George Salis: Gilligan’s Wake is a unique novel with a title that blends Finnegans Wake and Gilligan’s Island. What inspired you to merge these two seemingly unrelated elements, and what were some of the challenges in writing such a complex and surreal narrative?

Tom Carson: I think juxtapositions like that one come naturally to me because I spent my childhood surrounded by incongruities. I was a Foreign Service brat who grew up mostly abroad, which is a very topsy-turvy world in terms of identity and affinities. So the everyday United States whose oddities most Americans take for granted was a literally fantastic place to me. And as an outsider despite myself—there was nothing I wanted less—I got fascinated by the way our notions of “the past” are really a confused mashup of memory, history, and pop-culture misrepresentations of both. What if they’re all equally valid—psychologically, if nothing else?

That said, Gilligan’s Wake wasn’t a particularly difficult novel to write, at least once I surrendered to the ridiculous side of the idea. I had these seven characters who represented various American archetypes, something I was later told by Sherwood Schwartz’s son that he had intended all along. So much for the idea that dumb sitcoms are necessarily created by dumb people. I even knew in what sequence they’d appear, thanks to the theme song. God bless that theme song! Once I imagined them telling their imperfect stories of the American Century, which let me send them everywhere I wanted to go from the Skipper serving in the PT boats alongside Jack Kennedy during World War Two to Ginger meeting Sammy Davis and JFK at Frank Sinatra’s house in Palm Springs, the book practically wrote itself. I did it in six weeks—six weeks of the most perfect happiness that I’ve ever known before or since.

GS: In Infinite Jest, a character’s father obsessively, religiously watches M*A*S*H until he all but uses it as a form of prognostication. Is Gilligan’s Island, or any other show, your M*A*S*H?

TC: Nah. In fact, a number of Gilligan’s Island fans just hated the book because my use of those characters was so opportunistic and casual. But you didn’t even have to be a fan of the show to recognize it was the spoof version of a morality play. It’s not an accident that “Ginger or Mary-Ann?” ended up as the basic philosophical question for men my age.

At one level, and I know and delight in the comparison’s absurdity, it was my goof on Joyce using The Odyssey to structure Ulysses. He once admitted he didn’t really give a damn about the framework except as a way of organizing the thing. At my much more modest level, I felt the same.

GS: Out of all the compulsory reading I did for my public education, only The Great Gatsby stood out to me as something truly special. What was your first encounter with this novel like, and do you recognize it as a Great American Novel?

TC: I once knew The Great Gatsby practically by heart, and I’m sure it shows. I have mixed feelings about its Great American Novel status because of course it’s beautifully crafted—my god, the command of incident! Nobody handled that better than Fitzgerald—but as a view of life, I think it’s piffle. Why should we root for this humorless and vainglorious man to break up what seems like the dull but not unpleasant marriage Tom and Daisy deserve? Who’s the real “careless person” who smashes up things and people to serve his own narcissism?

GS: In Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter, you’ve written an epic from the perspective of the titular character. What drew you to this character, and how did you approach writing a character with such a complex legacy while staying true to her Fitzgeraldian origins? How much of it is literary ventriloquism?

TC: Going back to your earlier question, one appalling thing about Gatsby as a character is his chilling indifference to the little girl Daisy and Tom have brought into the world. If he wants to break up their marriage, which he does, poor little Pammy ought to matter. And she doesn’t.

So I wanted to imagine HER life afterward. I wasn’t interested in writing a sequel—I mean, Gatsby never appears, and is mentioned only once by name in a throwaway line. So I killed off Tom and Daisy as soon as I decently could to let Pam voyage through the 20th century as an orphan. The image of the orphan, cut off from a famous past she can barely remember, was very important to me, and I also wanted her to have a pedigree that would resonate with American readers. You know, when Tom and Daisy’s daughter vents at age 86 about the Iraq War or Hurricane Katrina, she’s got a borrowed bit of stature on her side.

GS: How did Fitzgerald’s portrayal of Daisy as a mother figure or lack thereof inform your vision of the character’s daughter and her struggles with her past?

TC: I took it for granted that Daisy was too narcissistic to be a good mother. One of the book’s less obvious themes is Pam’s journey to forgiveness after hating and resenting her foolish, long-dead mom for decades. There’s more than one reason she describes her autobiography as the grandchild Daisy never had, and one of my favorite passages is when Pam imagines her living to old age as “Daisy Eisenhauer” and dying in Louisville on the night we landed on the moon.

GS: Are there any relatively recent films or TV shows that have grabbed your attention?

TC: I’ve retired from having to write about this stuff, which I do not regret. At a certain point, you get too burned out and alienated to be watching the same show the audience is, and that’s the end of your usefulness as a pop critic. But that said, The Good Place did just delight me. Even if you liked him a lot on Cheers, which I did, who’d have bet on Ted Danson to have such a marvelous late-life career?

GS: Do you find that your background and experiences in pop culture and nonfiction shape how you approach storytelling, or do you prefer to leave those influences behind when writing fiction?

TC: They all flow out of the same set of interests and predilections, obviously. Otherwise, you don’t write a novel based on Gilligan’s Island that manages to drag in Richard Nixon and send the Professor off to work in Los Alamos as a young man before he visits Tokyo in his dotage and turns into Godzilla. Or an appendage to The Great Gatsby whose octogenarian heroine is waiting to give George W. Bush a piece of her mind on her 86th birthday while reminiscing about her friendship with All About Eve’s Eve Harrington. Pam thinks the movie calumniated Eve, by the way.

