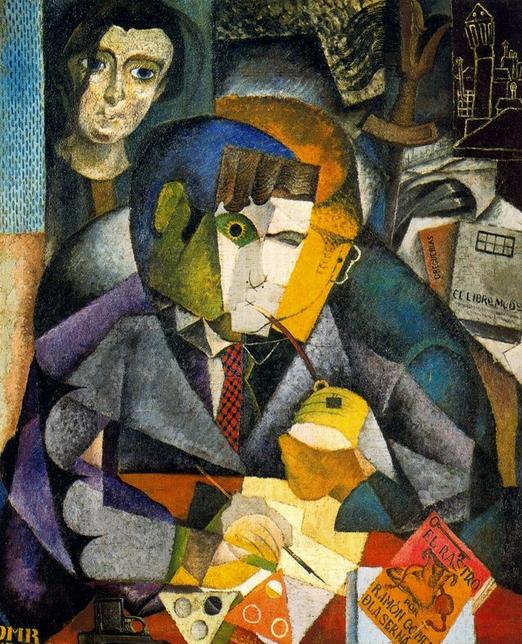

About Ramón Gómez de la Serna: One of the most original and prolific modern Spanish writers, de la Serna (1888 –1963), who liked to be referred to as simply Ramón, was an early exponent of avant-garde and surreal writing. During his lifetime, he published more than 90 works in a variety of literary genres, only a handful of which have been translated into English. He is considered the father of the greguería, a Spanish and Latin American literary genre consisting of short prose poems that roughly correspond to comedy one-liners. Surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel credited Ramón as being one of his strongest artistic influences. The two collaborated on the script of what would have been Buñuel’s first film, Los caprichos, but it was never produced. Octavio Paz, recipient of the 1990 Nobel Prize for Literature, wrote of Ramón, “For me he is the great Spanish writer.” And Pablo Neruda, also a Nobel laureate (1971), claimed that “the major figure of surrealism, in any country, has been Ramón.”

There is something in the landscape that keeps them quiet: it is a house which bricklayers and painters are finishing up—the city that will burn tomorrow in the film The Big Fire.

“It’s too bad that a city so carefully built is going to be destroyed,” remarked Jacques.

“But we’ll make a film…. This city will live longer than those other cities now standing up that will never be filmed!”

Hollywood, already long notorious for its unreality, becomes a fantasia of a fantasia in Ramón Gómez de la Serna’s Movieland, first published in 1930. The author holds a funhouse mirror up to a funhouse mirror and describes the fractal film freaks, the panoramic prima donnas, the smizing villains, and plenty of others in this menagerie. In fact, the novel partly reads like a cine-bestiary this side of Borges’ The Book of Imaginary Beings, giving us fake bullfighters, Elsa the Movieland Queen, a woman’s stolen beauty spot, a spoiled child actor, absurd cocktails, a chameleon thespian whose “whole psychology changed with every rôle,” Emerson the Movie Emperor, and then there’s quite literally a beast: “Movieland’s most fantastic animal, one who differs from all imaginable animals, is a crocodile that once upon a time had to be a dinosaur; that is to say, during the making of Movieland’s most impressive prehistoric film he had to wear a bony crest and imitate a dinosaur by walking majestically and adapting his gestures to the orders of the stage director.”

The research-consumed William T. Vollmann would likely balk at the following postscript in translator Angel Flores’ insightful introduction: “Ramón has never been in Hollywood. Not even the U.S.A.” I’d claim that this lack of firsthand experience breeds a more imaginatively fertile surrealscape. Of course, it’d be going too far to say the author has no notion of Hollywood whatsoever. Despite having written this novel in his homeland of Spain, he doubtlessly experienced that type of American propaganda we almost all succumb to, that of watching the Hollywood films themselves in all their silver screen glory, their lullabies of tempting lies, their melodies of melodrama.

Rather than a traditional plot, the book is comprised of vignettes describing aspects of Movieland, with some characters crossing over and developing their relationships and ambitions but coming and going with shooting-star speed. Thus, the eponymous Movieland itself becomes a kind of omnipresent character. Think Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities for a sense of the structure and the mostly bird’s-eye narration, not to mention the generous dose of magical realism, a wholly appropriate sensibility for the subject at hand. It wouldn’t be too hard to imagine Movieland as an entry in Calvino’s catalog, except this is a city that’s all too visible. The translated prose is often as rich as Calvino’s, and rife with cinematic analogies, the lens seen through a lens, so to speak. Here are two early examples of the latter: “The tourists moved jerkily, like flickering films” and “The guide, like the subtitles in a film, passed on quickly through the streets….”

Some chapters contain several vignettes in one. As a result, more than a handful feel underdeveloped, lacking yet deserving the same attention as the single-vignette sections. In that sense, they’re like actors vying for the starring role, but I doubt that was de la Serna’s intention. The last quarter or so of the novel loses some of its original power, but it also picks up a more stable narrative thread in Carlotta, a Lolita-like star who comes out of nowhere and dethrones Elsa the Movieland Queen, who is later reduced to opening a Kissing Academy in which she coaches aspiring actresses in the art of the silver-screen smooch (the Kissing Academy is one of several delightfully inspired institutions, the bleaker ones being the thespian nut house known as the Museum of Expressions and the Asylum for the Blind, for those who have slowly lost their sight from the powerful lights of Movieland). In addition to Nabokov’s nymphet, Carlotta is also like Márquez’s Remedios the Beauty in 100 Years of Solitude: “No one knew how it was accomplished, but the whole universe became new and exciting at the girl’s least gesture. All men who saw her resented or forgot the women they had known before. […] She was like silken paper spread to hide all the defects and the failures of the world.” Of course, she is soon doomed to the darkness of Movieland, a place that does everything to conceal real-life tragedy lest it stain the perfect promises sold by celluloid.

