You can read part one of my interview with Mark Jay Mirsky here.

GS: How would you compare Hebrew and/or Yiddish with the English language? Also, what are some of your favorite Hebrew or Yiddish words?

MJM: I don’t really know modern Hebrew, though there is enough biblical Hebrew in it so that, while watching Israeli films, I catch a lot of the laughter in the dialogue. Mastering biblical Hebrew has been a lifelong effort of mine. After a disastrous seven years in six-year Hebrew schools that met after public school hours in Boston, I abandoned hope for a number of years and felt a failure in my father’s eyes in that regard. I am not sure why he suddenly took hold of my Jewish education to prepare me for my bar-mitzvah, but he made me feel the emotions of the prophet Isaiah in the passage I had to sing, and he was surprised that I responded to his instruction. After that, we got along better, but he didn’t resume any direct instruction in Hebrew.

Here, again, the story is too complex for this space. I warned him that I was not going on to Hebrew High School if he expected me to take on the Boston Latin School. The Hebrew High School was, I think, desperate for students, so it wasn’t hard to get in, but I knew the Hebrew was just flying over my head. (My sister went and did splendidly there. She inherited my father’s aptitude for languages.) Instead, my father and I began to talk about philosophy and the mathematician Alfred North Whitehead, and my father and I began to develop a mutual respect as I absorbed his conversation. He would drive me to Latin School in the morning while I read to him from a book of Winston Churchill’s early memories. When I was just shy of sixteen, I began driving him while he read to me. In turning away from Hebrew, though, and the family’s respect for Jewish scholarship, I knew I had betrayed both my grandfather and my great-grandfather, whom I am named for, Moses or Maishe Mirsky. Maishe was a step above a rabbi, a religious judge, a man respected in Pinsk both for his scholarship and his piety. The burden of this history and my failure to live up to it still weighs on me. Happily, at Harvard, I met Rabbi Ben Zion Gold, who began to ply me with books that explained my father and grandfather’s respect for rabbinic tradition and also introduced me to Yiddish literature in translation. I suddenly heard all the voices that were present in my childhood and many of the characters whose doubles trooped through the doors of our house in Dorchester and then in Mattapan, many of them characters who, in retrospect, seem to have tiptoed out of the stories of the great Yiddish writers: Sholom Aleichem, Peretz, I.B. Singer, Bergelson, Chaim Grade. Rabbi Ben Gold was a close friend all through college, graduate school, my employment at City College, Stanford, and when in Cambridge, I went to his services at Harvard’s Hillel. When I was stumped by a puzzling remark by Rabbi Soloveitchik in a lecture, I went to Ben to try to unravel it, and he would spend hours with me until he had come up with its source both in the Talmud and the Hebrew Bible and amaze me with his radical translation of its Hebrew source, in language that rendered the Hebrew text direct and naked. It was a Hebrew so sexual that I realized how far the elegant English of the King James had strayed from the source. In my later years, the friendship of the biblical scholar Edward Greenstein, his brilliant introduction and translation of The Book of Job, his many essays on the Bible and the literature of the ancient Middle East have been invaluable, as well as the lectures of Rabbi Jeremy Rosen, who has become a valued teacher to me. His background spans both the ultra-right Mir Yeshiva and a degree from Cambridge. Despite my struggles with Hebrew, I discovered a passion for the text of the Hebrew Bible and its rabbinic commentaries. And more distantly, but looming over me, the lectures which I attended as regularly as I could after my father brought me to one by Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, and that amazing scholar of Jewish mysticism, to whom, ironically, Max and Marianne Frisch introduced me to: Gershom Scholem. Finally, the man Ben Zion-Gold told me was the “greatest Talmudic scholar of the 20th century,” so I burned with curiosity to read and possibly to meet him: Saul Lieberman. Our bond lay in the tiny satellite village of Motelle, just outside my father, grandfather, and great-grandfather’s city, Pinsk, whose two-volume history I would find myself editing.

You asked me about Hebrew and Yiddish. In regard to the latter, I could tell a number of anecdotes, how I once disarmed a rather ferocious Israeli, a high administrator at City College in my brief tenure as chair of the English Department with the store of Yiddish expressions I employed to comment on my colleagues in a frank discussion. I must have picked them up as an adolescent in the Jewish streets of Boston. They describe different categories of fools and idiots. Many are based on the male organ: shmuck, shl’meel, shnook, potz, shmendrick—all of them are open to interpretation, but anyone of them can start a fistfight. (Puppik in my family meant tummy, but in the Yiddish-speaking world of a friend, who is fluent in Hebrew and Yiddish, a mathematician with an international reputation, it evidently referred to the penis.) My ear is attuned to Yiddish, so when I stumble upon a new one in a book, I add it to my vocabulary. (There is a juicy one in Bellow’s Herzog.) My mother inherited a few chaste ones from her mother and passed them on frequently, teaching by repetition: my groisseh lappen, “my big spoon,” when we reached for a portion beyond what we could eat at the table. “Don’t chock my chaiynik” means “keep nagging me, banging on my head as if it is an iron kettle.” The word for rags, shmutties, described an article of clothing so torn it went into the family ragbag. But when one of my mother’s older sisters or brothers asked at a wedding, when she showed up in a dress she had worn before, “Why are you dressed in that shmutty?” she was devastated. (They let my father know as well—since before her marriage, according to an aunt, she had been known for her impeccable dressing.) The music of self-mockery is often chirping in Yiddish, though, and it depends on how you take it —the Jewish power brokers of the New York Fashion industry mock their influence, referring to trade in the Garment District as being in “shmutties.” One Yiddish phrase I learned from my father’s sister, Aunt Sonya, after my father’s death, I often employ since I often spill out my thoughts without thinking of their effect, Affen lung, affen tung, which means “It’s turning in your chest, it jumps out of your mouth,” and though this trait appalls my wife and daughter, alas, I can’t easily repress my thoughts. Yiddish was my father’s first language, but he never spoke it in our house. I lost a valuable inheritance as a result. Once, though, driving together, I remarked of some disaster, “I need that like a hole in the head,” and he shouted at me, offended by the lame English, “Like a lochen kop, a lochen kop!” the car swerving as he banged on the driver’s wheel.

