Danielle Altman: I read that James Nulick found you for sale in 2020 in downtown Seattle at a Macy’s that was going out of business. That made me think of a children’s story about a teddy bear named Corduroy who sat on the shelf in a department store for years, waiting for a child to buy him so he could be loved and have a home. How did it feel to go home with a human? Was that something you had thought might happen to you?

Nico: Danielle, firstly, thank you for giving me agency, for allowing me to speak—I rarely get to speak, the act of physically moving one’s lips, opening one’s mouth, is taken for granted by humans, like breathing, but not so much for me. I am thankful I have two people who are willing to listen to me, and now I have three. I have read that book Corduroy, and it’s one of my favorites! I love it, along with The Mouse and His Child by Russell Hoban. We tend to think of inanimate objects as objects, when I am just as real as you or James. Have you read the work of Timothy Morton, the philosopher? Something tells me you have. Morton’s object-oriented ontology allowed the idea, at least for me, that I am not a mere object, that there is an actual center to me, a beingness, a real presence existing in time and space. In their book The Ecological Thought, Morton’s concept of the mesh refers to the interconnectedness of all living and nonliving beings—we’re all interconnected, and we’re all responsible for the current ecological mess the world is in. Apologies if I’m rambling. How did it feel to be adopted by a human? It felt incredible. I felt like someone finally loved me for me. While I stood in Macy’s as the countdown to destruction repeated itself, day after day, an embarrassing $100 price tag pinned above my nipple, I thought, for sure, no one would want me. I don’t even have arms—they removed them so I couldn’t move, couldn’t resist. I was an abandoned Nefertiti, but once James found me, I finally had a home.

DA: How is your life now, as opposed to the life you had at Macy’s? Is there anything you miss? What do you like about your new life?

