In the March 1918 number of the literary journal Nord-Sud, the journal’s editor, poet Pierre Reverdy, published a striking definition of the poetic image:

The image is a pure creation of the mind.

It cannot be born from a comparison but from a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities.

The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be—the greater its emotional power and poetic reality…

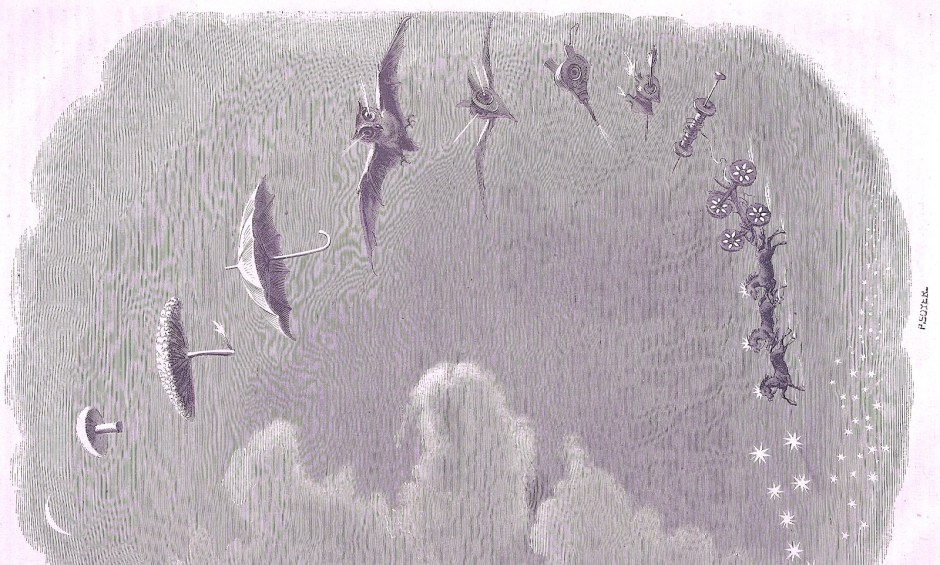

What Reverdy is suggesting here is that the poetic image arises from a kind of sleight of mind in which phenomena, real or imagined, from distant realms are brought together and made to illuminate each other, with the greatest illumination being produced when the ontological distance between the phenomena is the largest.

Reverdy’s definition of the image was soon after appropriated by Surrealism’s founder and main theorist André Breton, who quoted it in the first Manifesto of Surrealism. Breton added an important codicil: that the bringing together of distant realities has to occur as an impulse arising from the unconscious. He asserted that

If one accepts, as I do, Reverdy’s definition it does not seem possible to bring together, voluntarily, what he calls “two distant realities.” The juxtaposition is made or not made, and that is the long and the short of it. Personally, I absolutely refuse to believe that, in Reverdy’s work, [such] images…reveal the slightest degree of premeditation. In my opinion, it is erroneous to claim that “the mind has grasped the relationship” of two realities in the presence of each other…it has seized nothing consciously. It is, as it were, from the fortuitous juxtaposition of the two terms that a particular light has sprung, the light of the image, to which we are infinitely sensitive. (Manifestoes, pp. 36-37)

The image, in other words, consists in a spontaneously arising conjunction of ordinarily unrelated phenomena which catalyzes a thought-provoking “spark” whose emergence is “a function of the difference of potential between the two conductors,” which is to say, between the incongruously juxtaposed realities (Manifestoes, p. 37). From such an incongruity would come an emotional shock and with it, an intuitive insight. This is the cardinal principle of Surrealist poetry, from which it never deviated.

***

Nearly twenty years before the 1924 appearance of Breton’s first Manifesto, Freud in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious analyzed a certain kind of joke that consists of substituting a word that means one thing for a similar, sound-alike word that means something entirely different. The comic force of the joke is the product of the incongruity of the substitute word’s referent occurring in a context in which the referent of the substituted word would be expected. Such a joke, like Breton’s catalytic image, produces its effect by bringing together unrelated thoughts.

For Freud, this kind of joke employs a technique that allows the joker to

focus…our psychical attitude upon the sound of the word instead of upon its meaning—in making the (acoustic) word-presentation itself take the place of its significance as given by its relation to thing-presentations.

In the footnote to this passage, which quotes from Section VII of Freud’s 1915 paper “The Unconscious,” Freud explains that “the conscious presentation of the object can be split up into the presentation of the word and the presentation of the thing” (Jokes, p. 146). In cases like the joking or punning substitution of one word for another, the substituted word’s thing-presentation, or referential function—its picking out a given thing or idea—is shunted aside and nullified by certain of its non-referential qualities, for example its sound, its shape, rhythm, and so on, which link it to the substituting word, whose own referential function picks out a thing or idea more or less divergent from the one picked out by the word it replaces. This substitution collapses the difference between the two words and fuses, under the auspices of the substituting word, the more or less distant realities represented by each word’s thing-presentation. Such a fusion catalyzes a comic reaction in the hearer.

