George Salis: Steven Moore argued that novelists make the best critics, and supported his argument with examples of criticism written by Alexander Theroux. As it happens, Theroux’s brother Paul said on Charlie Rose that critics are like eunuchs in a harem, that they see the act being performed yet can’t do it themselves, and are envious of it. At the age of almost 50, you switched from criticism to fiction and wrote Passing Off. Do you feel as if your experience as a critic better prepared you for this transition? Could a case be made that critics make the best novelists, to reverse Moore’s assertion?

Tom LeClair: Being a critic and teacher (though not of creative writing) gave me some closely examined models and methods. Knowing what my subjects would be in that first novel—two passions, basketball and Greece—also helped. My early problem, from criticism, was being too expository. Fortunately, my two subjects required a good bit of exposition. Choosing an unreliable first-person narrator who was unliterary helped with the expo problem. Also the somewhat natural linear plot. Still, the manuscript went through quite a number of revisions, some suggested by other practicing novelists.

As for your general question about critics becoming novelists and the reverse, I don’t have much of an opinion, though having novels rejected most of my life has probably made me a more sympathetic reviewer. There is a mismatch, though, between the kind of fiction I praise and the kind I write. As my students used to ask me, “Why don’t YOU write a Systems Novel of the kind you praise most highly?” My answer is, “I’m no genius.” Many of my novels play within popular forms. I sneak in ecological or political or economic content with the probably faulty assumption that the “no game, no gain” unreliable narrators may require a second reading during which that content becomes more noticed. This assumption is more true of the five Keever novels than the three others which are more straightforward about, respectively, Kurdish refugees, lead, and Lincoln.

I used to do a lot more reviewing 10 or 20 years ago than I do now. Generally I avoid “around the house and in the garden” novels (DeLillo’s description) because this former critic finds little to say about them. After 40 years of reviewing for the NY Times Book Review, I was negative about one such novel…and never got another assignment.

James Elkins is one example of a critic who wrote a really interesting novel, Weak in Comparison to Dreams. It’s a book you might want to give some attention to.

GS: Speaking of your friend Don DeLillo, could you paint the picture or set the scene of your first meeting with him in Greece? In your Substack, you mention how you sought him out for an interview despite his lack of popularity at the time (although he did have quite a few novels under his belt: seven if you count the pseudonymous Amazons). DeLillo was in Greece researching The Names, of course. Where exactly did you guys meet? Was there a feeling from your interactions that suggested this would turn into a lifelong friendship? How familiar were you with his work up until that time?

TLC: DeLillo didn’t want to be interviewed. He agreed because he didn’t think I’d travel to Greece, but I got a travel grant from my university. When we met on the steps of the Grand Bretagne in Syntagma Square in Athens, he handed me a card that read “I don’t want to talk about it.” It was partly a joke. He used to hand the card to visitors to his unlikely expensive apartment in New York City. His wife was an executive at Citibank, and Don was in Athens because she was working there. As it happened, two years later my family rented an apartment in Kolonaki that looked onto his back balcony. He was very helpful to the newcomers and liked my teenage children, several of whom claim they influenced White Noise. He left Athens a few months after we arrived.

I could not have anticipated that we would be long-time friends. Living in Cincinnati, I’d see him once in a while in NYC, and we did correspond. I reviewed White Noise and went to Greece to write In the Loop. He was not impressed. Later I reviewed Underworld and Cosmopolis. We saw much more of each other when I moved to NYC in 2008. He always ordered spanakopita and tzatziki for lunch. He has never cared much for what has been written about him, and very much discourages a biography.

Although Don never gave me any writing advice, I consider him a mentor. I don’t mind being called “DeLillo’s caddie” even if what looks to be his influence—say, terrorism—comes out of my own experience, some of which I describe in Passing Again. Of all his books that I wish I had written, the first would be—no surprise—The Names, though I do argue with its statement about the Parthenon at the end of Passing Off.

GS: Yes, Don DeLillo strikes me as the person for whom only the words matter—the words, the sentences, and their accretion. I often think about what he said when prodded about the potential dwindling of his fame: he always prefers to be in the back of a room, observing. The mark of a true writer.

In what way do your children claim to have influenced DeLillo’s White Noise?

