The Seahorse is a novel in two voices. It begins with a character’s attempted suicide by drowning and ends with his testing the sincerity of that original attempt. Leaner Red, a virologist, is responsible for a contaminated batch of vaccine that infects the public. He is already a self-appointed sin-eater obsessed, since his aggrieved childhood, with the all too manifest meaninglessness of death. From his perspective, the sin-eater at least gives causality to mortality, albeit at the expense of perpetual grieving and self-blame. His rescuer from drowning, Sestina, is a marine biologist studying the infertility of seahorses, a malady threatening to extinguish the local species. She is Leaner Red’s rescuer at sea, as well as in the struggle to overcome his morbid obsessions. On this basis she recruits him to the cause of her research. Rosa, Leaner Red’s sisterly childhood friend, the daughter of his mother’s lover, conspires with Sestina to “save” him from himself. Two small children, precociously gifted with extraordinary physical vitality, complicate the trajectory of the plot.

As the sea rose to the roof of his mouth, his salt-stung eyes and nose teetered on a wobbly horizon. He was weighted with the stones of exhaustion. What he took to be his last breath bubbled up with flippant buoyancy at eye level.

He was quite unaware that he had been sighted.

The woman appeared no less surprisingly to him than the speck of him that she had wished to rub from her irritable eye when it blew shoreward from the distant focal point of her concentration upon the horizon. Bobbing herself at that moment, with the ever more violent quaking of the dock beneath her bare feet, her toes levering her body for a better scan—just as she was preparing to turn her back on the bay to seek her own shelter from the imminent gale—she spotted him. She was tethered to his rescue even before she could make out the features of his helplessness.

She broke the surface of the water, no less than a flailing arm’s length away from Leaner Red, as if she had been dropped from thin air instead of spouting from the depth into which he had consigned himself to sink. White rimmed diving goggles peered into the abyss of his distress. She immediately wrapped her legs around his midriff, offering the reassurance that he could be raised to the surface. Her arms found a hand grip under his armpits. She turned him on the winch of her purposefulness, with a muscular torsion as tensile as a steel halyard. He recognized the lifeguard’s rescue hold, the tow. He had seen it diagrammed in a book once. He had unsinkable confidence in the buoyancy of the book’s instructional illustrations, menaced though they appeared to be by arrows indicating the arrangement of the limbs out of which the lifeguard must fashion the flimsy raft of salvation, should she be so well schooled.

But what had brought her to him? The unbidden rescue, it occurred to him, was like the lover’s kiss if a lover really loved…unbidden.

What had brought him to this, he mused, was oddly like the end of a kiss. With an iron crowbar, levered under its rim, he had broken the suction that held the boat’s bulky white plastic seal against rising water. Indistinguishable from the plug that drains the fill of the bath, the broken seal in the cockpit floor began to fill until he should be carried briskly off his feet. In a matter of minutes the deck of the day sailer would be a spinning vortex summoning him to the bottom.

Her face, near enough to pucker his lips was, of course, no smooch. Her business was at hand. As she turned her head, steering belligerently for the shore, he felt the blow of her skull against his nose. It was a fair rebuke to his foolishness, imagining as he did that she might have come for him as if he were not just any human speck on the horizon.

She cupped his chin in the palm of her hand, locked his head in the crook of his arm and began to kick. Leaner Red felt the dead weight of himself, the drag of his heels against the frothy wake of the lifeguard’s leggy propulsion. He felt the sudden restoration of his buoyancy as if it were the spirit departing another’s body. His eyes splashed skyward. The lifeguard’s laboring breath seemed to give animus to the spirit. Leaner Red watched a cloud wriggle lasciviously in the invisible arms of a wind that must have been blowing as high above him as the little skiff was by now certainly sunk below.

The lifeguard’s body was stiff and slick as a keel beneath him. Skimming the surface of the water gave Leaner Red the sensation of himself as a flat bottom hull. Together, rescuer and rescued were a single unit, running to shore as if under full sail, her eyes pointed in the direction of a sandy anchorage, his eyes still lost at sea, until, at last, the two views fell together. Leaner Red sensed his feet suddenly dragging against a sandy bottom, rising to meet him where his rescuer’s gradually relaxing efforts had delivered him. With a brisk counterclockwise twist of her elbow, as mechanical as a wrench head loosening its nut, the rescuer let him right himself a few yards from the shore, the better to regain his land legs from the deep. Instead he bobbed haplessly in the shallows, unable to find footing. His legs had not caught up with his torso in the turbulent wave action of the storm that was still threatening to come ashore before they might take shelter from it.

