George Salis: Your debut novel, Son of the Great American Novel, is being reprinted by Tough Poets Press about half a century after its initial publication in 1971. Can you reflect on this? How do you suppose modern readers will react to it?

James Fritzhand: Half a century! My God, doesn’t that make me feel ancient? But to answer your question: I suspect most, not all, mind you, but certainly most modern readers will pay no attention at all. Their eyes will be buried in their phones, their thoughts on matters far more mundane than resurrected 50-year-old novels. But that’s all right. The very fact it was rediscovered and being republished makes me absolutely thrilled, gobsmacked, and beside myself with delight, that someone was so moved by my words, took such pleasure in my prose, that they went on a one-man crusade to resurrect the novel and hopefully find it a wider audience than it initially had. How this happened is an interesting story and one which was totally unexpected.

Last January, I received an unsolicited email that began, “Please forgive the digital intrusion! And please allow me to start by asking if you might be the James Fritzhand who wrote Son of the Great American Novel? If not, sorry to have bothered you! If you are the author of SOTGAN, I am writing just to say Bravo! Last month, I stumbled onto a mention of the book somewhere online. I was surprised that I was unfamiliar with it, as I’m a great fan of NYC-set novels of the late ‘60s. I ordered a used paperback copy and when it arrived I fell entirely in love with the book. Just tore through it. I so admired the novel that I then purchased a hardcover first edition. I’m writing for two reasons: To express my shock (near astonishment really) that the novel is not a milestone book of the era, up there with Pynchon and Vonnegut and the other great fabulists of the ‘60s.” My unknown admirer concluded with, “In any event, I just want to convey how utterly impressed I was with SOTGAN, and how surprised I am that it has yet to be seen as a classic of its time and place.” Now who wouldn’t be tickled pink to get an email like that? It was from Jack O’Connell, author of literary fiction as well as four gritty novels best described as New England noir at its finest. A correspondence ensued, and it was Jack who first approached Rick Schober of Tough Poets Press, urging him to read the novel and consider it for reissue.

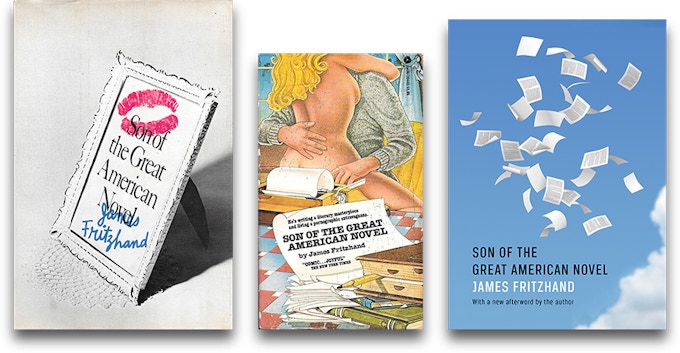

So here I am one year later, the new cover unveiled, typos and misprints corrected from the first edition, ready to send out my freshman effort to a whole new audience. Is there an audience, though? The book isn’t typical, I will say that, and I don’t mean it in a self-congratulatory way. I’ve reread it, slowly, carefully, page by page, savoring each and every word. But the mind of the twenty-something it sprang from is quite different from the mind of the seventy-something I am today. It’s a black comedy. It loves language. It finds words rich and tasty and filled with meaning. It delights in parody and pastiche. It plays with reality. Is it a dazzling performance? Maybe bright and smart are a safer bet. Either way, it’s not for me to judge. But it doesn’t take itself seriously and I think that’ its saving grace, what I hope will propel a new readership to keep turning the pages. I remember the fun I had writing it and the fun rereading it half a century (there we go again!) later.

GS: The satire and humor in Son of the Great American Novel, plus the fact that it features a hyperbolically hot-shot writer, made me think of it as a precursor to Mark Leyner’s Et Tu, Babe. The inclusion of excerpts, agent rejections, and other forms also reminded me of Gilbert Sorrentino’s Mulligan Stew. While your novel could have influenced these later works, I’m wondering what earlier works influenced or informed Son of the Great American Novel.

