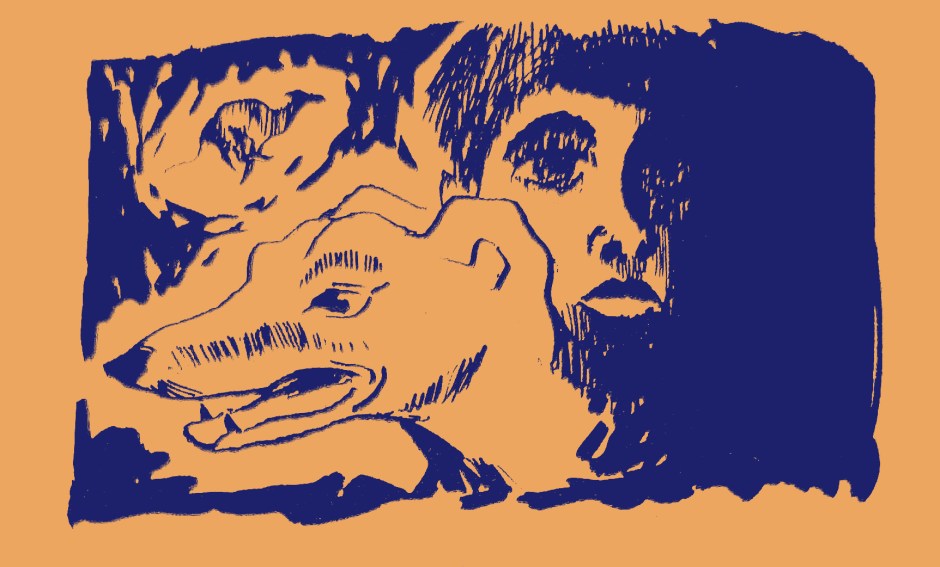

Editor’s note: The following story by Dow Mossman was originally published in Le Beau Petard: An anthology of prose and poetry from the younger writers of the Iowa Workshops (1966), which Dow also edited. The story is, by definition, juvenilia, and yet it offers a special glimpse into the estival and oneiric world that would inform his magnum opus, The Stones of Summer (1972). This early piece is a germinating prelude for the unfamiliar and a lovely recovered memory for devotees. I thank Dow for allowing me to reprint it.

The minute-winning days, like flies, buzz home to death, and every moment is a window on all time…and he came to know the guttering candle-end of time.

– Thomas Wolfe

At dusk they would find their way home—home from the heat and the shadow of the black, crumbling banks of the river, home from the woods and the softly undulating hills. Slowly the packs of Reds and Blacks, Brittles and Grays would wander up the lane where the six black walnut trees hung like darkly quiet balloons in the last dust of the day. The last dust of summer rose in dying swirls beneath their step as they moved in a lane, to a gate, where he had waited for them: waited as he always had: Movement.

“Sis, here girl—Sassy, a’ you a sassy sissy—aren’t you, here sis, atta girl,” he would say as they would jump, putting the paw almost to his shoulder.

“Red, you ol’ winner, o’ mean again today—whatsamatter fellow—mean and cranky jus like me—too old, Red atta boy.”

The younger ones paid little attention as they hurried to their pans: the old ones would not eat until after dark—after he had left them.

When August came, they would leave and move toward the farm. It was always late in the day, and they would pick the boy’s father up at his office and drive west for hours with the sun dying like the inside of a melon unseen before them.

The boy would grow restless and his mother would feed him crackers and pop and tell him that they could not possibly stop again at a gas station because her parents were growing older and they must reach the farm before ten.

The car would grow quiet and the boy would ask of the greyhounds, and why his grandfather did not raise corn like the rest of the farmers. His father would take the old cigar from his mouth and say: “Yes sir ‘ol boy, greyhounds are the best crop that can be taken from Iowa—yes, sir ‘ol boy.” And the car would grow quiet as they rode past the endless fields of corn, and through the still towns beginning now to lie down in darkness:

“What’s this town?” the boy would say.

“State Center,” his father answered.

“Well how come it’s so small, you’d think if its the center of the state ‘id have more people than this.”

“In Iowa the people like to live on the edges,” his father answered.

And the boy grew restless with leaving his home. It was August and in a short month that seemed less than a day, he would have to return to school for the third time.

