Editor’s note: The English version of this interview was translated by George Koors (Koors translated and provided these questions to Lentz in German and subsequently translated Lentz’s answers, which were edited by George Salis). The original German text is available here.

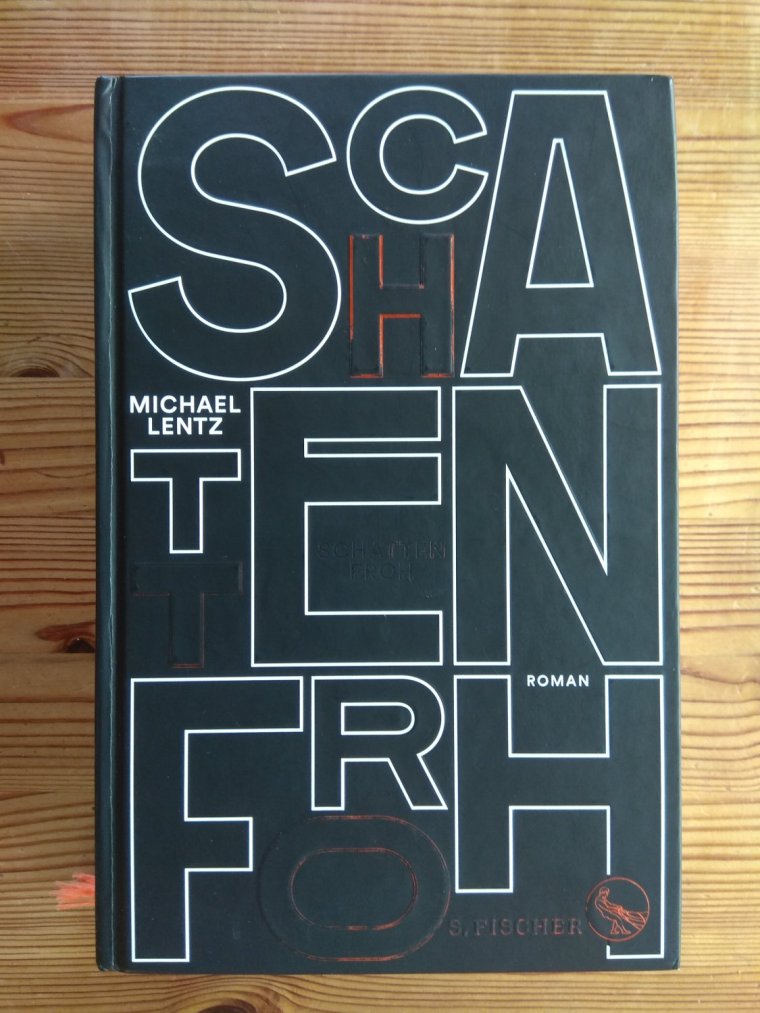

George Salis: The design of Schattenfroh is as integral to the work as the prose itself. It also seems as though the orange text on the book’s cover is designed to fade. Can you talk about the importance of a book’s physicality and how that informed your conception of the novel?

Michael Lentz: In the act, the cover of Schattenfroh is an integral component of the text; it is the text turned inside out. No one, not even the writer, always has this novel with them. As such, there should only be a single copy of Schattenfroh, and paradoxically, every reader has that single copy. Within a portion of the first edition of Schattenfroh, the orange text wore out over time. That was not planned. The publisher debated whether these copies should be recalled. I was against it; I find these copies to be more appealing than the “intact” ones: For one thing, the manuscript, or rather the book in which Neimand writes, wears out more and more over time and under the circumstances of his “journey,” and for another, toward the end of the book, Schattenfroh also dissolves, disappearing in and with his name.

The covers of my books are always very important to me. Fortunately, I have a say in the design. By the way, Schattenfroh was supposed to be exactly 1,001 pages long.

GS: I can’t think of very many German experimentalists beyond Arno Schmidt and a handful of others. Do you think German society, or society globally, puts a straitjacket on creativity?

ML: No, I don’t believe that. But it is certainly the case that the so-called market has never sung out for experimental art. Nonetheless, experimental art prevails and even sets trends. It’s a great liberation and freedom not to write according to the market’s dictates. In Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, just to name three European countries which are, at least in part, German-speaking, there have been more than a handful of experimental writers, including geniuses like Gerhard Rühm, who, with a few exceptions, have never been in the spotlight. An important exception to that is Ernst Jandl, and another is Friederike Mayröcker.

GS: How does one balance the freedom of creation with the discipline required to hone one’s craft?

ML: A very good question. Discipline is unavoidable, perhaps a requirement for such freedom. Now this setup could be: “let yourself go” or “don’t follow any rules.” Both would be a dream. Is this possible in art? I think not. In performance art, which I appreciate greatly, maybe. Even Surrealism, in the end, had its rules. Art always comes from something before it, so-called “free jazz”—Ornette Coleman rightly disliked this label—comes from bebop and the blues before it. And bebop and blues? An unending series of origins.

