George Salis: Thank you very much for agreeing to an interview, Jamin. I not only admire your films but also the gumption it takes to spearhead these beautiful works of art through sheer force of will, so to speak. I’d like to start by asking the following:

What are some of the formative books that have contributed to your sense of storytelling and imagination? Did you have any books in mind when working on your latest film, Myth of Man? Perhaps there’s a reading list, however long or short, that informs the picture’s philosophy and fantasy? And if you need to answer these questions in the language of film rather than books, then by all means.

Jamin Winans: Thanks, George! I appreciate the kind words. “Sheer force of will” is pretty accurate, haha. To your questions: When I was quite young, my dad was great about reading to us. For me, it was Tolkien, C.S. Lewis’ Narnia tales, Jules Verne, Shel Silverstein, and many others. But I would say Tolkien and Lewis had the most lasting impressions. I also grew up in church and it would be absent-minded not to acknowledge the Bible and the saga within as having a strong impact on my sense of story.

But film more than literature has always been the biggest influence. We didn’t have a TV when I was a younger kid and so anytime I saw a TV or a movie screen I didn’t take it for granted. Cinema was absolute magic to me. I was a kid in the 80s and 90s, so it was the American movies of that era that made the biggest impact. All the commercial hits like Back To The Future, John Hughes movies, Beetlejuice, Ghostbusters, Star Wars, Terminator 1 & 2, and anything with any sort of sci-fi/fantasy angle dug into my soul and never left. It’s funny because we think of those movies as mainstream, but the studios would never take a chance on any of those original ideas today.

As I got into my teens, my mind was completely opened to cinema as an art form. I fell in love with more daring filmmakers like David Lynch, Terry Gilliam, Terrence Malick, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, and Michael Mann. To my surprise, I also fell in love with the silent era. Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Chaplin, and Sergei Eisenstein really taught me much more about the potential of cinema versus other mediums.

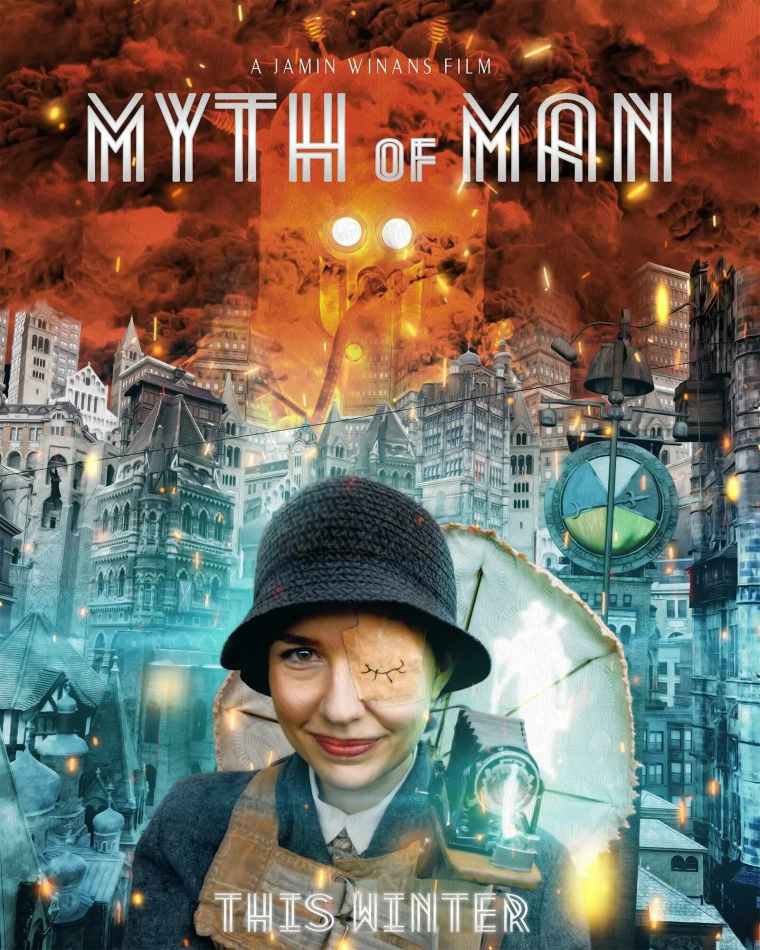

Our most recent film, Myth of Man, being a film without dialogue, was no doubt influenced by silent film. That said, there was no one film or filmmaker I was looking to. It’s just a language I developed over years as a filmmaker. When you’re younger in your craft, you look more to specific works or artists as a guide to give you permission, to tell you what you can or cannot get away with. But now I find myself in my own world and just follow my heart rather than think of other works or filmmakers.

