Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia features a scene about poetry translation that has stayed with me since I saw it as a child. The film’s poet, Gorchakov, asks his interpreter, Eugenia, what she is reading.

“Tarkovsky, poems by Arseny Tarkovsky,” she replies.

“In Russian?”

“No, it’s a translation. A pretty good one.”

“Chuck them out.”

“What for? Actually, the person who translated them, he’s an amazing poet in his own right,” Eugenia retorts.

“Poetry can’t be translated. Art in general is untranslatable.”

At first, I took this as a simple truth. Not immediately obvious, but discernible. Whatever art may be, it is singular. I wrote that message in Sharpie on the back of my shoe’s tongue and carried its thesis with me, testing it against the world by holding it up to a branch or a brushstroke, measuring its true length.

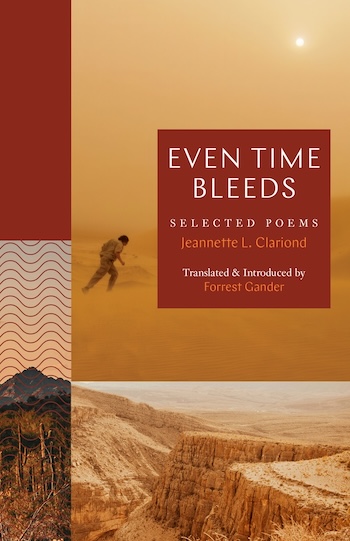

Nonetheless, as a reader, I am grateful for translations. Much of what we read in life depends on them. Moreover, I am also grateful that Jeannette L. Clariond’s first English collection, Even Time Bleeds (Princeton University Press), is a bilingual book that largely retains the original Spanish text on each left-hand page. However, the other side of the book, brought to us by the translator Forrest Gander, a poet of many accolades in his own right, has left me with the impression that essential aspects of Clariond’s poetics remain in Spanish only. Yet, what is here from Clariond outshines any attempt at translation and has turned me into a proud new champion of her work.

I first noticed a tonal shift with the innocuous, at first glance, change of the book’s title, taken from the final line of the first poem in the collection, “Post Canto.” El tiempo también sangra (literally: time also bleeds) has been changed to Even time bleeds. A strange choice, but of seemingly no consequence to the meaning.

Issues such as these are expected for various reasons, and that is mentioned in the translator’s note. He offers the example: Teñida de luna, la madre: mundo inventado para aliviar lo que aún no es, which he translates literally to: Moon-tinted, the mother: world invented to relieve what is not yet / what does not exist. Gander says, “Such metonymic compaction can be problematic for the English-language reader,” and wants to offer “guidance” to help wade through the many implications of the original Spanish, such as the mother (as in world-mother) vs my mother, or the “Heideggerian-sounding what is not yet.” So he changes it to read: “Moonstruck, my mother: a world needed to be invented to allay what wouldn’t come to be.” This is perhaps well and good for this single line, yet doing this sort of pre-chewing for the English-speaking readers leaves quite a bit of the poetical ambiguity on the table, flattening a much more surreal and associative poem.

I am not disagreeing with Gander’s interpretation of the main narrative arc of this poem so much as I am suggesting that the original Spanish contains more worlds of reference and meaning than Gander’s translation gives them, or the reader, credit for. For example, I find many poetic phrases replaced wholesale with literal interpretations. Espuma en lo abierto (foam in the open air) has been changed to “an ocean breeze.” Ciega parcela su lengua (blind parcel his/their tongue) has been changed to “what she didn’t see is what kept her quiet.”This is particularly theme-breaking, as the symbol lengua shows up in a later line of the same poem: “The world is a huge tongue unfurling itself down the street.”

There are instances of simple words being replaced with specific and even jarring alternatives. Instead of hearing (Que me hablan de aquella luna), we smell(“redolent somehow / of the moon’s light”). Instead of “there concentrates the dispersed” (allí concentra lo disperso), we get “dross condenses.” And instead of “the word finds its destination” (la palabra encuentra su destino), we get “the word determines the dole,” which rings political and feels off from the rest of the language in the poems. Yet not all changes make the simple and oftentimes more elastic phrasing into flatter, more specific terms. At times, the original words are translated into more simplistic approximations. For example, verdor, which has a direct English equivalent in “verdure” that would retain its vegetative implication, has been turned into the more science-fiction sounding “green world” or, in a later poem, only “green” despite that poem invoking foliage.