Freud’s word-association joke is entirely a function of language. It’s made possible by the dual nature of the word as, on the one hand, a material, sensual quasi-object consisting of sound and shape, and on the other hand, a sign referring to an object or idea, and realizes itself by separating these two dimensions and playing the one off the other. The humor that results is the humor of setting language against itself and making it say something it isn’t authorized to say. In essence, the word-association joke subverts the reality principle by affording a variety of enjoyment that Freud characterized as a “pleasure in nonsense,” which we get when we “jumble up things that are different rather than…contrast them” as we ordinarily would when faced with unlike object-presentations. Freud traced this pleasure back to the games played by children as they learn to use language, games in which they amuse themselves by creating sentences whose absurd meanings are the products of words chosen for their sounds rather than their senses. As children mature, they’re gradually encouraged to relinquish these games and to use language in the service of “efficient intellectual functioning” only. And yet such verbal “nonsense” retains its capacity to produce enjoyment even in the adult, for whom it represents a tension-easing “rebellion against the compulsion of logic and reality.” Jokes trading on this technique of “inappropriate” word-substitution, Freud claimed, produce a psychic relief by way of shedding the “burden of intellectual upbringing” (Jokes, pp. 152-156). They represent, in other words, a pleasurable regression to childhood and childishness.

***

Although the catalytic image and the word-association joke share a common mechanism—they both disrupt ordinary modes of thought by bringing together otherwise incompatible realities—they differ in their details. For Freud’s word-association joke, the mechanism is entirely internal to language. What the joke plays off of is the dual nature of the word, the difference between its material, sensual qualities—its word-presentation—and its referential content, or thing-presentation. The joke exploits this difference, contained within the structure of the word, by subordinating the latter to the former and forging its association to another word on that basis alone. The upshot of this is that the working dynamic of the joke—the associative mechanism through which it realizes itself—plays itself out within language and through language. The catalytic image works at least in part by exploiting this same difference. In those instances where it does, the linkages through which it brings together its distant realities are formed on the basis of its constituent words’ qualities of sound, rhythm, shape, and perhaps even the physical sensations accompanying their articulation.

At the same time, though, we must remember that the catalytic image is an image, which is to say the presentation, in verbal form, of some thing or idea. For the catalytic image generates its force—creates its spark—by juxtaposing realities. This brings the word’s thing-presentation back into the picture, albeit in a manner determined by a poetic rather than an everyday logic. I believe this is an important point. Further, that these realities are implicitly understood to be real—actually or, in the case of purely imaginary notions, potentially—is borne out by the presumption that their convergence would not occur within the real world, given all of the constraints that define it. Their license to coexist is granted rather by what Breton called their secret affinities—kinships that don’t show themselves to the naked eye, as it were. This is because, as he explained it later in “Ascending Sign,” they are revealed to an analogical way of thinking, an almost archaic mode of apprehending the world and its relationships which involves seeing correspondences between things that supersede their ordinary logical or causal relationships. Breton’s particular form of analogical thinking bases itself on envisioning one thing in terms of another on the basis of a partial or covert resemblance, a resemblance that ultimately crystallizes out of the associations its envisioner finds or draws. These analogies point beyond language because they concern, and overturn, relationships between things in the world, relationships that they presuppose in order to oppose. As Breton said in “Ascending Sign,”

For me the only manifest truth in the world is governed by the spontaneous, clairvoyant, insolent connection established under certain conditions between two things whose conjunction would not be permitted by common sense…. (“Sign,” p. 104)

***

Freud’s word-association jokes are for the most part trivial—puns and the kind of word games that by nature tend to produce what he calls “little wit and much enjoyment” (Jokes, p. 155). These put us in territory far removed from that shaped by the profound imaginative effects promised by the catalytic image. Nevertheless, I think the two qualities he finds in the word-association joke—rebellion and pleasure—can be found fused in the catalytic image as well. If the word-association joke produces a pleasure in the way it subverts the logic of everyday language use, so too at some level does the catalytic image. There is a subtly humorous element in it, even when no humorous effect is intended. There is just something funny—call it metaphysically funny—in analogizing objects or ideas from ordinarily ontologically distant realms, something humorous in transvaluing the value of ordinary thought in this way and in thus cocking a snook at it. Its hegemony over the imagination is shown not to be absolute or even particularly compelling. Merely by existing, the catalytic image takes it down a notch and mocks its pretensions to dominating thought in the way that, say, Groucho Marx’s verbal absurdities mock the pretensions of the upper-crust figures unfortunate enough to cross his path. Freud’s remarks on the humor of incongruity allow us to see in the catalytic image this often overlooked and unappreciated quality. And it’s interesting to note in this context that during its early period of experimentation with sleep-writing, Surrealism saw the kind of word-association humor Freud discussed in Jokes in the form of what Breton described as “word games.” These largely consisted of Robert Desnos’ purported channeling of the spoonerisms and puns of Marcel Duchamp’s alter ego Rrose Sélavy.

But in the end pleasure, even a rebellious pleasure, although inherently present in the catalytic image, isn’t enough to explain its force and exhaust its meaning.