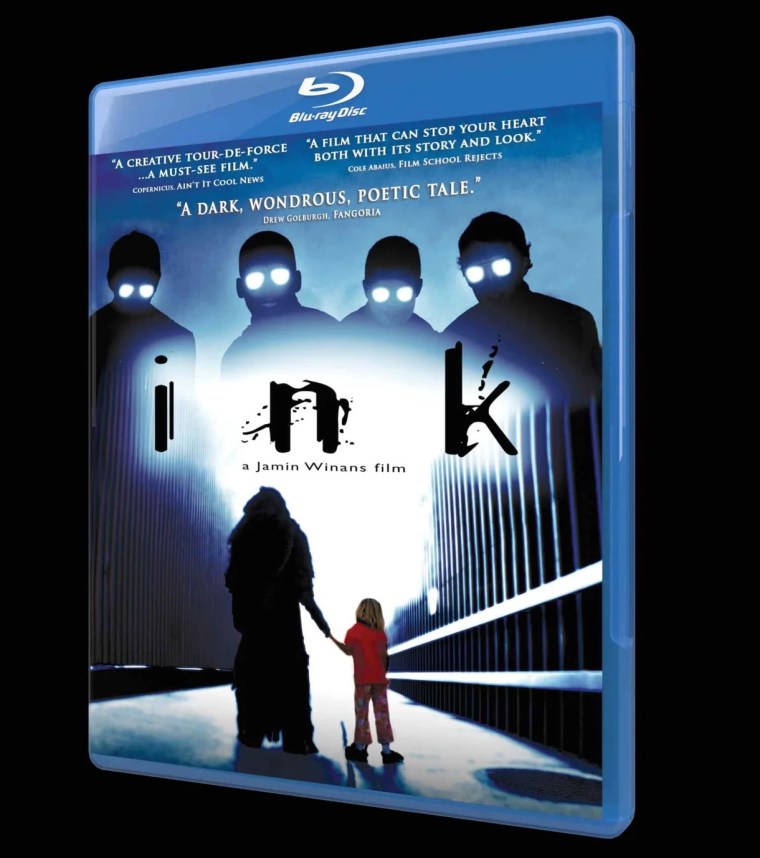

GS: It seems as though we have had fairly similar trajectories in our experience with film, as with probably most budding celluloid storytellers, except I chose the arguably easier, lonesome act of writing novels rather than making films. Your Ink score became one of the on-repeat scores for the composition of my first novel. So thank you for that continued aural inspiration. And I’m sure Myth of Man’s soundtrack will prove equally as useful to me.

But yes, the connection between your latest work and silent films is undeniable. Of course, the phrase “silent film” is almost a misnomer, seeing as these pictures do have soundtracks, some of which are more bombastic than a traditionally “sounded” film. Myth of Man is silent for a specific reason: the protagonist is both deaf and mute, and it’s perhaps this reason why the boundary between silence and sound in the film has curious moments of porosity, in which we can hear threads and shreds of voices, among other things, the life of the city. Can you comment or reflect on this choice, rather than choosing to have a definitively silent film with one of your always wonderful scores? I suspect it has something to do with your penchant for intimately intertwining the music into the action, the emotion, of a given scene.

As it happens, I just saw The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari for the first time at Cinobo Όπερα here in my new home of Athens. The film featured live music by pianist Stathis Anninos. A superb mixture of unconventional, staccato piano and cosmic synths. 105 years after that film’s release, almost like a microscopic version of the handprints within caves that are separated by thousands of years, we have your silent film, Myth of Man. Do you think something about the way films were conceived, something special, was lost after the transition to talkies, and do you think Myth of Man recaptures that lost essence?

JW: Our sound and music choices were based on the idea that our lead character Ella could not hear or speak. However, she still has an interpretation of sound that’s in her mind. So the sound in the film reflects more of her feeling and experience than the literal world. Kiowa, my wife and producer, was the master behind that sound.

