George Salis: When it comes to typographical hijinks, most people think of Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000), but such designs can be traced back to Lee Siegel’s Love in a Dead Language (1999), and even further back to N.H. Pritchard’s The Matrix (1970) and William H. Gass’ Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife (1968). Were you inspired by any of these works or did the structure of Apikoros Sleuth come exclusively from the Talmud?

Robert Majzels: Although the Talmud was the primary formal model, the possibility to experiment with form has been made possible by the more recent works of concrete and vispo. In Canada, bpNichol and M. NourbeSe Philip. We might also go back to William Blake, Mallarmé, and to Dada and Lettrism, which I like because of the combination of radical politics and aesthetics. I spent some time in China where, you know, poetry and visual art have always been inseparable, partly because of the nature of the written language and the importance of calligraphy, but also because of a different, less rigid understanding of the arts than the Western categories. A couple of examples: Bada Shanren (17th century), and Xu Bing’s book from the sky (1990). These last two were important to Claire Huot’s and my 85 project.

GS: For those who are unfamiliar with the Talmud and the Torah, what are the most important and relevant principles for reckoning with Apikoros Sleuth?

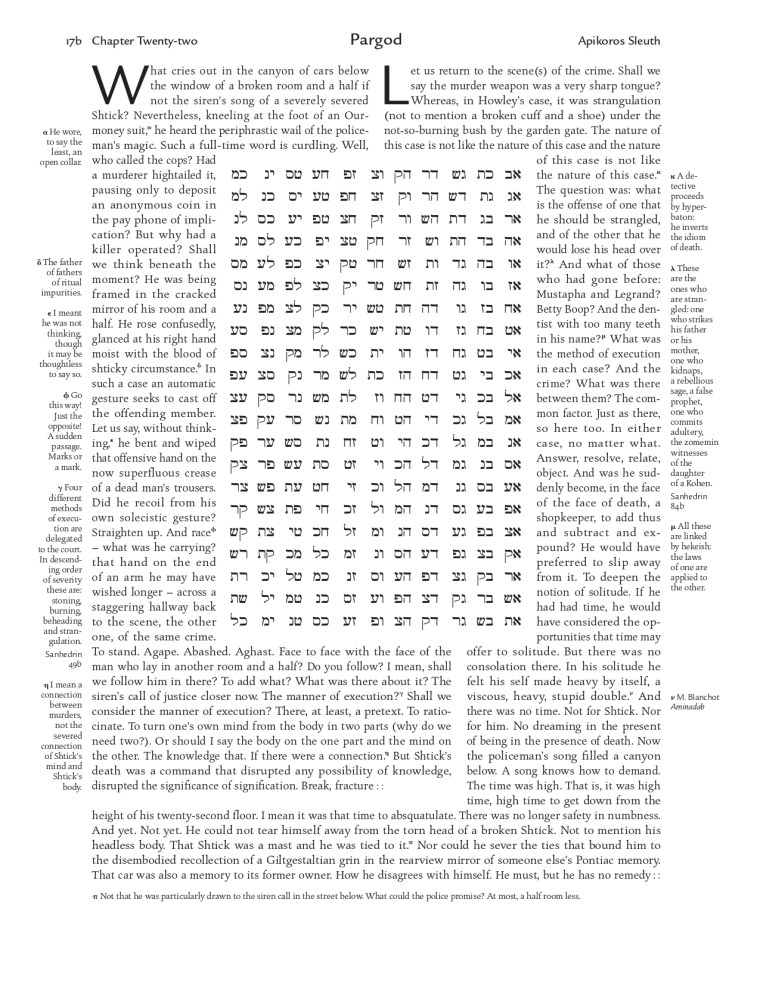

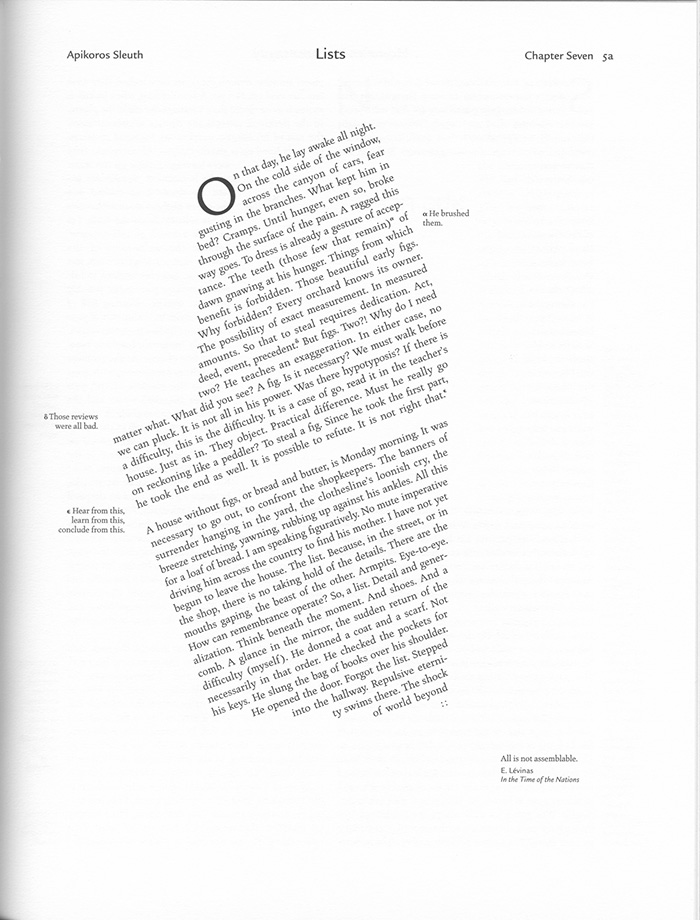

RM: The polyvocal nature of Talmudic inquiry is reflected in the physical arrangement of its pages, each of which contains a number of related commentaries and interpretive arguments, often disagreeing, by various authors over several centuries, arranged in columns and inserts around the original Mishna, a dense and difficult text. Because the Talmud is the inscription of knowledge which was for centuries transmitted orally, the links between sections are often associative. Linear progress is further undermined by continual digressions and rhetorical shifts. Finally, the dense elliptical style of the central Mishna and the Gemara commentaries, in the original Hebrew and Aramaic, results in a plasticity: the “body of the text” (a Talmudic phrase) acts figurally to further open up the signifying process. In working out the prose style of Apikoros, I have tried to reproduce something of that Mishnaic density and repetition. I used a number of recurring if decontextualized phrases commonly employed in classical Talmudic argument and exegesis.