(Beware: there are sections on “The Japanese,” “The Negroes,” and “The Jewish Quarter,” which turn racist stereotypes into outright hyperboles. Modern readers could easily find these sections offensive, but whether or not de la Serna believed in these stereotypes is anachronistically irrelevant. The sections show how these minorities were viewed and treated back then (and to this day) while also fitting the novel’s general cartoonish tone. No one comes out of these stories looking like a paragon.)

Despite the blistering critique (“‘The soul is cremated while the film is being shot…’”), there’s an undeniable degree of marvelous awe, even at the outset: “Movieland looks like a Constantinople combined with a little Tokyo, a touch of Florence and a hint of New York. […] It is like a Noah’s ark of architectures. A Florentine palace, seized with that salaciousness which exotic buildings produce, looks longingly at a Grand Pagoda,” but then a more critical comparison at the page’s bottom: “To stroll through the streets of the city is like a nightmare, and the stroller becomes a circumnavigator who tours the world in an hour.” And it only gets more excoriating from there.

Hollywood has been a freakshow of out-of-touch caricatures for longer than one might realize. Despite being written less than two decades after the birth of Hollywood, the sweeping satire remains relevant almost a century later. Regardless of talent, Jared Leto and his Echelon cult would fit right in with the rest of the circus, likewise the Scientologist stunt devil Tom Cruise, the coffee-douching Gwyneth Paltrow, the exiled rapist Roman Polanski, the pillow-shitter Amber Heard, the post-car crash computer-generated Paul Walker, and the list goes on like a never-ending credit sequence.

In a kind of onanistic act, Hollywood has produced plenty of films about itself, not all of them as self-serving as one may suspect. A Star Is Born (1954), for instance, more than hints at a deep darkness in those who yearn for a persistent spotlight, and the same is true of The Artist (2011), even if it ends on a much happier note. And then you have a different beast altogether in Damien Chazelle’s epic masterpiece Babylon (2022). Like Movieland, Babylon disregards historical facts to present (mostly ungrateful) viewers with a maximalist film that blends genres and styles in a sensorial bacchanalia, culminating in the Big Bang that gave birth to cinema until the colors that make up the stuff of film finally bleed into each other and all that’s left is an abstract concoction of feelings. And like Movieland again, there’s a mixture of critique and awe in the motion picture, going further into the realm of outright nostalgia (a commodity of Hollywood more in demand than ever, it seems).

Damien Chazelle is a known jazz fanatic, and Babylon isn’t his only film to feature a jazzy score. If he were to read Movieland, I’m sure he’d appreciate the several mentions of his favorite genre, including, right off the bat, “the noise of jazzbands, the lunacies of xylophones,” which often provided silent films with their soundtracks. As it happens, a phenomenally visceral scene in Babylon highlights the difficult transition to talkies. Curiously, de la Serna doesn’t highlight this momentous transition. Still, true to his fantastic imagination, he describes a futuristic “seeing sleep” method of experiencing films that will only come out once the cinematic powers that be sense the imminent downfall of Hollywood, a top-secret backup plan prescient in its similarity to virtual reality, that digital opium den. Later in the novel, this from someone who may not even be aware of the “seeing sleep” invention, but simply cinema proper: “‘The thing we are loosing on the world,” said the most disillusioned of the group, ‘is a gigantic tapeworm.’”

Admirably enough, Spielberg’s autobiographical Hollywood bildungsroman The Fabelmans (2022) takes a sober look at his urge to make films beyond the need to control the uncontrollable, embodied in a scene where young Spielberg observes his clashing parents with an almost clinical desire to frame them, not fiddling while Rome burns but filming, fetishistically so. The tapeworm, or more accurately, the filmworm, runs deep, yet it can breed such amazing art, within Hollywood and without, from Georges Méliès’ Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902) to Ari Aster’s Beau Is Afraid (2023).

Flores mentions in his introduction “at least half a dozen significant novels” by de la Serna, including Black and White Widow, “considered by the Paris-Journal—hurrah!—among the five greatest works of fiction of our generation….” It’s truly a literary crime that only a handful of de la Serna’s works have been translated into English, most of them mere hors d’oeuvres, and Movieland, the most substantial example of his translated oeuvre, was out of print for decades and decades until Tough Poets Press came to the rescue with a new edition (alas, the translator isn’t listed on the cover, an unfortunate oversight). Simply put, Ramón Gómez de la Serna deserves more attention from the English-speaking world.

Editor’s note: The aim of Invisible Books is to shine a light on wrongly neglected and forgotten books and their authors. To help bring more attention to these works of art, please share this article on social media. For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Listen to a discussion of this book between George Salis and Matthew Taylor Blais on The Collidescope Podcast:

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.