And this is the heart of the issues with the translation: it puts the text at odds with itself in random and unproductive ways. A line that reads“the color of the ink” (el color de su tinta)has been changed to “her handwriting,” even though it follows a line ending on “void” and precedes a section that speaks of shadows, both of which are evoked in the color of ink. This tends to trample on Clariond’s sophisticated use of symbolic language, which is persistent throughout her poems. In fact, in a later poem, titled “Ink,” we find a stanza that makes a clear distinction between “writing” and “ink”:

Writing is

invisible. Whatever

you see on the page

is no more than ink,

A sun-bleached

spine.

Less than perfection is not, in and of itself, a very fair critique of anything, much less the impossible task of poetry translation. However, given the nature of the poetry we are talking about, its quality and rarity, the stakes are high. The language that Gander questions, “What does the Heideggerian-sounding what is not yet imply?” is, in fact, announcing itself as an epistemological text. Which is why all the changes become so baffling in retrospect. There are constantly shifting ideas about power, not in the narrow politics that seem to be laid out for us, but in the deeper ontological ideas about what the world is and the despotism of our own interpretations of it. When Clariond says things like “intolerable the world, if could not be thought,” or “habituated to light, we forget how to read shadows,” these lines perk the ears of anyone sensitive to Hegelian negation. Further, she says, “without a passion for emptiness and Nothingness, the poem fails to register the real,” or even the Borgesian, “there are words whose fate is never to be uttered.” In many ways, these examples show just how difficult the Gander task was, while also revealing the breadth of Clariond.

From short Koan-esque one-liners to personal poems about her mother and a dizzying symbolic streak that verges on surrealism, Clariond’s poetry exists in many spaces at once. Gander has grouped the piece into sections of poems from complete books, with selections of lines from “Ammonites” placed in between for breath and pace. This structure mostly works, yet leaves the reader a bit starved for more. I would be happier to have complete works from Clariond so that I can read them fully, organized inside their original context. I will remedy that soon, as she has at least three other books that have been translated and published under the radar. That is not to say I don’t love a random smattering of poems across different styles and subjects, yet the roughly seventy-something pages the book comes out to, after dividing it in half due to its left-to-right bilingual nature, are simply not enough. I walk along the side of this barn and peer through missing slats. Some images arrest. Others refuse to resolve. And though I go forward and back again, I cannot change the angle of my view. More boards need to be pulled back before the picture is whole.

If one has not yet read Paul Celan’s “Todesfuge,” I implore you to do so right away, as it is a stopper of a poem. It will freeze a piece of you in the sky alongside its graves until that black milk takes you with it. Clariond has personal feelings about Celan as well, and here her writing proliferates with sound. Where she deals sometimes in symbolism, sometimes in epistemology, and now and then that personal lyric, here, stooping in front of Anselm Kiefer’s Sulamith, she grieves it all. Here is an extended quote from the poem “Ekphrasis” to give you an idea of her range of thought and feelings:

When the incision reopens the wound, who will set beside

your face

the blood soaked chalices, who will cloak with imperial purple

the casket in which I see you on your way to the next dawn?Someone will haul the bodies. I’ll lean from the window

and my sobbing will ricochet through the mist

like some memento lost in a cluster of tulips.[…]

What escapes the mouths of others

looks to me like long filaments radiating

from a flame-encircled rose.Translating you, I live ever closer to the fissure.

And I too go on digging the pit. Taking up the word, I dig

and keep digging down through the dust of bones,

to an absent space lipped with ash.

Her words are crisp, like a good broth, thick with gelatin but clear enough to see through to its subject. At times, I tend to appreciate other writers whose words slide around inside the mouth cloyingly like butter. However, here the lushness is the culmination of the layered flavors, so deeply entwined that one simply calls it good and continues drinking. Wir trinken und trinken. In my own grief, trying to find, as Clariond does, the difference between the artist-manipulator and the despotic strongman, I know we will one day compare translation notes in that same inky abyss.

Brenden O’Dell lives in Northwest Portland, OR with his spousal equivalent and cat. When not working on his novel he can be found playing jazz keys in the window of his apartment. More of his work can be found in the Wake Review and Rubbertop Review.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.