And he began thinking of home and of playing ‘kick the can’ and of Ronnie Brown who stole stick matches from the supermarket and who smoked old butts and stole money from his father’s pants and who had finally shot that damn Caddy Byers in the ass with his new Sears and Roebuck B-B gun which his father had given him for good grades exactly two days before he was expelled from school. Ronnie Brown had been expelled from grade school; but what amazed the boy was the fact that Ronnie Brown had continued his swagger all summer as if he did not care whether or not they ever let him back in. The teacher had chased him all over the room until she had become so frustrated that she threw her paddle at him and broke a window: he had told her to fuck herself.

Recalling the dark word the boy thought of dark labyrinths. “Com’ on Ronnie, you can tell me whatsit mean, whatsit mean,” the boy had said as they threw stolen stick matches from the old vine-covered wall behind Duncee’s mansion.

“I don’t know,” Ronnie said with a tone implying that of course he really did know, but that for reasons known only to himself he wasn’t talking about it. “I don’t know, but Roger O’Casey says it all the time, and he’s only 13, and I gottem to tell it to me.”

“Well, it doesn’t seem they can kick ya’ out of school if you don’t know what it means.”

“Roger O’Casy said they can, I asked ‘im,” Ronnie said.

Finally the boy offered, “I’m going to the farm tomorrow.”

“Big deal—milk some fat ‘ol cows, and stand around and look at some stupid chickens all day—big deal, why doncha just get some hicky book with pictures?” Ronnie said.

“You wanna go?”

“Your mother wouldn’t even let me on her sidewalk, how’s she goin’ let me in her car?”

“I’ll ask her anyway.”

“You wanna be a dumb shit I don’t care.”

He found her upstairs packing, she was singing softly to herself, putting his clothes in her suitcase.

“What!” she said. “Have you gone mad. I should say not really! Where is he, you’re not even supposed to talk with him—is he outside?” she asked as she went to the window

and looked out from behind the curtains.

“I see you behind that tree, Ronnie Brown,” she said, “GO DIRECTLY HOME, if you please.”

“It’s a free sidewalk lady,” he called up to her, “you’ve got no right. Public, I got as much right as George Washington himself. Whodaya think you are anyway?”

“Mr. Brown, leave or I will come down there and spank you within one inch of your dubious life.”

“My red ass, you will, by Christ I’d call a cop and have you put in jail.”

She was repressing a scream by now, and the boy began to see she was going to cry again. She was always crying.

“How come he always wins?” the boy asked.

“Leave me,” she said.

But she had forgiven him, and they were now going to the kennels, as she called them, and now she was wiping the hair away from his face and he began wondering what she was really like. She seemed to be two things at once to him; she was both soft and hard, fierce and quiet.

“Lemme time ya again, gotta go sixty miles an hour—one every minute; gemme your watch.”

“You’ve done that 50 times, Dow,” she said.

“Lemme once more, only once,” he said.

He took his father’s watch: it was a pocket watch and it was very old and worn. His father’s grandfather had given it to him when he died, and his father had said that the boy could have it when he died, but the boy had always said he wanted a wristwatch, and that he didn’t think much of old pocket watches anyway.

His father was that way though; he always wore a vest even though no one else in town did. This always made the boy’s mother irritated, and she would say: “Simpson, when are you going to get a new suit? Good Lord, look at those pants, they fit like bags—O well,” she would say. “I guess I’m just overly clothes-conscious, but then my whole family is, why when granddad’s dogs were doing well at the track, he would spend $200 for a suit—and this was even in the 30’s; even Uncle Dow dressed that way in high school.”

“One minute,” the boy cried out, “exactly one minute,” not listening to his mother’s chatter. “Did we go a mile exactly?”

“Pretty close, ‘ol boy,” his father murmured.

“Not exactly! Do it again, just right.”

“Simpson!” she said, “Why don’t you tell him it’s a mile and let it go—it’s so like you.”

It was late when they would approach the town that was dying—like a mass of broken pots—against the hills. They would reach the lone gravel road and turn off the concrete highway beginning to cool in the evening. They would clatter over the railroad tracks, and cross the bridge over the thin, dying mudhole they called the Bovine River. But it wasn’t much of a river, and the boy thought of how he could hop over the whole thing on one foot. Around the thin, brown trickle the banks heaved and caved in: there were always bits of trash—old papers, cast away cans and wire, and even an old bathtub or two—covering the banks like a symphony in chaos which nobody could explain. The boy wondered why there was so much junk, and his father had said it was because the people had given up and didn’t care anymore.