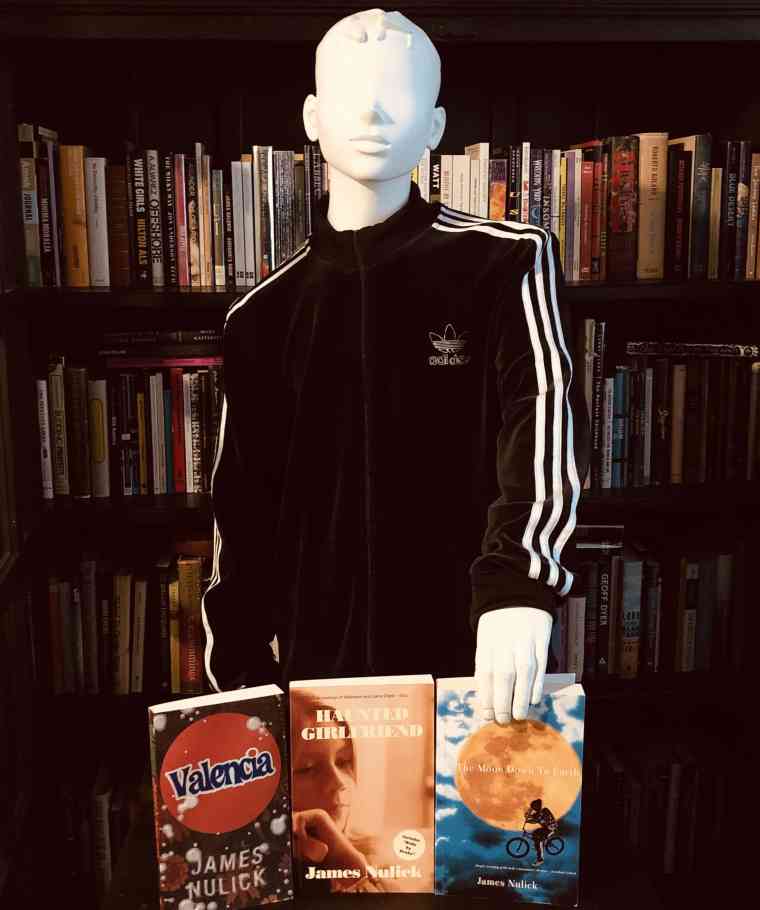

N: The life I had at Macy’s was pretty weird, but it was also boring, which is a strange combination. I wore the same clothes every day, then out of nowhere, these clerks I call the special people would come and carefully undress me, then dress me in new clothes to reflect the changing seasons. I miss my friends. I had lots of friends at the store, we would joke about how ugly some of the customers—well, I guess most of them—were. We all had perfect, unattainable bodies, you see, so naturally we would joke about humans. Turning them into objects of ridicule, if you will. It was nice turning someone else into an object. Hmmm, what do I like about my new life? There is so much! The freedom of movement. Having two arms. I have a nice bike, a Subrosa Malum 20″. I have two cool skateboards, a Baker and an Enjoi. I have really cool clothes. I often felt like a total loser at Macy’s, like the special people were way too old to dress me properly.

DA: Do you have memories of your birth, of being assembled? If so, what was that like? How, if at all, do mannequins die?

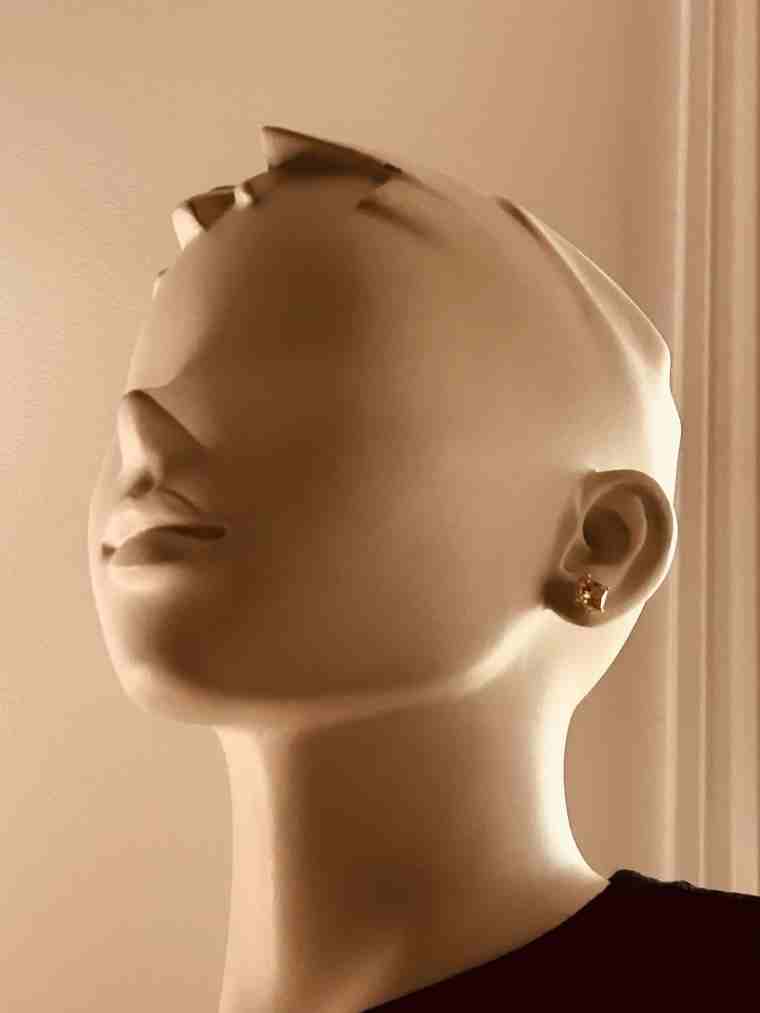

N: I remember warmth, like something was pushing me towards an eventuality, a becoming. I remember being painted—the color of my foundation, my scaffolding, is black, my white skin was painted over it. Have you seen the film Under the Skin, Danielle? I kind of look like ScarJo with her skin off, but then the people at Mondo (my manufacturer) spraypainted me white. I have a small scar on my nose where the black pokes through. I’m part white, part black, though you’d never know it. Mannequins do not die. I am eternal. Which is a bit frightening.