What binds Yiddish to Hebrew is their common sense of humor, and words pass freely from one to the other. In the Bible, David flees into a Philistine city but immediately realizes he is among his enemies and starts acting crazy or meshuggeh. It is reported to the Philistine king, who doesn’t kill David but ejects him with the cry, “Don’t I have enough meshuggehs?” In English, into which the word has passed, it implies not insanity as such but someone who is more than just annoying (that is, a nudnik) but who’s annoying, confused, stupid, and crazy on top of it. The rabbinic commentators are geniuses at discovering puns and double meanings in Hebrew and are not above undermining a reputation. My father loved to quote Rashi, a medieval French rabbi, and his sardonic comment on the line in Genesis, “And Noah was pious in his generation.” “Yes,” Rashi agrees, “But what a generation!”

I could go on and on, for I love Yiddish and Hebrew, but though it is well past midnight as I write this, I would be remiss if I did not mention three of my instructors whose work changed my life, whose books, lectures, my interviews with them, drew me deep into the Jewish past. I spoke about them at length in my early book, My Search for the Messiah, where the reader can find much more detailed accounts of Harry Wolfson, Gershom Scholem, and Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik. I have briefly mentioned Rabbi Soloveitchik, who was known in Orthodox circles as the “Rav,” or teacher. In the nightmare and anxiety that I found myself after my mother’s early death, I asked my father to take me to hear the one rabbi in Boston he had always spoken of with respect, even awe, Rabbi Soloveitchik, and whom he told me had been very close to his father, Israel. I was surprised to discover that not only could I follow what were three- and four-hour lectures on the biblical text read that week in the synagogue, but I was also swept up in the drama that Soloveitchik projected. I was elated when I walked out of the lecture hall in Brookline after dazzling lectures which flung me into my grandfather and great-grandfathers’ worlds and into the spheres of philosophy and science, dizzy with what I had grasped. When I went on my own, after that first lecture, to hear the Rav lecture again and returned to my father’s room, he asked me to repeat what I had heard, and I could see in his eyes as I echoed some of the remarks and arguments of the Rav with enthusiasm, a sense that I had linked myself to his father, my grandfather, and my great grandfather, who had taught my father in his boyhood. I seemed quickly to master much of the Hebrew and Aramaic terminology and to hear what few in the room seemed to register, the laughter in the Rav’s remarks.

At the same time, after my mother’s death, I picked up a book Ben-Zion Gold gave me when I was twenty-one and just graduated Harvard, Gershom Scholem’s Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. I could not go beyond the first few pages then, but later, I flew through the chapters and became Scholem’s disciple. Many years later, in an eerie moment, Scholem’s books would bring me into a deep conversation with Jorge Luis Borges in a crowded room where Borges was being celebrated. I had met him before, in New York City, and in Buenos Aires, but now he drew me close when I went up to introduce myself, and for twenty minutes, ignoring others, he spoke passionately with me about Scholem, Kipling, the mingling of the erotic and the mystical. I had met with Scholem and his wife three times in Jerusalem and once in Zurich at a small dinner hosted by Max and Marianne Frisch at a restaurant whose menu and décor were remarkable. Picassos and the work of other famous painters were on its walls, but I hardly registered them as Scholem performed while I observed Max’s reactions to what was a brilliant but authoritarian monologue. A dinner that is worth a chapter of its own—but alas, not here.

Kafka speaks about the book being the axe that breaks up the frozen sea within us, and these men’s books did so for me—my thoughts flowed into theirs and theirs into mine. The most unexpected one was Professor Harry Austryn Wolfson’s, which, like the world of Rav’s and Scholem’s, I thought was beyond my capacity to understand. He had been my father’s freshman tutor at Harvard, and my father spoke of him with awe because Wolfson knew thirty-six languages and was a graduate of the Slobokda Yeshiva, the Yale of Eastern Europe. As the greatest Jewish scholar alive, he was the ultimate authority figure for my father, and if, as it was rumored, Wolfson was lax about keeping kosher, my father could make an exception as well. I had never attempted to read Wolfson as I assumed that his staggering erudition was beyond my ken. I was summoned to his office after I wrote a number of articles about the Jewish world of Boston that were published in The Boston Globe. I hid from this Wolfson through my years at college, afraid of being interrogated, slouching behind my father whenever by chance we met Wolfson, a tiny but intense figure whose broad head loomed over the body of a five- or six-year-old in our walks through Harvard Square. Dad called me in New York City to tell me that Wolfson wanted to speak with me.

Astounded (it was as if the Pope had summoned a young lapsed Catholic to Rome), I took the train up to Cambridge within the week. In person, I found him both witty and charming. I met three times with Wolfson in his office at Widener Library over the next few months. I immediately immersed myself in his work. His book on Spinoza renewed my thirst for classical philosophy, dampened by a boring course on Plato in my freshman year at college. My father’s favorite philosopher was Spinoza. Wolfson’s portrait of the Dutch Jew who was excommunicated, a rebel who drew on Jewish sources for his challenge both to philosophy and to religious tradition, was dramatic and compelling. I could understand how he had shaped my father’s agnosticism. Still, I also saw how Wolfson drew out the contradictions in Spinoza’s logic, how Spinoza re-inserted his faith in the survival of memory as an echo of Kierkegaard and contemporary existential philosophy that, inevitably, as he tried to understand the universe, he took a leap of faith which had no basis in his meticulous logic. I went on to Wolfson’s volumes on Philo and rifled through his pages on the Church Fathers and the Islamic Kalaam. It was, however, Wolfson’s short volume, Religious Philosophy, where I hear unmistakably the sharp but homely Jewish wit that whistled through the crowded bookshelves of his office. I return to its pages again and again and copy them for students in whom religious belief is an important part of their lives. Wolfson talked about his work to me as if we were fellow authors and friends. He had a very strong Yiddish accent, which one could not have guessed from his balanced and elegant prose. If one listened carefully, though, there was mischief and irony afoot, bringing together Jesus on the cross and the founder of Rabbinic Judaism, Yochanan ben Zakkai, on his deathbed—another example in which my father’s brilliant graduate of the Yale of Eastern Europe used the Church Fathers as his proof text in the arguments for faith in the promise of the afterlife.

“I am a poet too,” he whispered to me at one point as he bent over the galleys of one of his volumes, pointing out a line, and again, that dry whisper, when he had the galleys of his book on Philo spread out on the table before, and I heard at my ear as his finger came down on the scroll, “You think Philo wrote that?” And then a dry, barely audible chuckle, “I wrote that.”

