George Salis: You were one of the founding members of the New York Group, a group of avant-garde Ukrainian diaspora writers. Can you reflect on your experiences with this group and what resulted from it? Can you tell us about some of the other writers who were involved in it?

Yuriy Tarnawsky: I arrived in this country in 1952, at the age of 18, and settled in Newark, NJ, across the river from Manhattan, which I started to visit on weekends practically from day one. There was a large Ukrainian community there (around 40,000 people), with a vibrant cultural life, centered around the Ukrainian Literary and Arts Club located at E. 9th St. and 2nd Ave., catty-corner from where the popular Ukrainian restaurant Veselka is now. There I became friends with a bunch of young Ukrainian artists and writers and participated in various events, which constituted sort of an informal artistic and literary movement. On Saturday, December 20, 1958, while having coffee at the Peacock Café on W. 4th St. near 6th Ave. (there is a Vietnamese noodle shop located there now), my writer friend Bohdan Boychuk, my wife Patricia (PN Warren), and I decided to start publishing a poetry journal Novi Poeziji (New Poetry) and to call ourselves the New York Group (NYG). Other young Ukrainian writers, from the U.S. as well as from other countries in the West, were invited to join in, and our membership, first being 6, over the years grew to 12. In addition to the three of us (PN Warren adopted the penname Patricia Kilina), in the original group there were E. Vasylkivska, B. Rubchak, and E. Andiyevska. W. Wowk, O. Kowerko, Yu. Kolomiyets, M. Tsarynnyk, M. Rewakowicz, and R. Babowal joined the group later over a stretch of a number of years. The goal of NYG was to modernize Ukrainian literature, especially its poetry, by forcing it to shed its traditional, neo-romantic poetics and replacing its socially-oriented, often patriotic themes with those dealing with the burning existential issues of the contemporary urban man. A yearly publication, New Poetry came out over fourteen years (1969-1972), publishing almost exclusively free-verse original works and translations of the works of the icons of Modernism. After Ukraine’s independence, 1990-1999, the group, in cooperation with the Writers’ Union of Ukraine, published in Ukraine a quarterly literary journal Svito-Vyd. Since then, it has ceased its activities, although some of the members continue being active as individuals. In all, over the years, the group and its members are responsible for over 200 publications. While teaching at Columbia, I was able to help found the archive of NYG at the University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, to which I contributed my papers. In 1996, we had a big inaugural opening of the archive with, as I recall, something like 4’x36’ exhibit space.

NYG is a unique phenomenon not only in Ukrainian literature but apparently also in that of the whole Slavic world in that its primary influence comes from Hispanic poetry. The works of many of its members show a strong affinity with Existentialism and often bear the features of Surrealism. I think it would also be proper to view it as a U.S. phenomenon akin to the Yiddish theater in the U.S. in the first half of the 20th century—a Ukrainian contribution to American culture.

GS: The following is from the jacket copy of your novel Three Blondes and Death: “Based on a complex mathematical scheme that the author, a computer scientist and linguist, developed as a substitute for the traditional architecture of a novel, and written in a deliberately sparse and structured syntax that ruthlessly compartmentalizes reality, Three Blondes and Death is an hermetic and hypnotic treatment of the classic themes of love and death.” Could you go into some depth about this complex mathematical scheme? Have you applied your computer scientist knowledge to other aspects of your work? Would you say that these techniques are an extension of the Oulipian tradition?

YT: The label “complex mathematical formula” is a bit misleading. It was the publisher’s idea, and for some reason I didn’t object to it. Let me explain what lies behind it. The rebellious spirit that I was at the time (1970), I wanted to write a novel which was not based on a plot, like virtually all novels that were written around me. But I had to have some other criterion on which to organize it. It was to be the story of a man and his love for three blondes and the simultaneous, unceasing drift toward death, so I decided to tell it in four separate parts. Hence 4 became a crucial factor in the book. With it in hand, I proceeded as follows. I wanted to break up the text into relatively short, autonomous sections. So, 40 appeared to be a reasonable choice. But having four parts with forty chapters each would have looked too uninteresting, too predictable. Besides, like the old weavers of Persian rugs who made deliberate errors in their masterpieces so as not to look too uppity in the eyes of Allah by aiming at being perfect, I decided to add 1 to the number of chapters in each part. I also didn’t want to anger him by pretending to be infallible. But having four 41s would likewise have looked too predictable and perhaps uppity, so I decided to add 1 to the first and the second digit, in other words, 11 to the number of chapters in part four, bringing the total number of chapters to 52. So, now 4 appears to have disappeared from the book. But 41+41+41+52=175, and 1+7+5=13, and 1+3=4, which, presto, is the magic number! Yet it’s hidden so far deep that maybe Allah, who is so busy with the daily affairs of the universe, will not notice it. I revert to using 4 also in other ways throughout the book, but it’d be too involved to discuss it here.

