George Salis: Your first novel features characters who lament the “state of the Jews.” How would you say this state has changed in Boston and in general?

Mark Jay Mirsky: The first novel, Thou Worm Jacob, was begun while I was a senior at Harvard in Albert J. Guerard’s fiction seminar. Guerard, a brilliant critic who also wrote novels and short stories, was someone committed to the experiment in fiction—which he called “anti-realism.” The novelist John Hawkes was his student and disciple, and Hawkes was taken aback when Albert, who had adopted me when I entered his fiction seminar in the fall semester of my senior year, teased him, introducing me to Hawkes at a Harvard Advocate party. (The official literary magazine at the college. They never accepted any of my fiction, but I attended as a guest of Albert.) Albert boasted that I was “the only other anti-realist” in Cambridge. (Though Hawkes was already teaching at Brown in Providence, Rhode Island—he came to lecture in Albert’s class on 20th-century fiction. I remember a spectacular performance by him linking Shakespeare’s Hamlet to the work of Norman Mailer—lines of which still echo in my head: “Norman Mailer is a baseball player up at the bat. The bases are loaded. With every swing, he swings for a grand slam homer. Only he doesn’t know. The grandstands, the stadium, is empty!” The rest of the lecture, or what I could recall of it—he had a wild oratorical style, but with a screeching voice that somehow suited his wild metaphors—was that the play Hamlet was all about the “ear.” That remark has made more and more sense as I grow older. I could talk for quite a while about Hawkes, Guerard, and me (if you so desired).

I took Albert’s classes both in the fall of 1960 and the spring semester of 1961. I wrote my second decent story in his class (today it would be called a “workshop”), but I submitted one I had written the year before when I applied for the seminar, called Shkootz (it was published in an independent journal in Cambridge, Identity, edited by James Manchester Robinson). The story’s irony had fallen on deaf ears in my previous creative writing class, probably because the bitter Jewish self-mockery escaped the professor, a dyed-in-the-wool Yankee. There were two important fiction workshops in the fall semester of my senior year, Archibald MacLeish’s and Guerard’s. MacLeish was not impressed by the story either. It began with, “So it was Epstein, the butcher’s boy, who had painted the swastika on the wall of the Beth El Hebrew school. Oy.” The story was told by a Hebrew school teacher who was a survivor of Auschwitz. Of course I was the angry Epstein, and the teacher was really Rabbi Ben Zion Gold, who became head of Harvard Hillel in my sophomore year, he who was a death camp survivor. (There was an actual Epstein the butcher, extremely pious, one of my father’s clients, and his son was an exemplary student at the Beth El Hebrew School, leading the junior congregation’s prayers, whereas I was considered an idiot and the despair of my teachers.) The story of how I met Ben Gold after being estranged from Judaism when I entered Harvard and how he persisted in seeking a friendship with me and became one of my most important teachers is a separate essay. Neither can I omit Professor William Alfred, the playwright and Old and Middle English scholar, who was my thesis advisor. His stories of an Irish childhood in Brooklyn, raised by his grandmother who still lived in the world of Ireland in her head, drew me back to my own childhood at the lunch table at Kirkland House, where I was housed, and they were among the most important writing lessons of my time at Harvard. He talked about the Brooklyn Irish world of his grandmother, possibly his great-grandmother, and great-uncles so vividly that I turned back to think seriously about the world of my grandfather and great-grandmother. We would publish Bill’s incredible story of his father’s bigamy, his mother’s attempt to abort him by swallowing a cleaning fluid when she learned that he had another wife, only after Bill’s death. He in fact told me this story just months before he died. (To appreciate the shock of this, you have to know that not only was William Alfred an extremely pious Catholic but was also on the Cardinal’s lay advisory council in Boston. There was a sense of religious awe in Bill and a willingness to listen to students’ problems that drew one to him, and on the lecture platform he evoked Chaucer in the flesh, inhabiting the most outrageous characters, like the Pardoner selling bones as holy relics. In the end, it would be William Alfred who would get Thou Worm Jacob published, sending it to one of his students at Macmillan.

To return to Guerard, however, he called me into a conference in the fall semester, telling me how much he liked the story about “Epstein” and saying that he supposed I would take MacLeish’s class. “No,” I said. “He rejected me!” Guerard’s eyebrow raised in disbelief, and I became his disciple. Thou Worm Jacob was finished when I went to Stanford University, where Albert had accepted a chair for the year after I would graduate, and when my Fulbright to study directing in London under Joan Littlewood, fell through (Littlewood identified as a Communist, and the State Department not, I guess, unexpectedly blocked it) I took the Woodrow Wilson I had won to study at Stanford. That is another story, but Albert would guide my creative thesis at Stanford and help shape the manuscript that Macmillan accepted.

Now, to the “state of the Jews.” That was a familiar lament of many rabbis in the Conservative and Orthodox world of Judaism in the 1950s and 60s, as the American Jewish world became more and more assimilated and the American Jewish communities in the cities, where they clustered in neighborhoods and around synagogues, spread out into other ethnic communities and began to marry into other ethnic groups. “The state of the Jews” is a grandiose cliché which intelligent Jews shudder at. (One quote that I treasure is that of a fellow Pinsker, that tiny town in Belarus that was my father’s birthplace and which has exerted a strong pull on me since childhood, Weizmann another Pinsker, and the first President of the State of Israel, who dedicated his life to Zionism, but with the characteristic irony of a Pinsker, once quipped, “The Jewish people? A little people, but an ugly one.” It’s a bitter sense of humor, but paradoxically, a loving one.