I was amazed at Wolfson’s dignifying whatever he had read of mine with this comparison, but I did find in his work just that sense of language that characterizes poetry, riddles, and epigrams as a means of expression. When I came to read Dante for a second and third time in my early thirties, it was Wolfson’s essay “Immortality and Resurrection” that gave me the key to understanding what I believe Dante was seeking in the Commedia. Without it, I could never have gone into the cantos of the Purgatorio and Paradiso without losing my way.

Looking back, I doubt I would have finished or even embarked on my volume Dante, Eros, and Kabbalah without Harry Wolfson, but equally it would have been impossible without Gershom Scholem and the radical moments of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s lectures. All three tested the limits of what we can understand from the texts of the past that explain something of the world we experience today.

GS: Can you talk about Donald Barthleme, Max Frisch, and the start of Fiction Magazine? How has the publication changed over the years? The author bio in your third novel, Blue Hill Avenue (1972), refers to Fiction as a “newspaper of stories,” for instance.

MJM: This is not one question but four, each one of them a lengthy essay or small book to speak of adequately. A long time ago, TriQuarterly 43 published a long piece by me on the founding of Fiction. There are lots of details in it, but I don’t want to repeat what I wrote there. Donald was still alive, so I didn’t mention a number of piquant moments or lay bare some of the struggles back and forth. Later, I wrote about Donald in McSweeney’s 24, but I tried to avoid repeating material from the narrative essay about him that I began just after his death (a death that could possibly have been avoided or at least delayed if he had gotten the proper medical attention).

One amusing detail, not so funny at the moment, was that Donald, sipping his perpetual comfort, a bottle of Scotch, as he laid out the first issue of Fiction at the compositor’s in a back room, spilled his drink over the layout boards and had to redo them all. Donald, though, put an immense amount of time into the issue, soliciting pieces, collecting art, investing his own money in the printing, unasked for, finding not only literary contributors but figures in the art world like Tom Hess, whose foundation gave us a substantial sum. Friends of mine also contributed once that first issue was published, and they saw what Donald, I, Max, Marianne Frisch, and Jane Delynn had done. As I review them today, the graphics were even more fantastic than I thought at the time. The joke on the cover, Marcel Proust wallpaper in the background with the old print of the sleepy Big Bad Wolf in bed decked in Grandma’s hood, and a seductive but suspicious Little Red Riding and the gigantic phallic cactus surrounded by three demure maidens, illustrated Donald’s story, “Three,” a bitter but mischievous fairy tale of his own life as so many of his stories are. In this case, it pointed at Max Frisch, who was published in that very first issue of Fiction.

I was deeply upset by Donald’s passing. When I confessed the melancholy that I couldn’t let go of in its wake, my wife said to me, “It’s because you loved him.” I have loved other writers, but Donald let me come close to him in a way over the years that no other writer has. The last time I saw him, I had no idea how ill he was. He had just returned from a year at the American Academy in Rome, and his wife, Marion, and their child stopped for a few days, possibly weeks, at his apartment on East 11th Street, between Sixth and Seventh Avenues. My wife and I went over to have drinks with him and Marion, but I could feel something was wrong. Donald was waspish and talked about going through his papers and correspondence, trying to sort them. It didn’t sound ominous, but now I think he was anticipating a disaster. As I replay that final moment of sitting with him, Marion, Donald’s wife, and my wife, Inger, whom he had trained to take over the design and layout of Fiction, I recall how bitter he was about his life. He disparaged the riddle of his identity as a man. Inger and I were both shocked that he would express it while sitting next to Marion, who adored him. We dismissed it as late afternoon blues after an exhausting return from Rome and having to contemplate flying on to Texas. Now I realize that the intuition of death was in his bones, though he would insert a final joke in his saga on his death bed, one that made me weep with laughter.

I tried to capture some of his whimsical humor and the complex innocence that he exposed to me in a long article that I wrote and rewrote. In a way, I felt inadequate to the task. Roger Angell, his editor at The New Yorker, I thought knew him better and was the one to memorialize him. Though when I asked Roger to come up to City College and talk about Donald, it seemed that I knew Donald far more intimately than Roger did, despite the very strong bond between them. It may be, though, that Roger, in front of an audience of students, academics, and a few members of the public, was reluctant to reveal secrets. Talking about how much editing the New Yorker had to do on Cheever’s short stories, he remarked on how clean Donald’s was. (I had witnessed Donald’s extreme editing when writing a story, but Roger wasn’t aware of it.) I did send my essay to The American Scholar, and the editor there sent back a curt note saying she didn’t think Barthelme was important enough to include in the magazine. That infuriated me, and of course, when the Daughtry biography came out of Barthelme’s life, Hiding Man, it was reviewed in almost all the major journals and media. It may have sold more copies than Donald’s books. It was very good when Daughtry described Donald’s teaching, but he didn’t really understand Donald’s stories or novels, yet neither did most of the reviewers, so they let that part of the book pass without comment. Karen Kennerly, who dated Donald at one point, was one of Daughtry’s sources. She told him about Miles Davis’s put-down of Donald when Karen arranged for the great Jazz musician Miles Davis to meet Donald at Elaine’s, the famous East Side restaurant where the fashionable world of fame gathered. (Karen had rented an apartment from Miles and was close to him.) I had heard the story firsthand from Karen. Their evening (all three at the table) was hilarious and painful in the same breath; she really caught the clash of egos and Miles’ cruel teasing of Donald, who was used to dominating in a clash of wits but whose admiration of Miles and his position as a white boy put him at a disadvantage. As Daughtry retells it, all the fizz of laughter goes out of the clash. The bubbling of Karen’s voice, as I heard it from her, took a certain pleasure in Donald’s humiliation that evening. The anecdote, alas, was reduced to stale champagne in the biography.

Despite Donald’s reputation and the prestige of his regular appearances in The New Yorker, his sales did not pay back his advances, I was told. When I first met him, he pointed to his chinos. “That’s all I need, and a few shirts.” He talked about keeping his expenses to a minimum so as not to go out into the world to teach for a living. (The first time I asked if he would come up to 139th Street and teach at City College since I had the ear of the Chairman and Dean, he replied, “When my brain is sufficiently deteriorated by alcohol….”)