As I recall, I had read about Oulipo prior to writing Three Blondes and Death (TBD), but thought of it as a collaborative effort of a bunch of French writers, analogous to the collective French mathematical textbook authors known as Nicolas Bourbaki. Besides, they seemed to me to be engaged in writing something like sonnets, which was foreign to my intentions. It was only after TBD came out and I was talking about the book with Ron Sukenik at his place, with the book on the coffee table before us, that I learned from him more about them. As I recall, we talked then about the importance of form in a literary work, agreeing that form doesn’t contribute to the quality of a work, but that every good literary work needs a form. In other words, there are no good or bad forms, but whatever form is chosen, it must be strictly adhered to. Oddly enough, I still didn’t think at that time of TBD as being written in the restrictive mode, which it definitely is, not only because of relying on numerology, but especially because of the rigid grammar restrictions of the English in which it is composed. It was only after I met Jacques Roubaud and Marcel Benabou during their 2012 visit to the U.S. that I realized what I did was the same as what the Oulipians were doing. I gave them TBD as well as Meningitis, which is written in the same kind of restricted language, but they didn’t show any interest in them.

I appear to be somewhat strange in that I like both numbers and words, that is, mathematics and literature. In my writing, I devote as much effort to form as to language. Studying engineering was not a fluke, but a calculated choice I made, knowing where it would lead me. I feel I would not be the writer that I am had I chosen a different profession. But studying engineering didn’t plant these traits in me, it merely made them more proficient. I have composed a little half-page document I call “Self-definition,”* which I sometimes read in public, in which among other things I say, “Writing for me is akin to proving a theorem—the goal is to do it, and do it as elegantly as possible.” So, perhaps I should say that, as a writer, I was influenced by my technical background primarily by the methodology I learned there by applying it to my literary endeavors.

GS: You’ve worked as a computer scientist at IBM Corporation, specializing in natural language processing and artificial intelligence. How do you feel about computer-generated creative works, such as novels, poetry, and even digital paintings? In general, do you think we have to worry about an apocalyptic scenario involving artificial intelligence?

YT: I think it’s fine to use computers as tools for producing artistic works, be it literature, film, music, or the plastic arts, but I don’t think they will ever replace the human author. Computers can produce fine images and music, where patterns play an important role, but they cannot compete with people in arts that deal with emotions, such as literature. As long as there is no automaton that experiences the existential issues of a human being, no machine will be able to produce works that equal those written by a person. Such works can have great form, but will not project the emotional power associated with a well-written work.

There is a danger, though, that AI will have a destructive influence on literature, and that one day computers will churn out poems, short stories, novels, etc., on-demand, satisfying the needs of the market. I can’t help remembering the scary effectiveness of the early AI program ELIZA, which through simple parroting was able to fool people that they were talking to a human being. But, with the advances that have been made in the field, and even more so with those that are coming, the damage can be much greater. I’m saying “can,” but should say “will.” I don’t know how we should fight against this, but I know that we must.

GS: Your work at IBM involved a first-of-its-kind Russian-to-English automatic translation project. You’ve also translated works yourself. Are you of the mind that nothing is untranslatable?

YT: I think everything is translatable, but not always with the same success. In cases where form and content—phonetics and semantics, that is, words and meanings—are inextricably linked, such as in some instances of poetry, it may be virtually impossible to produce an adequate translation and instead something vaguely related may have to be created. Part of this problem may lie in the culture in which the source and the target language exist, making the problem even more difficult. But such cases are relatively rare. So, one can say that, practically speaking, everything is translatable, although some works more easily and more successfully than others.

GS: If you could have one of your works translated into every language, which would you choose and why?