I do think something was lost when the silent era faded and talkies came in. The possibility of dialogue allowed filmmakers to be a bit lazier with their craft. Rather than fighting for ways to express an idea without words, they could now just put the words in their character’s mouth. The silents depended on using ingenious techniques in composition, movement, light, set design, montage, performance, etc. When the talkies came, you could see the trend shift to more or less filming plays. Of course, there were still some great innovations after the silent era, but it wasn’t the same explosion of innovation and experimentation you previously saw.

GS: Can you tell me about a silent film that you think deserves more viewers, and why?

JW: Yeah, great question. Most silent films that survive today are worth watching. Probably my favorite silent film that is well known to film historians, but not to everyone, is F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise. More than anything, the story is just beautiful and has real emotional power 100 years later. Additionally, it’s an artistic and technical marvel. Murnau was so bold and intelligent, and filmmakers today owe a lot to him, though they may not know it. Germany produced some great talents in that time, including Fritz Lang and Robert Wiene (The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, as you mentioned).

GS: Thanks for the recommendation. I see that I have Sunrise on my Letterboxd to-watch, but I’ll try and bump it up that very long list. I’d like to discuss the visual aesthetic of Myth of Man. I’ve seen a handful of people online compare it to the video game Bioshock. I don’t know if you’re a gamer, but that’s one of my all-time favorite experiences within the medium. I also noticed some parallels, however superficial, between Myth of Man’s aesthetic and Coppola’s Megalopolis, two films that are grand self-funded labors of love. Are these surface-level comparisons pure coincidence, perhaps even happy accidents? Of course, the comparison to steampunk as a general aesthetic is probably inescapable. Ultimately, how did you go about crafting the look of your visionary world from scratch?

JW: You’ll be disappointed to know that my video game knowledge ended with the NES. We had to look up Bioshock when we heard that comparison several months ago because we didn’t even know what it was. So there wasn’t an influence at all there. Megalopolis was actually made after Myth of Man, but released before, so that wasn’t an influence either.

We didn’t set out to make a “steampunk” movie, but quickly realized that’s what it would be considered and we were good with that. I’m told it’s actually more “dieselpunk” than “steampunk,” according to the experts.

When I was a younger kid, I either wanted to become an inventor (I loved gadgets) or a ventriloquist (I was weird). Turns out filmmaking was sort of a combination of those things. The fusion of fantasy and the mechanical keeps coming out in our films. Though the driver for the ideas is always allegory. It’s all fun, but it’s there to serve a bigger story.

We started pulling references for Myth of Man starting back in 2011, if you can believe it. A lot of the ideas just came from traveling a lot and meeting unique characters along the way. We knew we wanted the world to be a combination of numerous cultures and time periods. A lot of the buildings themselves are photogrammetry of buildings throughout Europe, Asia, the U.S., and the Middle East. And the technology of how the city runs has its own complete backstory and logic, though that’s not covered in the film at all.

The costumes were all obviously retro and futuristic, spanning the 1860s and 1980s to some unknown time in the future. Ella has a 30s quality Chaplin-inspired look, but with contemporary touches. Seeg is a war vet whose look combines the Civil War era and the 1930s. Boxback is mostly 80s punk rock and Caley is 1930s. But all have hints of a time that hasn’t happened yet.

GS: Lovely. Andrei Tarkovsky defined cinema as a mosaic made of time, and you’ve done that on a very literal level with this high degree of eclecticism. A term I often use to describe a specific type of literary work, and it can certainly apply to films, is maximalism. Myth of Man is maximalist in more ways than one, especially considering the many handcrafted props and costumes, not to mention the 3,500 visual effects shots. You and your wife have taken the act of filmic creation into your own hands, figuratively and literally. Inspiring. And a decade-long project is nothing to sneeze at. I myself recently finished writing my sophomore novel after an equally Odyssean amount of time. I must emphasize that these long-term acts of creation require a unique disposition (who knows how many artistic aspirations are lost to not only time but so-called practicality or simply ground to dust under the slave-wage mindset of capitalism), so I’m wondering what drove you to keep going, what helped to sustain the passion at such a high intensity for so long? Conversely, what were some bouts of frustration or doubt or hopelessness that you had to deal with, if you don’t mind sharing?

