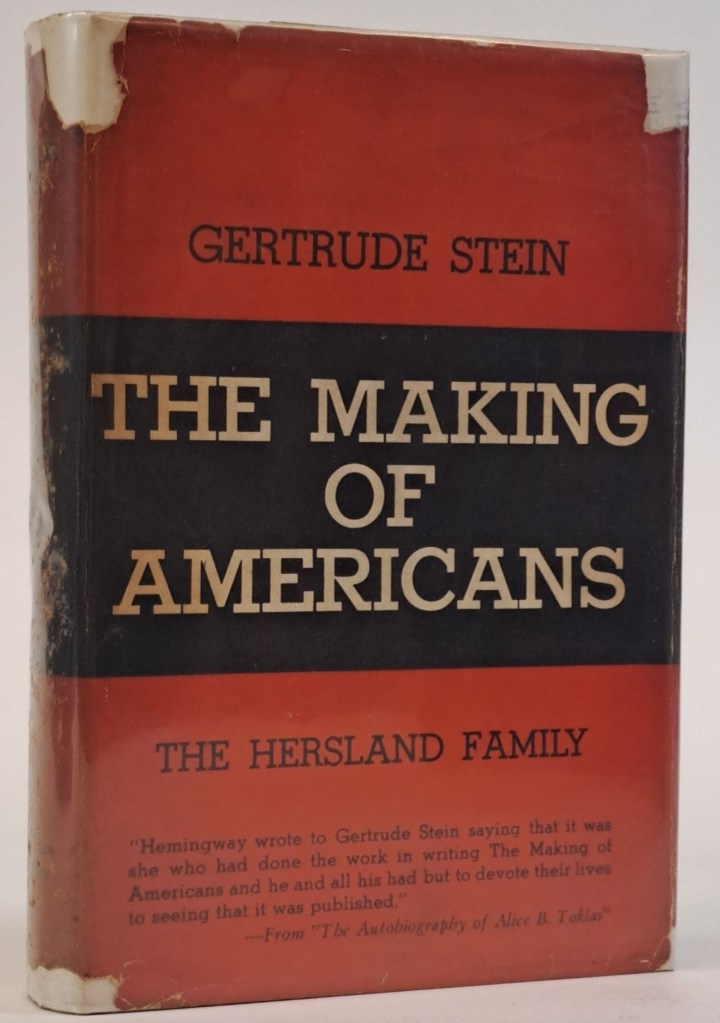

When people ask me to explain – their euphemism for “justify”– my lifelong obsession with Gertrude Stein, I immediately get defensive. For I know they come at me with disdain and doubt. How do I counter their attitudes and disparagements? And what is their reason? And what is mine? Why do I continually go back to her novels, her memoirs, her plays? Is it her wit? Her insight? Her singular style? Fairly recently, my go-to answer had been: “It’s the way she reflects consciousness.” Having spent my summer re-reading her magnum opus The Making of Americans (which turns 100 this year), I think that answer’s bunk. No one’s mind follows the loopy patterns of Stein’s epic novel. Not even her idiosyncratic brain. Oh sure, we repeat ourselves – breathing, eating, complaining, to name but three lifelong habits. And yes, we obsess in our thinking. Sometimes, we get clearer. Sometimes not. And Stein understood this. Stein understands.

“There are some who realise it of each thing that it is a pretty thing, there are some that realise it of each thing that it is an ugly thing, there are some who realise it of each thing that it is a funny thing…”

Does that circular phrasing drive you crazy? If not, allow me to continue. Let’s say the “thing” she’s referring to is Life. This passage (page 686 in TMoA) is, for me, quintessential Stein, Stein as soothsayer, Stein as literary tease. By repeating the same sentence over and over then swapping in a different adjective each time, Stein reminds us how perception is colored by personal views. First, she offers the clichéd polarity: a glass half full (“pretty”) and a glass half empty (“ugly”). Then she jumps ship entirely by abandoning the binary for a third alternative: the absurd (“funny”). But the passage doesn’t end there. Not by a long shot.