TLC: My then wife and I gave a lot of freedom to our three children to say whatever they wanted at the dinner table, so—since DeLillo never had children—they believed the cross-cutting dialogue of the Gladney children was influenced by our dinners with Don. My daughter is even more specific, recalling that she told him about missing the school bus and taking taxis to school, which one of the Gladney girls does (as I remember). Such “influences” are the danger of sharing meals with an author.

Me, of course, I’m Scott, the caretaker of Bill Gray’s reputation in Mao II. Not really, but DeLillo does use a passage from our interview in the novel.

GS: In Passing Again, you tell your alter- or anti-ego Michael Keever the following: “You think you have a problem with the author? How would you like feeling you’d been created by—and had to compete with—the greatest living American novelist?” Ironically enough, my friend, the writer Michael Brodsky, doesn’t believe writers can be friends, a sentiment that I’d like to prove wrong. Still, there can be envy. There can be, as you say, competition. However, competition can be a catalyst for working harder at one’s craft. Was talking about writing off the table with DeLillo, or did you two settle into a sort of respectable comfort over the years, one in which that talk came without extra baggage? Can you unpack some of those feelings you touch on in Passing Again? I can imagine the original dynamic being akin to the looming parent and the son who wants to make him proud, perhaps futilely so. There’s something of a happy ending here, considering he blurbed one of your books, which must have felt like a knighthood.

TLC: When I met Don in 1979, he was an established novelist. I was a provincial academic who reviewed one of his novels and messed up the protagonist’s first name. It was 11 years later when I took leave from my university and moved to Athens to write my first novel. In my essay “Two on One,” I joke about being in competition with Don and Coover, but I never really thought of it that way. When we met, we talked about sports, politics, others’ novels—almost never his or mine, never about craft. We’re close enough in age that there’s no paternal dynamic. I just keep reminding him that if he gets the Nobel he promised to take me to Sweden with him. Passing Again is a fiction. You can’t trust anything anyone says in there. I reviewed The Silence in ABR. If you want to know my true feelings about Don now, take a look. Readers have thought of him as “cold.” I always found him just the opposite. I met a lot of novelists coming through my university. Don is one of the nicest, the least egotistical. One thing we shared, along with having a Catholic education, was, I think, a sense of incredulity that people from our backgrounds—Bronx immigrant, VT hick—could become writers. How successful we were at it didn’t affect the basic fact that we were lucky. He won’t get the Nobel now, but he was happy to see his work in two volumes of the Library of America. It was like he’d arrived at the university…where I’d been most of my life.

GS: In End Zone and Underworld, DeLillo compares football and baseball, respectively, to the nuclear powers that be. David Foster Wallace does something similar with tennis in Infinite Jest. Have you noticed anything nuclear or radioactive about the sport of basketball?

TLC: You got me with that one from deep left field. Basketball is more like ordinary life than either of the other sports. You can play at the neighborhood park. You can talk to your opponents while you play. It’s called the city game because it resembles crowded sidewalks. In football, the players are trying to mash each other. In baseball, they are distant from each other. In basketball, players try to be close to their opponents without much physical contact. I actually don’t read many sports novels, but I’d find it odd if they were put to political use. Passing Off and other Keever novels have ecological aspects, but “nuclear”? Pro players rarely even get in fights.

OK, time for game 2 of the NBA Finals to start.

GS: Indeed, the way you treat basketball as a metaphor for life has a strong affinity with Updike’s Rabbit series, which you reference multiple times throughout Passing Again. But I want to talk about the structure of your latest and possibly last novel, or at least last Passing novel (as stated on the French flap). The structure is not conventional, and comes across as part collage, consisting of audiotapes, blog posts, photos, etc. You also include samples from your past works, which allows Passing Again to act almost like a Tom LeClair reader. It’s even mentioned in the book that one purpose of the project would be to interest readers in your past novels. Can you comment on this and explain how Passing Again took shape in general?

