About G. F. Gravenson: “He has spent many years in publishing and journalism. He brings to this book a careful and thorough professional objectivity for his subject matter as he attempts to separate fact from fiction in the events that surround the disappearance—now explained—of the deeply missed Sweetmeat twins, Paul and Pookie.” – From the dust jacket of the original edition.

I interviewed the author here.

“and all the worlds were worlds apart/ with a hundred tongues and a thousand meanings/ the tower of babel/ babbling away on molecules of misconnections”

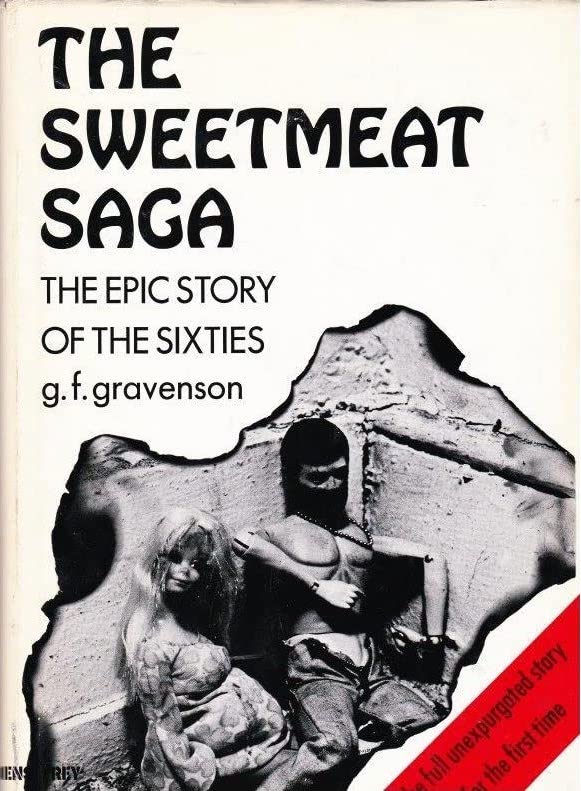

G. F. Gravenson’s The Sweetmeat Saga: The Epic Story of the Sixties is not a saga nor an epic as such, but it’s literally and metaphorically writ large, featuring a seismic event concerning “mr. and myth america.” That is, the prodigy rockstar duo known as Pookie and Paul Sweetmeat. Forget the assassination of JFK or MLKJ, forget the ongoing Vietnam War, or better yet, internalize that tragic panic, for the Sweetmeats have gone missing!

It should be noted that this novel belongs to the long tradition of literary hoaxes, beginning with what many refer to as the first “modern” novel ever written, Don Quixote. Aside from The Sweetmeat Saga’s cover sensationally announcing “the fully unexpurgated story for the first time,” the jacket flap copy claims that Gravenson “spent nearly two years researching newspaper and magazine clippings, film clips, TV kinescopes and videotapes of the Sweetmeat twins,” and even eyewitness accounts. Although it’s uncertain how many people bought into the hoax (the Times reviewer didn’t), between the War of the Worlds radio scare of the late 30s and the sex-trafficking Pizzagate of the late 2010s, people have proven themselves to be highly gullible, dangerously so.

This “true” story involves a copious cast of kooks, crooks, Cronkite types, and more, and plenty of Pynchonian names to complement these personalities, including Sonny Swingle, Manny Makemore, Marvin Tempest, Forest Jagoff, and Reverend Cecil Buttermilk. Delightful but not too surprising considering that this book was published almost a decade after Thomas Pynchon’s V. and five years after The Crying of Lot 49, although it does predate Gravity’s Rainbow by a couple of years, and the same Time magazine reviewer of that 20th-century monolith also reviewed, semi-favorably, Gravenson’s first and last effort when it appeared in 1971, calling it an “entertaining and satirical look” at the infosphere’s “encircling layer of electronic and typographical smog….” Continuing with the eccentric names, the reviewer in question is R.Z. Sheppard and he refers to Pynchon’s masterpiece as a “sustained bombardment by a remarkable mind and talent,” saying that the novel is “about man the symbol-making animal desperately trying to build a protective system of meaning over his head while at the same time blind technology increases the odds that something will bash his head in” (I can’t resist mentioning that he even reviewed DFW’s Infinite Jest in 1996, dubbing it a “marathon send-up of humanism at the end of its tether” and full of “generous intelligence and authentic passion…”). Although Pynchon’s and Gravenson’s novels are vastly different, they do share temperaments and themes when explicated this way, for The Sweetmeat Saga is also a sustained bombardment that never lets up even if the text is more spread out, like a swarm of lexical insects stuck on oversize flypaper (more precisely, A24 typewriter paper that had to be photocopied to stay true to the text placement, as with the work of Arno Schmidt), and the length is much shorter at 241 pages in the first edition brought out by Outerbridge & Dienstfrey.