In my case, I like to describe the difference between my journalism and my fiction as the difference between cooking and baking. When you cook a chicken, you’re choosing the frying pan, adding sauces or whatever—but it’s still chicken, and the chicken’s intrinsic interest predated whatever you do to it, whether it’s named Bob Dole or Madonna. When you bake a loaf of bread, you’re taking familiar ingredients—flour, salt, water, and Kalamata olives if you like pane Pugliese the way I do—and converting them into a loaf of bread that has never existed before. But it all happens in the same kitchen.

GS: What novel do you think deserves more readers? Why?

TC: There are so many! Impassioned essays about why more people should appreciate, for instance, Charles Portis—a writer I revere and have nothing in common with except, I hope, humor—are as ubiquitous in lit land as an interstate festooned with hopeful-looking KFC franchises. The difference is that drivers actually do swerve off the road to Denver for the opportunity to commune with the Cuhnel. Portis’s secret sauce is as yet unknown.

But one novel I like that few people even know exists is the forgotten Vance Bourjaily’s equally forgotten The Man Who Knew Kennedy. It was written right after the assassination and is a moving attempt to reconcile Kennedy’s charm for that generation with his as yet unrecognized dark side. The perfect George Clooney movie, in a way.

GS: If you were to write a third novel in the same vein as Gilligan’s Wake or Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter, what literary classic or pop culture icon would you turn on its head next, and why?

TC: I think I’ve worn out that vein, which may be unusually subject to the law of diminishing returns. I did used to joke that my next project after G-Wake was gonna be based on Clue. Hero: Colonel Mustard. Trauma: being gassed in the Great War.

GS: Have you been writing any fiction since 2011’s Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter?

TC: I have a novel I’ve been tinkering with sporadically for years, but I doubt it would find a publisher. And at my age, finding a publisher is the real long-distance event. I can think of one dear friend who has an international reputation and went through hell just finding someone willing to print his more recent novels. And to put it mildly, my own reputation is not international. But one tries.

GS: What can you tell me about the novel you’ve been tinkering with?

TC: The unfinished novel was a mock memoir by a disgraced former U.S. Senator who resigned under threat of expulsion for sexual harassment in the 1990s and has come to roost as a shabby professor of political science at a second-rate college in post-Katrina New Orleans. It was to be another kaleidoscope of history and fantasy—my hero hails from the great state of Ohidiana, which understandably boasts the fewest number of newborn girls named Diana: just imagine what high school would be like! But I largely abandoned it after realizing what hell it would be to find a publisher for a parodic but self-exculpating account of an old white dude with a zipper problem. I write for publication, not private pleasure, always—even though the private pleasure has not been inconsiderable along the way.

GS: One of Gatsby’s major delusions was that he could repeat the past. If you could repeat the past, what moment would you choose, aside from the wonderful time you had writing Gilligan’s Wake?

TC: I have a downright violent allergy to Gatsby’s notion of repeating the past and wrote Daisy in part to ridicule it. My Pam has had an often glorious life, but it’s one-and-done as far as she’s concerned. If you insist, however, there were happy times with my now former wife in locales as varied as Paris and Staunton, Virginia, that I wouldn’t mind revisiting.

GS: In an increasingly illiterate world, what, if anything, gives you hope?

TC: That every era finds the form of artistic expression that’s most appropriate to its own circumstances and yearnings. Hip-hop is the latest great example. There is no reason that “the novel” should be privileged more than any other creative form. Its 19th-century popularity and subsequent deification in 20th-century English departments were the result of two phenomena: 1) mass literacy and 2) Charles Dickens. Or Balzac, Tolstoy, take your pick. Two things you learn from writing about pop culture are 1) none of this is permanent and 2) whatever replaces it won’t necessarily be bad.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as editorial services, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

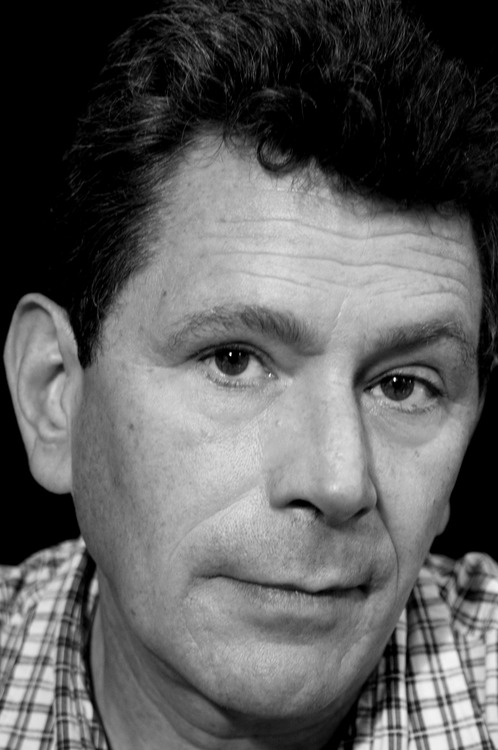

Tom Carson is the author of Gilligan’s Wake (a New York Times Notable Book of the Year for 2003) and Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter. He twice won a National Magazine Award during his stint as Esquire’s movie critic and was nominated twice more in the same category for his work at GQ. He has written extensively about pop culture and politics for the Village Voice, the LA Weekly, the Atlantic Monthly, and other publications. He currently lives in Louisville, Kentucky.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.