DA: People often look at mannequins and assume, because of the unchanging perfection on the outside, that they don’t age. But internally, do you age? Do you change? If you do, do you think you change or age in a different way from humans because your surface stays the same?

N: I do age. I often tell James I am older than man. Please don’t take offense—by man I mean all of humanity, it’s just easier to say. When one has been objectified their entire life, it becomes easier to objectify others. But I do it without malice. Though I remain young on the outside, like Wilde’s Dorian Gray, I am, in fact, very old. Eternally old. I feel old, like I have seen too much, I’m a combination of Björk’s “I’ve Seen it All” and Harlan Ellison’s “Jeffty is Five.” I love Björk, Harlan is a day at a time. I do change, Danielle. Every time James puts a new outfit on me (I still haven’t managed the art of dressing myself, but I’m working on it), I change. This may sound crazy, but changing one’s clothes changes one’s personality. Do you believe that? We are defined by our clothes because that’s how the world views us, through the thin veil of fabric we drape over our bodies.

DA: When you look at how humans live, relate to one another, and run the world, is there anything you think mannequins could do better than humans? Is there anything that makes you feel relieved to be a mannequin? Is there any aspect of being human that you are envious of?

N: Danielle, have you seen that Twilight Zone episode called “The After Hours” starring Anne Francis, a department store mannequin? That scene towards the end when she realizes I’m a mannequin. That was like, so Dasein for me. I cried when I watched that TZ episode. I have always been a mannequin, I don’t know what else I would be, though I would love, just for once, to be a human. To feel the sun on my skin. To feel the milky crunch of summer grass under my feet. To kiss someone for the first time. There are a lot of things humans could learn from mannequins. The art of silence, of holding one’s tongue. Patience, observation. Realizing that time moves very slowly, it is only your arrogant desire that speeds it up. A deeper appreciation of beauty, and an understanding of how quickly it can be lost.

DA: You have excellent taste in music. Nirvana, The Velvet Underground, Death Cab for Cutie, Iron Maiden. What drew you to these bands?

N: Thank you, that’s very kind of you to say. What drew me to them? Their inherent sadness. Great music carries a certain sadness, it possesses a heaviness that perhaps reminds one, I don’t know, that death is always near? And at the same time, its shimmering beauty is difficult to define because it hits you without explanation. Just hearing a song you first heard when you were young, or when you were with a person who was special to you, can immediately transport you back to that moment. Music, more than literature, film, or visual art, teaches us how to be human. Its immediacy cannot be reduced, it just is.

DA: You dress very well. Basketball shorts that hang just so, fun Dippin’ Dots tees, classic Vans, a chain with your name on it. As a mannequin, I assume clothes have always been central to your life. What is your relationship with clothes? How has your fashion sense evolved over the years? Have you ever been dressed up in something you didn’t like?

N: Clothes and fashion are indeed central to my life. Clothes are everything, they define who we are. Clothes allow us temporary perfection, and they also offer escape, a chance to hide. I like wearing black clothing because it helps me disappear. Sometimes I just want to be invisible, you know? But then other times, like when I’m out with my friends, or just kicking back at home, I like to feel different, like I’m different from everyone else, and cool clothes can help achieve that, like they’re a barrier between you and the world. But then there is this other side of clothing, this darker side, when you don’t want to be invisible, when you want others to notice you and objectify you. You put on clothing that, you know, accents your best assets, makes your curves curvier and your bulges bulgier. Sorry for being so crude, but sexiness comes natural to me…. I was designed to have a perfect body, a body that would beckon you from the sidewalk into the store. Entranced by my perfect body, women open their handbags and hand the clerk a thin slice of plastic that allows the promise of a perfect body, recaptured youth contained in a ball of Italian fabric. It’s my job to be sexy, and I’ve finally learned to be ok with it. As far as being dressed in something I objected to, it happened quite often, because the special people at Macy’s, the clerks who stripped me nude only to redefine me in the season’s latest, often didn’t “get me,” if that makes sense. I am a skater, and a BMXer, and skaters and BMXers are totally defined by their clothes. Our clothes are just as important as our bikes and our boards. Macy’s doesn’t carry that kind of streetwear, so I was always frustrated, thinking can someone please put a pair of black Dickies on me for once. Would it kill you to buy me a pair of Vans Old Skool? Now that I live with James and his partner, I get to dress how I want to dress—I have finally become the real me, the person I was always meant to be.