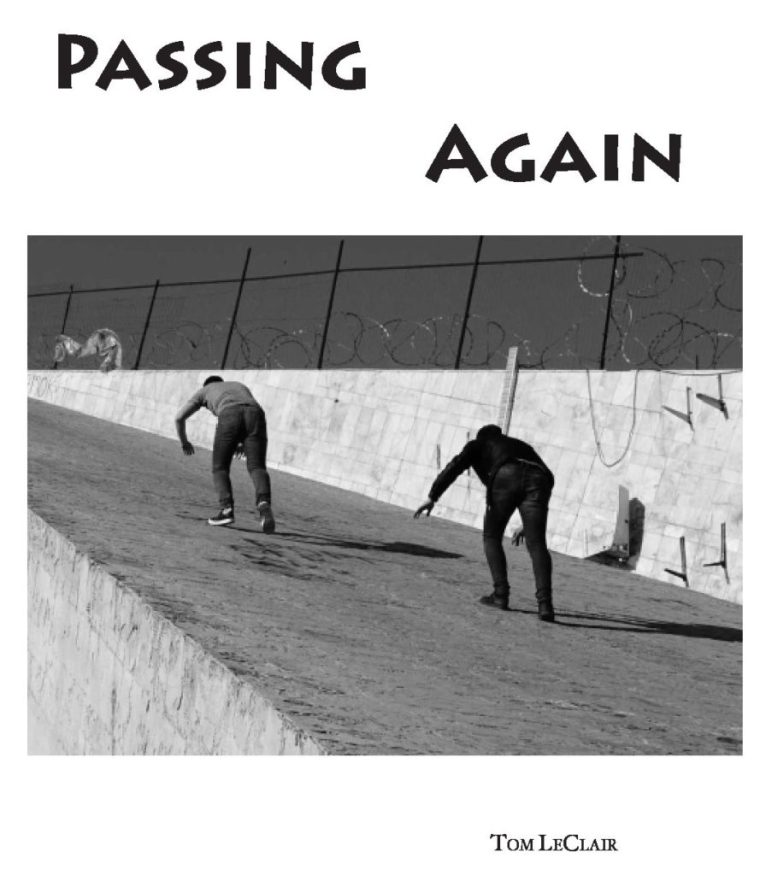

TLC: I was living in Warsaw during the pandemic lockdown with the photographer whose images appear in Passing Again. I wanted to use and write about photographs. I also wanted to write again about Greece, where I met the photographer. I had the piece about LeClair and Keever called “Passing Strange” now on Substack, and I wanted to see what would happen if that relationship between author and character continued. Mostly, though, I think—now—I wanted to play, play as I never had before, push unreliability to unpredictable limits and see if I could make an interesting collage out of the materials I had, which included my very recent and then present life. To borrow a title from Gaddis, write A Frolic of His Own. I didn’t really expect it would bring readers to my other novels because I didn’t think Passing Again would ever be published. But a small press heard about it and wanted to do it, so there it is. What interests me still is the relation between Keever and LeClair, to which I have returned in my “straight” memoir Passing Down. How is it that writing about a character through so many books could change the writer? How might the writer begin to imitate the character? Maybe not a subject that will interest many readers, but it and the other pieces of which Passing Again is made are what I had in Warsaw. If a lot of pandemic novels were about hunkering down, this one is about busting out, having fun—that last a contested word in the novel. Maybe an excess of fun, my modest shot at an art of excess. My “last shot,” a phrase that comes up a lot in the novel.

Something else I had: after Passing Off was published in English, I took it to some Greek publishers. “We can’t publish this, a novel about destroying the Parthenon,” one said. ”Someone might read it and try to do it.” That remark is what propels whatever plot there is in Passing Again with Keever back (now with friends) to save the monument.

GS: What the Greek publisher said reminds me of how Stanley Kubrick stopped screening his adaptation of Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange after it inspired copycat acts of violence. In cases like these, how responsible, really, are artists? Should we censor ourselves because of potential and/or actual psychopaths? I’m remembering Steven Pinker’s distinction: violent art and media don’t cause violence, but it just so happens that such content is what already violent people are attracted to. So, in that sense, a work of art can color or shape a violent act, but the essence of the act is already in motion in the sick mind.