In the middle of the 1960s, my father’s life, which had been centered both as a lawyer and a political figure, began to fall apart as the cohesive Jewish world that existed in two or three wards (electoral districts for election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives), our own, the largest ward with a Jewish majority, Ward 14, and a neighboring ward, began to lose their middle-class Jewish population. My father had catapulted, after a single term in the House, to chairman of the Committee on Education and with the support of the Governor, Paul Dever, and the Speaker of the House, Tip O’Neill (who would go on to be the House Speaker in the U.S. Congress) had secured a multi-million budget for the University of Massachusetts. He sponsored legislation that put women on Massachusetts juries, administered free polio shots, and saved Boston Teachers College by transferring it from the City of Boston to the State. I won’t go on here, but, as his son, it was hard to be only a B-plus student in public school and an idiot in Hebrew school. He never expected me to be able to duplicate his record, arriving in the United States as a refugee at 13 or so, not speaking a word of English, and going through one of the toughest schools in Massachusetts, Boston Public Latin, and then Harvard college, Harvard Las. He had been a Hebrew teacher to earn his way through college and law school. While he neglected my Hebrew education and never spoke to me in Yiddish, his first language, he did take me along as company in the car when we went out to look at the Amherst campus of the university, often asked me to come and meet him at the State House, watched him debate in the chamber, and I was a silent listener to his anger and frustration coming home from the legislature, disgusted by corruption and manipulation that thwarted his dreams. All of this fed into my imagination, and his ghost appears in many of my books. (One unpublished one is called The Boston Ghost.) The stories he told about his woebegone clients (he loved “characters,” especially the sad outcasts of the disappearing Yiddish world). He would often point them out to me as we went from one cafeteria in the district to another, shaking hands. Their stories, as he told them, were very funny and poignant, and he often took their cases and waived the fees for representing them. My mother would sigh, “He had done a million dollars of free law work.”) In my last semester at Harvard, at the end of my senior year, I was directing a large cast in Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist on the main stage of the new Loeb Theatre and was overwhelmed. I had to skip several of Albert Guerard’s workshops. Albert was furious with me, particularly when I handed in a sloppy manuscript that had none of the irony of the stories I had written in the first semester. His workshop required sixty pages of fiction. I called up my father, whose law office was only twenty minutes away in Boston from Harvard Square and with whom I had slowly built up a close rapport, particularly after I was accepted at Harvard (which he had despaired of): “Dad, come and repeat some of those stories about the characters you’ve talked about on Blue Hill Ave,” (a synonym for the Jewish streets of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan in Boston).

My father came into my room at Kirkland house on a hot April afternoon and sat in his vest opposite me while I typed up notes. We went from his stories about junkmen, electricians with broken hearts, and penniless cantors, to his own childhood in Pinsk when Belarus was a Russian territory, and his own father Israel’s flight to America, disappearing from his grandfather’s house when Dad was only five, leaving a daughter two and half years younger and his wife pregnant with a third. I was able to submit sixty pages. Albert was angry but impressed by what I had written. Happily, because when I went to Stanford and joined the M.A. in creative writing, Wallace Stegner, who ran the creative writing M.A., was not sympathetic. “I don’t know where you could go with this,” he said in his flat Western accent. (That was the first sixty pages that I had written at Harvard and that Albert had liked. When I submitted it two years later for a thesis, I was forced to remove the frame and send it in as a collection of stories. Yet it was a framed novel, unconsciously a parody of The Canterbury Tales with a dash of Gulliver’s Travels at the end. Albert, who was my thesis advisor, told me to just follow Stegner and Scowcroft’s suggestion to submit the thesis as a collection, but to circulate it to publishers as I had written it. (I wrestled over how to end the frame for weeks on end, and bang, I woke up one morning and had it—the horse!) The junkman and his horse was one of my father’s favorite anecdotes.

I had worked on this novel, which my editor at Macmillan and I decided to call Thou Worm Jacob, during the fall of 1962 in Cambridge, in the spring of 1963 during my six months of duty in the psychiatric division of the Air Force Medical reserve, and then in my first year of living in New York City, living on unemployment insurance of $28.00 a week, and trying to find work as an actor (I had an Equity union card earned during a summer of acting at the Woodstock playhouse and my father advised me that since I had served in the military as a reservist, I was entitled to unemployment insurance). When I came up against a brick wall as an actor, I was convinced to return to directing (that’s a long additional chapter.) An editor at Simon and Schuster who didn’t like the novel but had been at Harvard a few classes ahead of me recommended me for a fellowship at the Breadloaf Writing Program in Vermont. There, John Ciardi and Howard Nemerov, who heard a reading of it, gave it what was to my ears extravagant praise. They sent their appreciations to me, and I am sure that their words, together with William Alfred’s (who sent it on to a student of his), convinced the young editor at Macmillan to recommend it to a more senior editor, Richard Marek, who took it on. I was so disheartened at one point about it ever getting published that while visiting Bill Alfred (in 1964-65, Bill had supervised my undergraduate thesis) I threw the manuscript on the floor of his living room: “I just wasted my time!” I cried.