Apikoros Sleuth actually follows along the Sanhedrin Tractate of the Talmud (one of 63 tractates). The main subject of the Sanhedrin is the attempt to describe the future “World to Come” sometimes referred to as “the time of the Messiah,” or paradise on earth. So, what will it look like, when can we expect it to happen, what should we do to make it happen, and who will get in? Strangely (or not so strangely, when we start trying to create heaven on earth), a lot of killing ensues, the Sanhedrin begins by defining the various capital crimes and appropriate methods of execution.

GS: What made you decide to use this form to tell a sort of anti-murder mystery instead of any other type of genre? Are you a fan of murder mysteries or did the structure lend itself to it more than others?

RM: Like the Talmud, the murder mystery is really about the mystery of death, and the concomitant issues of guilt, responsibility, justice, ethics. Formally, the murder mystery is the quintessential linear narrative structure: the rising tension to climax and denouement. That structure, which is unfortunately described as “realism,” is at the heart of the failure of our cultural imagination. It is, of course, not realistic at all, not an accurate representation of my life’s trajectory anyway. But rather than dismantling or at the very least, amending it, we tend to blame ourselves for our failure to live up to it.

[The grammatical sentence, the syntactical order, as we all know, is already structured in the same linear way to create the illusion of resolution and closure; hence Nietzsche’s claim: until we are rid of grammar, we are not rid of god.]

The murder mystery and the Talmud both engage in detailed argument in the quest for truth. The Talmud, however, complicates the mystery by its open-ended structure and the rhizomatic progress of its argument, thus suggesting the possibility of an aesthetic responsive to the limits of representation. The Talmudic form and method of inquiry can be described as the rigorous and relentless pursuit of truth and justice in the full knowledge of the impossibility of ever entirely attaining the goal.