Back to the characters, Max Vogel is both the Sweetmeat’s agent and their legal guardian ever since their parents died in a car accident. They haven’t even reached the age of 21 yet they’ve mastered almost every instrument, including “guitars banjos pianos flutes violins washtubs french horns jew harps you name it.” Millionaires before they were ten, they had drawn “bigger crowds than kennedy or nixon,” suffusing the culture more than those noxiously omnipresent Marvel IPs, and with an equal amount of branding:

pookie and paul teapot spout cleaner

pookie and paul pail and mop handle

pookie and paul blower and barbeque (portable)

pookie and paul golf cart umbrella attachment

pookie and paul furniture wax rags

pookie and paul shaft safety lock

pookie and paul trailer dolly

pookie and paul dental floss applicator

pookie and paul recording pill dispenser

pookie and paul self service table

pookie and paul hip thigh crutch

pookie and paul anti-backlash fishing reel

pookie and paul drain guard

pookie and paul electric door jamb/ but that was only a beginning

Yet at the time of their disappearance, their fame had been experiencing a downswing (“i stopped collecting their records,” chimes in one anonymous voice), suggesting that the whole thing might be a publicity stunt. Although almost everyone loves these tuneful twins, or the memory of loving them, some people are certainly indifferent while others call their output “commie gook music,” and then there’s Stuart the psychotic would-be killer and his therapist who has the oedipal appellation Doctor Mountmother. Unsure of who or what to target, Stuart wants to kill himself or his doctor, no…the Sweetmeats for being the paragon pair with which his mother had constantly compared her subpar son, a Mark David Chapman in the making, but he’s far from a genuine antagonist in this story, merely a furious face in the crowd. A larger threat is the rumor-turned-conspiracy regarding the Russians, in which the Sweetmeats are “unwilling tools of those monsters/ possibly through hypnosis” and eventually leads to the military being dispatched.

The fissured prose is rife with many amusing turns of phrase, sometimes literally, such as “no tern was left unstoned” and “due to circumcisions beyond our control,” but that’s far from it. Other than slang spelling (“mustuf,” “whasmadder, “whacha”), we get sermons, Vietnam news reports, eavesdropped conversations, technical jargon, pastoral prose, an excerpt from Dr. Mountmother’s “Manifestations of Adolescent Fantasy,” racism, homophobia, paranoia, song lyrics and jingles, groovy radio announcers, a Cuban’s broken English, the sufferin’ succotash speech of a grandpop with denture trouble, scenes from a terrible porn script titled Lust Weekend, a procedure evaluation questionnaire, and even a dose of Morse code, not to mention some questionable commercials that were probably informed by Gravenson’s own stint in that industry (“YES FRIEND,/ CRASS IN A GLASS HAS CLASS –/ CRASS BEER THE ONE BEER YOU HAVE/ WHEN YOU FEEL LIKE IT”). All this in the boiling pot and Gilbert Sorrentino’s Mulligan Stew was still about a decade out and William Gaddis’ J R closer to half a decade from appearing on the scene. While the book is without a doubt alive with voices, it’s too bad the mythic musicians’ ditties didn’t jump out of the book as it did with Salman Rushdie’s literary rockstars in his turn-of-the-millennium novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet—the title track, as it were, becoming an ethereal song by U2. This despite Gravenson having written a handful of the songs, yet such an occurrence was recently close, and could still be one day, because the 50th-anniversary Tough Poets Press edition of The Sweetmeat Saga includes the lyrics sheet for one of the songs, titled “Take Back America.”

(That the book is an archeologically-preserved product of its troubled time is highlighted by my own first edition copy, which is inscribed by Gravenson and dated 2/23/73: “To Marty — Sorry about not being a fag. The best, Guy,” and came with a large photograph of a dapper-suited man sitting on a leather couch, complete with cigarette and wedding ring, smile-sneering at someone or something leftward. When I emailed Guy about it, who has been living in Bucerías, Mexico for much of the proceeding half a century, he couldn’t remember the occasion and said the photo isn’t of him, suggesting it could have been what’s now referred to as a “thirst trap.” If Guy had had an illustrious career marked by regular bestsellers, maybe he would have eventually become a victim of the modern and extra-tainted infotainment that now bombards us, canceled and ridiculed if not threatened for a mere inscription he wrote many decades ago, likely as a jest of bad taste rather than some book-signing hate crime. Fodder for those itching for something to get worked up about now that Pookie and Paul will never manifest again, the urgency of their memory a memory of a memory if nothing more.)

Where is this telegrammatic and telepathic torrent heading? Sometime after their disappearance, they’re reportedly sighted, and thus Big Sur morphs into a kind of Mount Sinai, fans mixed with military mixed with others caught within the uphill human flood, yet instead of the climax one might quixotically hope for in such a situation, the final scene intentionally swings from musical holiness to ubiquitous bathos. In some ways, this is an extremely oblique coming-of-age story, especially in the context of adolescent fame, because the disappearance is timed for their 21st birthdays. Double debutantes who taunt but don’t debut. More than that, Gravenson’s debut novel is a plunge into the fervency of faith, the kind of mass delusion that Leon Festinger so fascinatingly and hauntingly documented in his landmark study from the 50s, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World. And when it fails, the faithful believe with even more depth, shallow though their epistemology is, if the word’s even applicable. Yet in the book’s story and also the story of the book, the opposite happened: people forgot, a case of mass amnesia almost, except for the remaining faithful few. Thanks to the efforts of Tough Poets Press, readers can begin to remember, even if they have no memory of it, because the pseudo-history wrought by Gravenson is as permanent and textured as tablets, a far cry from the ephemeral nature of a social media feed even if there is a time-jumping overlap in each experience, so, “mah fellah amuricuns,” stop scrolling and turn the plus-size pages of an experimental classic instead, ignoring the character Hy who claims at the end, as though rebelling against his creator à la Sorrentino, “The Sweetmeat thing is a dead issue. It was the biggest bummer, the biggest nothing of the Sixties. A hoax.”

Editor’s note: The aim of Invisible Books is to shine a light on wrongly neglected and forgotten books and their authors. To help bring more attention to these works of art, please share this article on social media. For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.