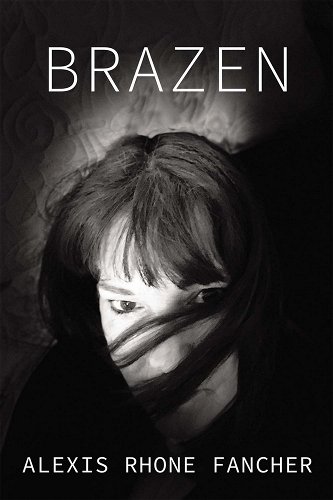

L.A.-based, internationally-renowned poet and photographer Alexis Rhone Fancher doesn’t need introductions. Brazen—her ninth poetry collection, just released from NYQ Books—probably doesn’t either, as it speaks loud and clear from page one. The approach, as Fancher’s readers know well, couldn’t be more direct. You are in before you know it.

I have heard many of the poems collected in Brazen viva voce, on Zoom or—luckily—in person. They all left a trace—a distinct, separate imprint, thanks to their size (they seldom exceed one page), their shape (they are tridimensional, sculptural), their incisive, frequently indelible endings. Reading the book is different, as pages interweave and accrete into a consistent fabric that spreads even “in absence,” permeating our mood, day, surroundings, as it happens when we are sucked into an unforgettable novel. Such effect is due to the exceptional coherence of the poetic I. It’s the kind of I that (paraphrasing Salinger) you’d wish was a dear friend of yours, so you could call her any time.

“Noir” is one of the adjectives most used to define Fancher’s work. Brazen doesn’t deal with crime (knives and bullets make sparse if striking appearances, but in the symbolic domain). It is true, though, that we fall for the poetic voice as we do for some fictional detectives whose success in solving the case is sheerly collateral, as is the case itself. The only thing that counts is how they think, or else muddle through—their inner monologue. What counts is their gaze, the unique way they have of looking at things—how bad the world looks to their bullshit-proof eye, and yet not un-beautiful. How overwhelmed they often are, yet not entirely hopeless. And we feel that if they could also glance at our life—the trivia, the broken faucet, the unpaid bills and such, the doubts and dilemmas—they would figure it out, and all would make sense.

Brazen is about gaze and clear-eyedness. About seeing reality as it is, then deciding to apply a filter or two for illusion’s sake. Seeing it still—beyond illusions, delusions, lure, and mirages. Name it. Love it anyway.

What here falls under scrutiny is desire in its multifold components, variations, mutations. Desire, aka the stuff that makes us move, get out, seek, go get what is missing. Mainly, in an urban setting—and the landscape is accordingly toned. It is made of bars, motels, cars, parking lots, and cell phones—transit sites where solitudes intersect. Sites of “crossing”—sex (consumed or attempted, failed, stolen, dreamed off, bragged about, longed for, recalled, fantasized) being the most literal embodiment, the aptest incarnation of such human need. It is made (the landscape) of people themselves.

Fancher’s black and white photography punctuates the poems—a discreet yet studied descant, never obvious. The juxtaposition of images and text provides keys of interpretation to the book as a whole.

Many iconic poems, for instance, haunting, lapidary, high-density, are the equivalent of those shots where the gray scale is gone. Details are erased. Extreme light and dark create a pattern that strikes us “at first sight,” etching itself like a cipher, a symbol. See the cleavage on page 52, the sun-glassed look on 85.

The iconic poems, yes—which gather in a fistful, which distill into liquor the main themes of the book—are many. One of them, “Thirst,” beautifully expresses the motif of water-draught-drink-dryness that runs through the collection, sealing the equation between place—here, this town— and the bodies echoing its fight for survival. “Like my love life, L.A. is in a perpetual state of drought.”

From “Clueless”:

… a toxic longing so deep you can draw water. He’ll drink it up, suck you Sahara.

From “Thin-Skinned”:

That winter you squeezed the juice into goblets, overflowing. You poured your love into me. But Spring came. The knife bled. Something stupid I said. You, and the oranges, turned bitter overnight.

Thirst for emotional nurturing, for love that, like water in a desert, is a scarce resource in very high demand. Precious and elusive. Never to be wasted. Quickly evaporated. Always spilled.

Desire spilled, therefore un-satiated, therefore insatiable. “Why We Didn’t,” the first poem of the book (also iconic), sets the tone. What here doesn’t occur is intercourse, when ripe adolescence makes it the only way to salvation, the universal placebo, the passport to the future, the proof of one’s right to live—when the body and soul agonize for it. Intercourse also doesn’t happen in “Once, at fifteen, in a field in Camarillo, I picked raspberries,” a brief poem that is both ethereal and scorching:

“But I was a dandelion;

he blew me off,

his rebuff a field of bitter fruit

that left me stunned for years.

Even now, at a party, when

someone asks what field I’m in?

I am always in that field,

ripe, stained,

waiting.”

Then, obviously, sex happens and the initial lapse is atoned (is it?), but the spill of desire remains, taking many forms of rejection, abandonment, and abuse.