“No, no,” he said softly, bending down to retrieve the untitled manuscript from the carpet. “Let me send it on to a student of mine.”

And so…how has the “state of the Jews” changed? Well, in America, traditional Judaism has re-invented itself on the right and on the left. The sense of a threatened community that bound traditional, pious Jews to socialists who were not interested in religious texts or religious leaders and Zionists to whom the State of Israel was what mattered most. Altogether, the revival of Hebrew as a living language, the extension of Jewish settlement beyond a few towns, the emergence of farming communities and factories, and a growing population of Jews committed to living there despite the constraints were all miracles. After 1948, international recognitions and a Jewish state that could defend itself as well all seemed to promise that a tangible “state of the Jews” was alive and well, despite constant threats to its existence, even as the tide of assimilation of the large Jewish communities abroad, particularly in the United States, posed the question of how long it could maintain its identity. Phillip Roth and Bernard Malamud had made these questions vivid in their early fiction. The third of the trio, Saul Bellow, I was initially indifferent to, but in time realized he was the most searching. He was the only one who had a true command of Yiddish so that his translation of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Gimpel the Fool,” perhaps the latter’s best work, is a masterpiece of English as well. Bellow’s novel Herzog paints the Montreal Jewish world with a clarity that mesmerized me.

When I met Saul Bellow at a reception for the great Italian writer Primo Levi, whom we had published in Fiction before he was well-known in the English-speaking world, I complimented Bellow on his translation of “Gimpel.” I asked if he would translate any other work of Isaac Bashevis Singer for our magazine, Fiction. He smiled puckishly and remarked, “Singer fired me as his translator.” We both laughed.

I had first-hand experience of just how good Bellow’s translation was because Rabbi Ben Zion Gold had asked me to give a dramatic reading of it at a Jewish student dinner in my senior year at college. An audience of some 200 were in attendance. I was able to hold their attention for three-quarters of an hour—the prose, not just the plot, had an interior mystery and rhythm that was compelling, and I seemed to pass into the text.

As I look back over these lines, I realize that I have left out one of the most important influences on me: Cynthia Ozick. It’s bizarre, but in the spring of 1967, when Bill Alfred was teaching with me at Stanford in the Voice Project, he discovered Cynthia’s story, “The Pagan Rabbi,” which he chose for an anthology that George Plympton of The Paris Review edited under a grant from The National Endowment for the Humanities. Bill urged me to read it. I must have been jealous because I didn’t initially recognize how important it was, and that Cynthia had achieved in it what I wanted to achieve. I still keep teaching “The Pagan Rabbi” semester after semester in courses, and most of my students are just as intrigued as I am by the continual riddles it poses to the reader.

I can’t really speak on the “state of the Jews” but only about my own state of Judaism. My children puzzle me at times as to how much it means in their lives. My wife is Norwegian—she had an Orthodox conversion and joined me in an effort to keep a kosher home, observe the Sabbath, and involve herself, as I do, in Biblical and rabbinic scholarship. I was the beneficiary of the sense of mutual dependency among American Jews of the first generation that existed as I grew up in childhood and adolescence. I rebelled against it, mocked it to an extent, but slowly it asserted its hypnotism. I began to identify with modern Orthodoxy and take on what is called “the yoke of the kingdom.” I felt that if I was going to write not just about Jews but about my father and grandfather and their world, I had to experience it. In moments of absolute stress and hallucination, it bound me not only to ghosts, the ghost of my mother on the terror-filled night of her death, my father in his long grappling with his own mortality, but to a scholarly community that felt the same skepticism yet fascination that you identify in the narrative of Thou Worm Jacob. There is something both stiff-necked rigid in traditional Orthodoxy and naive and vulnerable.