JF: Two novels come to mind. Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse and The Magus by John Fowles. The latter I read my senior year in college, convinced my life would change and I would be a better person because of it. The book was so tricky, slipping between fantasy and reality with startling ease. Fowles was—and always will be—an extremely talented writer, and the “eccentric masques” (Wiki’s description) and mind games he subjects his protagonist, young Nicholas Urfe, certainly left their impression. Hesse too was a writer I found compelling, so much so that I spent the better part of a year reading his entire oeuvre—those beautiful editions Farrar Straus published in the late 60s, and which I could ill afford on my $99 a week salary at the time. His Magic Theatre so intrigued me there’s no doubt its imprint remained vivid as I set to work on Son of….

GS: The humor in your novel doesn’t seem to pull any punches. Do you think humor should have limits, or is nothing sacred?

JF: Thank you for the compliment. I’ve never really considered holding back when it came to being funny—but then again I don’t think I ever specifically tried to be funny either. I certainly didn’t set out to write a funny novel. Rather, I thought I’d skewer contemporary norms, play with cultural icons, do an anatomical two-step to describe ejaculation. The truth is I didn’t believe I was a funny person until I was in my fifties when I started hearing the laughter that greeted a clever remark. Although I’ve always described my first (published) novel as a “black comedy,” reading it today unearthed some less-than-comic set pieces. One in particular required some hasty rewriting—barely pubescent youths cavorting with sheepdogs no longer half as amusing as I first imagined fifty years ago.

But now I have to answer your question. Humor does have its limits. It’s called bad taste. It’s called not being funny. It’s called cringeworthy. But it’s not up to me to decide what’s humorous. All I know is you can’t bake a cake with rancid ingredients.

GS: Is the protagonist Arden K. Hoffstetter based on a particular writer or perhaps an amalgamation of several?

JF: Nope. He’s a product of my imagination, pure and simple. Or as my mother once asked, “Where do you come up with these ideas?” I didn’t have a clue then and I still don’t today. Arden just emerged from my Smith-Corona Silent Super, full grown and coming off an acid trip. That, however, was indeed “an amalgamation of several.”

GS: Gone are the days of writer celebrities, except for a small handful of possible exceptions. Do you think this is for the best? Is there any benefit of putting writers in the limelight?

JF: I wish there were as many writer celebrities as there are name-brand actors. Tom Wolfe, Capote, Vonnegut, Mailer, just to name a few, were all bigger than life—and a hell of a lot bigger than their typewriters. But to digress for a moment. When I got my dozen fresh-off-the-press copies of Son of… I promptly sent one to Wolfe’s publisher, hoping they’d forward it to him. And they did. About a month or so later I received a handwritten letter postmarked Rome, thanking me for the book and wishing me success. Although he never said if he liked it or not, I did love every page of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and Bonfire of the Vanities.

As for putting writers in the limelight—of course there’s a benefit. It gets people to read. A couple of years ago I was on the subway in Montreal, headed for Schwartz’s for a smoked meat sandwich. I looked around the car and no eyes met mine. Why? Because everyone was reading. I was on the IRT this past summer. Not a page was turned, not a Kindle in evidence. No wonder I’ve always referred to Canadians as civilized.

GS: It seems that humorous fiction is rarely if ever taken as seriously as other types of fiction. Do you think this is a mistake?

JF: Vonnegut was taken seriously and he was considered funny. Philip Roth liberally employed humor and no one ever called him second-rate. Bruce Jay Friedman, Max Apple, Steve Stern, Tom Robbins, Charles Portis, William Kotzwinkle, Gore Vidal, Joseph Heller. They’ve all made me laugh. Does that mean they’re “unserious” novelists? I don’t think so. Andrew Sean Greer’s Less won the Pulitzer, a Bechian character if ever there was one. But humorists do seem to have a shorter lifespan than other novelists. I mean, does anyone still read James Thurber or Ring Lardner, and I mean neither of them disrespect? Tastes change. What made our parents and grandparents chuckle often fails to elicit a titter today.

GS: You switched to working in TV in the 80s. What can you tell me about this experience? What are your thoughts on the introduction of AI for scriptwriting and other creative aspects of making TV shows?