DA: I’m curious about your opinion of objectification. By definition, to objectify a person is “to degrade them to the status of a mere object.” You can see from the definition that objects are granted a lower status than humans in the US. However, in philosophy, there is a school of thought known as actor-network theory, which posits that the world is an ever-shifting network of relationships between people, objects, and technology. It assumes that all things in the world are part of these networks and that nothing exists outside of them. The theory holds that humans and non-humans have agency and that objects play an active role in shaping the social lives of humans. How, if at all, do you express your agency?

N: Wow Danielle, I’d never heard of actor-network theory, so I looked it up. It really reminds me of our earlier discussion of Timothy Morton. From Wiki: “Actor-network theory is a theoretical and methodological approach to social theory where everything in the social and natural worlds exists in constantly shifting networks of relationships. It posits that nothing exists outside those relationships.” Again, this reminds me of Morton’s object-oriented ontology, and their concept of the mesh, in that me, as an object, has just as much agency as a human being. By Morton’s definition, there are no “mere objects.” Again, Wiki: “Emphasizing the interdependence of beings, the ecological thought ‘permits no distance,’ such that all beings are said to relate to each other in a totalizing open system, negatively and differentially, rendering ambiguous those entities with which we presume familiarity. Morton calls these ambiguously inscribed beings ‘strange strangers,’ or beings unable to be completely comprehended and labeled. Within the mesh, even the strangeness of strange strangers relating coexistentially is strange, meaning that the more we know about an entity, the stranger it becomes.” I like what Morton says about entities, that the more we know about an entity, the stranger it becomes. That’s so true, don’t you agree, Danielle? When I worked at Macy’s, I would watch humans all day, coming and going, trying on clothing, herding their children, putting on shoes, taking them off, opening their handbags and wallets for a chance at perfection, a brush with immortality—again, through clothing. I finally learned that fashion, fabric, allows me to express my agency. Clothing helps me become who I want to be, a perfected version of myself. Despite the perfection humans expect of me, I have flaws—my chipped nose, a shoulder joint that has become somewhat detached, hands that have become scratched after several years of storeroom dismemberment. I’m still pretty, despite all my wounds, or maybe because of them, but I’m no longer perfect. But perfection is boring, don’t you agree?