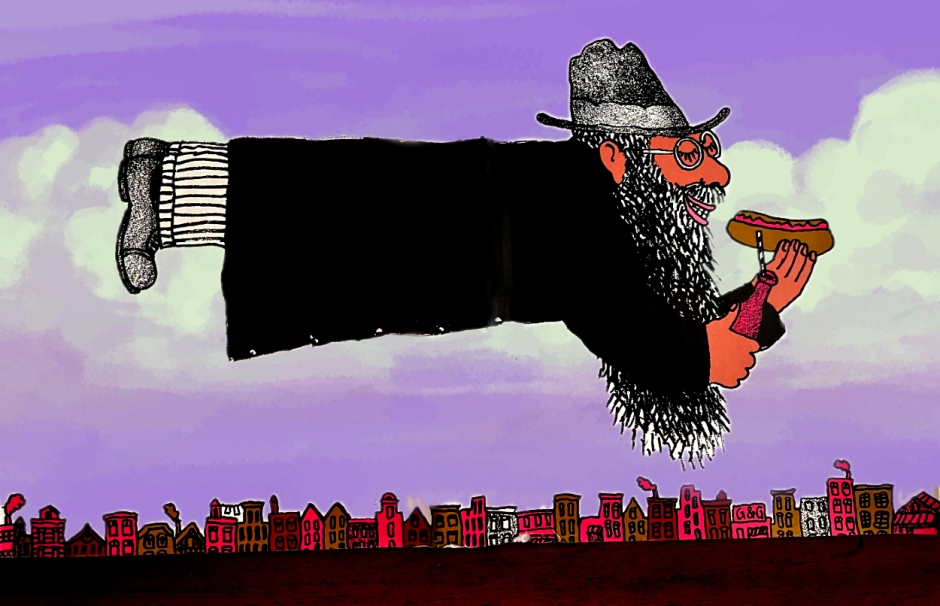

There is a story my father loved to tell about one of the characters who came once a year to our door when my father was in the legislature to ask for a charitable contribution to a Yeshiva or institution of study of the Talmud and other religious texts in Jerusalem. I never met this person, a meshulach or messenger, but I imagined him clearly from my father’s voice, dipping from his perfect Harvard English into the music of Yiddish and Hebrew. We would see, at rare times in Dorchester or Mattapan, someone dressed in the dusty black pants and jacket of an Eastern European Jew in Poland or Russia before the Second World War, with a bent back, a straggling disheveled beard, often a strange hat, on the main avenue or one of the poorer streets. Such a sight is familiar now in Brooklyn, Manhattan, where a strict dress code has set a large community of traditional Jews apart from their fellow believers. My father was raised in a traditional household, educated by an extremely pious grandfather, and reunited with his father in Boston, encountering the best and the worst in Boston’s Jewish religious world. Dad was certainly a skeptic, identified as an agnostic, but he had a deep background in rabbinic learning, often quoted the Talmud, and met these “characters” who seem to emerge from a mysterious fog to ring our doorbell with relish. The Meshulach having waved his charity box under my father’s nose, and receiving a larger packet of dollars than he had a right to expect, paused, and rather than turning and hurrying away, looked up at my father, “Mister Mirsky, I have for you a shylar.”

A “shylar” my father explained to me, is an important question of law, on which only a rabbi who is a good or great scholar can give a correct answer.

Sighing, the Meshulach bent toward my father’s ear, and in a hushed whisper, asked, “This Kennedy, is guht tsu deh Yidden?”

Whatever narrow world this old man collecting for a far-off yeshivah lived in, he was worried about what the new President, Kennedy, would mean for the Jews. It may sound very parochial, but what my father heard was that sense of a mutual community of concern.

Here I have to insert on Wednesday, November 2023, in the wake of the massacres, kidnappings, and horrors, inflicted by Hamas in the South of Israel, and the bombings of Hezbollah in the North, to mention with grief as well the bombings that have cost civilian lives in Gaza, and the nightmare of a resurgent anti-Semitism throughout the world, that the Meshulach’s question is not quaint. It is no longer a voice from a lost European ghetto existence or from the world of the Holocaust. As I wrote last week to you, George Salis, “It struck me as I lay anxiously in bed last night, reviewing the latest news of nightmare from the Gaza Strip and the Lebanese Border and in fact across the world that the irony of ‘the State of the Jews’ is horrifyingly alive again…the old, shabby messenger, the ‘Meshulach’ at father’s door, was prophetic in asking his question.”

I live in an assimilated world. My wife assimilated into an Orthodox Jewish world with a lot of courage, but I also assimilated into her Norwegian world, fascinated by it. My children are certainly assimilated despite their years of school before college at Ramaz, a modern Orthodox Yeshiva. A lot of what asserts itself in the media as Jewish culture seems to me trivial, and what is happening now in Israel, a place which I have visited, brought my children and wife to, and taught a short semester at, have become attached to, is so upsetting that I feel a deep pessimism about where the “state of the Jews” to pun on both meanings, is headed. I was beaten as a child by Irish bullies from a neighboring street for “killing Jesus,” yet when I visited Ireland, it seemed like a second home, and as a boy of three and four, I was aware that if the United States lost the war, we would be murdered as Jews. Living with that anxiety as a child has made me strangely hopeful.

I break off because there is so much more to say, and what most interests me in your question lies in details that I can’t explore within this format. Thou Worm Jacob was followed by a much more shaped novel, Blue Hill Avenue, which returned to the same terrain. I tried again in The Secret Table in a novella, Dorchester Home and Garden, to go back to a devastated burnout, but it did not seem to touch most readers, though in thumbing through early reviews, I discovered one that did fall in love with that novella. The other novella in the collection, Onan’s Child, really touched the reviewer in The New York Sunday Times, who thought it might replace the original text (which is a one-liner in Genesis but has spawned an endless series of books and religious speculation, including the whole of the Zohar, the foundational text of Kabbalah). Onan’s Child was the first fruit of my fascination with the biblical narrative and an attempt to follow a character into a story of his or her own. At the same time, when I went out to teach at Stanford University in 1966-67, I finally began to read the Babylonian Talmud and its storehouse of such stories. It happened when I found myself, in the late summer of 1966, arriving early in Palo Alto to teach in Jack Hawkes’ Voice Project at Stanford, with the time and permission to roam its stacks. There was the Soncino Talmud, overwhelming if you just plunged into it without a teacher, but I went to its index and found an entry that went on for pages and pages under the word “Death.” I started to explore and began to madly copy specific references whose narrative and language rang in my ear like a bell summoning me to attention into a notebook.

It was a terrible bell, though, for a year later, just at the same moment, my mother would hear her death sentence and die six months later.

I wrote yet a further novel about Boston, Puddingstone, which, after years of frustration with publishers and constant editing (including removing forty pages, painfully, after Donald Barthelme drew a pencil through them and told me to “cut”), my son helped me to self-publish. It drew wonderful appreciations from Cynthia Ozick, Joseph McElroy, and other friends, but without the power of national distribution and reviews, it sandbagged and escaped any national or even local attention. My friends at The Boston Globe were dead or retired, and despite the fact that this satire on Boston politics, Messianism, was my answer to the “state of the Jews,” at least in 2010, it is a well-kept secret.