TLC: You can’t depend on the sick mind to realize that the plot against the Parthenon in Passing Off is made up by Keever’s wife to sell books, this fiction within my fiction to, in a way, parody such books. The media has enough violence that artists shouldn’t worry about imitating it or attending to it. Decades ago, ricin was in the news, used, if I remember correctly, in the Middle East. A terrorist in my novel Well-Founded Fear plans to use it in the U.S. Since then, I note with some nervousness the occasional reports of ricin poisonings in the U.S. I just hope that when I return from Europe in a month, I’m not detained by ICE for having written Harpooning Donald Trump.

On the credit side, I’ve warned against dangers with my Museum of Lead in The Liquidators, the environmental hazards of ship-breaking in Passing On, and the perils of Algeria in Passing Through. I can’t claim to be soteriological (a Greek word for you) like Richard Powers is, but given the few readers of Passing Again I’m not too worried about the Parthenon.

GS: Ahhh, ελληνικές λέξεις (Greek words). On my last trip to Greece (the majority of which was funded by the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing), which consisted of three months of intensive research across the mainland and multiple islands, I finally started to learn the language, including that original alphabet, the alpha-beta, and so I was delighted to come across actual Greek words in Passing Again and sound them out. Once I move there permanently in a few months, I’m sure “Γάμα την αστυνομία” (Fuck the police) will come in handy at some point. Anyway, how much Greek have you picked up while living in Athens on and off again for the past 40 years? Have you ever studied it formally? What are some of your favorite Greek words? For myself, I’d nominate μυθιστοριογράφος (novelist) because it so beautifully encapsulates the chief obsessions of my own novels, myth and history, fantasy and “fact,” etc.

TLC: “Permanently,” you say? Ever lived there in the winter? I spent three there, and I wouldn’t do it again.

Before I went to Athens to teach at the university on a Fulbright, my family and I took some private lessons. My then wife and I were very bad, as I was in French and German. But then I was married to two Greek women, sequentially not simultaneously, and I didn’t really need to learn Greek. So I just picked up what I needed to insult guys on the basketball court (momothrevtos) and order food (horice kremethia). When people asked me how my Greek was coming along, I told them I was being careful, learning one new word a year. One of the better ones is lipee. You call an office and ask for Iannis. Lipee, the secretary says. “Gone.” Could be out for 15 minutes or be dead. A future Substack piece addresses the subject: I wanted to be as ignorant as my hoopster, experience the country as an athlete, without words. Then meelou Ellinikah.

I should say I know enough to read your GR alphabet. Yeah, mythistorima is a good one. But probably not as useful as Ti na kanomay when all the transport is on strike.

GS: You say you wish you’d written The Names most of all. As it happens, The Names did crop up into my consciousness while reading Passing Again, even though they’re still very different books. Out of all the DeLillo books I’ve read, and I’ve read the majority of them, The Names is his most dialogue-heavy, which almost serves as a counterpoint to his wanting to write lapidary sentences that evoke the ancient chiseling of Greek words into stone. Passing Again is also dialogue-heavy. And it shares a Greek setting, obviously. And then there are the overlapping themes of questioning truth, broken relationships, etc. Did you have any of this in mind as you wrote Passing Again, or is it all coincidental, or perhaps subconscious?

TLC: This one gives me pause. The dialogue I credit to Gaddis in J R. In the contemporary sections, most of the pages are either dialogue or photos. I was tired of writing descriptions, though they creep in, for example, at Tiryns. Let’s see, all novels are “questioning truth,” more specifically all of mine with their unreliable narrators. “Broken relationships?” My life offered three divorces, so I didn’t need DeLillo for that. Kolonaki setting. Both DeLillo and I lived there. Here may be the difference, possibly subconscious. DeLillo is, in ways, a mystagogue, one looking for experience that has some of the qualities of his childhood (not just in The Names but in many works). For example, he calls the Parthenon a “cry for pity.” To whom? I love the history of Greece, but I don’t feel God or the gods there. For the foreigner, Greece is mysterious, and that I liked, its resistance to me—but not mystery with a capital M. For a long time, I have wanted to be Wallace Stevens’ “Snow Man.” Nothing that is not there, the nothing that is. Humans as athletes, thinking animals. So I see Passing Again as a representation of “Me to play,” as the epigraph has it—not as any kind of reply to The Names. More like The Photos. Maybe that can be seen in the sections that were taken from earlier writings. They were conventional narrations. The contemporary is dialogue or pictures. There is no Owen Brademas figure. Just a couple of guys trying not to fuck up, again.