Not all aspects of this waste are painful. Or they are, but often the poet’s gaze zooms out, takes in the wide picture, minimizes the drama and injects humor by the gallon. No doubt, it’s a female gaze, subverting the usual perspective—scanning everyone, everywhere, but men in particular, seeing some of the gender’s stereotypes, alas, in their risible vanity. Here are the narcissists, the predators, the manipulators, the violent, the oblivious, the hypocrites. They all could be recapped by the “Famous Poet,” to whom Fancher devotes eight poems and a stanza, spread throughout the collection.

Meta-literarily speaking, those cameos (randomly sparse) perfectly represent the “Famous’” nature and plight—how he’s utterly lost and simultaneously stuck, his memory a mush, oblivious of his interlocutors’ identities (and of his own, indeed), only moved by the immediacy of a primal need from which he never weaned. We could think that he is the farcical element classically interposed between the acts of a tragedy, and we do, until poem number eight—“The famous poet is silent for six months”—opens our eyes. Yes, she sees him for good, pathetic and all. She loves him anyway.

Desire wasted, love un-found—we said—has many garbs. Diverse apparels, as we learn in “Dress Rehearsal,” which equates sexy clothes with different forms of death. The idea is further excavated, eerily amplified in “Regret Is a Dress to Be Buried In.” Here, Fancher weaves the ball gown (an heirloom, and exquisitely wrought) donned by her mom on her 20th anniversary with the cancer knitting itself to her organs from the inside. Frida Khalo’s art comes to mind, evoked by Fancher’s verse.

Frida, and the accident. “My Body Is a Map of Scars” summarizes the hyper-vulnerability suffered by those who have been previously hurt. Wild animals (even domestic ones) never show pain. They hide their wounds, knowing that nothing excites predators like the sight and smell of blood. Hurt preys are easy preys. Damage causes more damage. The offended body seemingly calls for further offense. Though, the same poem underlines, en passant, the survivor’s exceptional resilience. Beware. “Look at my palm: see how the lifeline ends and then restarts?”

Brazen is a book of “parts” aching to be seen as a whole, and of “wholes” relentlessly dissected, reduced into parts (a concept, by the way, which ironically resonates with the origin of the word “sex,” which means sectus, divided). Hear “Lola, the Human Vagina…” :

“I make sure they see me

as a whole person, she said.

(…)

I try not to laugh.

I too tell myself lies.”

From “Tonight at last call, J. calls me his Brown Liquor Girl again,” :

“When I ask him which part of me he loves best,

J. answers: What’s missing,

tonguing the place where my nipple had been.”

From “Pas de Deux” :

“When I found the photos with my eyes x’ed out,

I knew I would leave her.

My eyes—my one good feature.”

A “part” that keeps wandering off, and I find particularly compelling, is hair—single one, found in a dish, belonging to the poet herself—“a strand of myself in every serving”—or to some of the waitresses parsed throughout the collection in guise of alter egos. The hair will return, en masse, towards the end of the book. In a stunning prose poem (“In the Drink”), flanked by an equally striking photograph, it’s a “tangle in the wind” while the broken-hearted speaker self-guillotines, sticking her head between the posts of a pier. Meanwhile, the waves slap—“a lull so docile you’d never imagine their rage.”

Only in the six poems that are namely, officially piecemeal (odes to the poet’s husband body parts), do the segments compose an unmistakable, irreplaceable unity. Only those parts, contrary to what happens in all the other instances, all the other crossings, cannot be replaced.

While the entire book is built as a savvy embroidery with threads hidden, emerging now and then to form an intricate yet balanced design—themes and characters intermittently surfacing, drawing loops and figure eights—the “husband’s body parts” poems are joined, compounded. They create an oasis amidst desert land, a cool place with its distinct weather. If the book traces a cartography of desire, the sextet is a miniature map of pleasure, hence providing a radical change.

I had the luck of reading those poems when first published in Rat’s Ass, where nine of them appeared. Happily surprised to find them again in Brazen, I was slightly dismayed on seeing that not all were there. Later, I appreciated the choice of culminating and closing on poem six, the one dedicated to the heart. In particular, on its last stanza:

I hold my breath — will time to stop

in this heady space. Let us linger in his tenderness.

I love how the verse captures and holds the main difference between desire and pleasure—the first being, as we know, what sets us in action. The second, what makes us want to stay.

The “husband poems” are a country of their own, also due to a shift of lens—so to speak—in the poetic camera. The landscape is no more what we have witnessed so far (people wandering through bars, phones, cars, diners, streets, apartments from which they briskly enter or exit, beds or couches always visited in some haste, redolent of both insomnia and nightmares. Beds or couches resembling, as well, a sort of transportation).

Switch of lens, and the body becomes the landscape—somehow wider, more pleasant, way more inhabitable.

Toti O’Brien is the Italian Accordionist with the Irish Last Name. Born in Rome, living in Los Angeles, she is an artist, musician, and dancer. She is the author of Other Maidens (BlazeVOX, 2020), An Alphabet of Birds (Moonrise, 2020), In Her Terms (Cholla Needles, 2021), Pages of a Broken Diary (Pski’s Porch, 2022), The Past, Ineffable (Cholla Needles, 2023), Odd Arcana (Cholla Needles, 2023) and Alter Alter (Elyssar, 2023).