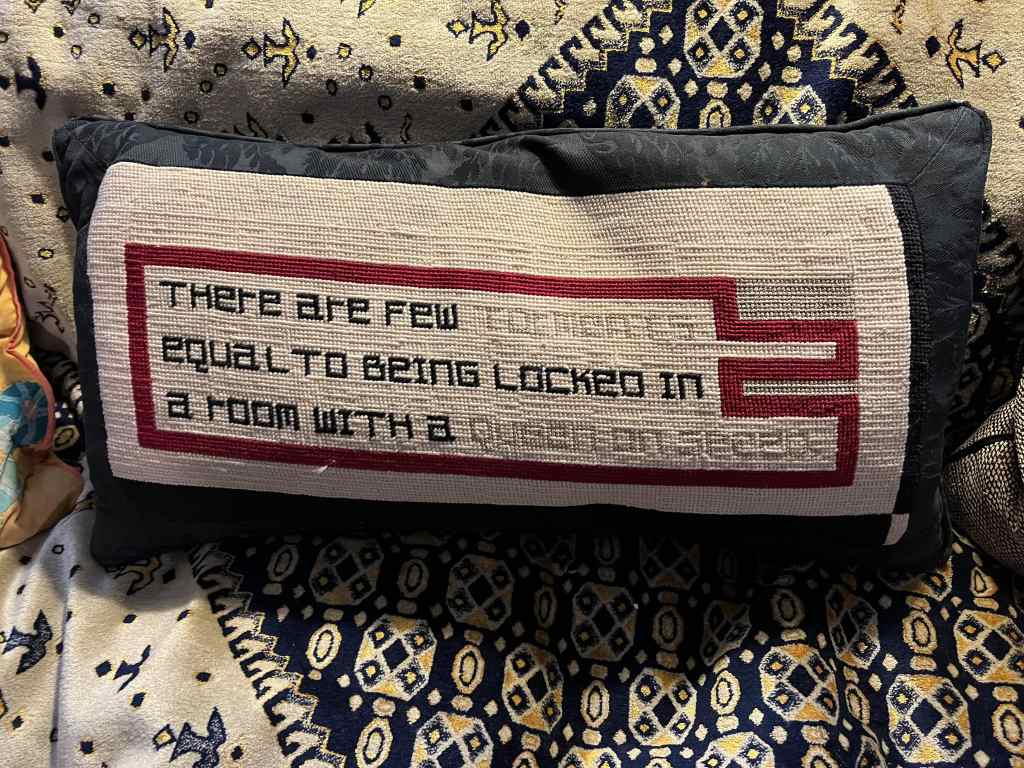

JM: My biggest pet peeve is the use of the nominative after a preposition: “with he and I,” “when my mother said to my brother and I,” etc. That and of course, “lay” for “lie, which is used by supposedly educated news writers, and “Me and my brother” for “My brother and I,” but the correct use of this one has come to make people think you’re being pretentious. Then there’s the misuse of “hopefully,” but I’ve been called out for this one by someone who believes that if “hoffentlich” is correct German in said use, then “hopefully” is correct in English—but I’m not sure hoffentlich is in fact correct in such a way in the German. As the great Japanese grammarian Sosueme says, “Who gives a rat’s ass?”