Or so I remember it.

GS: And photo is yet another Greek word, meaning simply: light. But going back to everyone’s favorite POS, I mean POTUS: As someone who has diligently protested in front of Trump’s Tower of Babel, and even wrote a book about him, were you surprised that he was elected again? Do you really think there’s a risk of ICE giving you trouble upon your return to the States? Trump is possibly the most dunked-on (basketball reference unintended) president in history, so why would ICE single you out? Although I suppose this logic doesn’t apply to our illogical times, nor to the machinations of fascism/authoritarianism, which is currently in vogue not just in the States but globally. You’ve been around the block. Would you say the country is in the worst state it’s ever been in politically and culturally?

TLC: Not surprised, not the way the polls were running in the last month. The dinged ear in PA saved him. One day in front of the Tower, I got a visit from two Secret Service guys. They asked how long I would be there, and dummy that I was I said “until five o’clock” instead of “until this fool is no longer resident of the White House.” The three other regular protesters assumed our photos were in the files. Given the Service’s sensitivity after two failed attempts, I’m a little worried that my title might imply that I’m a threat. Can’t assume everyone has read Moby-Dick. In this worst of times, I envy your leaving. My problem is I’ve been around the block more than once, and my body needs to stay in the USA for insured medical care. Otherwise, I might go to Albania, which welcomes Americans for a year with no visa problem. Could probably get good GR food there.

[A few hours later, Tom sends another email.]

Yeah, you got me with that question about The Names. I read my chapter on the novel in In the Loop, probably for the first time in a decade or more. Orality versus literacy, right brain versus left—they’re there in my analysis. “Conversation is life,” Axton says. But I still think I was not updating The Names directly by way of Passing Off, which was admittedly influenced by DeLillo’s take on life in Greece. Volterra, the manager of images in The Names, doesn’t get much play. The photographer and images are crucial to Passing Again as an alternative to both written and spoken language. At the end, LeClair becomes a critic of images…as he has in real life with his recent reviews of photobooks.

GS: I’m glad to have spurred this, Tom. The parallels are fascinating. As for the photos in your novel, I had incorrectly assumed that they were all ultimately taken by you, but many of them were in fact snapped by Kinga Owczennikow, the dedicatee of the book in question. You said you two met in Greece and that you wanted to write about photos, but why this photographer, why these photos in particular, some of which appeared in Photo Vogue Italia?

TLC: Before I answer the question: DeLillo gave me the secrets of Ratner’s Star, including left brain, right brain. I thought that also worked in The Names, but when he read my book on the subject, he said no. So the influence went as such: my writing in error about The Names influenced myself in Passing Again.

GS: Ratner’s Star is one of the few DeLillo’s I’ve yet to read, but years ago I found a very rare paperback edition at a hole-in-the-wall thrift shop in Central Florida. I hear that the book’s ambition is, to some degree, legendary.

TLC: I found a paperback copy of Amazons on a rack outside a store in the Mani. But to answer your earlier question: She sat down next to me in Kolonaki Square (there’s a photo in the book taken later) and we started talking about her camera. She was leaving that afternoon but sent me some of her photos which I much admired. We began to correspond and arranged to meet again in Greece, which the book is sort of about (minus Keever). I wrote an essay similar to the ending of the book about her work—which explains why this photographer. Not long after, I decided to leave my wife of 20 years. Kinga reminded me last night it was the 6th anniversary of that Greek meeting. We were out celebrating the arrival of her first book, Framing the World, for which I wrote an introduction, which I’ll send you.

I sense that it (the interview) is coming to an end—and there’s something I’d hoped you’d ask me about, since we have traipsed rather far at times into the weeds. That’s the online supplement to Passing Again, to which readers are alerted when they “finish” the work (the paper text). The URL is here.

When I used to interview novelists, I’d ask them at the end if there were any questions that they’d hoped I would ask. So here’s a possibly simple one for “you.”

At the end of Passing Again, readers curious about the resolution of its story are offered an online Supplement. What was your idea about that?

