“Listen long enough to other people and all you’ll hear is the story you’ve only just now stopped telling yourself.”

Garielle Lutz’s corpus is a sphere turned inside out. No matter where you enter, you’re at the center. Perhaps it’s a way of saying she has no minor works. Each volume, each story, is part of the Work, a monolith of marmoreal and borderline surreal sentences. Every sentence is the center too, which can be, paradoxically enough, a lonely place. We are all our centers, and everyone else’s edges. Nevertheless, alwaysthemore, these lonely sentences can’t help but aggregate into paragraphs, narratives comprised of something akin to Lance Olsen’s narraticules. Misery isn’t the only thing that loves company, even when it hates it. Or is there some biological law at work? The mitosis of misery, the cloning of loneliness. All sentences distinguishingly the same due to their lapidary melancholy, their ancillary memory.

Worsted, recently reprinted by Calamari Archive, contains 14 fictions. Since her debut, 1996’s Stories in the Worst Way, Lutz has written about people peopled, unpeopled, and repeopled by themselves and others—will-o-the-wisp wives, heavied husbands, quibbling siblings, sudden children, and sundry personages outside the nuclear. The marred ages of marriages, the indefinitive vortexes of divorces. Mistified friends and stranger strangers. Worsted continues to thicken the crowd of the thinned out.

In some form or another, almost everybody is a mind’s eyesore. Bodies are not just vessels but a sewerage necessary to keep something like the soul going before it goes. “She’s a lukewarm purée of a girl with bedroom eyes and a bathroom mouth,” and “There was a rubicund delicacy to her adult acne. It looked embossed on her professionally.” These are only the flesh wounds that yawn wider still via a pestilential penchant for existential abstraction. For example: “My wife, one of them anyway: her body in those stone-gray, encompassing dresses had no real way of explaining itself. She seemed to move at some remove from her footfalls. You never knew how close she was getting,” “It’s darker in a room that has people in it than in one that doesn’t,” and:

Looked at in a different way, it’s all well and good to fault yourself for thinking that you have another life when you’re not quite asleep, when sleep is hovering just above you—and that that one’s the life in which you’re most at the beck and call of who you more likely are.

And me?

I’m just like everybody else.

Only never at the same time.

As it is with Lutz’s own body, so it is with the body of words that comprise language. In othered words, Lutz interrogates or upturns or inverts as much as invents new meanings from fatigued terms and phrases: “‘As a fraction of language, wife looks and sounds just a little too sure of what it’s meant to be meaning. It’s got too much of a hold on its meaning for its own good. Husband doesn’t even sound as if it’s fit to refer to a person. It sounds like something extra you have to put on just because you’ve been told to, even though you feel you’re already fully dressed,’” and “One night, later in my rickety fifties, wracked on the toilet again, folded in on myself, chest pressing against thigh, chin nested between bushy knees, I rotated the plastic bottles within arm’s reach on the floor until I had arranged a little library of cleaning-product-label life lessons: ‘Avoid contact with skin’; ‘Do not mix with other products.’ I let the bottles and their edicts boss me around until I put myself back to bed.” Most of the above quotes are from the opening title story, which, at 43 pages, is one of her longest.

Garielle Lutz’s corpus is a sphere turned inside out. No matter where you enter, you’re at the center. At the center one expects to find the heart, but you can’t find what you’re already in.

The stories’ settings are also familiar in their strangeness, focused as they are on the dungeony drudgeries of domestic life in renter-occupied domiciles and other liminal spaces. The greasy shackles of fast food chains. Crass classrooms and their administrational orbits. Only rarely does nature peek out in a couple of stories, almost in the manner of foregone salvation, revelationally so at the end of “The Water Table,” featuring a windy and winding, but not winded, sentence that could have originated in the night-bidden soul of Joseph McElroy. “Rules for Tenants” presents the most unique story structure, that of said rules in Lynchian leasese, more specifically the industrial apartmenthood witnessed in Eraserhead. One example is section 13a:

Visitation policy. Two (2) women at a time, if on record as unswerving sisters of copious soul, may be admitted to any unit whose lessee is a lustless, watery-eyed male—provided that conversation flourishes within five (5) minutes of admittance. No men are to be admitted to a woman tenant’s apartment under any circumstances. Children are to be regarded, at best, as prompts to remember that we all unsettle and ebb.