GS: Has Schmidt influenced your writing at all? Are there other experimentalists in Germany whom English readers need to know about?

ML: Yes, Arno Schmidt influenced my writing. For example, in his appropriation of dialects, and his skill at creating a patchwork of sentence fragments and thought fragments. Samuel Beckett influenced my work much more, however. Lately, I have been (again) reading Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf, whom I’ve become quite fascinated by.

Of the experimental writers of Germany, Carlfriedrich Claus, Helmut Heißenbüttel, Franz Mon, Oskar Pastior, and Ror Wolf are especially important to me.

GS: Nowadays, many books seem to try to exist within a void rather than celebrate the interconnectedness of literature. Schattenfroh features scanned pages from other books, references to Tristram Shandy, and much more. Can you talk about the need for reading widely and drawing attention to the fact that books come from books come from books?

ML: That’s how it is. One could assume, I am just going to write, without looking left or right, without reading anything other than one’s own emerging text. Where does that lead? Perhaps inward. Perhaps everything necessary is already in one’s head, in one’s imagination. For me, literature is about absorbing. And working through it. Exposing oneself. One should research the factual and the historical, then one can distort and change it. When I have stylistic inhibitions, I always read Thomas Mann. I know he won’t influence me, but his sentence structure stirs me up, in a positive way, just like the structure of Uwe Johnson or Gertrude Stein, all three of whom are syntactical artists. After a decent dose of Thomas Mann, I can begin again more relaxed. I can rely on his sentence structure to initiate something in me. And that is what it is about: reading as initiation. One needs to have a bit of humility, and be able to acknowledge other writers and other things.

There is nothing more embarrassing than the belief that one has invented something, that one was the first to create something. This belief is usually due to a lack of information, sheer arrogance, or poor education. Samuel Beckett and James Joyce were big readers. One needs to read all of Samuel Beckett in order to rid oneself of such educational ballast. Often, it is finely nuanced allusions in Beckett’s works, as in Malone Dies or Watt, that can give this kick. One is part of a tradition and continues to write in that tradition, one tinkers with it. Writing is also tinkering. The great Doktor Faustus by Thomas Mann is a novel assembled with an underlying education, underlying books—it’s a particularly impressive example of this, how literature comes from literature, and in this case also arises from music and music theory.

GS: The narrator of Schattenfroh is named Niemand, which translates into English as Nobody. What made you decide to anonymize the narrator? Is it a nod to Odysseus’ encounter with Polyphemus?

ML: Niemand is also on a long journey. He has an odyssey, crosses through several centuries, living sometimes in books, sometimes in reality, which unexpectedly no longer appears so real itself. The name “Niemand” was given to the first-person narrator of Schattenfroh, or at least that is what Niemand says. Who is Schattenfroh? He is father and state, devil and invention. He constantly changes his appearance, yet he never actually appears. Perhaps he is the siren song. Niemand sees it as a special ruse to adopt (and keep) the name given to him by Schattenfroh because he hopes he will no longer be identified. He is everyone and nobody. “Nobody wants to kill me with cunning or strength,” says Polyphemus to the other cyclopes who rushed to him in his cries of pain after Odysseus and his companions burnt out his eye with a flaming stake. Niemand’s cunning in Schattenfroh is different—it renders Schattenfroh harmless.

GS: Schattenfroh also features paintings, with an emphasis on Renaissance art, including the works of Hieronymus Bosch. If you could live inside a Renaissance painting, which would you choose and why?

ML: A difficult decision. I don’t want to go to hell. I would choose Bosch’s Heiliger Johannes der Evangelist auf Patmos. I would be—like the first-person narrator of Schattenfroh—the writing Johannes, and while I write, I would keep Lucifer, the black beetle with the human face, in the bottom right of the painting, away from me. I would have a beautiful view of the Rhine, which for me is the river in the painting, and its beautiful flood plains.

GS: Schattenfroh has been met with praise from readers, but there have been naysayers, such as literary critic Burkhard Müller, who called the book a waste of time. Lately, I’m beginning to believe that, aside from a handful of the right readers, a book’s purity is tainted as soon as a reader opens it up and looks at it with all their shoddy biases and anal antecedents. To what extent would you agree with this sentiment?

ML: Well, as long as it is not personally offensive, anyone is welcome to include their own preconceptions, vulnerabilities, and idiosyncrasies in their criticism. That is indeed a form of engagement. It is always interesting for me to see where a person’s limits lie. It would be terrible not to be noticed at all.