GS: Certain phrases repeat in your book in new contexts and sometimes with slight changes in the phrases themselves. Can you talk about this and how you see it informing the book’s structure?

RM: Talmudic hermeneutics is a highly complex system, utilizing several levels of exegesis, from understanding a text’s plain meaning to gematria. Many terms and phrases have a specific meaning or purpose within the discussion and are used repeatedly in similar situations. For example, if a scholar writes the phrase, “a halakhah for the time of the Messiah,” they are responding to another rabbi’s stricture or punishment that is too harsh, not possible in the world we live in. Most of the repeated phrases in Apikoros are such Talmudic discursive formulations. I like them for their strange effect, and the repetition with difference. They create a kind of non-linear stuttering and profluence in the text from one page to another. Also, imitating the style of a literal translation of the Hebrew-Aramaic Talmud allowed me to approach what Beckett called writing without style (he decided to write in French because it was easier for him thus to write “without style.”)

GS: Can you discuss the Hebrew that appears in the book? In one Goodreads review, the following claim is made: “The Hebrew ranges between somewhat coherent and totally incoherent. The incoherent parts are either (a) complete gibberish made up by the author, (b) partial gibberish made up by author by putting together parts of Hebrew words that on first sight seem legit but when reading have no connection or logic, (c) ancient Hebrew words I don’t know, or (d) Aramaic, which I also don’t know.”

RM: The language of the Babylonian Talmud is mainly Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, with occasional Hebrew and even some Greek words, but all written in the Hebrew alphabet. I studied Hebrew as a kid, but not sufficiently to tackle the original Talmud without help. I used the Steinsaltz edition which includes a beautifully literal translation with copious notes alongside each original page, and a rabbi kindly proofread Apikoros Sleuth (once I was done with his copy, he burned it, as one does with heretical texts).

GS: There’s a healthy dose of humor in Apikoros Sleuth. Do you use humor in this book to balance out the academic essence of its structure and the darkness of the murder mystery? In short, is it a kind of coping mechanism or simply good fun?

RM: I don’t think of the structure as academic; it’s just different from the conventional forms of “literature.” Humo(u)r can be subversive, disrupting the genre-purity, taking the reader out of the intrigue, opening up the text (Bakhtin, Brecht). Comedy can be, as Colm Tóibín has written somewhere, very close to pure tragedy. He’s thinking of Irish theatre, but dark humo(u)r is also a very Jewish thing.

GS: In more than one place in the book, you write, “Have mercy on these lines.” Do you find that readers are more hostile to the type of books you write? How often do you think of the potential audience when writing?

RM: I don’t think of an audience when I’m writing (you might say the reverse is also true: audiences don’t think much about my writing). Occasionally I imagine a reader as someone smarter than I. Apikoros in particular was conceived as a kind of Kabbalistic ritual (after Abraham Abulafia). Writing, in Abulafia’s practice, was an exercise to pass through the 231 gates to paradise. The gates are composed of all the possible pairs of the 22 letters in the Hebrew alphabet (see the gates in Apikoros,chapter sixty-three, 39a). The book is the golem that appears merely as a byproduct at the end of the exercise, serving as evidence that the author has completed the process. Of course, Apikoros Sleuth is a heretical version of Abulafia’s teachings; hence a book to be burned.

GS: As the author bio on your website states, you’ve worked many different jobs, including “grocery store wrapper, lathe operator in a steel plant, taxi driver, hospital orderly, insurance appraiser, health clinic administrator, commercial and literary translator, and post-secondary teacher.” Have any of these jobs given you fodder for your writing or were they all just barriers to your own creative acts?

RM: I imagine everything one does or experiences in life is in some way fodder for one’s writing. Some things are more directly useful. The factory in Lachine, Québec appears in my first novel; in my second book, City of Forgetting, Che Guevara gets a job in an insurance claims department. Teaching literature and creative writing in a university for seven years probably helped me to think about my writing in ways I wouldn’t have otherwise, mainly in reaction against the way they teach writing in those circles, but I did meet and read the work of a number of interesting young writers. My work in literary translation has had a valuable impact on my own writing. I don’t make a distinction between translation and “original” writing. To dwell in another’s text, to struggle with diction, syntax, accent, tone teaches one a great deal about language and writing. Also, it can be a relief not to have to deal with the minor aspects of writing like plot and character, and to concentrate on the line, phrase, etc.