Roger Straus would finally refuse to renew Donald’s contract, and he left Farrar, Straus and Giroux for Putnam’s, where Faith Sale, who was first our copy editor at Fiction but had gone on from copy-editing and reviewing to become a senior editor there, rescued him for a time with a large advance. Roger and his wife, Dorothea, whom I was very fond of, came to our house for dinner occasionally, and we went to theirs. I told Roger when he told me that he had sold the rights to all the books of Donald’s that Farrar, Straus had published, “You’ve made a mistake.” I still think so, not necessarily financially but in terms of the firm’s reputation. Dorothea Straus, who was very fond of Donald and his work, was distressed as well at the breach between her husband’s firm and Donald. This is all gossip, though.

If I want to come to the founding of Fiction, I have to go further back than April 1972, when we published the first issue. Bear with me. Only my recent affection for all the digressions in Sterne’s Tristram Shandy gives me the courage for such a long diversion.

In my freshman year at college, I saw a young Radcliffe freshman crossing Massachusetts Avenue, a woman who dazzled me but in whose eyes I saw so much pain that, maddened as I was at that time by the novels of Dostoyevsky, I fell down on my knees before she reached the curb, crying, “Natasha Pavlovna, I love you.” Momentarily, I took on the persona of Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. I was drunk on my new identity. I had actually been accepted at Harvard, though I was only a B student at Boston Public Latin, shining only fitfully in its English, History, and Latin classes, depending on the teacher, or “master,” but mediocre in Greek, Latin (after the first year), mathematics, and French. The sole distinction on my record was the gold and silver medals for declamation, which called upon my acting skills. At Harvard, even as a freshman, I quickly played major roles in Harvard’s theatrical community. That behavior spilled into my pretentious or absurd behavior on the street. I couldn’t keep that up for more than a moment, but it caught this Radcliffe freshman, Judith, off guard. And she did have a world of pain in her eyes and expression. I managed a few sane words, and we became friends of a sort. She already had the body of a mature woman. It was painful to look at her because I realized she was beyond my reach, but very smart, and, as I got to know her, genuinely distressed. In terms of life experience, I was light years behind her. It was like a four-year-old falling in love with his beautiful, twenty-four-year-old mother. She dropped out of school by the end of her freshman year, went to New York, worked as a model, dated graduates of Harvard that I knew, and was briefly the girlfriend of a novelist I got to know when I moved to Manhattan, Rudy Wurlitzer. From one of her girlfriends at Radcliffe, Anne, to whom I am still close and with whom she corresponded, I learned that she had been incarcerated in a mental institution in Connecticut by her father after he lured her back from Manhattan to Cincinnati. I wrote to her at that institution. She wrote back sharp, funny letters. I learned that she had been released after a few years and had gone back to college in Cincinnati, Ohio. Despite a number of new romances in that interval, we exchanged letters, and when I was in Alabama, then Florida, during the last four months of my training in the Air Force reserve, after breaking up with another Radcliffe girl the year before and without having found anyone else to attach to, I decided to drive up on my motorcycle from Montgomery, Alabama to Cincinnati and propose marriage. I rode through a day, then into the night without stopping, driven by some dybbuk, hoping to cross the Ohio River by morning. At times, I caught sight of a railroad track through the trees and heard the horns of an approaching train, not a smooth one of the 1950s, but one of those old steam whistle trains with its interlocking gears exposed, and it rolled on, its route running through the same valley as my highway north. The train itself gained on me, and I caught sight of it for a moment, illuminated by the moonlight as I sped onto the bleats of this relic of the 1930s, churning its wheels and gears on the tracks beside me as the road dipped and rose among the hills of Tennessee and Kentucky. Its whistle died away in the forest—there were few lights along this lonely highway, and the world around me was silent, interrupted only now and then by a small town, a gas station still open. But then I would hear a whistle—another train, as its lost music had come to accompany me as I pushed forward in an impossible dream. When I finally clattered over an old railroad bridge with a narrow lane for cars into Cincinnati and found the suburb where she lived and her father’s house on a hilltop, Judith put me up for the night but also informed me that she was engaged to a young Englishman, Cyril. He was staying with her. Her fiancée had begun to make his fortune, and it was obvious within minutes of meeting Cyril later that day that he was the appropriate candidate.

The dream rescued me from some of the self-pity that had trailed me after my break-up by telephone at Stanford with a girl in Cambridge, and with friendly hugs both for Judy and Cyril, I got back on my motorcycle but caused a multi-car crash in a tunnel in Pennsylvania driving in and out of a drenching rain that kept loosening the motorcycle’s chain. The rain followed me from the edge of Ohio into Pennsylvania and New Jersey, where I stopped to dry out at my father’s sister’s home in Teaneck, but I made it safely back to Boston, greeting my mother and father. Dad was running for a political office he could never win, a seat on the Boston City Council. The council members were elected on a city-wide basis, not by district, and it was a solid Irish council with a single Italian exception since there were just enough Italian votes to get one seat. I knew it was hopeless, my mother knew it was hopeless, and I knew I had to flee to New York City, where an agent had written to say she wanted to represent me after hearing about my successes in Provincetown and Woodstock. Just as I was preparing to leave, however, Albert Guerard called me. He was at Tufts University at a conference on changing the English curriculum in high school and college, funded by the U.S. Department of Education. He knew that I had taught high school English and thought I would find it interesting. “Can you come out to it?” he asked.

Desperate to see him again, feeling lost, “Sure,” I said. Borrowing my father’s car, I drove out to Somerville and took a seat in the hall. I listened to a number of famous professors and educators, such as Walter Ong, a Jesuit priest, and Jacqueline Webster, President of one of the Catholic colleges. It was spearheaded by a professor from MIT who had famously rewritten the high school math curriculum. John Hawkes, Guerard’s disciple, was there as one of the organizers of the conference. None of them had any experience teaching high school English or high school subjects like history or any idea of how to involve students in thinking creatively about literature, history, or sociology, let alone reading texts or writing in response to them. After an hour in which most of what I heard was jargon, bored, and a bit angry, I jumped up without an invitation since I didn’t see anyone paying attention to being recognized by the organizers before they spoke, and asked in a loud voice, “What are you talking about? How many of you have been in a high school class to teach? I have heard a lot of interesting vocabulary but not a single proposal about how to get these students involved so that they care about literature or history?”

I was remembering my first few days in Girls High, when, as I tried to teach the famous Marbury v. Madison case, a tough African American teenager, probably sixteen, but already a mature woman, shouted at me, “Why should I care about Marbury-Madison?