“How come it’s Dow City, like me?” the boy asked his mother.

“Great-grandfather Dow came to this valley before the Civil War, and he helped settle it, and they named the town after him.”

“Not much of a city. How many people they got in this town anyway?”

“Only 300 now,” she said softly. “It wasn’t always this way; in the day of the small town there were many fine people living here. I can still see old Judge Judd reading on his porch on a summer night. Then the roads came and people moved to Denison and farther on….”

“Tell him about the time you won the Crawford County foot races—the music contest perhaps?” his father said.

“O, be quiet Daddy,” she said. “Once we owned all this, and then the mansion on the hill, then finally only the hotel and then it was gone too.”

“What happened?” the boy asked suddenly, interested.

“Uncle Clarence mostly,” she said, “he had traveled a lot, and he had been in Mexico in the 1880’s, and he had talked grandfather into mortgaging the land to buy a copper mine there and—”

“There wasn’t any copper, not even enough to make a sword to fall on,” his father interrupted.

“Yes and we lost all of it,” she said. “Mother didn’t even have a penny. You would have owned 1/4 of this whole valley, Dow, because the Dows are all dying out.”

“That why you named me Dow?”

“I don’t know.”

“It’s called splendid decadence,” he said, “It’s based on the idea that a lost town is better than no town at all. Maybe even better than having the town in the first place. So if you don’t have the town, you at least have the children named after the town. So if you have the children then in a sense you have the town and especially the heritage of the town. It’s an American idea,” he said. “Besides there’s the more practical fact that your mother did most of the work. She insisted. That’s an American idea, too.”

“They call me Dowy-Cowy.”

“That is a shame. My mother was the same way. I guess we just come from a long line of eccentric mothers. Simpson, great Jesus, what a name.”

“Dow is a nice name for a boy,” she said. “My brother never minded it.”

“I think it stinks. Ronnie Brown says the only answer is to start kicken’ a few girls where it hurts the most.”

“He would say something like that,” she said softly, looking out the window toward the town.

And then he heard the hounds. Their cry was warm: it began as one and increased to many as the car pulled up the lane of the six black walnut trees, and as more dogs began to slowly crawl from their clean, white huts which lay in long, even rows like an endless string of dollhouses. The lane ran under the hill, and there were two houses upon the hill—the large stucco ranch style house where the boy’s grandfather lived among his trophies, and the tall, gray, wood house where Elmer Stout lived with his sprawling family. The boy looked, and he began to hear: in the long rows of pens stretching out over the fields he could hear the dogs stirring, and he could see the hill and the fields touched once by the spreading moon of late summer. Down the hill his grandfather came with strong, even strides. He was 57, and he was the kind of man who somehow—somehow inexplicably and intrinsically—wore the Fact of time and the flowing presence of his time upon his very being. His sharp nose and his darkly powerful eyes made his presence hawkish: physical; immediate; even guttural in the sense that guttural means hot and vital. His well-made hands were constantly flicking the sides of his face, palm in and then palm turned over and outward; under the nose, against the wired afternoon growth of his face, and then finally the hands would drop downward to his sides—the cycle to be repeated again minutes later against the lined and tanned continent of his face. “Dark, Dark. The dark face darkly calls, and what is the weather in my grandfather’s beard.” The boy had thought this of him then seeing him in the way you would see a shadow on the hot brick walls of the late afternoon. Oldham was young, young even then in the sense that the years which had never touched his face—the years which had left his young wife old—had also never touched his soul or whatever it is that is to be finally found within a man. He had usually been mistaken for his daughter’s brother: and he had walked his dogs up to ten miles a day much the same way an early Christian ascetic would have sat on those ageless pillars of brick. Time waited on Arthur Oldham and Arthur Oldham waited on no man. The night grew quiet…

At the turn of the century, on the brown and endless plains of Nebraska, the dogs were run every weekend. Art Oldham was just out of high school where he had managed to learn greyhound bloodlines, dating back to the 12th century and written on labyrinths of paper, instead of arithmetic. He became cramped clerking in the dim midwestern store—the store selling everything still in an age not yet specialized, selling ice cream and blankets and even horse harnesses in a time only just then bending slightly to the brink of Mr. Ford’s machine—and he played semi-pro baseball in an age when Casey-was-still-at-the-bat, an age where the still-skirted women yelled for glory and mayhem on those otherwise quiet Sunday afternoons. And they yelled for him. But feeling constrained by the borders of the town and even by the limitless retching heave of the broad prairies, he felt the need to journey out. It was after all also the age of Rockefeller and Vanderbilt, a time not so removed from even Fisk and Gould. A time when any man could make a million. And all the people in the bright bleachers loved him, and he knew; loved the way his well-made hands flicked the sides of his face as his dark eyes flashed and the deep continent of his face grew even more intense. —“Yes sir it’s sure nice to have that old Art around, he’s quite a sonofabitch that Art is,” they would always say.