***

It seems to me that the image, as Reverdy and Breton describe it, contains a meaning that plays out on two related but distinguishable levels: the existential-revelatory, and the poetic-creative. To the extent that it draws upon and articulates associations embedded in what I’ve elsewhere described as the writer’s semantic underworld—the affective, sensual, and other “subjective” associations that words carry for us, associations that augment and overflow words’ conventional and commonly understood content—the catalytic image expresses meanings and affects revelatory of the writer’s existential engagement with his or her world. Surrealism’s early experiments with automatic writing were meant to unveil, through the resulting unconstrained imagery, the workings of the mind; in effect, the movement’s assumption that language, when wielded that way, could manifest material from the writer’s innermost reality, presupposed a view of language as potentially existential-revelatory, even if they wouldn’t have used the term “existential” to describe the nature of the psychic material they hoped to uncover. In effect, what the catalytic image was thought to spark was a kind of knowledge or insight in which a world—the world as the writer inhabits and interprets it, as revealed in what Breton in “Ascending Sign” called the “infinitely rich…network of relations” such images express—manifests itself.

If at the existential-revelatory level the image is descriptive, at the poetic-imaginative level it becomes something prescriptive. There, the catalytic image as Breton and Surrealism conceived it wasn’t held to reveal an existent world so much as to poetically project the possibility of a new world by imaginatively reordering relations among things and ideas and establishing connections which common sense would prohibit. The image, by bringing together distant realities through an unlikely analogy, would reshuffle the world’s deck of ontological cards by imaginatively overriding the being of the real with the nothingness of a real that is not, but possibly could be. Such a negation may represent a pleasurable rebellion against the resistance of the real, but for Breton it was something more serious than that. He claimed that the conjunction of distant realities that the analogical image expresses “creates a vital tension straining toward health, pleasure, tranquillity, thankfulness, respect for customs” (“Sign,” p. 107). (This last item seems strange coming from someone who always expressed disdain for conventional social relations, but what he likely meant by “customs” was something like esoteric traditionalism, which was a growing interest for him at the time of writing.) In short, through the analogical relations it expresses poetically, the catalytic image intervenes in the world by bracketing the logical rules and relationships ordinary reality imposes on things, negates them and substitutes instead an imaginative ontology powered by correspondence, condensation, and transmutation. It prescribes, if not a new world, then a new way of being in the old one. Breton summed this up concisely when he bluntly declared to interviewer René Bélance that the role of poetry is “to emerge—come what may—as a force of emancipation and divination” (Conversations, p. 191, emphasis in the original). Even Desnos’ clever word-play was taken to be a “wholly new lyrical type” that could transform “the mediocrity of daily life into a zone of illumination and poetic effusion” (Conversations, p. 67).

***

The question that inevitably arises here, I think, concerns whether or not the kind of image Reverdy and Breton advocated must necessarily be the product of unconscious, automatic processes in the mind. In the first Manifesto, as we have seen, Breton expressed doubt that Reverdy’s images could have been otherwise. Over time, though, he occasionally felt compelled to acknowledge that purely automatic writing was more of an ideal than a method that had reliably been put into practice. If, as Freud hypothesized, the unconscious can seep into and divert the workings of consciousness, then a seepage in the opposite direction is possible as well. If not probable.

But does the play of a conscious element in the construction of the catalytic image somehow attenuate its effect and disqualify it from providing the occasion for an existential-revelatory or poetic-imaginative insight? Would the intervention of premeditation prevent the image from creating the same “vital tension” ascribed to its purely automatic counterpart? Would that be enough to keep it from negating the real in favor of the imaginatively possible? I don’t think so. Regarding its capacity to reveal existential concerns, we must remember that conscious choices are themselves revelatory of being-in-the-world. And presumably, even actively created correspondences and juxtapositions of related phenomena ultimately are rooted in the semantic underworld, elements of which they bring up to the light of consciousness. Breton’s advocacy of unconscious processes—which in Surrealist practice was in any event frequently honored more in the breach than in the observance—represents one route a poetic methodology of the revelatory might take, but not the only one. Whether consciously crafted or unconsciously channeled, the kind of image Breton and before him Reverdy posited, when effective, takes us beyond the immediacy of the pleasure it provokes and points toward something that speaks deeply of the forces that produced it. And speaks as well to the corresponding forces within us as readers.

Daniel Barbiero writes about the art, music, and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century as well as on contemporary work; his essays and reviews have appeared in After the Art, Arteidolia, The Amsterdam Review, Heavy Feather Review, periodicities, Rain Taxi, Word for/Word, Otoliths, Offcourse, Utriculi, and elsewhere. He is the author of As Within, So Without, a collection of essays published by Arteidolia Press; his score Boundary Conditions III appears in A Year of Deep Listening (Terra Nova Press). His website is here.

References

André Breton, “Ascending Sign,” in Free Rein, tr. Michel Parmentier and Jacqueline D’Amboise (Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska Press, 1995). Internal cites to “Sign.”

André Breton, Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism, tr. Mark Polizzotti (New York: Paragon House, 199). Internal cites to Conversations.

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, tr. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan Press/Ann Arbor Paperbacks, 1972). Internal cites to Manifestoes.

Sigmund Freud, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, tr. and ed. James Strachey (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1989). Internal cites to Jokes.