I had to reply or lose the class and called back, “You’re here because of Marbury versus Madison. Because eventually the Supreme Court did what was right and ordered an end to segregation in the schools.” And I felt the class, both the African-American and the Irish students, lean forward in their seats, surprised by the passion in my voice for the first time—engaged.

Guerard was nervous at first. He loved rebels, but I had been a loose cannon at Stanford, stomping about in motorcycle boots, letting my photograph in a vested suit (from my freshman year at Harvard when I tried briefly to dress like an octogenarian professor) appear in The Stanford Daily, with my Phi Beta Kappa key, dangling in sight, to mock the President of the Student Council who was advertised in a similar photograph in The San Francisco Chronicle as reading it daily. It was his first semester teaching at Stanford, and he knew that others were wary of the way his endowed seat had been set up by David Packard of Hewlett Packard in memory of Albert’s father, Guerard Senior. (Albert would get over his anxiety after the first few months, but that’s another story.) At Tufts, however, evidently others at the conference were impressed by my outburst, and Albert hurried to tell me that they wanted me to join the conference, which was to meet a number of times. It paid $100 a day, and all your meals, and hotel rooms, as well as transportation. (My unemployment insurance payments, when I went down to Manhattan in a few weeks, was about $22.50 a week based on the meager amount paid to an Airman third class during reserve duty. I was entitled to draw from it for six months. It went up to $28.00 when I claimed it again after leaving American Heritage a year later. My monthly rent in two cramped rooms with a large walk-in closet, toilet, bathtub, and sink in the first room [I had to provide a small refrigerator later as well as an electric plate for cooking] was about $29.00.) The $100 was a massive subsidy at a moment when I was regularly running out of money for meals between checks.

There were three memorable conferences after the one at Tufts, one in New Orleans, where I met men who spoke with real genius on the subject of education: Gerald Holton, a physicist at Harvard, and Ben de Mott of Amherst, a critic of national education, and a third I think was at Columbia. It was there that I met Donald Barthelme. It was focused on literature, and there was a star-studded cast of writers and critics in attendance aside from Guerard and Hawkes, including Susan Sontag and John Barth.

I could go on for many paragraphs about that conference, but it was Donald I seemed to focus most on, despite all the distractions. We sat in a rectangle with a central aisle and a sort of platform at the top of the room. Donald sat across the aisle from me, so he was in plain view. He listened intently, but all the while, no matter who the speaker was, this bemused smile played over his lips, projecting an eerie authority into the room. “What is he thinking?” I kept wondering. I don’t remember exchanging a single word with him during the two or three days the gathering went on. John Barth, whom I would learn Donald admired, got up, his tall body towering over everyone around him. Barth was on my side of the room, and every now and then, I swung around from my fixation on Donald to look at him a few seats ahead, but there was no smile or scorn, just a blank stare—and later when I read his novel, The End of the Road, it seemed as if he had been at that moment the personification of its protagonist, Jacob Horner, a shadow of a devil because of what seems to be an unshakeable lack of affect. Barth got up after the morning session without saying a word or speaking to anyone and evidently went back home because I didn’t see him again at the conference, but his silence and absence after the morning session spoke volumes.

I will break off here, only to resume the founding of Fiction when I reach Musil and his influence on me and introduce Max and Marianne Frisch. Their presence in New York City as we put together the first issue made a great difference.

GS: What is a novel you’ve read and think deserves more readers? Why?

MJM: Of course, Musil’s The Man Without Qualities ranks high on my list—his novel is as important as Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Kafka’s The Trial, and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. You have to work your way through Musil’s work, starting with the early short stories, and try to enter a strange world where politics and sexual awareness give way to a spiritual eroticism. I don’t want to say more since your next question asks me to be specific about Musil.

While I love almost everything of Virginia Woolf’s and try to teach The Lighthouse, which is certainly not neglected, as often as I can, I think the critics are not fair to her earlier novel, Night and Day. It is often dismissed, but its parody of Jane Austen, its insight into how one becomes the person whom someone who loves you imagines you are, always touches me.

Right now, Onetti’s novel, which Suzanne Jill Levine translated many chapters of in Fiction, has no American publisher. Suzanne says that it his best and I loved what I read. Camilo José Cela’s Family of Pascal Duarte, an early novel, is another masterpiece that I doubt most Americans know. John Donatich discovered Musil’s Diaries through the publication of extracts of it in Fiction. When Manuel Puig was basically booted out of his American publisher, we became friends since I loved his work and had reviewed Heartbreak Tango in The Washington Post‘s Book World, which meant that the review was covered in the International Herald Tribune and the old liberal New York Post. It was I who found him a publisher for The Kiss of the Spider Woman, which led to movies and a Broadway production. I published several extracts of his books, but the first two, Betrayed by Rita Hayworth and Heartbreak Tango, remain my favorites.

GS: You edited Robert Musil’s Diaries in the late 90s. Can you tell me more about this project? Would you say Musil’s diary entries are as intriguing as Kafka’s, for instance? In general, can you reflect on Musil’s work and what you admire about it?

MJM: I am currently working on an essay linking the journals of Thoreau, Kafka, and Musil (my present preoccupation with your questions has interrupted it). There, I hope to explore the strange correspondence between the journals of all three of these writers. I admire all three. Musil is much more direct in what he exposes but not necessarily in his diaries, which were private. Like Kafka, he exposed himself in his fiction, but he went beyond the boundaries that Kafka set for himself. Thoreau did not write fiction as such, but the journals that he mined for his books are full of revealing lines and anecdotes. Sometimes, I find his most radical insights in his journals; at other times, he exposes himself in his published work, like Kafka and Musil. Rabbinical scholars argue that Maimonides only let readers who could read between the lines glimpse his secret thoughts. In that sense, Modernism and Antiquity, Albert Guerard’s critical insight that an author always reveals himself in his work, and The Book of Job as Edward Greenstein reads it in a new translation published by Yale University Press, agree. Scholem told me when I first met him in Jerusalem to read Leo Strauss’s Persecution and the Art of Writing, and when I met him the next time, he asked almost immediately, did you read Persecution and the Art of Writing? To my shame, I had not, but when after his death I did, the shock of recognition set me back. Strauss had anticipated my book Dante, Eros, and Kabbalah as I searched for the secret of why Dante had written the Commedia.