JW: There were countless challenges along the way. The script itself took a long time to write. I knew I wanted to push the boundaries, and we also weren’t going to have a word of dialogue. I was writing the score simultaneously with the script, knowing that so much of the experience was going to be captured in the score and the sound design. This back and forth took a lot of time and I was banging my head against a wall more than once.

However, the hardest period of the filmmaking was in 2019. Kiowa and I had spent over a year prepping the film in Budapest, Hungary. We started shooting there in the Fall of 2019. Things were going decently, but we began having problems with a couple of our cast. After six weeks of shooting (about 40% of the film), it was becoming clear we wouldn’t be able to finish the film with our lead actress. We had to pull the plug, and since the character Ella is in every single scene, we lost about 98% of everything we shot. We were on a very tight budget and that was about the lowest point on any film we’ve made. We knew we would have to start over and we had no idea how we were going to do that. However, throwing in the towel wasn’t an option.

We were also producing a documentary at that time so we came back to the States to work on it at the beginning of 2020. Our plan was to finish that shoot and start Myth Of Man again. We were shooting the last of the interviews for the documentary in March of 2020 when schools and businesses started shutting down.

We made the decision to have everything from Myth of Man (props, costumes, etc.) shipped to the States from Hungary and we regrouped in the States. Finally, a year later (in 2021), we had recast and started shooting again. Fortunately, that shoot went very well and our cast was wonderful.

As you mentioned, we had approximately 3,500 visual effects shots and it was only Kiowa and myself with our friend Danilo helping us part-time. We were in post-production for three and a half years. We actually quite enjoyed that process; it just took about twice as long as we expected.

To our surprise, keeping the passion really wasn’t a problem. We knew that the film was saying something beautiful and that does a lot to keep you going. Every day really was a privilege to essentially paint and create both visually and audibly. We definitely had our technical battles along the way, but all in all it was a joy to work on.

GS: That decade of dedicated work has been immortalized because you’ve brought this amazing film into the world. Something like that can’t ever be taken from you. And now the film will have a life all its own in the eyes of viewers, including viewers who are waiting to be born a century from now. Okay, if you’ll allow it, I’d like to take a detour with a playful question: My name in Greek is Giorgos. Recently, at a café in Athens, I was speaking to my buddy Giorgos about the filmmaker Giorgos (or Yorgos) Lanthimos (every Tom, Dick, and Harry in Greece is either named Giorgos or Giannis, by the way). Giorgos told me, Giorgos, that Giorgos started his career by making music videos for cheesy romantic pop songs in the late 90s. I had no idea. In the spirit of this revelation, please choose a song for which you would make a music video. Tell me why that song in particular and what the music video might look like.

JW: That’s a fun question. One of my favorite songs is Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. Not the first song you think of when you think of a music video. But it’s actually a song that tells an epic story with a whole rollercoaster of emotions. More than anything, it just captures the beauty of the human spirit. It has joy, humor, sadness, triumph. It’s just an awesome piece of music. There was actually an incredible short film/music video made with the song in 2000 by writer/director/animator Eric Goldberg. His interpretation is wonderful and quite funny.

If I had all the time in the world I would be happy to make a video of Rhapsody. But I can’t tell you what it would be…just in case I do get all that spare time.

GS: A fine choice indeed, Jamin. In fact, I grew up watching Disney’s Fantasia 2000 (released five days after my seventh birthday), of which Goldberg’s animation is a part, and was mesmerized by it from start to finish. I rewatched it for the first time in a long time last year and it’s still so magical, something of the peak of American 2D animation before everything became cookie-cutter 3D and Don Bluth, perhaps the closest thing to an American Miyazaki, fell by the wayside. Just one more mark of shame on American culture among endless others.

Speaking of American culture, such that it is, what are your thoughts on the state of modern films? Have you seen anything that excites you or fills you with hope for the art form’s future, or is it as much a wasteland from your filmic perspective as it is from my literary one? Maybe there’s a country or movement that you look toward for that fulfillment?

JW: It’s an interesting time for film. We’re in the era of “content” rather than “cinema” and a lot of creators and audiences alike are chewing through “content” mindlessly. The producers don’t value what they’re making and the audiences don’t value what they’re watching. So we’ve landed on something like an assembly line of meaningless production and consumption of gray slop.