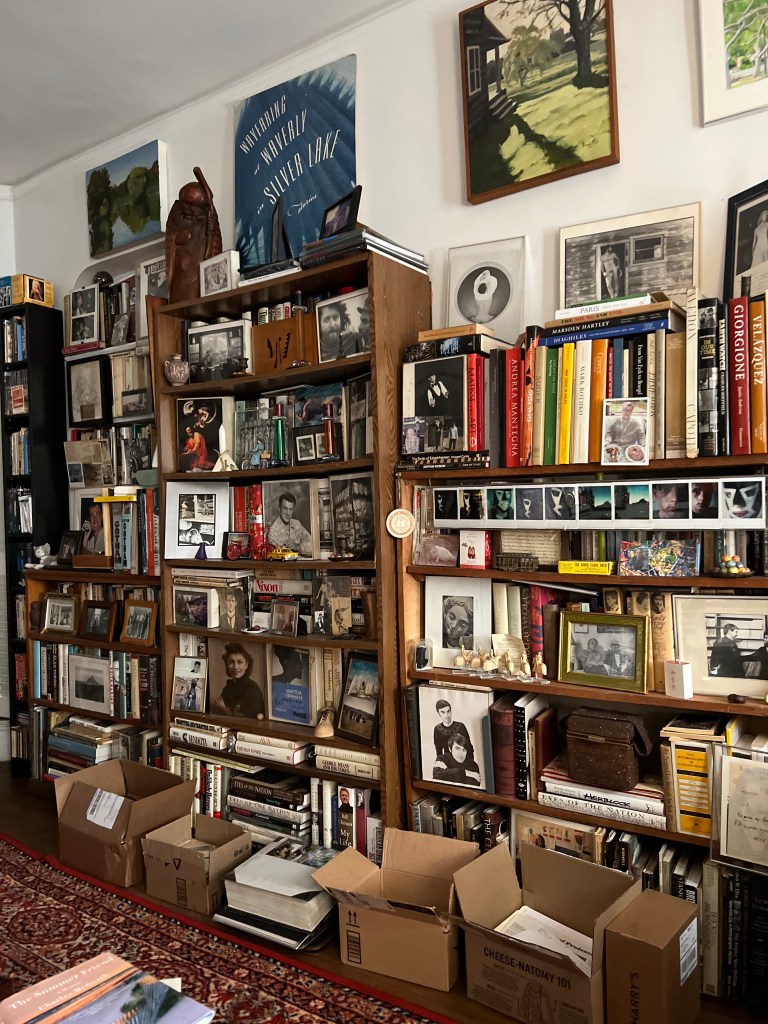

GS: You’ve been with your partner, the writer Vincent Virga, for about 60 years. Do you take part in each other’s creative processes? If so, in what ways?

JM: Vincent and I never go near each other’s work until it’s finished—at least the first few drafts, although he often tells me in a narrative way what’s up. For my own part, I’m always unsure and therefore I suppose you could say withholding—and I’m forever revising and changing, whereas he’s able to go in a straight narrative line, whereas I’m constantly diverting from the plot (I call it Brodkey-itis).

GS: What are your thoughts on gay issues in America in contrast to the past?

JM: I tend to leave “gay issues” to the new generation who seem to have little enough interest in the 20th Century. After “Queer Street” and “Lasting City” I have withdrawn—although this is perhaps not a polite answer in the light of the projected 2025 reissue of Time Remaining. [The reissue appeared in April, 2024, from the Library of Homosexual Congress]

GS: You knew Gilbert Sorrentino.

JM: Yes, I had a nice correspondence/friendship with “Gil” while he was at Stanford, begun by his kind appreciation of my Time Remaining and continuing until his far too early death. It had been a keen boast of mine to have published my first story in New American Review #13 (lucky number for me) along with his “The Moon in Its Flight,” a beautiful lyric prose poem.

GS: Is it truly not over until the fat lady sings?

JM: I suppose it’s not over for me until she does—I’m probably thinking of Eileen Farrell belting out a number from the Other Side.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as editorial services, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