YT: Hmmm…. That’s a difficult question. Can I say, all? I’m of a mind that all of my works are roughly of the same quality and I seem to like them all equally well (or badly), as I would with children if I had many. But I am probably wrong on this. Anyway, my answer—at one time I would have said, Three Blondes and Death, because of its size (some 250,000 words, and 450 pages) and the amount of time it took me to write it (more than twenty years), and also because of its radical nature, but now I will probably opt for The Placebo Effect Trilogy, partly also because of its size (some 150,000 words, and 700 pages), but also because of its nature. As you know, the trilogy consists of three books of five mininovels each, which are short works of fiction, whose effect is aimed to be that of a full-length novel. The genre is my own invention, and I think it is of some promise. Furthermore, with the trilogy, we are dealing with something close in aim if not in achievement to Balzac’s La Comédie humaine. There are something like one hundred characters in it. I should mention that by “placebo effect” I mean Man’s innate faith in his future, his will to live, which makes him fight on in the face of his always near, inevitable, and all-erasing end. In other words, it is a work dealing with the essential issues of Man’s existence.

GS: What is a novel you’ve read and think deserves more readers?

YT: I’ve been reading recently Roberto Bolaño’s huge posthumous opus 2666, and it would be nice if I would recommend it, but in all honesty, I can’t. It’s been praised to high heaven as being on the level with Márquez’ masterpieces, but, in my opinion, it is a work overpowering not in its mastery, but in its size. True, the amount of detail it carries is overwhelming, but the links connecting the various parts are tenuous and contrived, and, most crucially, its final, fifth part seems to me to be badly out of kilter, completely foreign to the preceding parts, as if written by a different, much less talented author. Bolaño was seriously ill when he was completing the book, which may be the cause of this, but you don’t get a pass on an exam because you’re sick.

I would recommend, however, the work of another Latin-American writer, one which Márquez considered his master, the novel Pedro Páramo by the Mexican writer Juan Rulfo. I read it in the original back in the 1960s, soon after it came out, and it left a profound effect on me. I reread it last year and found it to be as powerful as before. It is a masterpiece, not to be missed. I think it is barely known in the U.S.

GS: Your entire Placebo Trilogy is comprised of what you call “mininovels.” [About them Joseph McElroy said: “Tarnawsky’s are the second opinions we seek, almost recognize, then do, for they are made of the sounds, power sources, bizarre jobs, people coming our way, fitted together both by us and a culture by turns demanding and uncaring if we sleepwalkers notice or not: alarming, intelligent, caught again and again in the grasp of the author’s surprise and yearning.”] Have you thought of working on the opposite, gigantostories? Or is there a fractal effect involved with the Placebo Trilogy as a whole?

YT: Incidentally, at the IBM TJ Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, NY, my office was on the same aisle as that of Benoit Mandelbrot, who developed the concept of fractals. We said good morning to each other every day. I presume by “fractal effect” you mean repetition or replication of patterns. In that sense, no. I came up with the idea of the mininovel while working on the book of short stories Short Tails around 1997. I hadn’t written any fiction for a long time and was having a whale of a time trying out different forms. One of them was a series of short chapters with gaps in time between them when important things must have happened, but which are not described, thus forcing the reader to come up with his own explanation of what and how this took place. I call these gaps “negative text,” by analogy with “negative space” for “void” in cubist sculpture. Works like that, typically 15-30 pages long, when read, leave an aftereffect similar to that of having read a full-length novel. This happens because the reader has supplied his own information in order to properly perceive the work, becoming by this a co-author, together with the author of the mininovel. It’s a very rewarding genre, and I have written seventeen such pieces in total—fifteen in The Placebo Effect Trilogy, and two in the collection Crocodile Smiles.

But “gigantostories”—I think that’s what novels are, right? Especially the big ones, like Tolstoy’s War and Peace (I have heard it’s been renamed recently to Special Operation and Peace in Russian), Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, Bolaño’s 2666, etc.

GS: Your essay collection Claim to Oblivion deals with theoretical issues of literature, particularly language use. How would you summarize the overarching thesis of that collection? What about your creative writing manual, Literary Yoga?

YT: Claim to Oblivion is a collection of essays and interviews that were written over many years, in which I talk about literary issues of special interest to me, many connected with my own writing, so there isn’t in it one particular topic or viewpoint I focus on. But in general, in keeping with my nature, it is a series of arguments against the traditional view of writing.