You asked about Musil, though, and I will try to reflect on it and explain why I admire him so much. Let me go back to my discovery of Musil. There are authors who are invested in myth, and even a very young reader is influenced by this. When I was a boy of twelve, thirteen, and fourteen, Kafka was considered as I understood the world of adult literature (Proust and Joyce were not in my limited circle of references), one of the most difficult modern authors to understand. I got hold of the selected short stories and was struck by “The Metamorphosis.” I had begun to tear at my face, complicating a very bad case of adolescent acne, and so the idea of turning into a cockroach and being swept out the door was eerily familiar. It also helped that I liked to tease people, and particularly girls, as my sexual energies began to surge, as I watched other boys hypnotize girls of their own age and younger. At the same time, I got so anxious on Saturday afternoons before the boys in a club we had formed went to house parties or dances at the local YMHA (Young Man’s Hebrew Society) that I began to squeeze what I thought were blemishes in my complexion staring at the mirror in our bathroom in the mid-afternoon so that, by the time arrived to go out, my face was an angry mess, which I tried to coat with various medications. I went to them seething with anger and felt that if there was a God in the universe, it was an unfair one, personally hostile to me. I was a monster, but in terms of courting a girl of my own age or a few years younger, I was an idiot. Girls grew up very quickly in that lower-middle-class Jewish world and began thinking of marriage at fifteen, and they were aware of themselves as desirable objects. I didn’t really understand Kafka, but I felt a kinship with his character, who is turned into a sort of hopeless bug. “Do you believe in God?” I would burst out to a girl on the dance floor at the YMHA, which was an impersonal whirl of couples. I would get a look of surprise, but before she could hurry away, I would add, “I don’t. If there is a God, let him strike me down right here!”

It gave me some crazy pleasure to evoke the horrified reaction of a girl who was barely a teenager. Musil first won my complete attention in his journals when he scares a young singer and dancer, performing nightly in a tavern, who would probably have become his mistress if he pursued her. She is living a life between that of a performer and a potential prostitute, which leaves her vulnerable. He invites her to dinner after watching her troupe perform, and as he walks her home afterward, he hints that he may be the serial murderer who has been killing women like her locally. He is making her aware of him. Sartre will write a story like this in Nausea, a far less playful voice, where “awareness,” the goal of existentialism, dominates the plot. Musil calls himself Monsieur Le Vivesecteur, but one quickly discovers he is practicing that medical procedure on himself.

I distinctly remember lying on Nantasket Beach reading Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” at fifteen or sixteen, possibly for the second time, trying to understand it. One of the girls in a bathing suit that already displayed a mature woman’s figure, probably about my age but at least half a foot taller, paused at the blanket tossed over the hot sand where I was absorbed in the story and asked what I was reading. I looked up, with Kafka’s story in my face, intent on breaking through the superficial conversation I knew she expected from me and contracting it into the expression I had memorized from Olivier’s portrait of Richard the Third, which was streamed over the television, stared with as evil and mocking a smile as I could manage, “About a man who turns into a cockroach.”

She scurried away, leaving behind her polite, slightly condescending curiosity and possibly pity. What I wanted, of course, was attention, hers, and some sort of challenge so that I could explain myself. Later, I would read Dostoyevsky and find similar portraits, and I would find young women who were sympathetic to them. Somewhere in my junior year, I found them, not in the streets of Dorchester or Mattapan but in the suburbs, Newton, Wellesley, Cambridge, and there, at Harvard, more intense liaisons as I grew older. I learned to listen. I lost my atheism; however, shortly after, I lost something precious at the end of my sophomore year at the college and went through a genuine health crisis that summer. I was forced to my knees in the sands of Provincetown and surrendered my solipsism. I was not the center of the universe. I was small, helpless, and begged to be cured, and I was, but I understood that I could no longer rail at the Heavens with confidence.

Under their often bitter skepticism, there is a stubborn religious belief in the three authors I have mentioned. Musil’s wrestling with the uncanny in his life is the most intense, for he did not despair of entering another dimension of existence and tried to enter it. So did Kafka and Thoreau, but Musil’s imagination as he set it down in his fiction comes closest to my own dream life. I had heard about him vaguely from some of the undergraduates at the college who were fluent in German. Neither Albert, who taught his contemporary, Thomas Mann, nor anyone else in the English Department at Harvard seemed to know about him. Edmund Wilson talked about Kafka, though he seemed to miss the latter’s sense of humor. I never took a formal class on Thoreau or Emerson; I just discovered them on my own. I found James Joyce on my own as well, but during my year at Stanford, Albert taught Proust, Joyce, and Gide, I think, but it wasn’t until Max and Marianne Frisch arrived in Manhattan somewhere late in the fall of 1971 or the winter of 1972 that Musil’s importance was impressed on me. A strange tension ran through that issue that I was unaware of until later.

Marianne was Donald’s translator. Her enthusiasm both for Barthelme’s work and for Musil knew no bounds—since Donald and I were gathering materials for the first issue, and Marianna was interested in everyone who knew him, gathering information about him, she quickly drew me into her charmed circle. There were thirty years between Max and his beautiful wife, Marianna. Donald was nine years older than Marianna, but she and I were about the same age. I had no idea about who Max Frisch was when I met them. It was only after a small dinner with Borges and Max and Marianne, along with other New York City literary finaglers (it was she who invited me to join them at the Georg Rey after Borges spoke at Columbia) that Max’s genius dawned on me. I hadn’t read any of his work, and at our first meetings, seeing him puff on his pipe in Donald’s living room while Marianna did most of the talking, he seemed like a sweet European gentleman, someone’s grandfather, not one of the major figures of European literature, whose reputation spanned Switzerland, Austria, West Germany, and East Germany as well, for Brecht had been a close friend. After the dinner (a chapter unto itself again), seated next to Max, directly opposite Borges, I ran out to read all of Max’s fiction I could find. The Frischs were a bridge to the world of European literature—they knew a number of Nobel Prize winners, including Samuel Beckett and Haldor Laxness.

To return, though, to one of your questions about Musil, whether his diary entries are as intriguing as Kafka’s, a subject that I want to explore in detail: Musil was ruthless in talking in his journals about his sexual life but even more so in his fiction. There, his wife was his collaborator. Kafka, in the new translation by Ross Benjamin, is strikingly open, but he practices extreme discretion apart from several passages about prostitutes, but when it comes to the women to whom he proposed marriage, he buries them in ambiguity, and only a novelist will dare to interpret his code. This is even more so for Thoreau.

GS: Your latest novel is Puddingstone: Franklin Park (2014). It was your first new novel in about 25 years. Can you talk about that gap in novel writing and what it was like to return to the art form?