It was like that when Art met Doc Mahoney at a National Coursing Meet. Gnarled and tubercular the Doctor drank and raced the dogs on those now ghost-grayed fields where the rising whine of the struggle remains ethereal in the bright afternoon. But the Doctor finally drank more than he raced and the boy Arthur began more and more to control the kennels until it was finally not even unusual when he said: “Doc, lemme have that old dam Meadowlane, I found this sire I want to try with her.” —“Ya sure Art” he had said, “sure Art but she’s too blind to be any good.”

Only she was good, and she produced Traffic Officer who although he was only a dog, was as good in his field as Babe Ruth, or Shakespeare, or Michelangelo, or maybe just Man-of- War. “Yes,” Art would say years later to the boy when on those rare occasions he would consent to come on to the porch and watch the evening lie down on the field, “Yes, she and about half her offspring were blinded in the right eye but Jesus how they could run. Run run, my God, they could run, but that was only a small part of it.” And then he would hesitate and then finally walk slowly down toward the first corner pen where only the young and the finest were kept, and he would say: “Yes and they were big too. Some of the biggest dogs in the country. Of course they’re all big now and the breed has got about twenty pounds bigger in the last thirty years but my dogs were the first to get big, and O Jesus how they could hip in the turn. I can still, see the time in Boston in the early thirties when Court Jester ran right over three dogs in the last turn to win the season’s Stake Race. He was about the biggest and fastest dog I ever saw. Run, my God, he could run. He’d just swishem away like he was fanning his tail at flies.”

And the quiet tide of his life continued uncut: all conflict was subtly reduced to the Fact of the dogs. Some men were simply ill-bred, without beauty, without intelligence, without even wit they were, he saw, rightly reduced to life in the end kennel. It was an animalistic philosophy, but there was order and strength in it and he held to it quietly and without bigotry until he himself was larger than the force around him. And he was, or at least became, force itself. And that was all for the flow of image around him formed him within a simple movement, and within a circle of experience in which he moved with such ease that he created no ripple of disturbance. And he finally became simply force in movement himself. Movement.

And the calmness underlying the force of his existence remained unbroken until 1936 when the boy’s uncle, who was also named Dow after the town now dead in the hills, returned from the Olympics and when Oldham had sat in the dugout of the Boston Red Sox watching his offspring try out for the Major Leagues. He sat watching quietly until he heard a coach say: “What’s that kid’s name at short?” And then: “Oldham, Dow Oldham” was the vague reply and then: “My God has that kid got lead in his arm, he throws it like it was a fat, wet duck. Never make it to C ball if he had a broom to take him.” And then the other: “Ya well he hits like he’s got that damn broom.” —And the boy had finally heard this story from his mother after he had completely tired her with his stories about how he was going to play with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and although she had not been living with her father for ten years she had said with the fear of a startled cat: “And whatever you do don’t tell granddad I told you.” And then she gave him a quarter and he went to the store with Ronnie Brown.

Now fifteen years later, Arthur Oldham walked down the long path from the hill where his grandson stood fearing him as he always had. But the boy had sat in that new green ‘51 Chevy constantly slapping the white ball into the clean smell of linseed oil, and he had rarely returned from those quiet schoolyards before the dark cold shadows of early spring had completely rilled up upon the slack brick walls of the building named for some obscure American president he had never heard of except in a dull and unlife-like way. And years later he would hear the words of the poet which said to him: The ball I once bounced in the schoolhouse yard: has not yet reached the ground. And he would believe it, but now the boy looked into the dark hawk-face of the grandfather who had just come from the hill and he saw the hands flick the sides of the face and the eyes looked down at him offering nothing but a final and irrevocable judgment. The boy showed signs of being good—but not great.

“How was the drive,” he said, kissing the boy’s mother, warmly and yet somehow with more ceremony than feeling, and then finally shaking the father’s hand. “Did you bring your glove?” he said looking down toward the boy. “We’ll try to get that lead out of your arm this year again,” he said.