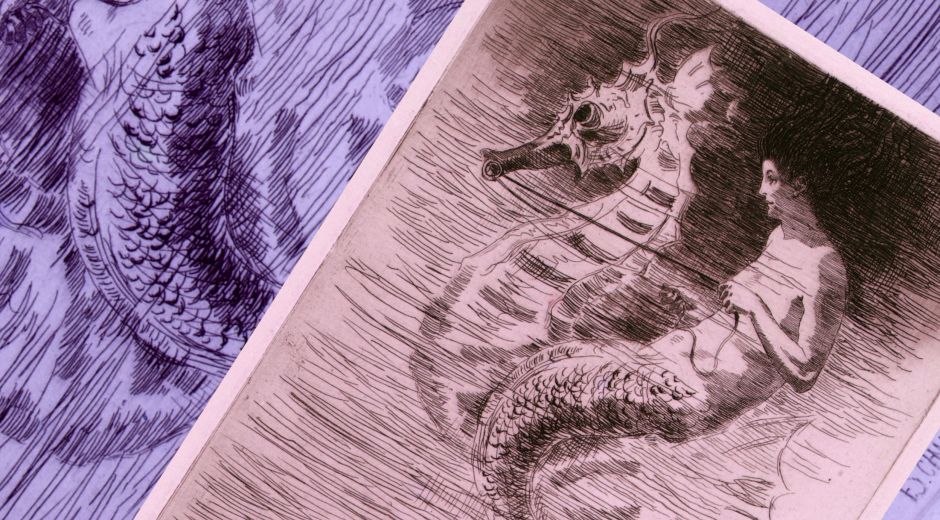

At that moment he saw himself as the seahorse he had scooped from the hoary marsh grass nibbling at the underside of the day sailer where he had unmoored it this long ago morning. Unseaworthy, this ungainly hippocampus, he had thought. So precariously riding its tail—resembling nothing so much as a rider bouncing off its mount—this bony fish might have welcomed the rescue of Leaner Red’s broad palm, reaching far over the varnished port side rail. He had scooped it up. The armor plated wriggle of the prehensile tail, itching for some anchorage to wind itself about in the shallow depth of Leaner Red’s palm, now felt altogether kindred to him as he struggled ashore.

At last, finding his feet in the sand, he lost the strength of his legs entirely. Leaner Red dropped onto a softly heaped billow of dry sand. Face down, he considered his anatomical orientation. This was his ventral side, he thought. The sensation of his belly heaving against the sand, displacing the grains enough to leave an egg-like impression, reminded him of another detail of seahorse anatomy, on the ventral side: the egg sac.

Under the meniscus of the microscope, the eggs appear indistinguishable from sesame seeds in aspic. My tongue heaves involuntarily against my front teeth as my concentration, hovering in the turreted gunmetal eyepiece, might be salivating over the granularity of focus. The seeds are bustling against one another in the salt solution that holds them in its bubble. They are unseeded eggs. But one. Only one is fertilized. Gestation displays startlingly enough as quiescence. The neat fit of cell wall to cell wall is frictionless. Their division, lubricated with such honeyed silence, glints evermore mirroring facets. A jeweler’s inspection is no more meticulous than the slow grind of my pupil across the scintillant, multiplying planes of the zygote. It is no more engrossed. Until my polishing pupil snags upon the coarse grit of a sudden arrest in the mitotic process. The morbid flaw?

In the laboratory where I am perched on a telescopic aluminum stool, the better to peer downward into the eyepiece, they have pitched the ceilings high and so given our research efforts a depth that I might even call watery, silent as it is, except for the almost subliminal hum of the technologically advanced lighting above. Yes, the laboratory is also bathed in an uncanny blue light. It emanates, we are told, from a rare filament that flatters the human eye with the illusion of real daylight. We are told that is a blue light. But this miraculously elucidating element is invisible to the naked eye. We see it as impeccable, colorless, clarity.

The sharp edges of vision honed by that light serve my science well. I can cut myself off from my colleagues on either side. I can concentrate. I can study my specimens as if I were the world of their being. I am a woman enclosed in a glass box, an unseeing exhibition of herself. I might be a wax figurine in a museum. There would be a card warning not to touch. Do not approach the glass. Everything you are meant to see is already visible.