In Literary Yoga I tried to sum up everything I have learned about writing over some sixty years and offer it for free (that is, for the piddling 16 dollars the publisher charges for the book) to anyone who wants to make use of it. I wouldn’t have given my arm and leg for it, but gladly would have signed over all of my royalties for the next ten years for a book like this when I was starting out to write. It would have saved me a lot of grief. It consists of a series of exercises the aim of which is to point out to the user the various choices at his disposal as he is composing and the effects these produce. The book is subtitled “Exercises for Those Who Can Write,” and may be used as a textbook or a self-study manual.

GS: This is a guest question from Max Nestelieiev: “Dear, Yuriy. What does it mean for you to write in different languages? Do you feel them differently? And what are the main advantages of the English language compared to Ukrainian?” I would also like to know how you would compare and contrast the English language with the Ukrainian language in general.

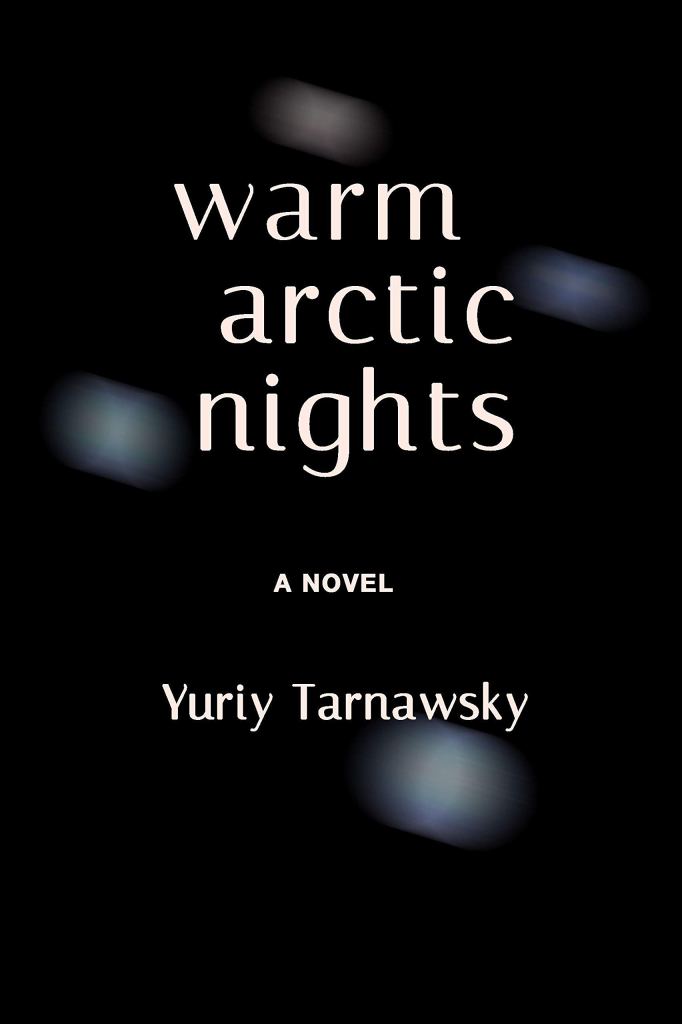

YT: Oh, it’s nice Maxym is with us. I enjoyed so much working with him on the translation of Warm Arctic Nights. He did a terrific job, and I am grateful for him having taken on that difficult job and having been so receptive to my suggestions, in particular, when I wanted to use more archaic language from Western Ukraine before the Russian occupation. I think we came up with a beautiful, organic amalgam of the past and the present.

As to the question—is it different for me to write in different languages? I have to reply in a strange way—yes and no. I think I’m equally proficient in both languages, and when I write, I seem not to feel any difference. But that must be only on the surface. I must associate different things with the word equivalents in the two languages, and as I write, I suspect, they pull me in different directions. These associations are partly what’s called in linguistics “semantic fields,” but also undoubtedly personal associations, conditioned by individual experience. So, when I choose to write in one language or the other, I must be deciding to write two different works—works similar on one level, but different on another. It’s a very thorny issue and is only partly explainable by the Saphir-Whorf Hypothesis, which maintains that speakers of different languages think differently because of the different languages they use.

There are advantages of writing in English because through it I have a vastly bigger audience. But also, I have drifted away from Ukrainian after having lived practically all my life in foreign-language environments, and am not as comfortable with the vocabulary, especially one dealing with everyday objects that have come into use within, say, the past fifty years.