There was always the fear, and the boy was glad to be able to get inside and in bed away from his grandfather. Late, the katydids would raise their warm call from the grass of the fields: the dogs seemed to join in and a steady crescendo seemed to raise to a howl that made the boy feel of his existence—he grew safe in it: the train going toward Omaha would rise and fall in the night sometimes fusing in the sound of the night like a lone bitch moving away in the hills: the land was best when a storm would come, and the wind and the small rain would blow through the single willow bent like a wet and heavy curtain upon the hill. Then in the wind the boy’s grandfather would pass like a mute and stupid Lear through the den where the boy was sleeping with the trophies which clustered the walls like so many scattered, but well-kept, tombstones. Then into the wind of the porch the man would stand and look down the long rows of pens half buried in the half-light, simply standing in the heated retching of the face of the storm. And then the boy would hear the sudden voice of the grandmother come from the dark bedroom saying: “Art, Art, get him down to the storm cellar, down to the storm cellar.” —“It is all right, Gen, go back to sleep, it’s not even a storm yet.” And then he half-consciously remembered the chaotic heaves of the storm grow more quiet….

“Get up. Get the hell out of that bed, you’re not going to be laying there all day”, and his grandfather stood and seemed to glare at him. “Ja-eesus are you lazy: Get out and get doing.”

“Leave that boy alone, Art,” his grandmother said from the kitchen, “He’s not a hired man, it’s only 8 o’clock, what is the matter with you—he’s not going out to plow, besides the grass is wet.”

“Awww, God, Gen,” he said as he walked away. “He can’t spend his whole life in bed.”

Later, after his grandfather had left for the fields, he would arise. The days seemed to hang in the air as if they would follow each other in a string that would never end—or had they even begun. Time did not exist as he wandered with his shoes untied, and his limp sweatshirt hanging loosely about his knees. He wandered through the pens where the dogs lay in the cool shade of the walnut trees with their dull red tongues draped languidly about their parting jaws. It was hot and he loved the dogs. The day continued toward night.

“You might as well come and watch them Course,” he had reluctantly said as they sat at lunch. His grandmother had made him say it: he did not want the boy along. Later, as they walked in the lane, the boy stepped in a fresh pile of cow manure lying half-lost in the dust.

“God, are you clumsy,” the man had said.

The boy remained silent and began to fall farther behind.

The field was flat and green. It stretched out between the four fences for two hundred yards, and at one end there was a blind constructed with drying corn stocks into which the jacks could escape as they were chased down the field. The man would light a cigarette and say: “Bring in the first two dogs, Elmer—Lady Mary there and The Big Policeman.”

They would come on the field leashed: their thick, throaty cries rose as they strained against the leather straps holding them back. Their lean, well-bred muscles strained and their eyes grew slightly wild as their pointed heads twisted in all directions. The evolution of their bodies was meant for one purpose and they grew tense. The jack was plucked from his cage and shoved under the noses of the two dogs. They snapped and pulled violently at their leashes—the rabbit began to freeze and yet he somehow twitched spasmodically. When he was released upon the hot earth, the dogs became calm—they began a cold, hard stare toward the jack almost as if they were trying to make him faint from the fear of an inevitable death.

When the rabbit was released, he began a jagged pattern up the field toward the corn. The dogs lifted their furious heads to cry and beg in a slow, soft whimper that broke into a rising howl the instant they were released.

The boy grew fascinated by the scene sprawled in the grass before him: the heat of the earth, and the coolness of the shaded grass contrasted as he became wrapped in the death struggle before him. The two dogs jostled each other madly as they turned sharply with the fear of the rabbit—the man rubbed his tanned, well-kept hands against his chin and said: “Look at her hip. God can she throw a hip. O, by God she’ll be good on that last turn on the track. Lookit that big black bitch hip.” The large, black greyhound began closing ground and the single frantic leans of the jack became longer and higher and more intense. Finally, the rabbit nosed through one of the small holes in the board behind the dying corn, and the dogs frantically wandered up and down the long row of corn; their heads were hung low—they were looking for a scent, a way.

The boy relaxed, and slowly murmured “Jesus.” It was the first time he had ever said it that way, and he felt strange, and yet bold.

