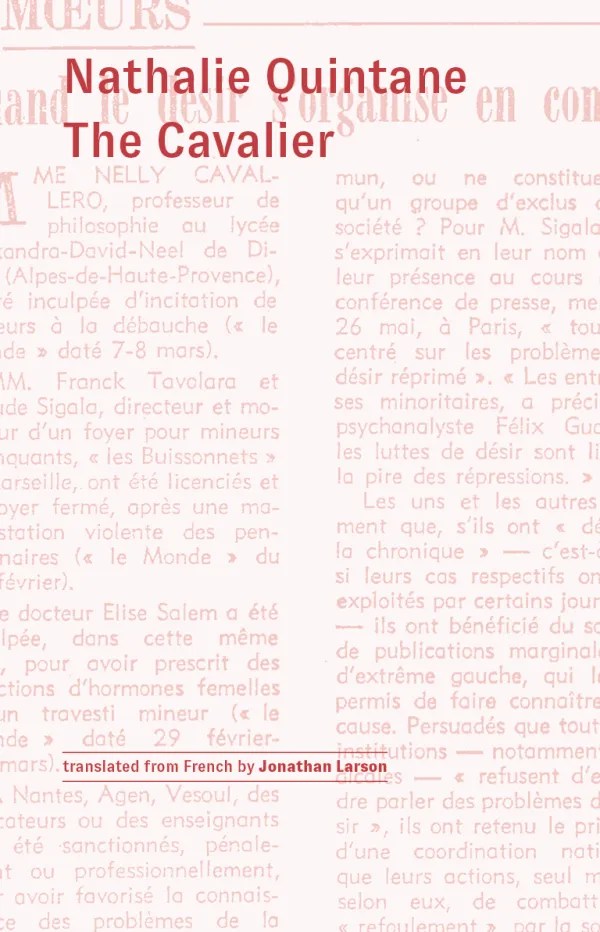

The Cavalier by Nathalie Quintane, translated from French by Jonathon Larson and published by Winter Editions, is a book strange and appropriate. Strange because of its difficulty, beginning with its genre. It claims to be a memoir, and Nathalie Quintane appears as herself as its author, but it reads like a postmodern novel, featuring impersonal close narration, narrative self-consciousness, shifting points of view and chronology, and, most importantly, narrative and thematic fragmentation. Call The Cavalier a book, then, or a text; the fusions of technique matter only to the formation of the text itself.

The text is a quest. Or a mystery. Quests necessarily begin in the past, as do mysteries. There is incitement, obfuscation, varying narratives and settings, murky motives, and cover-ups. The story takes place in a marginal area and Quintane is a speaker from the margin. The incitement is the events in France of 1968 when workers and students struck, rioted, and nearly brought down a regime, forcing De Gaulle to rely on his armored troops to retain control of the country.

Quests, maybe, resolve in future.

The ideals of 1968 failed.

After the immediate failure, some of the militants, aware they could not defeat the system, abandoned it by rejecting conventional roles and going to work in factories or to live in primitive rural communes, discarding “work” altogether. These attempts, confused and naïve, were made by the educated—intellectuals and students—not the workers. Maybe the workers knew enough to know better, knew the rebellion had failed, knew the future was the status quo.

Quintane tries to unravel the fate of a teacher in the 1970s, Nelly Cavallero, who was, apparently falsely, charged with indecent assault of a minor. And there are others, including Francoise, who knew Nelly, and who lost their teaching licenses and livelihoods. Quintane traces through commentary, headlines, film, and the file of the original charge to create or attempt to create a sense of the case and its cultural context. That context is damning in its conservative, anti-feminist, anti-abortion repression and its reflection of French society, and particularly the French educational establishment, as a closed, suffocating system. Teachers, Quintane observes, are “yesterday’s good students.” The implication is any attempt to reform or rebel against the system is doomed to preserve its pervasive, formative elements.

Quintane is also contextualized by the system though her context is confused. She is mistaken for a Parisian when she is in fact a banlieusarde; she is an Agregees lycee instructor by profession, but by both her school and location, a provincial. These categories are important, but difficult to understand in an American context: a banlieusarde is a suburbanite, but America’s suburbia does not carry the cultural, social, and economic impoverishment of the banlieus. Likewise, an American may live in fly-over land, but even that derogatory term doesn’t convey the profound alienation of French Provinces from Paris, the center of it all, a relationship Quintane describes as “colonial.” An Agregees lycee instructor is not the equivalent of an American high school teacher, but enjoys a cultural and social status more akin to the respect and position once held by the now-vanishing tenured university professor, before, of course, America decided to destroy education.

These definitions and confusions are significant because their exact calibrations indicate the precise social location of an individual in a static French system; while in the U.S., it is the soft haziness of social definition—we’re all middle class; working class is coal miners, not pink collar or service workers; everybody could or can or will be rich—that strengthens and prosecutes the neoliberal culture and state. In France, one is trapped in decline and immobility by a static identity; in America by all the opportunities that are somehow always just beyond reach.

The utopia of the generation of 68 has come and gone as have the confused, naïve attempts at an alternative: “they lived through the final utopia, that there will be no more utopias, that the world as it is…cannot endure another.”

Culture as expressed by political leaders is a series of gestures as vapid as Obama’s reading lists.

The accusations against the radical teachers are similar to the accusation Meursault did not sufficiently love his mother.

Education—progressive, regressive, or reformed—goes nowhere.

Even analogy fails.

Yet security and the security services seem always on the increase.

And the cavalier, when he finally appears, is not the man on horseback the reader expects to bring action or purpose or resolution—he is something else entirely, some construct of a confused joke, as all the incitements and charges and punishments seem the result of some confusion of a demand for sexual and social liberation and a reality of social and sexual repression.

So the text ends.

Stops.

And never tells the reader, the reader who has experienced this fragmented text, which is better—some confused, naïve attempts which change nothing or the static spectacle of a neoliberal system with real victims.

Greg Mulcahy is the author of Out of Work, Constellation, Carbine, and O’Hearn. His last book, First Trilogy, is available only as an ebook because publishers on two continents dared not bring it out. His next book, Driscoe or Second Trilogy, is forthcoming from Fiction Collective Two in Spring, 2027.