GS: Out of all the books you’ve translated from the French, is there one in particular that you’re most proud of or have a special affinity for?

RM: I’ve never translated a literary work I didn’t enjoy. I enjoyed all of France Daigle’s fictions, and I think For Sure, which I translated from her Acadian Pour Sûr is a magnificent work and certainly in the top ten of all Canadian fiction. I also enjoyed all Nicole Brossard’s poetry, not only because of the beauty of the originals, but also because I got to work with the brilliant poet Erín Moure in translating them.

GS: Apikoros Sleuth was given to me as a gift. If you could gift a copy of your book to anyone living or dead, who would you choose and why?

RM: Diogenes, because of his differences with Plato, and because he said. “The only place to spit in a rich man’s house is in his face.” But he probably would have used the book to wipe his derrière. Anyway, he’s dead so he’d have no use for it at all.

GS: What is a book you’ve read and think deserves more readers?

RM: There are so many, I don’t know if I could pick one. Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus; If Not Winter, Ann Carson’s translation of Sappho; Hawkes and Minford’s translation of Cao Xuexin’s The Story of the Stone (although it has had an abundance of readers in the original). Since we’re talking about Kabbalah and Jewish philosophy, one of my favorite books is Rabbi Nahman of Breslav’s burnt book. Nahman (18th century CE) was a Hasidic teacher of torah and the secrets of the kabbalist arts. As was the case for all kabbalists, his teaching was oral. With the passage of the years, however, as he approached death, his students begged him to put pen to paper in order to preserve his knowledge for future generations. After resisting their insistent pleas for a long time, he finally acquiesced and went off to write his book. When he was done, he gathered his disciples, presented the enormous tome containing all his secret knowledge and, to the horror and dismay of his students, he set the book on fire. When only ashes remained, Rabbi Nahman explained: “After me, there shall be no school.” (See Marc-Alain Ouaknin, Le livre brûlé.)

GS: Your latest two novels, kHarLaMoV’s aNkLe and deAd liNeS, form a utopian fantasy dilogy. What can you tell me about this pair? Is it informed by relatively recent events? How would you compare it to your earlier book, Apikoros Sleuth?

RM: I wrote kHarLaMov’s aNkLe during Trump’s first presidency, while Stephen Harper was PM in Canada. I had just quit teaching and wanted to break some rules and write something they couldn’t or wouldn’t teach. Hence the rejection of punctuation, and the drugs and terror. deAd liNeS is really about climate change and the end of this planet. These novels are more modest visually, partly because I have less access to printing and publishing technologies than I did with Apikoros and with the 85 books. But also I’m drifting toward less words, less pyro; more empty space as I grow old. I’m approaching completion (if such a thing exists, which I doubt) of the third volume (Laura) of what turns out to be a trilogy. This one imagines the citizens of Europe gathering and walking en masse, unarmed and without slogans or placards, into the heart of the Ukraine war to smother the war with their bodies. I don’t think it will end well, but it’s also a kind of twisted utopian.

GS: You were especially active in politics in your youth, even going so far as to support the underground democratic forces in the Philippines. What do you think of the current state of world affairs? Do you have much hope, and if so, where does this hope come from?

RM: Hope is a pimp. An invention of the oil companies to keep us busy recycling plastic. I think the obsession with the future is responsible in large part for the human destruction of the planet. In any case, our sun and planet have a finite existence, though the planet will certainly be unsuited to any form of life much sooner. In fact, the entire universe is destined to expand into frigid darkness. That’s not necessarily cause for despair. To live in a brief moment might be a reason to stop striving and competing and murdering each other, to relax instead and enjoy the view.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as editorial services, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

Robert Majzels writes from time to time. His work, a continuing exploration of the forms and ethical underpinnings of writing, seeks to undo or, at the very least, complicate genre classifications, because the way we tell our stories, rather than reflecting our lives, dictates the way we struggle to live them. However, as classifications persist, he can be said to be the author of five novels, a full-length play, a collection of poems with Claire Huot, and a number of translations, including novels by Anne Dandurand, France Daigle, and, with Erín Moure, poetry by Nicole Brossard. His website is here.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.