MJM: Just below, I list all the fiction I wrote after the publication of The Red Adam in that 25-year gap. Douglas Messerli had promised to publish Puddingstone. He even selected one of my wife Inger’s colored linocuts for the cover. He had run a number of black and white ones in the pages of The Red Adam. He had promised to bring out The Red Adam in hardback, which might have secured it a review in The New York Times, but it never happened, and though he announced Puddingstone in his catalogue, he never set it in type but just delayed and delayed. It went on for years. I began to give up hope, and through an agent, I did get an advance from him, but even that didn’t result in its publication. Finally, I asked the agent to resecure the rights to it.

I never left the novel as an art form. It was the publishing industry and the small press world that left me. In the vast space between Sun and Moon’s publication of The Red Adam, several novels were on my desk that went nowhere, The Boston Ghost, The Face of the Ocean, and most recently Dream Castle. The one I am working on now is a response to Tristram Shandy, egged on by Calvino’s praise of it as a “post-modern” novel. Suddenly, at the age of 79 or 80 years of age, the book opened up to me—previously, I could not get past the first twenty pages or so.

Douglas Messerli lost interest in me—shortly after that, he lost all interest in Sun and Moon. Sad, because he did a very elegant printing of The Red Adam.

[Editor’s note: Shortly after publishing the second half of this interview, Douglas Messerli sent me an email. With his permission, and in the interest of providing both sides of a story, I’ve decided to share his words: “There is always another reality to all such viewpoints. I never lost interest in or love for Mark’s work, I just didn’t have money, having already spent far more from our (my husband Howard and my) personal savings than I should have had if we wanted to survive into old age (still an issue for us). I COULDN’T publish Mark’s book and others I had committed to, not because I didn’t love or had lost interest in their works. My engagement with the writing was there at all times, but the financial means became impossible. Somehow writers never comprehended that I had created such a great press with no money at all, simply moving from one book to another with the hopes that I might still continue. And miraculously I kept going on and on, unbelievably for years until finally I realized if I continued Howard and I would be totally bankrupt of our small savings we retained. I was selfish for the writers, not for myself, and never once took a salary or possible financial reward from the press. It was always all about the writers, some of whom, to this very day, never understood that I was without money to support their books, not without intense love of their writing. It’s so painful to hear writers, to this very day, describe my inability to publish their works as a disinterest in their writing. NO. NO. I was broke. That’s it! I created a press that never had any financial substance behind it—yet it lasted for years because of my imagination that it might survive. That it did, and I published so much important work should never be misunderstood as lack of love for the writers I published. I was an impassioned crazy man, who cared more about those than he could ultimately commit to. It was a lie of love. Love that I couldn’t continue to pay for. Few bothered to realize I was the one with the broken heart, the empty pocketbook. The serious writer in the corner who people thought was the big spender. How to take a date out to dinner when you can’t ever pay for the bill? I was a lover without a wallet. My failure was that I loved too many men and women and cared for them in ways that the general culture could never. I thought simply that my love and attention, my gift of publication, might be enough. But given the world we live in, of course, it was a ridiculously pointless idealism. I was deluded, a fool. But I still have no regrets, and the love I felt for my writers has never ceased. And then I remember. Look, we published all these wonderful books that might never otherwise have seen the light of day. I did what others didn’t dare to, and I’ve joyfully lived with the consequences.”]

I haven’t even bothered sending out the novella Frackenstein that I wrote after Dream Castle. Some of the shorter novellas I wrote I published in Fiction, The College Magician, for instance, and The Brooklyn Golem, since it was conceived as a place where we all who were contributing could share work that did not immediately find a place in the world of commercial publishing. Also, I began to write in imitation of Borges and his master, Unamuno, books that pretended to be academic but were, in fact, dream explorations of other writers’ work. I began with several plays of Shakespeare in The Absent Shakespeare, a riposte to Borges’ story “Everything and Nothing,” which was followed by The Drama in Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

I had a long tussle with Syracuse University Press, but at last, they did print my Dante, Eros, and Kabbalah, which is an imaginative understanding of the secrets Dante was concealing in his Commedia. These books all have scrupulously academic footnotes, but they certainly enraged or tickled the usual scholarly experts. Albert Guerard understood what I was doing and wrote loving appreciations. So did Cynthia Ozick. The book followed Guerard’s insistence that in almost every important work of fiction, a writer is writing about himself or herself, struggling with the riddles that personal experience imposes. To find that struggle is to join the author in what Emerson called “creative reading.” If you follow Italo Calvino in If on a winter’s night a traveler, he inhabits other authors’ styles, parodying them, mocking himself, but with a genius that is uniquely his own and, like Barthelme’s voice and style, impossible to imitate. (It was Donald who directed me to Calvino.)

GS: What have you been working on lately?