I have completely different feelings about the two languages as I write in them—Ukrainian seems delicate and beautiful, like a fine China cup of translucent porcelain, and also, oddly enough, like a glass of crystal-clear water. English is chewy and pliable like a big wad of gum, or, better, of wood resin I am masticating as I build sentence after sentence, feeling its texture and savoring its redolent taste. I have noticed that sometimes I even move my jaws and tongue and swallow as I write, without being conscious of it, as if I was actually chewing on the words. English is God’s gift to humanity, and I am grateful to him for it.

GS: I’ve seen people posting photos of Ukrainian fiction that they’re now reading. I’ve also noticed some publishers offering deals on the Ukrainian fiction they’ve published. Do you think this is an example of “slacktivism” or is there something of depth there? What is the best way for people to help during the current war?

YT: I think it’s just people cashing in. They see the market potential and want to take advantage of it. But I hope the aftereffect will stay on.

GS: What do you say to people on the internet who claim you’ve “abandoned” your country or that you’re not Ukrainian because you’ve lived in the United States for so long?

YT: Is that what they are saying? I have published a couple dozen books in Ukrainian. Have they bought any? I have two volumes of collected poems in Ukrainian that are out of print and no one wants to republish them. I got an offer from a publisher—he’ll do it for $7,000 of my money, will keep 250 copies himself, and give me 250, to stick them up anything I want to. I can’t think for the moment of a hole big enough for them to fit in, so I’m making him wait.

I feel actually extremely comfortable writing in English while being ready to step into Ukrainian whenever needed.

GS: What are some of your fondest memories of Ukraine?

YT: Before the war. My father and mother young and healthy, I—a child, especially during summer vacations at my grandmother’s. Part one of Warm Arctic Nights.

GS: If you were in a room with Putin, what would you tell him?

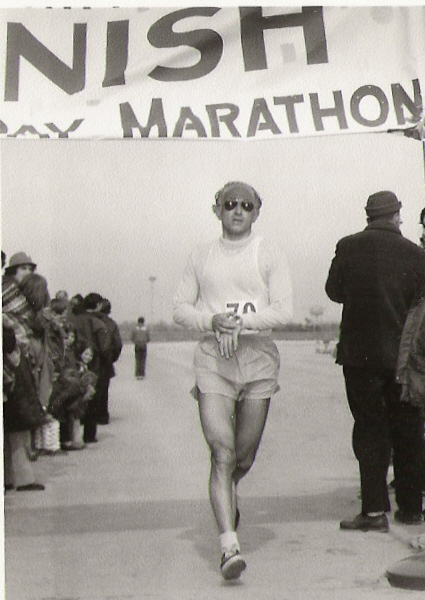

YT: Oh, I wouldn’t talk to him at all, but would tackle him instantly to bring him down. He’s a Judo expert and 18 years younger than me, but I was a marathon runner and used to be in great shape, and I’m sure I’d beat him as Ukraine is sure to beat Russia. Motivation, as everyone knows by now, means a lot–means at least three times as much as none.

I’d tie him down then and take him to Nuremberg, which is where the trials will once again be held and would attend his hanging, to which, I am sure, I would be invited.

But if I were to talk to him, I’d speak in profanities as you can speak only in Russian and as those twelve brave Ukrainian sailors on Snake Island spoke to the Russian flagship Moskva that soon thereafter was sunk by Ukrainian rockets, when they were ordered to surrender, saying, “Russkij korabl’, poshel nakhuj!” [Russian ship, go fuck yourself!] So, I’d say, “Russkij pizdjent, poshel nakhuj.” [Russian pussydent [actually much worse than that], go fuck yourself!”] I certainly wouldn’t try to reason with him. He doesn’t have a mind, just the reptilian brain.

GS: You’re working on a novel titled Sebastian in a Dream, which you’ve said is “inspired by Georg Trakl’s poem ‘Sebastian im Traum’ and patterned on J. S. Bach’s ‘Goldberg Variations.’” Can you reflect on this poetic impetus and tell us how the writing process has been unfolding, particularly in relation to the musical structure? When can we expect to see it published?