In the elliptical eyepiece, however, the resolution of focus, calibrated by my blind fingertips, reading the grooved braille of the steel knob, so responsive to my ratcheting touch, takes me beyond what is visible to the naked eye. The zigzag lines of the suspect contaminant are so far unfathomable. They are unrecognizable where they nonetheless stand out in relief against the otherwise revelatory red and yellow dyes with which they have been stained. The Vibrio virus has been ruled out. But the sharp angled geometrics of the contaminant cells betray a resemblance to that infection, otherwise known by the appearance, to the naked eye, of snout rot. Resemblance certainly does not suffice as a diagnosis. And yet, it points our research in a followable direction. But not today.

Now I lift the tensile tips of the stage clips. I click off the microscope’s illuminator so that it is no longer peering up at me, challenging my eye-sighted vision. I remove the beveled glass slide upon which the eggs have come morbidly to rest and I file it in the steel rack, in the drawer beneath the examining table. The drawer slides shut on silent rollers. I ease myself from my stool.

I am scheduled to return to the water at this hour daily. Each of the outdoor tanks is brimming with hundreds of male hippocampi. The tanks are sheltered under a protective canopy. It casts off the opaque gleam of pearl. Otherwise it is a plastic dome, hovering high enough to simulate its own weather system of ever recycling humidity. The metal tanks are shallow. As one approaches, the surfaces seethe, as if under a sudden downpour. Each tank harbors four hundred live specimens.

The seahorse, a notoriously infelicitous swimmer, derives an unnatural sense of balance from the over-crowdedness of these enclosures. Under the apparent stress of being so sardined, the creatures enjoy the crutch of being able to lean buoyantly against one another instead of capsizing from the unsteady support of their curled tails. They are brewing their moribund eggs in the ventral sac intended by nature to mother gestation. It is not a question for me why their anatomy mimes the querulous punctuation of a question mark.

I shuck the heel-grabbing rubber slipper from my leading foot, as I lift the wand of the receiver-net dangling from a hook on the handrail, and descend on perforated aluminum steps into the tank. I delicately point my toes, the better to part the carbuncular sea of animals roiling in this corner of the tank. The nutrient-rich water conducts the warmth of infestation as much as of gestation, for which our research is specifically organized. Our research tells us that propinquity is fraternal to fertility.

Our campus of sleek, low, light-absorbing buildings, with its mature trees throwing deep shadows across grassy fields, is glossed, especially on sun-lit days, with a system of puddling tanks. They are distributed in the manner that nature feeds a network of ponds, one overflowing into another. We appear to be far from the sea. Woodland. Meadow. Mountain glen.

The sweet scent of those scenes is corroded by the sting of salt in the air and the sound of wave slapping rock, the screeching gulls, the breeze that strops its cold edge against the cheek when one steps closer to the sheer precipice which falls to a rocky shore, softened only by the emerald-furred eddies of seaweed and plankton hectically ebbing and flowing among the glossy boulders. A dingy foam collects in pockets along the shoreline. We are seaward.

In the tank I feel like I am standing on that precipice. Or I have already taken the false step that might carry me over the edge. My bare foot recoils from a sensation throbbing against my instep as if alive. Though life is teeming around me, what is directly underfoot adheres inanimately to my sole. Its slipperiness throws my balance off. In my cringing fingers it is a mash of spine and gnarled epidermis. A teasing morsel of softer flesh squeezes from its leathery envelope.

Because I am off balance, standing on one foot, the fouled one wriggling in my scraping hand, I topple. I am abruptly on my back splashing in eleven inches of water to regain my full height. Even in this shallow depth my arms flail as they would never under the most ominous cloud of a storm-bearing wave at sea. I do not wish to bring more slaughter into the tank, thick as it is with specimens whose soft bodies are as easily macerated by the human touch—not to mention the blows of a woman struggling to right herself—as by the mysterious inner malady of the dead specimen upon which I had just trodden.

The empty skin of the animal now floats as flat on the unsettled surface as algae scum but is recognizably a specimen lain dead for days on the floor of the tank, fished up by my errant foot. But I have chosen my words poorly.