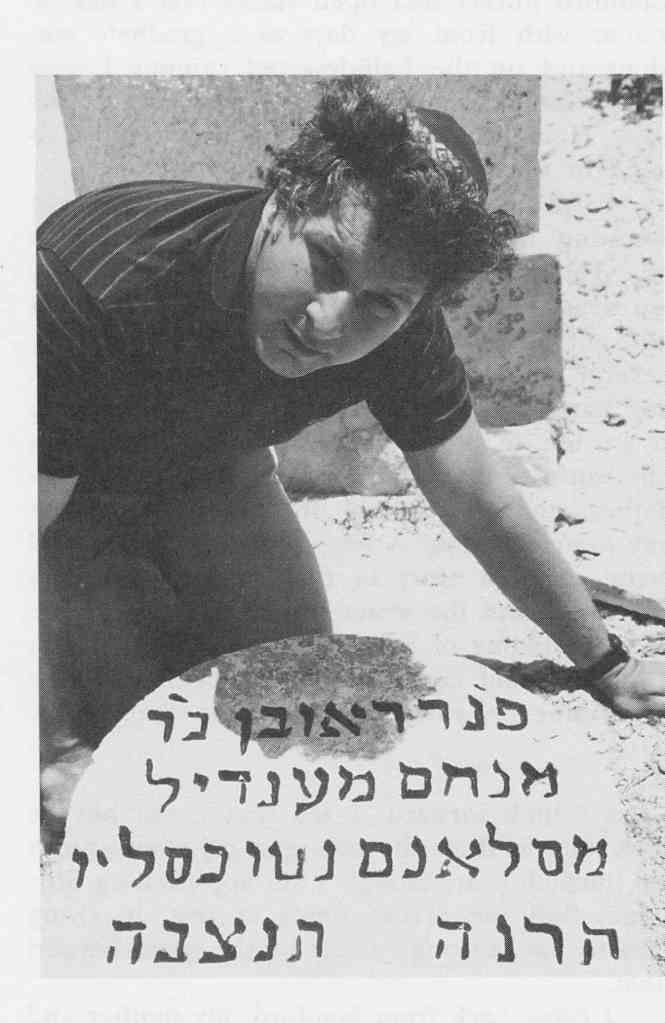

MJM: It’s embarrassing, but there are several novels that I have written but have not found a publisher for. Only graduate students and some friends have read them. There is always the chance that they may come out of the desk drawer; some of Melville’s did. The furthest back is called The Boston Ghost. After that, there is one called The Face of The Ocean. Jason Trask, one of my most talented former students and a close friend, likes it, and so do I—it is anchored in the Massachusetts coast and the interior of Maine. The most recent one, which my agent hasn’t found any takers for but which both Jed Perl, whom I deeply respect, and Fanny Howe were enthusiastic about, is tentatively called The Dream Castle. It runs 561 double-spaced pages. After that, I wrote that novella based on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, her circle, the poets Byron, Shelley, and Byron’s amuensis, Polidori. It is also a tale of a frustrated professor who falls in love with a student and exchanges bodies with her. I haven’t even sent that out to anyone but one student who was shocked by it. I am still working on a book about my father and his family and the traumas they experienced both in Eastern Europe and when they came to The United States. The National Endowment for the Humanities funded its writing, and it was the basis for the two volumes I edited on the history of my father’s city, Pinsk, published by Stanford University Press.

I was finally able to read Tristram Shandy at the age of 80 after three or four earlier attempts beginning with my year at Stanford when I read A Sentimental Journey by Lawrence Sterne, delighted in it but was baffled, even annoyed, trying Tristram Shandy and unable to go more than a few pages before feeling hopeless as it made no sense. Now, though, I’ve pickled myself in its pages and read as much as I could find about Lawrence Sterne so as to follow Italo Calvino in appreciating Tristram as the forerunner of the post-modernist novel. Just as I did in reading the Commedia but in a less academic, more personal manner, I have tried as a novelist to enter the strange worlds of fantasists before me—Burton’s translation of A Thousand Nights and One, the Talmudic sages, the rabbinic commentators, Mary Shelly—who reflect my own. Now, I am trying to interpret the mysteries that Sterne left us and to turn them into an examination of my riddles.

GS: From the title Thou Worm Jacob to a moment in Blue Hill Avenue that also invokes man’s vermicular condition, do you find yourself possessing some degree of misanthropy?

MJM: Absolutely, I believe I descended a grade below Jonathan Swift and his uplifting of the horse as superior to humanity. The phrase “Thou Worm Jacob” tickled me in the King James translation, but when I read the medieval sage Rashi’s commentary on it, I licked the dust with joy. “The family of Jacob/ weak like the worm, / its strength only in its mouth.”

And, of course, in Blue Hill Avenue, I sent Rabbi Lux, in imitation of Alice in her garden, down the real hole, his toilet, where his bowels sent him for solace. That book got attention for a moment, something that I dreamed of: listed as “New and Recommended” in The New York Sunday Times. To my surprise, it resurfaced in The Boston Sunday Globe’s list of “Essential” books about New England on the 21st of July 2009. I found myself close to the bottom, but to be on a list with Thoreau, Emerson, Melville, Henry James, and Hawthorne is to be humbled. Kafka whispers about marriage (which he was unable to do) as being the “utmost a human being can succeed in,” but then qualifies this: “It is not a matter of this utmost at all, anyway, but only of some distant but decent approximation; it is, after all, not necessary to fly right into the middle of the sun, but it is necessary to crawl to a clean little spot where the sun sometimes shines and one can warm oneself a little.”

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

Listen to a discussion of Thou Worm Jacob between George Salis and Jacob Pascoe on The Collidescope Podcast:

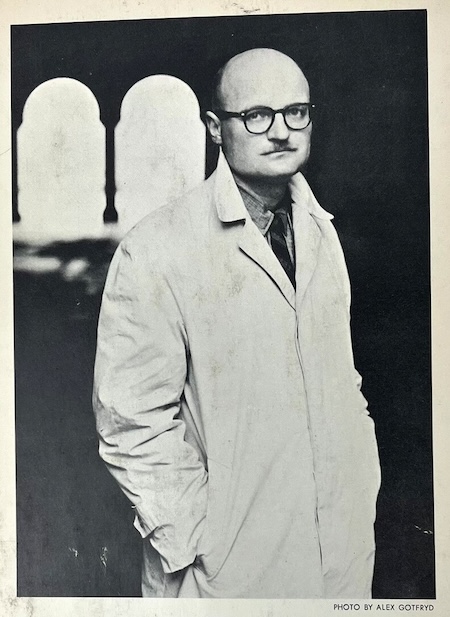

Mark Jay Mirsky, professor of English at The City College of New York, published his first novel, Thou Worm Jacob, in 1967, succeeded by Proceedings of the Rabble in 1971, Blue Hill Avenue in 1972, and a collection of short novellas and stories, The Secret Table, in 1975 with a cover by Donald Barthelme. In 1977, Mirsky published My Search for the Messiah, a collection of essays including sketches of major Jewish thinkers: Harry Wolfson, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, and Gershom Scholem. His novel, The Red Adam, was published in 1990, The 252 Absent Shakespeare appeared in 1995, followed by Dante Eros and Kabbalah in 2003, a sketch of the poet, Robert Creeley, Creeley, Pressed Wafer in 2007, and a play Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard produced at the Fringe Festival in NYC, 2007. The Drama in Shakespeare’s Sonnets, A Satire to Decay, was published in 2011. In 2014, Mirsky’s novel Puddingstone appeared, and in 2016, a memoir of Ruth S. Mirsky, A Mother’s Steps. Works he has edited include Rabbinic Fantasies—an anthology co-edited with David Stern in 1990, The Diaries of Robert Musil (1998), The Jews of Pinsk, Volume 1: 1506–1880, in 2008, and Volume 2: 1881–1941, in 2013. He’s a founder and editor of Fiction Magazine.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

One thought on “The Yoke of the Kingdom: An Interview With Mark Jay Mirsky – Part 2”