For hours the boy sat on the wormwarm boards of the gray, unpainted bench and watched. He was transfixed as the rabbits ran with their ears drawn back tight over their heads making their eyes seem to stand out from their heads. And they always escaped—obviously they always could. Always the small receding blot disappeared at the end of the field and always the boy relaxed. But the chase was never over, it always began again.

Then once late toward dusk one of the dogs won, and then both dogs grew wild as death came home, and the taut, frantic forms tore into the red and innocent guts of the jack: the two dogs began tearing the rabbit in opposite directions, ripping him into pieces that stuck in their mouths and then fell in gray balls of fur to the ground. As the man ran to tear the dogs away, the boy slowly began to walk up the lane where the black walnuts hung like heavy balloons in the red sky. The spreading shade of the trees grew, and the boy thought of darkness; Of darkness and night spreading, of shadows growing not warm but cold, and torn bellies, of night coming cold—and final over a last dying day—and then from the hill he vaguely heard his mother calling:

“Where have you been, honey?”

“Just watchin’ the dogs.”

“Was it fun?”

In August the evenings fell softly: the air leaked warm heat in the night, and the growing shadows of the walnut trees spread over the dogs lying in the long, narrow pens. The air became still and the dust settled in the lane. Alone, after dinner, the boy walked on the rutted lane stopping often to feel the black, heavy gnarled bark of the trees. He began tossing pebbles at the iron posts which ran forever beyond the eye beside the lane like varnished veneers, or like magic flutes dancing the green inversions on the ivory rivers in darkness. Inverted shadows. His eyes tensed as they looked into the last expanding, yet dying, heave of the sun. He turned slowly and looked at the dogs. Old Traffic Court, son of Traffic Light, son of Courtly Albert, son of Prince Albert, son of Court Jester, son of Mary Meadows, daughter of Traffic Officer—with his red jaws graying with age, hesitantly came to the fence, and whimpered as he rubbed his black cold nose against the boy’s hand. And the boy began to see:

Life is warm. Like sheets of night. Black bark. But death is a night, not warm, black bark. Like cold noses, not fur, not warm. Life and warm and fur and dust rising and just before night comes the sun spreads the most all over the sky in red and bleeding blankets. Like bellies.

“Dow, hurry,” she called from the hill, calling him back from the ivory rivers where the green shadows danced the inversions, “we’re going to see Grandma Great, hurry Dow.”

And the dark road ran silent through the night. They were talking, but he wasn’t listening. He could see the faint light of the night as it lay in the hollow ponds of the porch of the ditch. Perhaps his great-great-grandfather Dow was the first one to see this land in the moon of August. Maybe he even crossed this same part of the land on a night in August. Always black the night is August is night is warm in August but night is cold not August not warm. Two things. Warm and cold and August and things are one not two, but she my mother is twice or two at once hard and quiet fierce and soft. Two things. Rabbits. Ronnie Brown and rabbits and hell jesus he’d say is a fuckin rabbit a person. People aren’t rabbits, shitin rabbits he’d say for christ’s sake they aren’t shitin rabbits you dumb shit.

And then suddenly her house was there. It was a small house, and she had raised seven children in one much like it in Nebraska. And she was Grandma Great. Art was the only one who had any money, and he wanted her to be placed in a nursing home. She was Art’s mother. She was too old for anything else, wasn’t she? She was 89 years old, and she said she would die in her own house, with her own bible, with her own memories, in her own way, in her own (and God’s) good time. She had just taken out a five-year subscription to the Saturday Evening Post. She was completely blind now but she would have it read to her and her eyes were soft and looked as if they had clouds in them. She was even nearly blind when she came to Nebraska from the slums of Liverpool as a 17-year-old girl.

And she had married Thomas Oldham who had come from England also, but by a much more classic route. Thomas Oldham was a typical Victorian black sheep: he was on the way of the English Establishment when drink and the fact that he broke the jaw of an English schoolmaster sent him packing to the vast and chaotic provinces of America. He was six foot six while she was not quite five foot and so theirs was a comic and fated marriage in more tangible terms than class. In the small town in Nebraska Thomas fell from grace to the status of traffic cop which is why generations of dogs all seemed to be named after the recurring themes of Traffic and Court.

She was even smaller now, she seemed to shrink more every year, the boy thought, but he also sensed the complete indomitable quality of her will. And she was very present when she would come onto the porch and feel the summer night, seeing the last drying shades of the flowers of summer and hearing the sound of the locust she would say: “Humming the locust die. It is a good way. They make me see England when I was a girl going to the country—England was a wonderful place except for the people. And I’m considerably glad I left,” she would say as her life gathered around her on the receding porch of a dream.