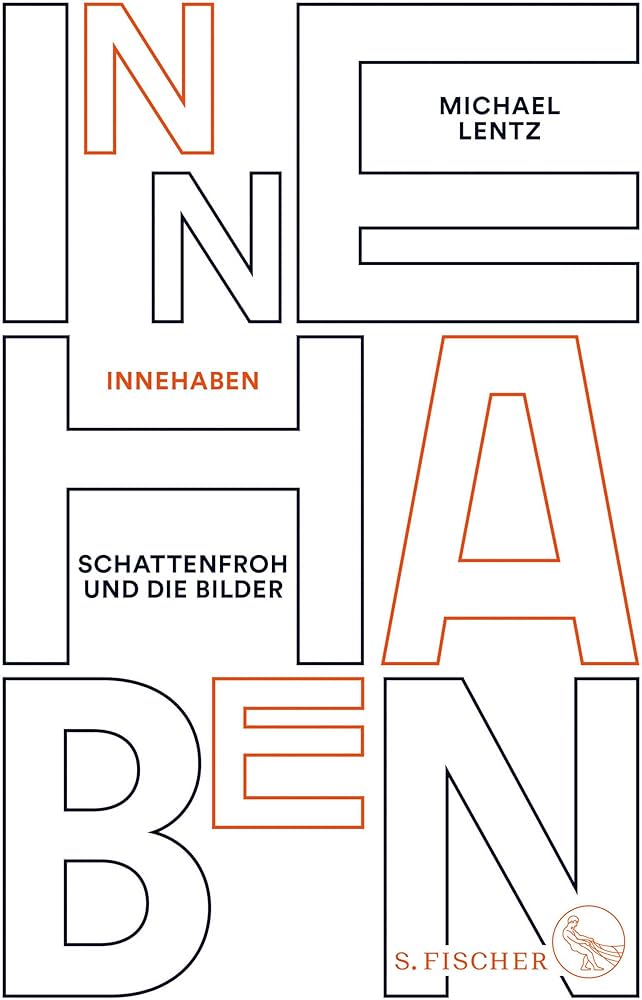

GS: You eventually came out with Innehaben, a book that explains Schattenfroh. Why did you decide to release this book, and do you think it succeeded in accomplishing what you set out to do?

ML: I obtained the Ernst Jandl Poetry Lectures and decided to write something about ekphrasis and immersion to locate myself in this centuries-old field. Schattenfroh is complex, unreadable for some. The subtitle of Innehaben, “Schattenfroh and the Images,” assumes this exact focus. Additionally, there are other aspects that I illuminate, with regard to family history and psychology. One does not need to be familiar with Innehaben in order to read Schattenfroh. For me, Innehaben is an anthology that contains aspects of the novel’s aesthetic, and it’s helpful even to me. Writing is a fleeting medium; much of it quickly disappears from memory. In this sense, Innehaben is also a workshop report.

GS: Can you talk about your work as a musician? Have there been times when your music has overlapped with your writing or vice versa?

ML: Until his death, I played in composer Josef Anton Riedl’s ensemble and have collaborated with many musicians over the years, performing in many countries. Every day, I play the saxophone for three hours. My work with the ensembles is just as important to me as writing. There is both a trio and a quartet in which I combine saxophone playing and speaking. The “speaking” is a form of speech-singing (Sprechgesang). Our music is a blend of jazz, new music, ambient, and electronic. We put out Lentz Geisse Wertmüller in 2019 and I am currently recording a new album.

GS: What is a novel you’ve read and think deserves more readers? Why?

ML: Ich by Wolfgang Hilbig [note: translated into the English as I]. I recommend it for both its use of language and the construction of the plot. The novel is set in Berlin, in the GDR; its protagonist, Cambert, gets caught in a paradoxical loop of Stasi surveillance.

GS: The upcoming translation of Schattenfroh will be your English debut. Can you tell us about some of your other works that English readers may one day have a chance to enjoy?

ML: Muttersterben will be published at the same time as Schattenfroh and perhaps at some point my novel Pazifik Exil will be translated.

GS: Aside from Schattenfroh, if you could choose one of your works to be translated into all languages, which one would you choose and why?

ML: I would choose my latest volume of poetry, Chora. It is my most complex linguistic work. A translator might “break their teeth” with this work, as they say.

GS: What have you been working on lately?

ML: Two of my books were published this year: the novel Heimwärts and the monograph Grönemeyer, about the German singer Herbert Grönemeyer, both published by S. Fischer Verlag. At the moment, I’m working on a new book of essays, which will be published in 2027, as well as poetry lectures and a new, extensive novel.vel.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as editorial services, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

Michael Lentz is an award-winning German author, musician, and performer of experimental texts and sound poetry. Schattenfroh is his first book to be translated into English. He currently lives in Munich.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

George Koors writes long-form fiction, but also composes music. He has worked as a writing professor and librarian at universities in the District of Columbia. Always the Wanderer, his first novel, came out in 2015 via Golden Antelope Press and is a fiercely unique post-modern critique of contemporary US American and European imperialism. His graphic novella, Home, was released to the public for free in 2018 and was written and illustrated by the author. In 2024, Golden Antelope Press released a new edition of Always the Wanderer. His next novel, Sing Lazarus, will appear in June 2025 via Anxiety Press. He maintains a literary YouTube channel, and you may follow him on Instagram @gbk7288, or visit his website.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.