YT: Bach is the pinnacle of mastery for me and the Variations one of the finest instances of it, and Trakl is one of my two favorite poets, the second one being Rimbaud, and “Sebastian im Traum” is my favorite poem of his. I followed the aria-thirty variations-aria pattern of the Variations in the novel, and used the beginning of the poem “Mutter trug das Kindlein im weißen Mond” [Mother carried the little child in a white moon] as the phrase for the aria, and then bounced off it thirty times. It’d be too involved to say more about it. It was the most difficult book I did since TBD. It’s finished, and I have a publisher or two looking at it, but haven’t really started looking for one seriously. I have in the meantime started to work on another novel, a potential companion to Sebastian in a Dream, based on one of El Greco’s paintings. I don’t know if it’s going to pan out so I’d rather not say anything more about it.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting TheCollidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

*self-definition:

For me writing is a highly personal endeavor, an existential act, through which I am able to be myself—I write, therefore I am.

Although there is virtually no raw autobiographical data in my writing, all of it deals with subjects and themes that occupy me and which have been stirred up by the events in my life. I am a very private person and feel uncomfortable disclosing to others the details of my biography. Besides, imagination is so much more powerful than everyday life; compare the incredible—scary or exhilarating— experiences we live through in our dreams at night, to the drab events we trudge through in the daytime. It is for this reason I frequently turn to dreams in my writing. They enable me to create more effective works, with greater impact on the reader.

My technical background has had a profound impact on my writing, causing me to devote much attention to language and form. I am not concerned with how readers will react to my work. Writing for me is akin to proving a theorem—the goal is to do it, and do it as elegantly as possible.

Yuriy Tarnawsky – February 17, 2015

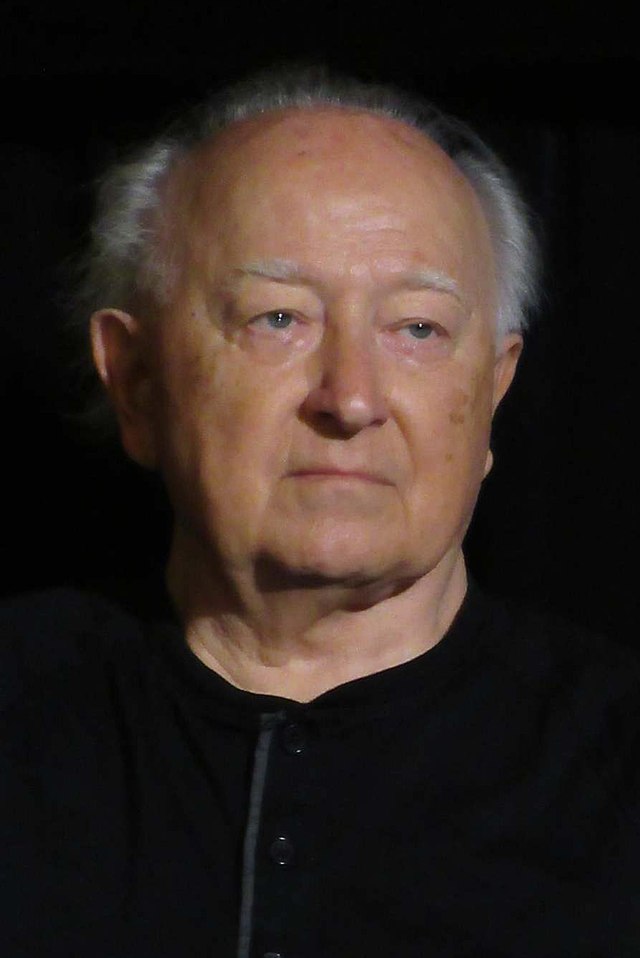

Yuriy Tarnawsky (born February 3, 1934) is a Ukrainian-American writer and linguist, one of the founding members of the New York Group, a group of avant-garde Ukrainian diaspora writers, and co-founder and co-editor of the journal New Poetry, as well as a member of the US innovative writers’ collaborative Fiction Collective. An engineer and linguist by training—he holds a Ph.D. in linguistics from New York University—he worked as a computer scientist at IBM Corporation, specializing in natural language processing and artificial intelligence, and as a professor of Ukrainian literature and culture at Columbia University. He has authored more than three dozen books of fiction, poetry, drama, and translations, working in both English and Ukrainian. Some of his books include The Placebo Effect Trilogy, Three Blondes and Death, The Iguanas of Heat, Crocodile Smiles, and Modus Tollens: Improvised Poetic Devices.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.