If writing is a war against cliché, as Martin Amis put it, and it is, then Lutz is our five-star general of plentiful Purple Hearts, having lived to tell us ailing tales, stories in the best way. Whereas most authors who write in an all-encompassing voice, regardless of the POV, doom the reader to eventual boredom, Lutz’s voice is so singular, so piecemeally original, that it continues to replenish itself in thine eyes, even if the author admits that she’s running out of words. This after decades, though. With over half a million words in the English language, and many unborn ones awaiting their utterance, as well as the tarnished lexicon genie-lamped into brilliance by her hands, I think and hope that Lutz can run out for words rather than of them, rather than lapse into this character’s mentality: “But she wasn’t much of a reader. A book was just page after page of redistributions of the language.”

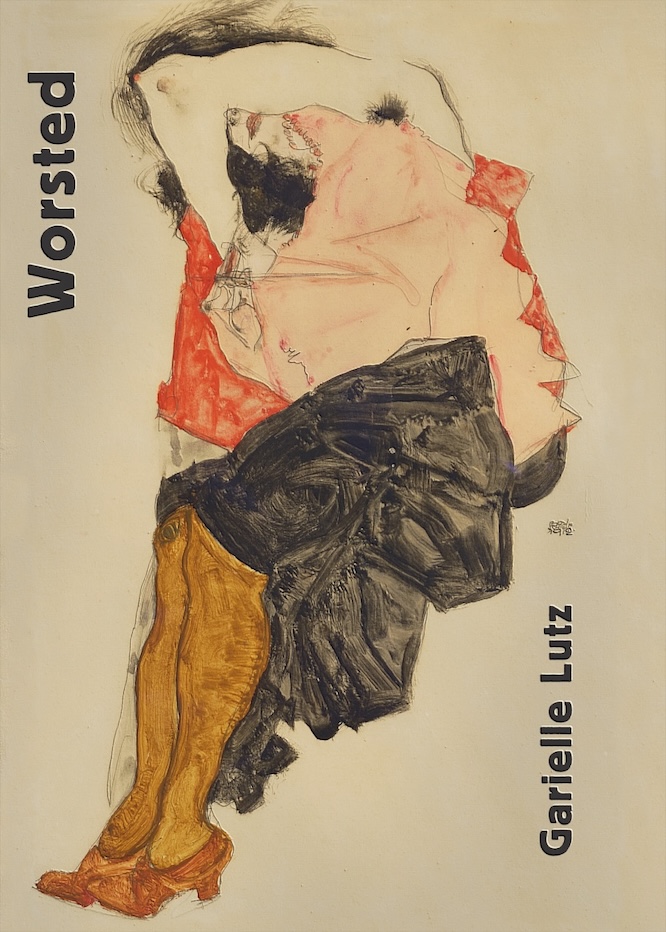

My Calamari Archive copy has ink more light gray than dark black, the words on the verge of fading altogether, and I do mean all, together. Lutz’s writing deserves the deepest ink—each letter a nightscape. Making up for this lack is an Egon Schiele cover, which fits the collection perfectly and is an improvement on the original SF/LD edition. The new artwork depicts a disheveled dish of a woman who covers her face with her antecubital crook and, in doing so, reveals her pink-nippled elbow and her hirsute armpit, a stinky stand-in for the minge. The implication reinforces one of Lutz’s lessons: hiding one thing reveals two others—hydra-go-seek.

Lutz’s corpus is an inside-out turned sphere. No matter where you exit, you’re uncertain of your center. Any reader worth their cost in shadow will be bettered for having read Worsted.

Listen to an in-depth discussion between George Salis and Garielle Lutz on The Collidescope Podcast:

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below and Morphological Echoes. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.