JF: I wrote for television in the 80s and 90s, culminating in sixty-five half-hour episodes of a syndicated series based on Valley of the Dolls. After the work dried up I left L.A. and in so doing left that part of my life behind. I wrote “one hour dramatic” as it was categorized at the time, i.e., I didn’t write for sitcoms although years later (when I thought I was actually funny) I regretted limiting myself to one genre and not the other. Writing for television was glorious. Watching your words come alive onscreen is unlike anything associated with writing fiction. But writing prose is private, just you and the keyboard and the glowing screen. Writing for television turns that on its head. It’s a collaborative medium, and script writing a collaborative effort. You get notes on an outline. You finish a script and you sit in a room with your fellow writers and you get more notes. You do another draft incorporating everyone’s notes and then you send the script to Aaron Spelling and Doug Kramer and the notes keep coming. And all through the process you’re smiling and putting your ego aside and remembering what your father once told you, “Laugh all the way to the bank.” So was it just for the money? Well, to be quite honest, I made more money in three weeks writing an episode of Hotel than I did working six to eight months on a novel. And I did get to write an episode for Elizabeth Taylor and Roddy McDowall, and yes she was gracious and yes she was remarkably beautiful. But all good things must come to an end. By the time I was fifty I was no longer the new kid on the block; “the flavor of the month” was the phrase you’d often hear. The networks came close but ultimately passed on our series idea, a post-apocalyptic sci-fi Western mashup called Fort Nowhere. My writing partner and I had a falling out. My mentor dropped dead on the tennis court. A couple walked into our house and offered to buy it for a ridiculous amount of money. It was time to move on.

I know nothing about AI. I haven’t paid any attention to all the articles written about it. I consider myself a Luddite. Just going from Windows 7 to Windows 10 was traumatic. I still listen to music on CDs. I only recently learned how to stream. However, I have mastered the art of applying for visas online.

GS: What’s a novel you think deserves more readers? Why?

JF: This one I’m well prepared for. I’ve done my research, racked my brain. Sorry, but I can’t limit it to one. In fact, I have a list (in alphabetical order):

- A Lost Lady by Willa Cather

- The Eighth Day by Thornton Wilder

- The Golovlevs by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin

- The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosinski

- The Rector of Justin by Louis Auchincloss

- The Story of Harold by Terry Andrews (George Selden)

I wrote but never sold a script about the young Willa Cather. Willa in Love. I’ve read all her fiction, and this slim brilliant novel stands out as quintessential Cather. The imagery and concise pointillistic prose never cease to delight. The woodpecker blinding still makes me shudder.

Thornton Wilder’s last two novels, The Eighth Day and Theophilus North, are a warm bath of nostalgia—old-fashioned in the best sense of the word.

Sophomore year in college the housemaster of our dorm was a graduate student in Russian literature. He was doing his dissertation on what he termed “the minor Russians” and recommended The Golovlevs. Published in 1880, this tale of an incredibly venal and dysfunctional family has clearly withstood the test of time (terrible cliché but true all the same). I’ve always thought of the Golovlevs as the proverbial nest of vipers, Lillian Hellmann’s Little Foxes of the steppes. The novel’s hefty dose of nasty Russian realism has stayed with me over the years, so much so that I ended up writing a “Russian novel” of my own, Four Sisters, just to satisfy the itch.

Jerzy Kosinski’s brutal descent into wartime depravity seems to have been forgotten by today’s readership. I don’t know why I’m attracted to grim subject matter, but this is a harrowing novel and one deserving a new audience. Initially greeted to great acclaim, and later to considerable controversy, it’s a work that stays with you long after you’ve read the last page.

Louis Auchincloss is another writer whose entire (and prolific) oeuvre I’ve devoured with equal parts gusto and delight. A chronicler of the upper classes, he’s infinitely more readable than Wharton or Marquand. The Rector of Justin is Auchincloss in top form. Of all his novels, and there were thirty others, this one is the crown jewel and certainly my favorite. It’s a tale about the charismatic founder and rector of a private boys’ school. Deftly employing multiple points of view…but no, you have to read it for yourself.