It occurs to me that I may have left an impression of myself as more pious than I am. In writing about my father, my grandfather, my Jewish identity, my pleasure in Hebrew, rabbinic scholarship, the Talmud’s stories and mysteries, I’ve painted myself as living according to the strict laws of Modern Orthodoxy rather than confused, constantly wrestling with a sense of temptation, yielding to it, frightened by myself, and restless. One of the most interesting of medieval rabbis, the Rabad, was characterized by his contemporaries, in a biblical phrase, “a pot ever on the boil, or seething pot.” In the last few years, as an escape from the present reality of the United States, Israel, Europe, and the world’s political turmoil, I have taken shelter in another culture, in particular, the romantic videos and tales of ghosts and crime streamed over the internet from Korea. I felt at first an innocence in them, as well as the threat of North Korea hovering over their culture, as well as a problematic past. In the last few weeks I have been watching one that was evidently very popular when it was issued: Alchemy of Souls (I keep thinking of it as Anatomy of Souls), which grew on me as I felt its eerie evocation of the world of paganism with its vivid portraits of evil and death, the human will to try to escape it by imagining a personal power in the space of the heavens, the stars, but more accurately in a world beyond our own, or our consciousness beyond life, what we think of as death. The vain hope to evade death is the theme of Gilgamesh, its reality is that of the Odyssey, Dante’s Commedia, and the sub-text of Kafka’s The Trial. Rabbinic Judaism promises an elaborate escape based on a few lines of the very late biblical book of Daniel that Christianity, as it is recorded in the Gospels, embraced. The Five Books of Moses refuse to let us imagine another world and force us to trust this one, and surprisingly, one of the first rabbinic codes, the Mishnah, repeats this warning. In the novel I published with Sun & Moon, The Red Adam, based not only on Kabbalah but the brilliant scholarly work of Gershom Scholem in Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, who influenced many other writers, and particularly Borges, I cite those lines: Whosoever speculates upon four things, a pity for him! He is as though he had not come into the world, [to wit], what is above, what is beneath, what before, what after. (The Mishnah, Haggigah, 2:13). Of course, the writer is the pitiful scribe who takes that curse upon himself, herself. I remember in Rio de Janeiro, touching on the subject of evil as Scholem traced it in the mystical texts of rabbinic Judaism at a small reception, with the Brazilian authoress, Clarice Lispector, and her stepping into the middle of the room, her considerable body shaking as she cried out, “Eevil, oh Mark, I so want to doo, eeevil!” And how I have savored anew each time I re-read Cynthia Ozick’s “The Pagan Rabbi” how she evokes the sexual rapture of Greek mythology and its forbidden terrain.

GS: Your novels are humorous and satirical. In your debut, Thou Worm Jacob (1967), a moyhel and cantor employ a kosher skepticism to steal food from women, and then there’s a circumcised horse who joins a minyan. Have you experienced any backlash from religious readers? And on that note, do you believe some things are sacred—beyond humor, as it were—or should anything be up for grabs?

MJM: Well, of course there was a backlash. Both in Boston and in the network of “approved” experts on what is Jewish and what is not. In Boston, Thou Worm Jacob was a best-seller; it got rave reviews. Jonathan Kozol gave it a wonderful notice in The Boston Globe. Kozol had been a student of Albert Guerard’s, and we became friends after he visited one of Albert’s seminars. We began to sit together in front of the wide glass windows of the Hayes Bickford, a 24-hour cafeteria, in the fall of 1962 when I returned from my year at Stanford, staring at the Radcliffe women and the students from other schools drawn to Harvard Square. I didn’t get to sit there long as my father, without telling me, signed me up for a job as a substitute teacher. I was waiting for an opening in a reserve unit. Since I got out of graduate school, I was subject to the draft. I went off grumbling to teach history at one of the toughest schools in the grim shadows of the elevated Girls’ High in Roxbury but found that I loved teaching these young women from the poorer streets of Boston, African-American, working-class Irish. When they realized I enjoyed their rebellious precociousness and were happy to argue back, it forced me to find ways to make American history dramatic. I urged Kozol to try it, and that was the beginning of his real career and his book, Death at an Early Age: The Destruction of the Hearts and Minds of Negro Children in the Boston Public Schools (1967).

Seymour Simckes, author of Seven Days of Mourning, who came from the same streets as I did and is a lifetime friend, reviewed my debut novel for another Boston paper. Simckes was also indirectly a teacher of mine, alert to the hidden laughter of the Talmud, and a master of interpreting Kafka’s mischievous sense of humor in pain. But the most surprising mention was by Francis Russell, a total stranger to me. He was a dyed-in-the-wool Yankee but a truly radical one, a conservative who concealed an anarchist’s heart, descended from governors of Massachusetts. Francis had lived in Mattapan as a young boy before the beginning of the First World War, when the Jews began to flood into Dorchester and Mattapan. He had observed what had been a Yankee preserve, Wellington Hill. He was an expert on the Stearns family, his neighbors in Mattapan, the family of T. S. Eliot’s mother, and in a wonderful book about Mattapan’s change into Jewish streets, from 1910 to 1930, he was fascinated by the new arrivals. His review, “The Magician of Mattapan,” praised me in The Christian Science Monitor, comparing me to Isaac Bashevis Singer. Francis noted all the landscape details I had dotted my pages with, like the iron pikes fencing off the Mattapan State Asylum for the Insane along Harvard Street in Thou Worm. I wrote him a note of appreciation, and we became life-long friends.

