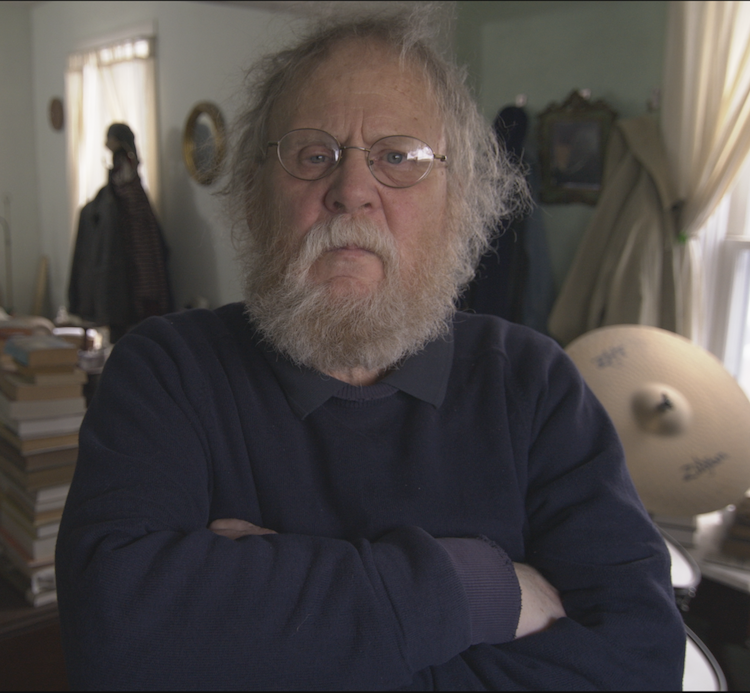

About Dow Mossman: He received his B.A. from Coe College in his hometown of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. In 1969, he earned his MFA from the University of Iowa’s Writers Workshop, only twenty miles away. After winning several awards for his fiction, including a Book-of-the-Month Club Fellowship, Mossman completed The Stones of Summer in 1972. Ten years in the writing, the novel was heralded as the debut of a major new talent, and the book’s style and content were compared by critics to James Joyce, William Faulkner, Malcolm Lowry, and J.D. Salinger.

Mossman then disappeared from the publishing world entirely. As the subject of Mark Moskowitz’s Slamdance award-winning documentary, Stone Reader, The Stones of Summer was rediscovered and republished by Barnes & Noble in 2003. Mossman still lives in Cedar Rapids.

I interviewed Dow Mossman here.

“‘I wish to worship at the wood’s heart, the stone’s eye, the language found forming forever in the swaying cranes of the trees.’”

The Stones of Summer by Dow Mossman is a Great American Novel. I’ve forgone the definitive because America boasts too rich and complex a history to contain in a single tome, even when the first Great American Novel, Moby Dick, plumbed both the mysterious seas’ depths and the heavens’ highest heights. Still, Melville didn’t net the empty glitziness of materialism found in Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, the manic madness of politics and fear as played out in Robert Coover’s The Public Burning, the biblical fever dream that never ends across almost 1,200 pages in Miss Macintosh, My Darling by Marguerite Young, the road trip anti-romance of Nabokov’s Lolita, the darkly nuclear omnipresence of Underworld by Don DeLillo, and David Foster Wallace’s addiction-addled estuary of the pre- and post-Internet Age known as Infinite Jest—Great American Novels all. How does Iowan Dow Mossman’s novel fit in this national pantheon? His is a magical realist bildungsroman like no other, vibrating with the loss of innocence and meaning in an America melancholized by time tides and far-off war.

Although it’s all too easy to take Moby Dick’s place in the canon for granted, let’s not forget (as if remembering ever prevented history’s repetition) that the novel went under upon its publication in 1851, like one of Melville’s own enigmatic Sulphur Bottom whales whose “brimstone belly” scrapes “the Tartarian tiles” of the ocean floor and is seldom seen, only to surface in full force some 70 years later thanks to championing from literary figures, such as biographer Raymond M. Weaver and critic Carl Van Doren. Think about this. The novel of the white whale and the hateful Ahab, so ingrained in our culture now that it has reached the status of mythology (something that only comes around once in an Ancient Greek civilization), was forgotten for almost a century. This should tell you two things in particular: 1) critics and readers are often whiny swine before pearls, and 2) there are likely many more forgotten great novels out there, American or otherwise, assuming they’ve managed to get published in the first place.

After The Stones of Summer was published in 1972, Mossman had an early cheerleader in John Seelye, who wrote in the New York Times one of the only reviews of the novel. Yet so fickle is fate and so micro the attention span of the public that something as seemingly inconsequential as the lack of a front-page review made all the difference in making no difference at all. Despite Seelye’s praise, in which he wrote, “Reading The Stones of Summer was crossing another Rubicon, discovering a different sensibility, a brave new world of consciousness. The Stones of Summer is a holy book, and burns with a sacred Byzantine fire, a generational fire, moon‐fire, stone-fire,” Mossman’s novel fell on blind eyes and went out of print.