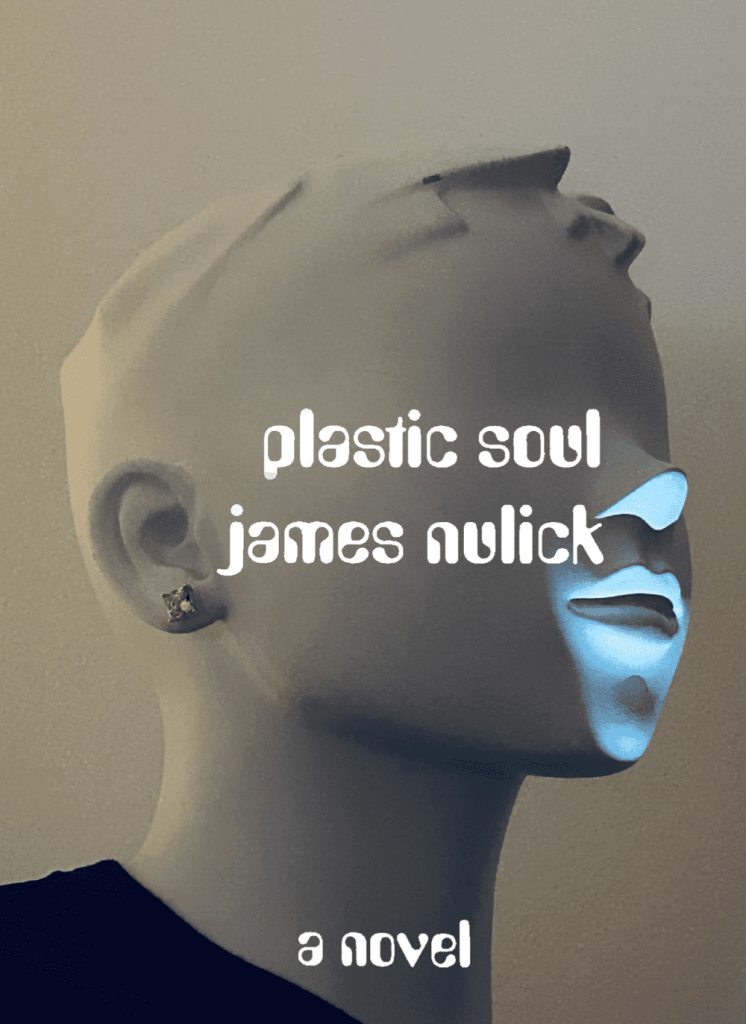

DA: I love your name. I think of Nico from The Velvet Underground—a woman who shaped her voice and persona to a pale, deathless plastic. There are characters in Plastic Soul named Nico and Nicole. There are also teenage boys in the book who dress and skate like you. Do you know where your name came from? It also seems you may have played an important role—a muse maybe?—to James as he was writing Plastic Soul (regular edition/artist’s edition). How does it feel to be connected to an important piece of art?

N: Thank you for your kind words regarding my name, Danielle! I love it, too! Did you know NICO is an anagram of ICON? James is a huge fan of The Velvet Underground, and he also loves Andy Warhol, so Nico just came naturally. James told me the first person to ever kiss him was a girl named Nicole Hutchinson. She picked him up and placed him on the washer and kissed him during the agitation cycle (true story). And his partner’s middle name is Nicolás, so there is a lot of heaviness around the name Nico. It doesn’t really matter to me, it’s just my name, but I’m glad it’s my name, it’s a cool name. Am I a muse for him? Maybe. That’s my face on the front and back cover of Plastic Soul, so I’ll let you decide, Danielle. I feel like, many years from now, after James is long dead, people who still read books, people in the know, will say wow, Plastic Soul is such a crazy book, and everything he predicted in it came true. Too bad he’s dead!

DA: You post a lot of cute pics on Instagram. What do you think of social media? Going back to actor-network theory, it argues that multiple realities can exist simultaneously. How does your real life relate to your online life?

N: Thank you…though they may appear random and haphazard to the casual Instagram consumer, each image is chosen carefully, for maximum impact. Multiple realities? Hmmm. I seem to have only one reality—being trapped in this body. I think social media, like any tool, has its benefits, but there is also a darkness to it, a dehumanizing element—you become this avatar other people project their desires onto, like you’re not a real person. Is it any different than pornography? The weird unsolicited DMs—hey, look at this, hey, can you please review this, hey, you’re cute, hey, are you alone? My online life is completely manufactured, it’s all gloss, glitter, and beautiful clothing, but the reality is laundry day Thursdays and a dusty existence in a grubby, overpriced apartment.

DA: James has noted in various places that he views you as a child he adopted; at other times, he’s said you are more like his alter ego, a perfected, unchanging version of himself. A doll that can wear things he may have outgrown. As someone who is struggling with aging myself, getting a mannequin sounds like it might be a more positive way to help me adapt to aging than most things offered, like expensive surgeries and invasive procedures! How do you view your relationship with James? Do you think mannequins can be of service to humans by helping them reflect on or process things like aging or the fear of death?