It is unquestionably a fish, not an animal, though the vividly snouted anatomy brings the mammal to mind with as troubling a cerebration as does the image of a unicorn, a satyr, a mermaid. The snout is toothless. It sucks up its necessary nutrients, even its wriggling prey, from the sand encrusted crannies that abound in the airless shallows and submits them to a process of disintegration. Larger prey is accommodated by a bellying expansion of the snout that uncannily mimics the ventral sac wherein the female has deposited her fifty or fifteen hundred eggs to be fertilized. Reversed pregnancy, we say. It is as confusing as a mirror image, as the logical reversal conjured by the image of a horse galloping in the depths of the sea.

My creatures are dying of infertility. Paradox on paradox. How many earthly species remand the gestation of fertilized eggs to the male? The alligator pipe fish. The South American marsupial frog. So little faith has Nature in the bountifulness of the male. Nonetheless, the seahorse is the most prodigious of all, if bounty is the measure. All the more perversion in the fact that the eggs of these specimens are putrefying in the incubating pouches that mother nature has provided. She is an avid experimenter as well.

As I gain solid footing again, salinated tank water dripping tearfully from my chin, my elbows, the seat of my pants, I am a surveyor. I have not lost my grip on the receiver net which—its aluminum wand bending against the pressure of my knuckle—is still laden with my original purpose. I am scanning for the most moribund specimen among the merely sickening ones, ready to dip and scoop. I am foraging for the open maw of my microscope like a maternal bird, a magpie bent on robbing the nest. The eggs harvested from the netted specimen will be tomorrow’s nourishment for the lab. Is it not a wonder that the magpie is the only non-mammalian that can recognize itself in the mirror? In black and white. Unambiguous.

What would the seahorse see?

Before his rescue, if he could bear to admit this was how he would have to characterize it from now on, Leaner Red’s hand was a remarkably steady instrument. It was a requirement of the lab protocols he administered. The inflexible stainless steel insemination syringe necessitated mechanical precision at the needle’s point of insertion into the brittle calcium carbonate shell of the egg.

The egg, stood on its narrow end in the plastic rack, gave expanse at the other end for the laboratory technician to mark a spot. The pencil hatching is etched just above an air pocket through which the needle must pass in order to puncture a second membrane within the white carapace. Stood this way in its container, the egg’s yolk is perfectly centered in the aluminous tide it rides upon. The technician’s thumb on the plunger is the inseminating touch.

This Leaner Red knew vocationally. The technician sows a few grains of CVV. Within a week they will have replicated a thousandfold, to be drawn off from the crenellated crown of the egg by another syringe, this time as a semen-colored ooze incubating the otherwise invisible germ of the vaccine. Seed and egg. In such intimate quarters they cannot be told one from the other.

Candidate Vaccine Virus. Leaner Red’s charge was quality assessment: impurity testing—voiding bacterial contaminants; exclusivity testing—testing only the virus intended; TDPA testing—ensure that the polybasic cleavage site has been excised; embryo lethality testing—live pathogen will not kill the embryo. The genetic engineering of the pathogen works in reverse, the lethal wild virus is tamed by a chemical mirroring. The pathogen’s image captured in the antigen. It permits the researcher to scratch the nucleic tain so that the hemagglutinin gene goes vampiric in that mirror. When the researcher peeks again, the volte-face of the beneficently modified gene smiles back. Ready for vaccination.

Mirrors were his nemesis. Leaner Red was daily admonished by the sight of his face, intrusive as an unwelcome neighbor, shining forth from the ubiquitous polished chrome surfaces, flat, curved, sharply angled, that clad the laboratory work space. His encounters with himself in the surrounding gleam of things caused him to flinch. His teeth appeared menacingly large, chomping against the puffy dough of his lips. His cheeks flapped as loosely as oversized ears. His ears appeared to have been shaved from his head, as he turned violently from side to side, struggling to catch sight of one or the other side of himself. His jeweled eyes scintillating in every direction, might have been flung from an irate hand. Perhaps the very hand that he reflexively clapped to his face in order to avoid the sight.

Leaner Red had always been agonizingly self-conscious. He had borne the chagrin like a clingy veil over his head, trusting no one could see in, struggling himself to see through the gauzy texture of his reticence. He thought it might be preferable to carry his head in a loosely woven canvas bag, plunging a panicky hand into its tangled recesses only when commanded by the authorities to produce evidence of himself, his identification papers.