As for the experts, Irving Howe, who had been my teacher at Stanford during my year of courses there and whose lectures on Huckleberry Finn were inspiring, was not impressed by Thou Worm Jacob. As his graduate student, Irving let me interrupt his remarks on Twain’s masterpiece with my own thoughts, for one of our weekly classes and a half of another. (We had an on-and-off friendship, recognizing our common Jewish background. I sold him my bicycle when I bought my first motorcycle in Palo Alto with my bar-mitzvah savings, but I committed a terrible error regarding a buxom, very appealing graduate student, a young woman from the South, whose nickname “Babs” seems to speak the aura that followed in her wake. I was unaware that Howe was dating her and foolishly talked about what I found attractive about her and what put me off. I got a terrible scolding from him. We were driving in his new red convertible (which superseded his purchase of my humble bicycle) when I mentioned what I found elusive in her beauty. “Don’t you ever talk about a woman that way!” he barked, interrupting our easy back-and-forth.)

Several years later, after Thou Worm was published, he told me to my face when we met on Cape Cod that he didn’t like my book. (I found that very painful, as he had rescued me at a dangerous moment in my year as an M.A. student at Stanford, forcing me to laugh at myself when I was wandering around the Stanford campus close to a nervous breakdown. A friend in Cambridge had just called to tell me that my girlfriend at Radcliffe was sleeping with someone I previously thought of as a friend. Howe took me for a cup of coffee and let me tell my story, chiding me out of my self-pity.) Despite my amusement at why he had barked at me, I thought of him as a sarcastic but wiser older brother, and at the table that day on the Stanford campus, he discretely shared some of his own romantic disillusions. I remember his sigh and final remark, “The older you are, the harder you fall,” like the worldly wisdom of Koheleth (Ecclesiastes). I hoped I would get to know him better when we were both back in Manhattan.

Howe’s anthology A Treasury of Yiddish Stories, edited with Irving Greenberg, which Rabbi Ben-Zion Gold had given me, had opened up the “brave old world” of my father and grandfather in Eastern Europe. Yet he kept me at a distance whenever we met back in New York City. The World of Our Fathers, which catapulted Irving to national fame, was wonderful but it was solely about the world of Jewish socialism and distorted the world of the Jewish immigration, the thousands of little synagogues, the serious Talmudic study, the intellectual life that religious scholars brought to the United States, in fact, The World of My Fathers. In an essay I read of his, Howe flippantly referred to this with a choice Yiddish expression that said, in essence, “When you don’t know anything about something, keep your mouth shut.” That I felt was too easy. Like Bernard Malamud, in an interview I did for the Jewish student journal at Harvard, Mosaic, replying to my question, “Why do you write about Jews?”

“Because they are rich in culture.”

That seemed like an evasion. I knew it was brash of me to press him, but that was part of what I carried away from Harvard and Stanford, a sense that I could criticize. “You speak however of Jewish identity as magical, in your story, “The Lady of the Lake,” it’s the key to the heartbreak there and has nothing to do with “culture.”

Malamud terminated the interview with the quip, “The answers are all in my books,” and basically threw me out the door. We would, in fact, become close in a wary sort of way in the course of time. Howe, however, grew more and more sarcastic when our paths crossed. (When Cynthia Ozick, in front of a large audience at YIVO, in their old Fifth Avenue mansion, referred to me as a “mystic,” Howe sniggered loudly, “You, Mirsky, a mystic?” This condescension was very painful since I respected him and we had points of agreement. For instance, his singling out the two stories, “The Man Who Studied Yoga” and “The Time of Her Time,” in Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself, as among Norman’s best fiction. When Open Admission sent a tide of unprepared students into City College and threatened to destroy it as a major institution of education on par with Harvard and Yale, I tried to brief Howe on the chaos I was experiencing in the classroom. I was on the factory floor, so to speak, and as a socialist, I thought he should know what was actually all happening on a campus where he had been an undergraduate. Howe was at the Graduate Center now, insulated from all of this in the Ivory Tower that the Chancellor, Bowker had created, ensconced in a reduced schedule and doctoral classes with choicer students. Howe, standing in those elegant corridors, airily dismissed my complaints. After that lofty wave, I abandoned any hope of being close to him.

To go back to the reviews of Thou Worm Jacob, The New York Sunday Times called on a low-level Jewish reviewer who edited popular collections of recognized Jewish writers. He loathed the book and dismissed it. Commentary published a wholesale rejection of the book by Robert Alter. Alter was a friend of Ben-Zion Gold who thought highly of him, but I understood that I would always get the cold shoulder from Commentary and its circle of reviewers. (Later, when I had absorbed Umberto Cassuto’s brilliant commentaries on the Hebrew Bible and went back to read Alter, I found his condescension to Cassuto unsettling, and as I gained a sense of insights from scholars who were doing genuine research into the linguistic background of the texts, whom I had become close to, I was less impressed by his translations. and the way others toadied to him—yet I also admired his commentary and helped bring him as a speaker to The Museum at Eldridge Street where I was on the Board of Directors. I don’t know if he remembered me but his handshake was so limp that I suspected so.) There were other good reviews around the United States, not just in Boston. Maureen Howard in The Partisan Review, one of the major intellectual journals, gave it an enthusiastic response, and that was a joy.