Almost three decades later, enter filmmaker Mark Moskowitz. At the brink of a new millennium, Moskowitz released his Stone Reader, a beautiful, obsessive, and even floral-cozy documentary about his love of reading and an unknown book titled The Stones of Summer. The film charts a discursive pilgrimage in which Moskowitz tries to hunt down the forgotten author, encountering various personages in some way involved with the book, such as original reviewer John Seelye, William Cotter Murray, who was Mossman’s professor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and even the book’s cover artist John Kashiwabara, who barely remembers doing the job. Any bibliophile would do well to seek the film out as a love letter to reading with utmost passion if not as a kind of visual preface to the book in question. I related to Moskowitz’s high degree of dedication and enthusiasm, having gone on two particularly special pilgrimages myself, the first to meet the nonagenarian Women and Men author Joseph McElroy in Manhattan and the second to meet the octogenarian Darconville’s Cat author Alexander Theroux in Cape Cod, both trips proving wrong the old adage warning against meeting one’s heroes, which is not to say that William Gaddis wasn’t right when he called artists the dregs of their work, the human shambles that follow it around, something true of us all.

One scene from Stone Reader has stayed with me in particular: When Dow Mossman’s former agent Carl Brandt learns that Mossman worked as a welder for 19 years after the commercial failure of his magnum opus and then became a graveyard-shift paperboy while taking care of his dying mother, Brandt almost seems on the verge of tears and says, This is what we do to our artists in this culture.

It’s true that Stone Reader became an award-winning cult sensation praised by Roger Ebert and turned Dow Mossman into a celebrity overnight. Most importantly, it led to a Barnes & Noble reprint of The Stones of Summer that, as it happens, features a blurb from Joseph McElroy, “What a trip, what a testament from the Fifties and Sixties, this life-risking romance with excess and aspiration, defeat and ravishing insight, our maddening American past and its landscape of lies, laughs, talk, paralysis, rebirth, stony metamorphoses into danger and beauty and story….” Still, over twenty years on from that resurgence, the book is hardly known or read to any Moby Dick degree. I do take solace in the fact that Barnes & Noble printed so many copies that I often see at least one in used bookstores from New York City to Asheville (something Mossman was pleased to hear, as the latter city is the home of his literary hero Thomas Wolfe, a fellow “putter-inner”).

To embark on anything even approaching the status of a Great American Novel is something akin to insanity, a fool’s errand to the fullest. Borges said as much when he wrote, “Writing long books is a laborious and impoverishing act of foolishness: expanding in five hundred pages an idea that could be perfectly explained in a few minutes. A better procedure is to pretend that those books already exist and to offer a summary, a commentary.” Yet how would literature fare without Borges’ fools? Readers would be reduced to the delusional and indirect, satisfied with Hemmingway’s hums and Carver’s scratches, the pricks and pinholes of something vaster, rather than diving headlong into the divine and depthless sea of dreams proper. Still, whether out of outright egoism, love of language, an attempt to prove something, to reach beyond himself, or, more likely, all of the above and then some, Mossman dedicated himself to a decade-long impoverishing act that has made its readers all the richer for it even if the Herculean task led to a hospitalization stint for the author because of a nervous breakdown. The work, stretching from 1949 to 1968 (or 1942 to 1969 if you go by the “Yeoman’s Notes” subtitle that was removed from the B&N reprint), is made even more amazing for being a debut novel. Seelye touched on this in the opening of his seminal review, “The Stones of Summer cannot possibly be called a promising first novel for the simple reason that it is such a marvelous achievement that it puts forth much more than mere promise. Fulfillment is perhaps the best word….” Indeed, “first” or “debut” are, in essence, misnomers, for The Stones of Summer is an ultimate novel, more so than those sole ones written by Salinger or Lee (and no, Go Set a Watchman, that early manuscript, doesn’t count).

Dow Mossman mentioned that he nearly titled his book The Stones of Summers plural, a fact that reminded me of how Salman Rushdie wrote down the working titles The Children of Midnight and Midnight’s Children alternatively until he settled on the only possible choice. In Mossman’s case, a summer singular evokes an infinite season if not an all-encompassing entity thereof, eternal and plural within, as immortal as the preceding stones, which are landmarks, airmarks, fleshmarks. Yes, The Stones of Summer is a title as lapidary as any dreamed up by the Latin Americans: One Hundred Years of Solitude, An Invincible Memory, Terra Nostra.

Not since Ray Bradbury’s equally estival Dandelion Wine have I read anything so suffused with nostalgia and wonder, with a pure zest for life, although this is more true of the first of Dow Mossman’s three sections, “A Stone of Day,” in which he writes about his stand-in protagonist Dawes Oldham Williams’ childhood, one of visits to his greyhound-breeding grandfather and an alluring yet somewhat antagonistic family friend-cum-spinster named Abigail Winas, as well as escapades alongside Ronnie Crown, a rebellious neighborhood kid. Both Mossman and Bradbury write with a purpureal intensity, yet Mossman takes it further, entering the realm of the surreal, as mentioned earlier. It’s not so much that Mossman is writing about events of sudden fantasy, as with other rare examples of American surrealism, namely Lewis Nordan’s Wolf Whistle or Daniel Wallace’s Big Fish, but the prose itself forms an oneiric patina that colors the majority of the novel like the stained glass of a peculiar cathedral.