Leaner was a girl’s name. The mockery he endured while being bullied across the painted white lines that ruled the playground macadam of his childhood proved the point. In flight from the boys he searched the girls’ faces for some consoling sign of misrecognition.

“Soft…” his mother had confided the etymology of the name to him, “…meaning strong. Slender…meaning athletic.” So she confounded him.

Gaunt, the dictionary delivered up to his fervid page-turning fingertips on the recto, meeting incline on the verso.

“This name has no cultural significance, not commonly found in mythology or literature. No specific location in history.” The Book of Baby Names disquieted him further, bringing a blush of redness to his face that required no etymological investigation.

To which conundrum would he answer for the rest of his life?

But Leaner Red answered to no one when he was fully suited in the labors of the laboratory. He donned the starched white coat—his name sewed in a flowery script above the insignia of the lab—as one dons a mask. Under the cover of the mask he was precision itself, confidently orchestrating the exacting technical protocols for producing a CVV. The chemical profile of the vaccine must be as identical to the infectious bird virus as it could be without succumbing to fatal identity. A fraternal twin, he would say. A Cain to enable immunity. He had his sense of humor, he flattered himself, however dubious the laughter he choked back.

The strangulating hand that squelched his laughter finally, was not his own. The news of the CDC alert came to him on the radio. The word contamination caught in his ear like the buzz of a mosquito threatening to bite. Hundreds sickened. He knew this before he understood that the malady was smeared across his own hands. The name of the laboratory stung belatedly. He looked down to where it was stitched upon his white breast, disbelieving its annunciation on the airwave to which he was so habitually tuned for news of the world. He reached for the volume adjustment knob and turned until the sound was deafening. He already knew the symptoms that would be broadcast as a warning to the radio audience. The rash would spread uncontrollably. Headache. Disorientation. Bloody eyes. Vomiting. Collapse. He felt what could only be a teardrop blister in the corner of one eye. Leaner Red sopped the tear with a tissue ready to hand for clearing any microscope slide of an unwanted fingerprint.

He felt the throb of footsteps on the other side of the door, then the sound of tentative knuckles rapping upon the words QUALITY CONTROL that were etched upon the screen of pebbled glass, trembling with the force that could just as easily shatter it. Leaner Red wished to take the embraces of his commiserating colleagues as blows. They proffered their solemn approaches, one by one, outstretching arms of comfort, ample as fruit baskets at a funeral. Instead of graciously receiving the gifts more suited to the absent mourners, Leaner held his arms straight at his sides, lifted his shoulders into the proffered hoops of comfort, all the better to make contact with the hard breastbone than with the cushioning lips. Leaner Red knew it was family feeling that his mournful colleagues meant for him to warm to. He knew better that there were mournful families already in waiting for him who did not seek his embrace. Leaner Red’s glossy eyes filled with images of symptomatic bodies, not the brimming salt waters of self-pity which his four colleagues sought to rescue him from.

Burning rash. Congested breathing. Red tongue. Whiteness around the eyes heralding loss of sensation and the onset of encephalopathy. These manikins of pathogenic disorder appeared before him as palpably as the hands that patted his shoulder and condescendingly pressured him to sit. Leaner Red resisted the seat of the chair into which the four colleagues wished to submerge him. He understood their purpose. They wished to contain the spores of hysteria they suspected were already bristling on the surface of his consciousness. Of the four colleagues, only the woman, Rosa of the scolding eye, kept her hands to herself. They were tucked tightly into the pits of her folded arms.

When he broke free of the men attempting to force him into some kind of fraternal huddle, he saw at once that they were acting at Rosa’s direction. The arms folded over her chest were logs on the grate of a smoldering fire. She stood apart from the commotion, permitting more air to fan the flame of her purpose. The redness in her eyes was devoid of moisture. Her otherwise tightly ringleted hair, no doubt wrenched by the fistful into a tight bun on the top of her head, grew iridescent against the glow of the high-powered bulb socketed into the ceiling above her. When it was apparent that Leaner Red would not sit, having shaken off the shepherding hands of his male colleagues, Rosa stepped intrusively into his physical space, casually inconsiderate of his bid for some emotional privacy. She pushed that swinging door back into his face. She stood before him, arms still folded, taking deep breaths from her laboring bosom. That breath heaved words like stones across his path of escape.

“I speak for us all—you must believe me—even if it renders you speechless.”