Alfred Kazin, another one of the Jewish gatekeepers with Irving Howe, whose words were taken as absolute law as to who was worth reading, who wasn’t, used to prowl around the lower East Side. It was still intensely Jewish, housing many of the Yiddish-speaking survivors of the Holocaust in the 1960s, their restaurants, businesses, etc. (It was rumored that his walks there were not necessarily sentimental but that he was looking for romantic partners among the droves of young attractive women who populated its streets in the early sixties. Graduates of the Ivy League college, art students, and dancers from across the world, lured by the inexpensive apartments and the presence of other unmarried young men and women.) I kept bumping into friends from my college on Avenue A, B, and First Avenue. Many of the older Jewish, Italian, Ukrainian men and women were evacuating to the suburbs, and there was an abundance of rent-controlled flats. I bumped into Kazin on the corner of my street, East 13th and A, recognizing him. I had enjoyed his book, A Walker in the City. I asked why he hadn’t mentioned me or any of the other younger Jewish writers in his reviews.

“You think too much about yourself, Mirsky,” he snapped. Later, at a party at Robert and Jean Lifton’s Manhattan apartment, I was in the room close to Kazin when he called out to Norman Mailer as the latter passed by him, “How’s the great American pig?” (Norman had published An American Dream recently—which must have been what Kazin was referring to.) From the expression on Kazin’s face, he obviously thought he was being funny.

I knew Norman from summers in Provincetown, was a witness to fights between him and Adele in the months before he stabbed her, had watched him go from amiability to uncontrollable fury, his good-humored face contracting into an ogre’s. Mailer began to advance toward Kazin as if to kill him, possibly to drag Kazin toward an open window just behind him. (We were at least ten floors above the street.) Everyone in the room knew about Mailer stabbing his wife, Adele, a few years before. Kazin’s’ face crumpled, but his wife got behind her husband, screaming. Norman’s wife, Beverly, may have intervened too. After a tense minute or two, Norman backed off, Kazin slinked away, and the party resumed.

I have many stories about Norman, and the three of his wives, Adele, Beverly, and Norris, I got to meet. At one point, he asked me to collaborate on a script for The Deer Park, and toward the end of his life, he invited me to several dinners at his house with Norris. I had a number of conversations with him that taught me a lot, and I felt privileged to have known him. There was a bond between the two of us which was real though unspoken that grew over time—I always saw him, even in our first meeting in the summer of 1960, as an older Jewish kid from Brooklyn despite his bravura as Hemingway’s successor. His wife Adele had aspirations as an actress and got a minor role in a production at the Playhouse where I was playing the lead in several of the plays that season, Major Melody in Eugene O’Neil’s A Touch of the Poet. I was surprised to find, some years after I had met him, that he was fluent in Yiddish. It was during a Signet banquet. The Signet was the Arts & Literature club at Harvard, to which T. S. Eliot and Theodore Roosevelt had belonged. George Plympton had wangled a central hall at The Metropolitan Museum of Arts for the occasion and was the Master of Ceremonies. After Plympton’s very clever opening remarks and the substantial supper, I found myself in the room dedicated to the elaborate steel, head-to-foot, jousting armor of the 15th- and 16th-century knights, with Mailer, E.J. Kahn, and one more luminary. The three of them started speaking in rapid Yiddish to each other, laughing uproariously, while I stood by dumbfounded. Several times during our friendship I asked Norman if he would write about his Brooklyn childhood because every now and then he would talk about it and was not just funny but making fun of himself. I had met both of his parents, who were steeped in the world of Yiddishkeit.

One story that I did not appreciate at the time was what Norman sent when my editor at Macmillan, Richard Marek, solicited a blurb for the jacket of Thou Worm Jacob. That book is so distant from anything Mailer wrote or would write (apart from his The Gospel According to the Son, which I think is Mailer’s unappreciated masterpiece. Frank Kermode alone seemed to recognize its deft attention to the prose of King James in The New York Sunday Times—a review Wikipedia studiously ignores in its evaluation of Mailer’s career). I didn’t know Mailer as well in 1967 as I would later, and would never have asked him to respond to a book that I knew had nothing to do with the worlds he was exploring. I admired Advertisements for Myself and it was part of my education as a young writer. His conversation at the Old Colony in the front window’s big table had drawn me back every afternoon in the summer of 1960 from rehearsals at the Provincetown Playhouse when I could sneak away. I would squeeze into a seat at his table to listen to him hold forth. Three years later, I was in Provincetown as a director at the Playhouse, and I got to know him better. Mailer did write back to Marek with a blurb, permitting him to show it to reviewers but forbidding its use on the book jacket or in any publicity: “Mark Mirsky has more talent than most people have hairs in their nose.” In 1967, my nostrils felt flagellated by barbed wires by this. In retrospect, I treasure its prick as a pinch of true affection for me. As I got to know Norman better, I saw the ingenue behind the bully in his character.