Some examples: “He sat watching, there, in the rain dark as spies falling,” which brings to mind René Magritte’s Golconda, “She was light’s water, its prism, its only river,” a pony’s “nostrils steamed like God,” “the conversations inside the car were like great wood eyes,” an old man’s cane “was coughing,” “a silence like screaming roses growing in glass houses,” and “Often, to Dawes, it seemed his father had moments when he suddenly should have flashed forth a head of gold, leering teeth like operas when he smiled.”

Such imagery is a consequence of Mossman’s emphasis on language, the author conceiving the work as a “narrative poem” or “mock epic” of the Midwest, lending the novel a grander scope than most writers dare to imagine. While this reader could have spent forever with little Dawes’ conception of shamanistic summer’s shenanigans, the initial section must come to an end as inevitably as the season itself, the novel going well beyond Dandelion Wine’s sphere. Part one closes with Dawes “missing already the dead voices of other summers,” and the feeling of an open world closes in on itself, giving rise to pubescent pessimism and plenty of alcohol in part two, “Stones of Night.”

Not all is lost, for Dawes occasionally indulges in an acute sense of romanticism via Becky Thatcher and later the aptly named Summer Letch, self-fulfillingly failed though it is: “He would never let anything touch him again. He would steel himself against the world, locking it out. He would surround himself with himself.” Yet such failure is nothing compared to the automotive tragedy involving Dawes and his posse at the section’s end.

Part three, “The Stones of Dust and Mexico,” is comprised of what Mossman calls “three levels of chaos.” Tristram Shandy is mentioned multiple times in this part, which could help explain some of its non-traditional and metafictional structure. A decade after the tragedy, a deeply despondent and irrational Dawes finds himself in Mexico, à la Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. The chaotic and atemporal structure also reflects Dawes’ state of mind, in which he verges on schizophrenia while trying to work on his writing, excerpts of which punctuate the section and almost blend with the overarching narrative. “Ten years have passed. You must remember that. You must remember it because I can’t any more [sic]. You must remember it because the bastards have taken myself away with them. Ronnie Crown was right; they beat you in the end. Because I am not me any more. I am no one.”

Parents are as gods from the perspective of children, yet that divinity gets stripped away year by year, mistake by mistake, especially when “growing up seriously absurd,” as Mossman put it via Paul Goodman, and the climax of Mossman’s novel sees Dawes retreat to his parents’ home to evade the police after a vicious bar fight. Far from gods in his bloodied eyes, Dawes excoriates his makers in a scene of Promethean betrayal devoid of empathy. Rather than life-lust or aching hope, what we are left with is a foreboding confirmation of inevitable atonement.

It’s only natural to wonder why Mossman never published another book. Near the end of John Seelye’s review, he writes, “Dow Mossman’s novel is a whole river of words fed by a torrential imagination, and such a source is not likely to stop flowing.” Despite not publishing so much as a short story collection, Mossman’s imagination indeed continued to flow. He told me he should have written a basketball novel and a speedway novel. Not long after The Stones of Summer, there’s evidence (in a letter to his former editor) that he also made substantial headway on a novel called Fossil Fuels. And he has journals upon journals that feature his poetic lines. During phone calls with Mossman, it can be difficult to get a word in because he’s still bursting with stories and opinions, including a DeLillo-esque conception of American politics. Still, make no mistake, The Stones of Summer is very much a river, as Seelye put it, and whether readers wade or drown in it now or later, it will never stop flowing, a river in a forest where even unheard trees continue to fall.

In fact, after I told Mark Moskowitz about the novel I was working on at the time, the nearly half-a-million-word Morphological Echoes, he said, “Your epic gives me fond memories of perusing Dow’s full 1,200-page manuscript for Stone Reader, and seeing editor markups where [Betty Kelly Sargent] kept the first and last clauses or sentences of many paragraphs while deleting the 16 lines in-between. I felt cheated! Everything that got cut was great! However, upon reflection, I kept in mind that what remained was just as great.” Such an editorial synecdoche situation recalls Thomas Wolfe’s first novel, Look Homeward, Angel, which Maxwell Perkins shaped by using his business scythe on the original O Lost manuscript, itself around 1,100 pages, a novel more about the town as a whole than the one budding protagonist. These are books from writers who, as Faulkner phrased it, try “to put the whole tragic history of man’s struggle within his dilemma on the head of a pin,” attempts that are as impossible as they are majestic to behold. It took around 70 years for Wolfe’s restored vision to make itself known to readers. How long until we can have the pleasure of turning over every stone of Mossman’s ceaseless summer?

“In these stones, he thought, lie the dreams of my waking; in these dreams lie the stones of my sleep….”

Editor’s note: The aim of Invisible Books is to shine a light on wrongly neglected and forgotten books and their authors. To help bring more attention to these works of art, please share this article on social media. For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.