“O, what a line of memories,” she would say as the locust whined their death spiral on the cedar log, “seven generations I have seen, from my own grandfather who was actually born in London in 1824 in the time before even Victoria was barely a girl. Yes and I can almost remember crossing the Atlantic and now we ‘ave Dow here on my porch far from England and I ‘ave seen ‘em all put in the ground, but me, and I guess now it’s my turn,” she would say laughing softly and gripping the worn handle which had one day arrived in Nebraska out of nowhere with the note “Emma is dead” which had been hurriedly scrawled across the paper and signed “Sister Bessie” with the postmark: Liverpool, England.

And she only asked, sincerely and without noise, to not be made a martyr of because of course the simple trauma of her years defied anything less to come. —And then once when they were alone she said to the boy: “You are very young and I’m very old, but part of me is in you and someday you will remember perhaps that I once spoke of setting out—don’t be a fool and live in a small circle of hills, if you will wander out, you will find many hills you have never imagined, many places you have never seen. This is all I hope you get from me. Good or bad any man is all there is, or ever was, like him. Few people ever know this and if you will only know you are you will know.” And her voice trailed off, dying softly like a slender fire, and she rocked on in silence. And he would never know her for twenty more years when he would cast back into, or through, the thick and pale and yellowing Isen-glassed layers of time and he would suddenly and irrevocably come to know the overwhelming prism of his being. But she was dying too. He sensed it: He knew it the way you come to know something without ever stopping to know you know it.

She is dying dying not like bellies though he thought nightdeath are two things like hot guts on the hot earth and like quiet porches. And my mother says not even a sparrow can lie forgotten and Ronnie Brown says you dumb shit are you going to believe that crap you stupid sonofabitch. And the locust whine whine whine on the cedar log whine whine whine, whine-whine-whine and I am alive Iamalive in the hot fields and the torn bellies and the quiet porches.

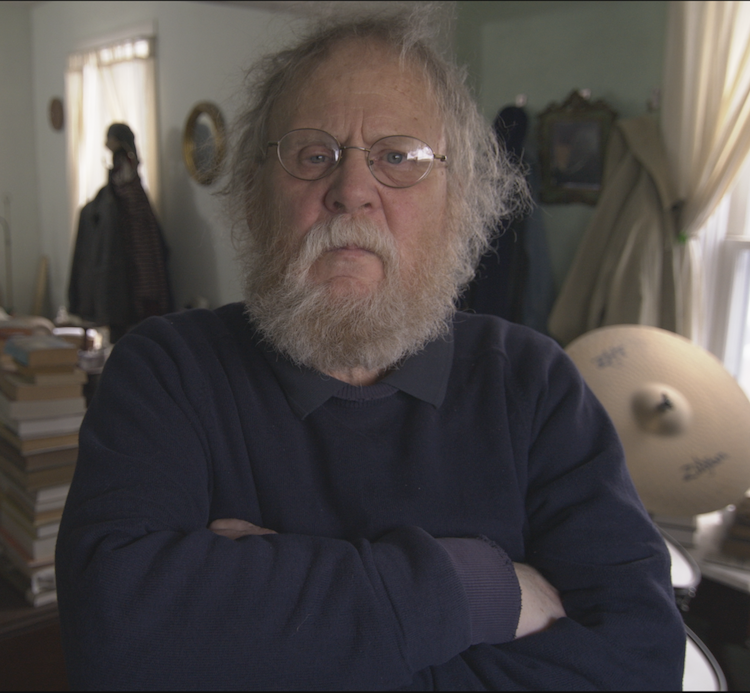

Dow Mossman received his B.A. from Coe College in his hometown of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. In 1969, he earned his MFA from the University of Iowa’s Writers Workshop, only twenty miles away. After winning several awards for his fiction, including a Book-of-the-Month Club Fellowship, Mossman completed The Stones of Summer in 1972. Ten years in the writing, the novel was heralded as the debut of a major new talent, and the book’s style and content were compared by critics to James Joyce, William Faulkner, Malcolm Lowry, and J.D. Salinger.

Mossman then disappeared from the publishing world entirely. As the subject of Mark Moskowitz’s Slamdance award-winning documentary, Stone Reader, The Stones of Summer was rediscovered and republished by Barnes & Noble in 2003. Mossman still lives in Cedar Rapids.