Studio blockbusters are always based on well-established IP (Marvel, DC, Disney, etc.). Though a lot of talent goes into these movies, there are few chances taken. Then there’s the streaming class of movies (originals from the streamers), which are today’s made-for-TV movies. Again, there is legit craft behind a lot of these, but few have real invention and soul. And finally, there’s the “indie” or “festival” film, which has become its own genre. Festivals have become largely political entities that prioritize specific messaging rather than the art of cinema itself. And so there is less groundbreaking cinema coming from that curation process in recent years. But in all these categories, there are exceptions that break through.

Of the great films and filmmakers out there, they’re often hard to hear about if you’re not searching. People have allowed social media companies to determine what they read, watch, and listen to, and there is nothing organic about it. If you “discover” something on social media, it’s because someone paid to put it there. Organic, word-of-mouth exposure has been largely snuffed out. Sharing something with your friends or followers has 10-20% of the reach it once did. So the massive challenge that a film has today is not falling into obscurity.

To answer your question, I have seen some great films over the last few years. Nothing immediately comes to mind as a film that I thought was truly groundbreaking, but often that doesn’t become apparent until years later. There are a lot of filmmakers (and many American) I love who are working right now; we’re just in an environment that’s hard to thrive in. Of course, that’s always been the nature of art and commerce. Starving artists have always been a thing; it’s just different challenges in different times.

GS: Well said. Slop seems to be the defining word of our current era, especially a new kind of waxy gruel: AI-generated images and video. The following is from your website: “Many people are confused about the current capability of AI. At the moment, AI is not capable of producing anything close to this film. The post-production process on Myth of Man took 3.5 years to finish 3,500 shots using only Blender, After Effects, and camera tracking software.” I remember people thinking that, based on its trailer, A24’s The Legend of Ochi used AI-generated imagery, when in fact it used practical effects. On one side of the spectrum, we have Guillermo Del Toro, who emphasizes the handcrafted aspect of filmmaking and says he’d rather die than use AI (Hayao Miyazaki, when shown an early example of generative AI, called it an “insult to life”) and then you have Paul Schrader, who often posts AI-generated pictures of himself with the Michelin Man and claims AI can write better and faster scripts than humans, better and faster film criticism, etc. Where do you fall on this spectrum? When will we start seeing pictures of you with the Keebler Elf?

On a similar note, your documentary Childhood 2.0 is only five years old, but a lot has happened since, including the advent of AI generation. How do you see this affecting both young and older kids as they use ChatGPT for their schoolwork and as their therapists, etc.?

JW: “Waxy gruel” is even better! We’ve tried to keep our association with the Keebler Elf quiet for years, but to no avail.

We definitely lean strongly on the Miyazaki side. What most people associate with “AI” (LLMs and generative AI), we think of largely as a parlor trick. It does something that is no doubt impressive, but it creates the illusion that it has some level of intelligence or reasoning, but it has none.

When it comes to professional filmmaking, generative AI isn’t currently usable for anything we would want to do. Yes, you can create something, but you can’t create something specific, which is pretty damn critical. It’s a slot machine that you pull, then pray you get something remotely close to what you want. The truth is, you will never get what’s in your mind because it can’t read minds, and there is no real control or consistency. I don’t know how far off fine controls in generative AI will be, but I question if it will even be possible.

I’ve spent the last year thinking a lot about this, but my conclusion is that what is currently called “AI-generated art” is no doubt “an insult to life,” as Miyazaki says. No one is creating AI art. Art, by definition, is something a human being creates to communicate with other human beings. Prompting AI is outsourcing a vast majority of your individual human creativity and soul to a blending machine that steals other people’s work. The human being is just pulling the slot machine and calling the result “art”. It would be like creating a music playlist and convincing myself I’m a composer.

I think “AI” tech can be useful for certain tasks within filmmaking, but not today’s version of video generative tools. A tool like Roto Brush inside After Effects is good if you want to rotoscope quickly (cut images out of the background). It’s possible that there will be other useful tools within software that can speed up specific route tasks, but we wouldn’t use a tool that outsources the creative decision-making. Arguably, almost every part of filmmaking is creative decision-making, so that doesn’t leave much room.

I suspect, although there are all kinds of AI slop dumped online, most people really don’t want this. Sometimes it’s funny for memes and the like, but when it comes to the things we truly value, I think most people want to know they’re experiencing the work of human beings. Value follows scarcity, and there’s nothing scarce about AI-generated imagery, writing, music, etc.