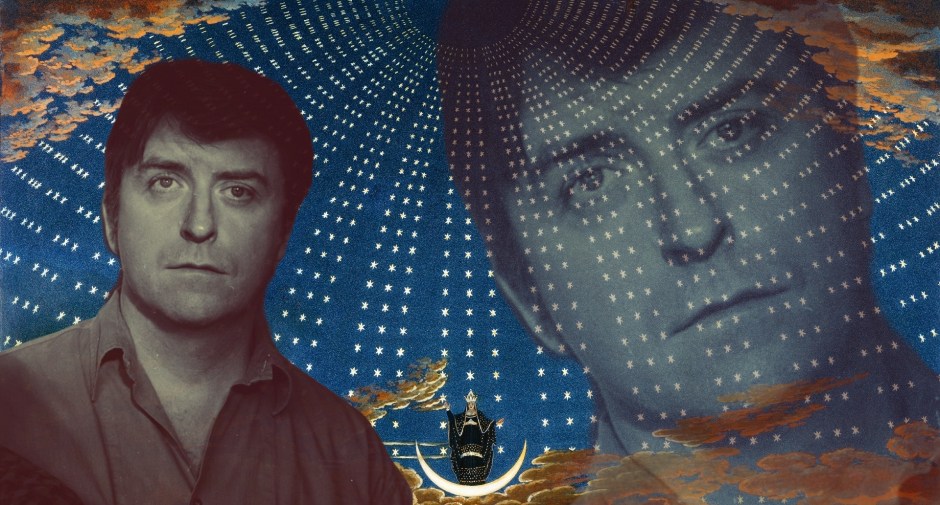

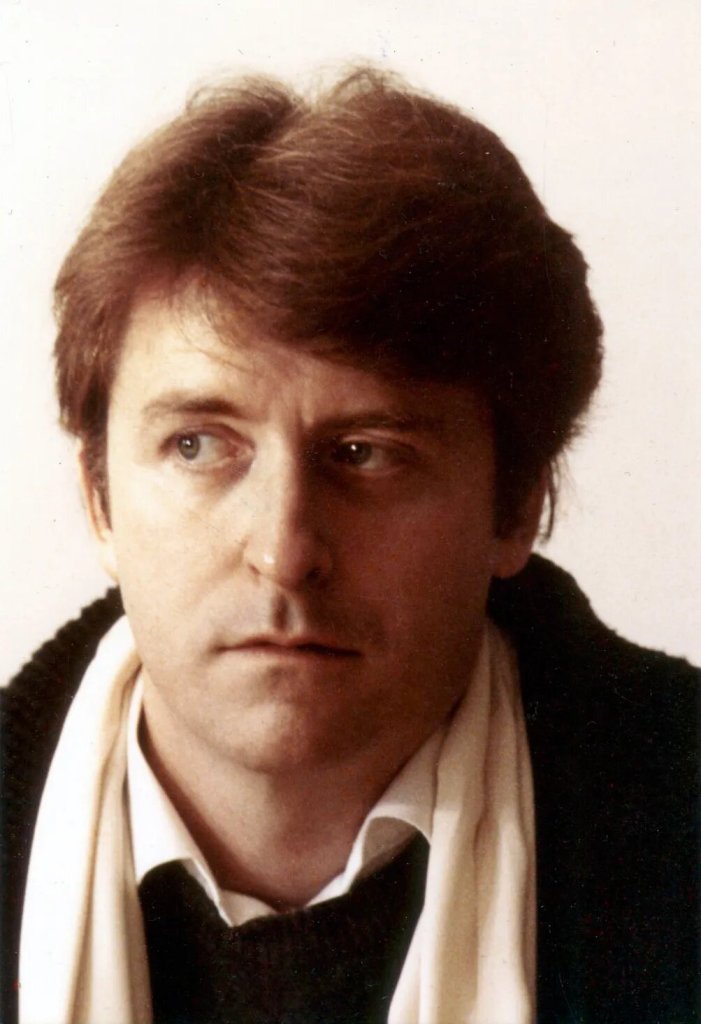

James McCourt is a gay American-born writer and novelist who was raised in Jackson Heights, Queens. McCourt has been with his life partner, novelist Vincent Virga, since 1964 after they met at Yale University as graduate students in the Yale School of Drama. McCourt is the author of Mawrdew Czgowchwz (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1975), Time Remaining (Knopf, 1993), Delancey’s Way (Knopf, 2000), and Now Voyagers: The Night Sea Journey (Turtle Point Press, 2008), among other books. He has contributed to the Yale Review, The New Yorker, and the Paris Review. He lives in New York City.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.