“…there are some who realise it of each thing that it is a tender thing, there are some who realise it of each thing that it has a pretty color, there are some who realise it of each thing that it has a pretty shape…”

Stein both sticks with and alters the repetition. She shifts from the initial black/white model, throws up her hands, then dives headfirst into an even quirkier pool that – to my thinking – acts as a passageway to the possibilities available in one’s point of view. Is “tender” emotional? “Pretty color” superficial? “Pretty shape” lascivious? That’s how I’d interpret this passage today. Yet why does Stein state it in such a roundabout manner? Why not simply write “emotional” and “superficial” and “lascivious” outright? Or do we shortchange our own minds by abandoning the associative for the dictionary? What’s to be gained by using allusive terms?

Much of The Making of Americans has to do with Stein’s wish – and frustration at her own inability – to tell it like it is. It being everyone. For Stein wants to know everyone, to define them, to deconstruct every human she’s ever encountered to their core, to classify then apply every possible stereotype then to delineate every variation of every stereotype then to engender it then to degender it. You might think there’s something preposterous, even wacky, about such a goal. But I’ve come to wonder whether to describe every potential character, to categorize everyone as a personality type isn’t something we’re already actively pursuing. Are you an introvert or an extrovert? A Sagittarius or a Libra? A top or a bottom? In capitalism, we call this the market demo. What are we if not our algorithms? Our checkboxes? (I loved when Stein had me pondering whether I was a “dependent independent” or an “independent dependent” for pages on end in TMoA.) And when people turn to A.I. for recommendations re: movies, books, podcasts, restaurants, music, aren’t they in essence admitting they see themselves as part of some category of people, some subsection with universal likes, dislikes, and curiosities. If our crazed pursuit of computer logic isn’t driven by a blanket disregard for the uniqueness of individuality, what is? Stein goes on…

“…there are some who realise it of each thing that it has a meaning, there are some who realise it of each thing that it is a queer thing, there are some that realise it of each thing that it is an unpleasant thing…”

Like I said. Stein knows. Not everyone believes there is meaning. Right, nihilists? Not everyone believes in the sexual spectrum. LGBTQIA+, represent! Others just like to complain. Your numbers are legion! Yet the beauty of The Making of Americans – despite being written a century ago – is that Stein sees us all. Or at least she’s furiously trying to. She’s constantly reflecting the present world back to us from the past by being as expansive and exhaustive and forward-looking as she possibly can. Her attempt is overwhelming. Her persistence remarkable. Her clarity periodic but also startling. At times, I could only read a couple of pages at which point I’d be forced to go back and start again. Stein continues…

“…there are some who realise it of each thing that it would be a nice thing if it were in a room with simple furnishing, there are some who realise it of each thing that it is a thing a nice thing when it is in a room which is not a very light one…”

Basic materialism. Anti-materialism. Excessive materialism. The Shakers? The cellar-dwellers? You choose. For what is an American outside of the products they choose? But remember…

“…there are some realising that each thing is part of a story any one can be telling about anything…”

Or in other words…

“…there are some that are realising each thing is a nice thing if it is exciting to love that thing…”

Which is another way of saying…

“…in a way then every one has it in them to feel something about things being in being existing.”

Because you are a that as well as a who and it’s up to you how to feel about that. Such is the wisdom of page 686. Now read the rest of the novel.

Drew Pisarra has directed numerous plays by Gertrude Stein, including Yes is for a very young man at the Brooklyn Arts Exchange, Ladies’ Voices at Portland State University, P.S. 122, and St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, Three Sisters Who Are Not Sisters at Lewis & Clark College, and Curtain Raiser at The Red Room. He was also the lyricist and book writer for a musical adaptation of her children’s story The World Is Round in collaboration with the composer Gisburg.