Regarding our film Childhood 2.0, yes, we’ve talked about this quite a bit. If we had all the time in the world, we would probably do a deep dive on the effects of AI “friends” and “therapists” on kids. It’s truly a disgusting prospect. It seems there’s a concerted effort to ensure that kids and adults alike have as little human contact as possible and are as self-consumed as possible.

GS: I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask about your longstanding creative relationship with your wife, Kiowa Winans, a type of relationship that’s exceedingly rare and special. I don’t think many couples would be willing to sell their house to fund a dream art project, for instance. Can you reflect on this dynamic and how it has affected the way you make films?

JW: When we got married, I’m pretty sure Kiowa took pity on me and realized I was going to have a very tough road ahead of me unless she helped. I barely earned a high school diploma and she has a law degree, so make of that what you will.

It was a bit of a risk to start working together, but it clicked immediately. Kiowa didn’t have any experience in film, which would intimidate most, but she never flinched. She just jumped in and figured out how to produce very quickly. And “producing” on our films is not at all the same type of producing most films have. In our first couple of years working together, Kiowa became a production designer, costume designer, and sound designer, among many other jobs. She eventually taught herself 3D (Blender) and has become an incredible VFX artist. She’s extremely confident and competent.

To your point, yes, she and I have gone all in on this together. Her fingerprints are on every aspect of the films artistically and also how we have lived our lives. The biggest effect she’s had on our films is through her courage. She champions bold and risky decisions, both artistically and economically and that has been monumental in making the body of work that we have. It’s a truly rare quality in a partner and spouse.

GS: In films like The Frame and Myth of Man, there’s an overlapping reaching toward and a grappling with a higher power, perhaps in a conventional sense, but also the power that is inherent in the act of artistic creation, in which all artists are the gods of their cosmoses. Can you reflect on this? I myself am a skeptic in just about every way yet when I’m writing I have deep moments of what can only be called spirituality. It’s a spirituality rooted in the real, in the words that contain etymological worlds, for instance. You mentioned growing up in a religious household, so does that at least partly account for the spirituality in these films?

JW: I’m with you on your deep moments when writing. There’s something to that and I think it’s worth asking ourselves more questions to better understand the source of that feeling. I’ll be a little elusive with this question because I don’t like to define our films or my perspective on their meaning too much. Cinema and music have such a powerful ability to reach uncharted territory in our hearts and minds and for me it would be a tragedy to limit someone’s personal experience and interpretation with a few clumsy words.

I’ll say this: in our films I’ve always been grappling in some way with the relationship between man and God, trying to find new ways of framing truths that we all can recognize but struggle to comprehend. I made some really bad films when I was a teenager, but what’s funny is that even back then I was trying to deal with these questions. Most kids were partying and I was tormenting myself with questions of pre-destination and free will. What a fun guy I was.

My perspective is always that God IS love. When people feel spirituality in our films, they’re likely feeling that perspective coming through, but colliding with the very real existence of pain. My hope is that the films can, in some way, be healing for the pain and a conduit for that love.

GS: What are some of the most valuable or revelatory lessons regarding filmmaking that you’ve learned over the years?

JW: I’m not sure either Kiowa or I have had any single “revelatory” moments, but the ongoing “soft” lesson we learn over and over is about persistence and patience. Being a writer, an artist, a musician, or a filmmaker requires immense persistence. It is so easy to get derailed by things like finances, ego, and criticism. And it’s easy to believe that we can get where we want if we’re just talented or brilliant enough. But much of the great work comes from people who just keep going after years and years of adversity.

GS: Whether it’s the seed of an idea or a burgeoning script or something else, I suspect you have a notion of what your next project will be. Can you give us a hint of what this project might entail by way of a single word? Perhaps it can serve as a mantra or synecdoche with which to conclude our exchange.

JW: We’re of course very hush-hush about the next project, but I think it’s cryptic enough to say one word, which is “generational.”

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, such as editorial services, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

Jamin Winans is an American filmmaker, writer, editor, and composer behind the films Myth of Man (2025), Childhood 2.0 (documentary, 2021), The Frame (2014), Uncle Jack (2010), Ink (2009), 11:59 (2005), and Spin (2005). Learn more here.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. After a decade, he has recently finished working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.