Rosa was the one to whom voice had been given by the directors of the company: a tinny megaphone meant exclusively for his ears, since the directors knew he would be responsive to no other.

“We mustn’t. You especially mustn’t. Whatever you think, you mustn’t.”

The two men, whom he knew mostly by the haggard thinness of the one and the roseate corpulence of the other, remained opaque physical specimens like those which floated in cloudy solutions atop the highest shelves of the laboratory’s storage rooms.

“They know you, Leaner. They know you are prone to confessional outbursts. None of us want to feel the spittle of that self-righteous vehemence on our faces, as close as we will be standing to one another, braving the storm of scandal that is coming for us. None of us wish for things to worsen. None of us wish for plague. Don’t scratch the rash. The company directors have ordered me to order you to say nothing into a microphone, to say nothing that might be carried by the air even, to say nothing even silently to yourself that you will be unable to resist prying from your gritted teeth.”

Rosa stood impassably in his way. Blockage and passage. He understood how they were the same thing. Like pathogen and antigen. And wasn’t Rosa such an amalgam? The motherly smile smeared by overly wide cheekbones. The face so wide one could hardly imagine her able to turn from side to side. The spindle neck wavering like a stick under a spinning plate. A hearty bosom, a pinched waist, slim, shapely legs fitted awkwardly into the wrong sized feet, so splayed they gave the impression that they might be webbed and belong to a lazily paddling duck. Where did she buy her shoes, he wondered?

Since they were children Rosa was anxiously protective of his penchant for blurting, convulsively confessing to crimes he imagined he might expiate. Not a guilty conscience. A compulsive self-scrutiny which he had grown up with, as with an older brother not quite right in the head, for whom one must look out, be on the lookout lest he should plummet from the window he was leaning out of, catch his fingers in the slamming doorjamb, lest he should stumble into the street in front of a hurtling engine of destruction. Leaner Red recalled the first time when the inexplicable sense of bereavement fell over him like a shadow overtaking its body, shedding a darkness in which he would never be able to take a confident step forward again.

With exaggerated stomps he was denting the packed but saturated ebb tide sand of the shoreline where he strayed in the idleness of those late afternoons of early adolescence. He was carrying a stick as long as a fishing pole over his shoulder when he spied ahead of him the grey, slickly humped form of what he imagined to be a bigger fish than he had ever seen beached upon this strand. Perhaps the smallest whale. The lengthening rays of light at that time of day tantalizingly animated the lifeless form as he approached. He anticipated the salted ammoniac stench, pinched his eyes against the harsh scintillations of the drying scales, or the blazing glint of a silver lure caught in an open gill and streaming the frayed end of an invisible nylon cord. Instead, a gust of shore breeze abruptly came up to reveal a straggly tuft of white fur, appearing to lick itself, the tell-tale of a dog’s carcass.

Its one fish eye was glassily open to the child’s gaze, ricocheting a reflection of himself, as he lowered his squinting face for further inspection. The bristly, snouted head was canted upon a florid pillow of emerald kelp. The black and white piebald rough coat of the small terrier was slicked as though he were still swimming against the tide. The brown button ears were washed back upon the head, the legs and paws still articulating the futile paddle stroke that was the instinctive motor of his final exhaustion. There were no wounds, nothing that wouldn’t invite a cuddle. He trailed his fingers through the fur at the nape of the neck where the wind had fluffed it.

The most disconcerting thing of all was the appearance of nothing he might recognize as the hand of death. This pricked the child’s mind no less than a far off bark—inaudible to human sense—might have pricked the ears of the unfortunate pup at his feet. Leaner Red was delicately fingering one of the ears with his salty index finger, resuscitating the velvety texture that every petting human is alive to. And of course he stooped closer to feel the hard certainty of the perfectly segmented spine under the palm of his hand. He could not resist outlining the dew claws, shapely as berries ready for picking. The bobbed tail was still sprung with the tautness of the enthusiastic wag for his far away master. The dog was perfect.

Then how could its deadness not be the fault of himself?