Lastly, The Story of Harold by Terry Andrews, a.k.a. George Selden. It made such an impression on me at the time (1974) that I had my agent literally beg a colleague at Holt, Rinehart, to forward my fan letter to the author. Truth is, after reading the novel I’d decided that if I met Terry we’d immediately fall in love and live happily ever after. I had no idea Terry Andrews was a pseudonym for George Selden, a wildly successful children’s book writer. He actually replied to my letter and even accepted my invitation to dinner. I remember arriving at the Hunan restaurant I’d chosen, shaking his hand, pouring the tea, and knowing right from the start that after the evening was over and the fortune cookies broken, we’d never see each other again. George was a very sweet man but the two of us were not destined for a fairytale ending. But his novel is so unique, so filled with heartbreak and humanity, that it’s a terrible loss to have been forgotten. Try to find a copy because you won’t be disappointed.

GS: Why did you stop writing novels after switching to TV? Are you writing anything at the moment? If you’re not writing, what have you kept busy with other than your TV work?

JF: Writing for television was a full-time job. There just weren’t enough hours in the day to even consider working on a novel. However, during the lengthy Writers Guild strike in 1988, I set to work on one—darkly comedic, yet again—about my experiences writing Hotel, about the temperamental ex-film star (Anne Baxter) who took over after the sudden death of her predecessor, another temperamental ex-film star (Bette Davis), about the Machiavellian producer (Doug Kramer) who loved setting fires so he could put them out, about my boss (Aaron Spelling) and his aspiring actress daughter (Yes, I wrote a script for 13-year-old Tori and she was terrific), about the head writers (Bill and Jo LaMond) whose assistant found me in the slush pile and turned my life upside down, with yours truly cast as a Candid-esque innocent, observing it all, navigating one potential pitfall after another, and emerging with a couple of cuts and bruises but basically unscathed. I thought it was whip-smart and destined for the Times best-seller list. Wasn’t I naïve? My agent was less than enthralled, and Hoffstetter’s Revenge (the surname recycled) failed to find a safe harbor, languishing on my shelf until consumed by the flames of the Tubbs fire of 2017.

I tried again a decade later. Full Moon Blues was a comic caper about a Jewish werewolf on the lam, hiding out in Disneyland after being wrongfully accused of being a serial killer. He may have been guilty of smacking his lips at the sight of a Pomeranian, but that’s as far as his killer instincts went. I thought the transformation scenes when he “wolfed out” were brilliant, as were the interstitial chapters detailing the exploits and misadventures of his lupine relatives, the bilberry-obsessed uncle in Tsarist Russia my particular favorite. Again, no takers.

What’s kept me busy since then? I’m a fanatical birder, a world lister, determined to see all eleven thousand species before my knees give out. I’ve dragged my partner to Indonesia, New Guinea, Ethiopia, Ghana, pre-homophobic Uganda, Madagascar, Chile, Argentina, Cambodia, India, the Andaman Islands, Brazil, Peru, Mexico, Costa Rica, China, Borneo, and next month Vietnam. I love the treasure hunt in search of rare and elusive birds, the long days, the planning and the carrying out. When I’m birding, I don’t have time to think about rejection slips and unsold novels, the awful experience writing for As the World Turns, the manuscripts lost in the flames, the way my career didn’t turn out exactly as planned. My first novel is about to be republished. My husband and I will celebrate our 48th anniversary this summer. We had a good crop of tomatoes and I can’t keep up with our Cara cara. I have no complaints.

GS: I’m curious about your rarest, most noteworthy avian encounters.