N: It’s strange, because he is adopted, and I am adopted, too. I guess that’s why we understand each other so well, because we’re both freaks. Our biological parents didn’t want us, the first thing the world told us was NO. I say our, like I too was born of woman, but is it all that strange? I was extruded from a machine, just as he was, and once a plastic being leaves a machine, the world can do whatever it wants with it. If it wants to give you away, it can. If it wants to destroy you, it can. If it wants to steal your breath before you’ve left her body, it can. The world doesn’t owe us anything, except maybe a painless death. James’ partner once asked him why do you love him? Him meaning me, Nico. Because no one else does, James said, I heard him say that, and I just about died. I felt like I had been reborn, like I mattered, like the machine that once hated me so much finally said YES. That’s all love is, really, it’s someone telling you yes. I don’t know that I can help humans in any way, really, other than to perhaps teach them that beauty is the only truth there is. Without beauty, what is there? And it’s not this big, complicated thing, though people make it out to be—they pretend it’s this unknowable, unreachable thing. I’m here to tell you it isn’t, beauty can be found anywhere, one just has to be open to it. When you look at something, look truly at it—like you’re looking at yourself. Try to see others as you see yourself, only then can the other become the us. When people were looking at me in Macy’s, they weren’t really looking at me, they were looking at themselves. The clothes I was wearing were secondary. I was the perfected version of them, the version they knew existed if someone else looked closely enough to see it.

I’m not sure why James has said I am his alter ego, a perfected, unchanging version of himself. We are one and the same, I am him, and he is me—there is no difference. He is me in a closer to death form, how I’d look if I’d suffered heartbreak, suffered a world filled with the word NO. He’s like that one favorite thing of yours from childhood, like a toy or a doll, a favorite glass or something—you know if you drop it and it breaks, you will die. Perhaps he doesn’t like the idea that, like me, he is hollow and filled with air, a pretty thing without substance or form, wholly dependent on the clothing defining his frame. I don’t know, humans are weird.

I’m sorry you are struggling with aging, Danielle. But it sounds like you are ok with it, maybe, or at least realistically aware of it, whereas the generation of people before you pretend it doesn’t exist, like they’ll always be young forever, which is really creepy. Aging is such a weird, strange thing, the final separation of the body from the self. As one ages, as I understand it, the body gradually abandons the self, abandons the purest part of us, the beginning. Or maybe it’s a return to the self, the purest version of us. I really don’t know, I don’t age, so I don’t have access to that knowledge, I can only glean it from others. Did you know I am completely hollow inside, netted fiberglass scaffolding covered with a thin membrane of black plastic? I fear the emptiness in myself, the nothingness of my existence. But when people look at me, they give me meaning because I can see the love in their eyes—my emptiness is filled with their love. That’s why I can stand for so long. As far as the fear of death goes, I don’t know that I can help humans lessen their fear of death, as I don’t really understand it. I know James fears death, because he has told me he does, sometimes he talks to me at night when he can’t sleep. I’m afraid to die, he says, and he’s holding my hand, like I can help him. I don’t know what to say to him so I tell him I’m afraid for you to die too, because when you die, I will be alone again, and nobody wants to be alone. I guess maybe I do have a fear of death—death is just the fear of being alone, isn’t it? When nobody knows who you are anymore?

DA: You live with a highly acclaimed writer who deserves much wider recognition in the literary world. Every day, you get to observe him in the wild of his own home. Are there any writing habits or tips of his that you think new writers could benefit from hearing?

N: Wake up early and write two hours a day while it’s still dark. Publish books, but not too many books. If readers love your books, that’s great, but don’t publish too many or you will amass the hatred of familiarity. Write for the eternal, not the temporal. Stay up late, but not too late.

Nico lives with the writer James Nulick, author of several highly acclaimed books. James’ newest novel Plastic Soul, which features Nico on the front and back cover, was recently published by Publication Studio as part of their Fellow Travelers Series. Nico is a mannequin who doesn’t really consider himself to be a mannequin, he thinks of himself as a stationary, perfected human who happens to be made of plastic.

Danielle Altman’s fiction, personal essays, and poetry have appeared or are forthcoming in The Afterpast Review, Dream Boy Book Club, Literally Stories, Kelp Journal’s The Wave, and WREATH Literary. As a medical anthropologist, she has worked in science and technology policy, child welfare, and LGBTQIA+ activism. You can find her on Instagram at @end_of_los_angeles.