The salted breeze luffing in the loose material of Leaner Red’s T-shirt prodded the question. The air bestowed nothing but clarity upon the child’s helpless inspection of the dog’s body. He studied the situation. The stick with which he might have struck at the animal’s vulnerable croup he had relinquished several sandy yards away from the scene of this encounter. His hands were not smeared with the drainage of lifeblood. He understood only what he now cradled, sopping in his own arms, soaking his lap, suddenly redolent of an underground lair, to be the result of something, something which he craved knowledge of in order to exonerate his wondering. What would the world be if no one knew how it came about that things were dead? If he could eliminate the obvious causes, even the idea of himself as an abuser of animals, all that was left was certain knowledge of himself as an innocent confessor. His confession might at least erase the question mark that otherwise hung like a door knocker in his brain.

This was what Rosa knew of him—what Leaner Red’s own mother had feared would be his worldly destruction—that he would always confess. His lips would flutter as naturally as the wings of a canary taking flight from his tongue. It was, Rosa diagnosed, something like the compulsion to free all of the birds from their musical cages, but a malady nonetheless. He would require guardianship if he was not to become an all too willing goat to unscrupulous herders.

The directors of the company knew as well how dangerous a confessional voice might be in the silent chamber of such culpability as they contemplated. They had heaved upon Rosa the burden of squelching Leaner Red’s confession—that the likely cause of the contamination was a lax protocol, a willingness of the company to expose its patients to microbial risks, small as they are and invisible to the naked eye. Microscopic enlargement alone would reveal the winking apertures in the cell wall, no less ravenous than the peeping mouths of chicks in the nest blinking for blind nourishment. Whose expertise could deny that these windows might have been beneficently shut by the scrupulous application of a low energy electrical current? This precaution had been suspended by the directors of the company until further notice. Leaner Red had noticed. To notice is not necessarily to know. But Leaner Red knew, with just as much conviction as he had known the dog to be his.

I had spied him, shifting his weight from one foot to the other, at the galley way to the dock. I did not immediately recognize him as the drowner, the aspiring suicide whom I had impatiently studied on the horizon, scuttling his sailboat under the rushing shadow of an oncoming squall. From my vantage point, now at the dock’s furthest reach into deepening waters, I could make out his distress. But with the wind in my eye like a droplet of blown rain, my gaze was nonetheless fogging his face.

It is the fate-dilated eye of the drowning victim that imprints itself most indelibly on your memory at the moment when he realizes that rescue is at hand. Your hand specifically. But the rest of the victim’s face is a blur. Within an arm’s length of the victim’s hysteria you are immediately focused on pectoral flesh. The chest is the fulcrum of flotation without which rescue would be impossible. If it is pulsing with adrenaline all the better to give hard purchase for the tow. You clap an arm athwart of that firm bosom. You secure a hand under the armpit. You toss your head towards the shore and pull. If you are kicking vigorously enough, the body will buoy to the surface like a skiing sled.

You are effectively a barge.

And then again, once brought to shore, any distinguishing features of the victim’s face are sunken from view beneath the bubbling gratitudes of the hopeful mourners who watched from a cresting dune. The admiring witnesses descend on one. The ever more effervescent encomiums to the rescuer are proffered as distractingly as flutes of champagne. We lose the details of the face we’ve saved in the wash of praise for our so-called heroism. It is as complete an erasure as the waves perform, no sooner than the rescued body has been dragged from its sandy intaglio by the ambulance crew.

At a distance we would never be able to recognize the totality of the face again. But the victim’s eye, the frayed iris awash in its own coral-reefed sea, that resembles nothing so much as a floating island, will always be a locatable destination for the rescuer because we know what it means to be seen by someone who can see nothing but ourselves. I knew Leaner Red from the look in his eye. But why?

Why was this noticeably agitated figure, the blunt shiny black spikes of his hair giving the appearance that he had arrived on the incoming tide still sloshing against the pier posts beneath our feet and who exhibited a listing gait that belied the rock solidity of the steel planking he trod upon, why was he looking for me? I could see that he had recognized my face. He navigated his way through the other faces floating past him on the crowded pier like a diver shivering a school of fish with determined goggle-eyed invasiveness. The dock was bustling with fishermen, fire inspectors, bait hustlers, cawing knots of school children out-screeching the gulls, boat mechanics, and women.

Neither was I alone at the spit end of the pier. We were five women in a huddle, all nylon-suited in the same colors, orange and black. The team of women rescuers to whom I belonged—I do not say to which I belonged—were pledged to the fatalism that the sea holds in its most deeply sunken depths. The certainty of drowning.