Anyway, although put down in The New York Sunday Times, nevertheless in Boston, San Francisco, even Texas, reviewers loved my book. There were of course people in the Jewish streets of the greater Boston world who resented its unflattering portrait of a dying Jewish world and wrote to me, or my father, complaining it was getting a lot of local attention and the letters of outrage tickled me. Looking back, the language at times must have been challenging as I wove lines of Isaiah and some of the intonations of Yiddish into the book’s English. Donald Barthelme, who could be extremely harsh in his criticism and who, like Mailer, was writing about a very different world than mine, was sometimes sympathetic to vulnerable friends of his for whom he felt empathy. When I teased Barthelme about the blurb he had bestowed on the novel of a close friend of ours, a book I knew Donald could not possibly have admired, he replied, with the smile of the Cheshire Cat, “He’s learning to write novels, by writing one.” I was doing that in Thou Worm Jacob.

And yes, in fiction, “everything is up for grabs.” The biblical books delight in this, and if you read between the lines of the Talmud, there are many instances of this comedy, but without a sense of humor, you will not hear it. I would often surprise pious and impious Jewish students, whose knowledge of the rabbis was gleaned only from their studies at conventional Orthodox schools, with quotes I had come across in my frequent wanderings through the Soncino translation of the Babylonian Talmud.

GS: This may sound like a contradiction in terms, but it seems as though humorous novels aren’t taken as seriously as other types of novels. However, I think humor can often heighten tragedy and other serious matters. What are your thoughts on this? I should also note that, compared to your debut, your third novel has a higher concentration of tragedy alongside the humor, such as an orphan girl who is abused by her adoptive parents and a Rabbi’s pupil who is enlisted into the Korean War and later goes missing, presumed dead.

MJM: Of course, laughter is the sign of real tragedy. It’s a cliché of directors working in the theater that you rehearse a comedy with a cast of actors in rehearsal by stressing its tears, and a tragedy, by finding its laughter. Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels was one of my guides, the outrageous as the dead serious, and its horses provided the ending for Thou Worm Jacob. When It came to Blue Hill Avenue, its genesis was a story the novelist Seymour Simckes had told me about a mother who kept calling his father, a rabbi who lived just a few streets away from us, and a friend of our family. Rabbi Simckes was the very soul of sweetness, but as the book took shape, some of my own savagery and my father’s experiences began to color the character of Rabbi Lux. Only the reviewer in Buenos Aires caught on to the parody of Alice in Wonderland—Rabbi Lux going down his toilet bowl in the grim shingled three-deckers of a run-down Dorchester street rather than a rabbit hole in an English garden. Lewis Carrol mingled with the prophet Isaiah, Borsht Belt Yiddish humor, and a cast of political figures that some Bostonians could identify. The editor asked me to cut one of the most brutal moments in Thou Worm Jacob, realizing that it might endanger the book’s reception and sales to libraries. It is the threat of a local undertaker, who was part of the corrupt political machine in the Jewish streets, to cut off a voter’s balls and stick them in his mouth in the coffin if the man didn’t vote for his candidate. This was just one of my father’s colorful anecdotes of the darker side of the Jewish streets. As a lawyer and political figure, he knew just whose five-and-dime variety or hardware store was a front for the numbers racket or a bookie. He had endless wry tales about the warm handshake with the Italian Mafia, the overarching Irish political control of Boston, the power of the Yankee bankers. I realized after Thou Worm was published that I had made a mistake in agreeing to cut that anecdote about the undertaker. The passage echoed another in the novel, and its structure was weakened by its excision. Fanny Howe, the poet and novelist who has been a constant friend, published the excised pages in a little magazine she edited called Fire Exit. There it waits for someone to republish Thou Worm and restore it to the book. As for the tragedies in Blue Hill Avenue, they were all real; my father’s law practice and his stories of the real life of the Jewish streets were a hypnotizing bitter encyclopedia of hypocrisy, leavened by his laughter that I tried to memorize.

You can read part two of my interview with Mark Jay Mirsky here.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Listen to a discussion of Thou Worm Jacob between George Salis and Jacob Pascoe on The Collidescope Podcast:

Mark Jay Mirsky, professor of English at The City College of New York, published his first novel, Thou Worm Jacob, in 1967, succeeded by Proceedings of the Rabble in 1971, Blue Hill Avenue in 1972, and a collection of short novellas and stories, The Secret Table, in 1975 with a cover by Donald Barthelme. In 1977, Mirsky published My Search for the Messiah, a collection of essays including sketches of major Jewish thinkers: Harry Wolfson, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, and Gershom Scholem. His novel, The Red Adam, was published in 1990, The 252 Absent Shakespeare appeared in 1995, followed by Dante Eros and Kabbalah in 2003, a sketch of the poet, Robert Creeley, Creeley, Pressed Wafer in 2007, and a play Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard produced at the Fringe Festival in NYC, 2007. The Drama in Shakespeare’s Sonnets, A Satire to Decay, was published in 2011. In 2014, Mirsky’s novel Puddingstone appeared, and in 2016, a memoir of Ruth S. Mirsky, A Mother’s Steps. Works he has edited include Rabbinic Fantasies—an anthology co-edited with David Stern in 1990, The Diaries of Robert Musil (1998), The Jews of Pinsk, Volume 1: 1506–1880, in 2008, and Volume 2: 1881–1941, in 2013. He’s a founder and editor of Fiction Magazine.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

2 thoughts on “The Yoke of the Kingdom: An Interview With Mark Jay Mirsky – Part 1”