JF: Picture a bumpy, dusty road in southern Ghana. Weaver nests hang from the trees like forgotten Christmas decorations. Guinea fowl scratch for tasty bits along the roadside. The sky is cloudless and shockingly blue. It’s March 2016 and we’re headed for the village of Bonkro, three hours distant, there to embark on the hunt for the White-necked Rockfowl, otherwise known as Picathartes, as bizarre looking a bird as any I could imagine, and one I’m desperate to see. When we finally arrive in Bonkro we’re greeted by a dozen little kids, and yes, I wink at several and play at being a lion on the prowl. Rewarded with giggles and laughter, our group heads into the forest in search of our quarry. After climbing up a steep incline half a mile later, we crest a ridge and find our way blocked by a wall of tumbled boulders and a cavelike opening. It’s here the Picathartes will spend the night, so we take our seats on a narrow wooden bench the villagers have placed here and wait. And wait. And wait. Our vigil seems endless, but forty-five minutes later, the bird is suddenly there. Weird is the watchword—about the size of a chicken, the Picathartes has a stout black bill, a bright yellow face, and wears what looks like a pair of dark-brown earmuffs, distinctive cheek patches that only add to its overall strangeness. White underparts and a grey-black back complete the picture. Strangest of all, you can’t tell if the bird has feathers. Its contours are so smooth I think of a plastic chicken and the image has stuck with me ever since. A moment later, a second bird flies in. Apparently they sleep in their nest each night even when there aren’t any fledglings to rear. We can’t see the nest but the two birds hop around each other, then retreat into the rear of the declivity. Our group expels an astonished breath. We look at each other and shake our heads in amazement. “That had to be one of the best birding experiences of my life,” I tell our guide. I’ve seen great birds since, birds so rare they may be extinct by now (Liben Lark), so beautiful you can’t tear your eyes away (Ruspoli’s Turaco), so elusive and hard to see that when you finally catch a glimpse you can’t believe your persistence has paid off (any number of Pittas, new world and old). But for the sheer wild oddity of it all, nothing beats the White-necked Picathartes.

GS: Did you ever dream of, or make a serious attempt at, writing The Great American Novel, something in the vein of your protagonist Arden K. Hoffstetter’s mammoth work, Flush?

JF: Ah, the last question. the final turn of the screw. Writing “The Great American Novel” was never my goal. But I did write a real doorstopper, a 500-page roman à clef about Walt Disney. American Dreamer required a huge amount of research into animation and early Hollywood. I had a silent film star as a love interest, using the template of Disney’s career but creating an entirely fictional character, warts and all, to hang the story upon. Jed Farley and Cordie Aspinwall, a big old-fashioned love story about two strong-willed, ambitious characters, a half-century tortured romance with a Hollywood ending. Delacorte bought the novel, and one month later asked to be released from the contract, their legal advisors fearful of a lawsuit. Despite the fact there was nothing defamatory about my portrayal of Farley, they didn’t want to risk litigation. Worse was to come because my agent was unable to place it elsewhere. It too is gone now, thanks to a downed power line and flames fueled by 80-mile-per-hour winds.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to reminisce. Perhaps your readers will search out some of my fiction. Starring, Third Avenue, and Four Sisters are my personal favorites. In 1977 The New York Times accused me of being an “ex-serious novelist” and had this to say about Starring: “Fritzhand is not to such hackery born. His frequent flashes of wit and nicely turned dialogue read like winks at his readers.” Just to set the record straight, I have never put my name on a book I wasn’t proud of. I have never winked at my readers. In fact, I only wink at little kids and toy poodles, and not all that often.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

The Collidescope is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through those specific links and make a purchase.

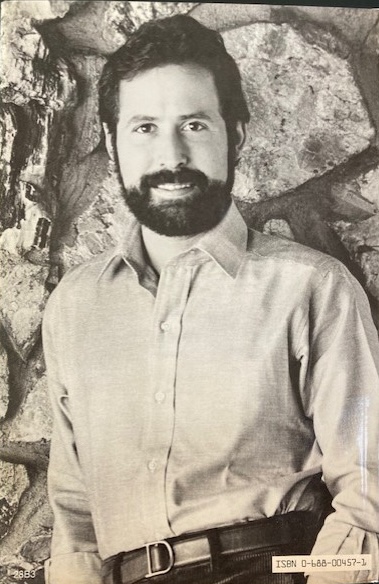

James Fritzhand was born in Brooklyn, graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a B.S. in zoology, quit medical school after one week, worked as a social worker in the South Bronx for three years, and sold his first novel in 1970 at the age of 24. He went on to write twenty novels of popular fiction before becoming a television screenwriter for such prime-time series as Trapper John M.D., Flamingo Road, Falcon Crest, and Hotel. He currently resides in the Napa Valley with his partner of nearly fifty years. An avid birder, Fritzhand’s life list is fast approaching 6,000 (IOC, seen only).

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. He’s the winner of the Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.