The relentlessly approaching figure appeared no less certain of his mission. His stride was ominously unbroken by any screen of formality. I have seen people stumble through screen doors under the same delusion of a clear path.

“My name is Sestina.” I would have to introduce myself. We were, after a fashion, meeting for the first time.

But when he reached out to me it was a full-bodied embrace, an eerily orchestrated reprise of the exhausted swimmer clawing after the flotsam of his own wreckage. It bobs as perilously on the flimsy surface of things as the splashing hand itself when its reach falls short of the approaching rescuer.

But he already had me in his arms. My hands, fluent in the language of the recalcitrant body panicking even against its rescue from unfathomable depths, reflexively locked in the small of his back where I could feel the increasing vulnerability of the smaller and smaller bones of the spinal column, the lumbar finger joints, susceptible to the knuckle pressure of my grip. Joint to joint, I held the advantage. And where was his face for me to judge how to press that advantage? It was snuggled in the crevice between my neck and shoulder, the eyes that had glanced my bridling gaze at his unstoppable advance, the artlessly unshaven jawline, a jagged scar pulling at the corner of his mouth like a hook, a winking tooth, the shuddering chin, now all running to tears down his ruddy cheeks.

When I lifted my gaze from the rippling emotion of Leaner Red’s embrace, the blood surely rose in my face. Despite the anonymous commotion at this business end of the dock, I realized the otherwise busily distracted faces were all turned my way, illuminated with the mistaken impression that they were smiling witnesses to the reunion of two long separated lovers. Leaner Red’s heaving shoulders, smothering his sobs, must have appeared as nothing less than long pent up passion, and yes, some titillating intimation of the private physical act toward which the public embrace was hurtling.

And what of my red-faced comrades oblivious of their violent clash with the slashing orange sheen of their one-piece nylon suits, the black half notwithstanding?

Well, I am a rescuer among a team of rescuers. A pod. We refer to ourselves by that nomenclature, the easier it therefore is for us to hold faith with the idea of an organic, a natural bond between us, beyond the circumstantial warrants for our confederacy. The orca pods are led by females no less. We are five who, each in her own dripping scene of emergency, have wrestled with a flailing body under the slipperiest conditions. Lovemaking is just such a rescue isn’t it? So I understood how my gawkers could be forgiven their voyeurism, however blinded by misapprehension. But this still left me with the decision whether to tender Leaner Red the same generosity. Or to strike him a blow to the face. Or deeper. I possess my greatest strength in the bone-bristling flexure of my knees. And yet his clutching arms left almost no breathable space for unlimbering a combative limb, giving it torque sufficient to fling Leaner Red onto his back, heels over head onto the steel planking of the pier.

What were my comrade gawkers’ eyes making of it? How would I know since I was such an integral part of the spectacle?

A fully grown man sobbing in my arms. The sound, drowned out as it was by the screeching, clanking, hoarse-hawking, bustle around us, was sensible to me only as a spasmodic puckering of his lips against my neck, bringing to mind the motions of a fish mouth seeming to blow the belly of the fishbowl rounder. How do I not find a drop of compassion to drip into that bowl? I let the muscle in my arms reciprocate the pulsing breath from his lungs in an oblique simulation of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

The picture was complete: a startlingly fit young woman streaked with orange and black spandex delicately crimping the flesh under the arms and where the legs joined the torso, the exposed flesh shimmering with the delicacy of rose petals in sunlight—though just as delicately roped with muscle—sinking into the deepening embrace of a pink-hued young man, fully cloaked in black wool and clinging denim, weighted down with leaden grey rubber boots, his back bent to the labor of proving he was back from the sea for good. An image for swooning hearts. The maudlin conclusion of a well-worn yarn of the sea.

How easy it has been to live with him.

We are coupled by a passion for rescue. We are, hand in hand, sensitives of the pull, that is the need of another hand. It is felt most urgently in the burning palm, curling around a ghostly thread of hope, through which the braided rope end has already slipped. The man overboard. Leaner Red and I know the man overboard as well as we know ourselves.

Listen to a conversation between Alan Singer and George Salis on The Collidescope Podcast:

Alan Singer is the author of seven novels, including The Charnel Imp, The Inquisitor’s Tongue, and Play, A Novel (Grand Iota, 2020). He also writes about aesthetics and the visual arts. His most recent work in this area is Attending to the Literary: the Distinctiveness of Literature (Routledge, 2024).