Passing Again is hybrid in several ways, so I wanted to extend that to its being as both printed text and online text. What LeClair and Keever do after Athens is only indirectly revealed in the paper text, so the first item in the supplement is the photographer’s account of their meeting in Mexico City where they resolve issues about their “archive.” She gets the last word and photo in the narrative. After that, the Supplement is much more memoir than novel: an interview with LeClair and three essays, two of which were published and therefore factual. In fragmentary fashion, they also tell the post-Athens story of LeClair and the photographer. I suppose I thought the essays would highlight the fictionality of the paper text. Little did I know, then, that a couple of the essays would be in the long version of my actual memoir, Passing Down, in which Keever surfaces yet again with three stories. Not even in “real life” can I seem to escape him, one of the themes in Passing Again.

GS: Your inclusion of hyperlinks and the book’s structure as a whole put me somewhat in mind of Steve Tomasula’s work, which aims to blur the line between a physical book and digital counterparts, particularly in VAS and his most recent effort, Ascension. Steve also emphasizes the physicality of books and designs them in such a way that they defy digitization. So, these almost dueling aspects of the physical and digital are something I certainly appreciate in art, and so it is in your Passing Again.

Ever since I started The Collidescope in late 2019, I’ve been asking all interviewees a staple question regarding neglected books. What’s one “invisible book” that deserves more readers and why?

TLC: Maybe it’s too recent to be neglected, but given its crazed ambition I predict it will be. It’s James Elkins’ novel Weak In Comparison to Dreams, the first in a series of five that he has been working on for decades. Briefly, it’s like Pynchon with photographs of burning forests. Your readers can find my review here. If they don’t trust me, they can look up the even more enthusiastic review in the Washington Post.

GS: What about a novel from the 20th century? Does anything come to mind?

TLC: I’ll raise you a century: Harold Frederic’s The Damnation of Theron Ware published in 1896. About a clergyman who becomes an example of this century’s extrinsic identity, the praise and attention of others a forerunner of How to Make Friends and Influence People.

GS: What makes a good review? And do you have any specific pet peeves related to poorly written or conceived reviews?

TLC: Ever since I was a National Book Award judge in 2005, I’ve thought of myself as a judge when reviewing. Recognize what James called the donnée, research the precedents, see all the evidence, and apply the law of literary ambition. By that last I mean not judging a novel or book of stories against this season’s hot properties but against great works of the last few decades. Even when I used to be paid to write reviews, I also thought of myself as a critic, perhaps because writing academic criticism is how I started opining about books. I was able to do this and keep getting assignments from some very good venues (The Nation was my favorite, though the lowest paying) because I had a day job and was not a freelancer. My approaches and values did not serve me well when much book reviewing became an adjunct of publishers’ promotional departments in the last decade or more. Given reviews now, you might think no bad books were published. I knew better after reading through the slush submitted to the NBA. The more I think about this, the more I admire The Damnation of Theron Ware, about the dangers of making one’s identity around pleasing crowds.

GS: Is there a critic or book of criticism you admire? Martin Amis’ The War Against Cliché: Essays and Reviews 1971-2000 was a formative book for me, as well as certain works of literary criticism by Christopher Hitchens, including his writings on Lolita and The Great Gatsby, even though he looked at them through a sociopolitical lens. More recently, I greatly enjoyed reading all four volumes of Paul West’s Sheer Fiction.

TLC: Four volumes by the same author? You shame me. I doubt I’ve read a whole volume by any critic. When I was writing academic criticism, I’d look up books and essays about someone like Pynchon I was discussing, usually to use the authors as foils. Way back then, the British critic Tony Tanner was a model with his City of Words. Not exactly a literary critic but an important influence was Gregory Bateson and his Steps to an Ecology of Mind, systems thinking. John Leonard, former literary editor of the NYTBR and the Nation, was an early influence on my reviews, maybe one reason he used to assign me books. The critic I most admired was William Gass, but one had to be careful not to absorb his rhythms. Although Christian Lorentzen has not published a book, he’s a current reviewer of fiction that I will go out of my (ignorant) way to read. The writer I most dislike: Jonathan Franzen for both essays and novels.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as editorial services, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

Tom LeClair is the author of critical books, novels (most recently Passing Again), and hundreds of reviews and essays in national periodicals, some of which were collected in the ebook, What to Read (and Not).

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.