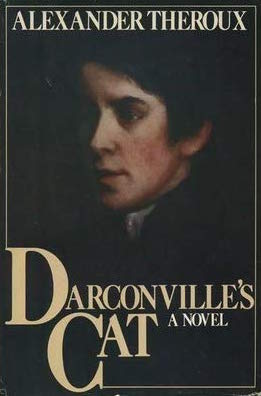

About Alexander Theroux: “Alexander Theroux is a writer who resists classification. His first book, Three Wogs (1972), is a triptych of novellas that examined the class and racial conflicts that occur between the archetypal Londoner and the inhabitants of the British Isles, the “wogs,” who are “not one of us.” This exceptional debut received a nomination for the National Book Award. Theroux’s second novel, Darconville’s Cat (1981), is widely considered his masterpiece. Anthony Burgess hailed it as one of the best 99 novels written in English since 1939. Darconville’s Cat is an exquisite novel of revenge and thwarted love. It too was nominated for a National Book Award. An Adultery (1987) is a detailed, fictional character study of the sin in question in a contemporary New England that still manages to evoke the echoes of its Puritanical past. Theroux has also published two widely regarded books of essays, The Primary Colors & The Secondary Colors (1994 & 1996), along with a collection of poems, The Lollipop Trollops & Other Poems (1992), as well as two monographs and several books of fables. Laura Warholic, or The Sexual Intellectual, published by Fantagraphics, [was] Theroux’s first novel in twenty years.”

I interviewed Alexander Theroux here.

“Art creates the Eden where Adam and Eve eat the serpent.”

Darconville’s Cat is literature incarnate. Half of it could be bound with human skin, the other half with the fatty stools from a cystic fibrosis tryst, glazed with lovejuice jizzum. For the book is the body and the pages are the brain, crackling with emotional intellect and intellectual emotion.

I came to this book having my biases and expectations, including that this is revenge fiction, and in a way it is. In the film Nocturnal Animals, a writer creates a novel so unsettling it disturbs and haunts his ex who must get in contact with him, either for comfort or envy of his accomplishment or both, but that was southern gothic fiction in the vein of William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy, and it was a film about a book and its effects. Darconville’s Cat, on the other hand, is partly that book and then some, capable of invoking envy and shock and awe and sorrow and more. If this tome is the epitome of revenge fiction—“victory without blood [is] twice achieved…”—it’s because one could easily imagine the spurner Isabel Rawsthorne, who has an involved relationship with her college professor for about 4 years, reading this a decade or more later and feeling puzzled, nostalgic, appalled, despondent, maybe even regretful, etc. But there is more love here than hate, for to sustain this creative effort and to realize it as such requires at the very least a love of life and consciousness beyond one’s own, and whether Darconville-Theroux still cares for Rawsthorne-Anonymous is somewhat beside the point. Never does it slip into solipsism, though it does reflect dejection via rejection and delusion however temporary or prolonged, yet there’s a palpable catharsis by the end of the novel. (And the whole of the work is not without its generous helpings of humor too, roasting as Darconville does hillbillies, the school faculty, and more, with the chapter titled “The Garden of Earthly Delights” being one of the funniest I’ve read in all of literature.)

And of course there’s the greatest love of all in this novel, the love of words, and words are nothing without a collective consciousness of them and in this way Theroux is an admirable, heroic even, preservationist of endangered words, a resurrectionist of extinct logoi, and a demiurge of vocabulary that has never existed but has had an urge in that mute void to come into fruition, plucked and molded by Theroux, almost as if “words were all he had left.” And during a time when Alaric Darconville can’t work on his hagiographic book of angels given the nearly palindromic title of Rumpopulorum, seraphs that manifest throughout the novel, including Uriel, he has a nocturnal meltdown: “In The End Was Wordlessness”—aphasia, the only true apocalypse—yet Theroux staves off that End by giving life to the lingual, life to life. Those who recoil at the verbosity should truly ask themselves at what point did they decide that they had learned enough words. To limit vocabulary is to limit all else, including knowledge and expression. Based on this book, Theroux has an almost maniacal lust for life that cannot be manacled even as Darconville loathes much of what can be seen in his fellow humans, but perhaps the loather is more in tune with what human beings are capable of feeling seeing doing and thus regresses emotionally or reacts negatively in response to the omnipresent primitive and dull. Indeed, the irony of the misanthropy is that it is delivered in such a linguistically vibrant way that it infects one with a passion for life. The vocabulary and allusions nearly outdo Ulysses, definitely the former, while also referencing it in a sly way (“yogibogeybox-shaped head”), to a degree that even the simple sentences are quite evocative. Word drunk doesn’t even begin to describe it but you could very well become inebriated yourself on the inundation of outdated and mandated and fecundated and adumbrated and appropriated words: geloscopical, kalkydri, post-lapsarian, solisequious, malneirophrenia, ignivomous, chantepleure, rosydactylate, panmoronium, chrysopoetic, zielverkooper, cataphatic, vivisepulture, agathokakological, balatron, pornofornocacophagomaniacal, ambisinistrous, and of course lopadotemachoselachogaleokranioleipsanodrimhypotrimmatosilphioparaomelitokatakechymenokichle- pikossyphophattoperisteralektryonoptekephalliokigklopeleiolagoiosiraiobaphetraganopterygon. (Finding these words, I imagine Theroux combing through dusty tomes, “leafing through lexicons,” and handling medieval manuscripts so fragile that they could disintegrate if you looked at them the wrong way.) It’s true, “I never metamorphosis I didn’t like.” And we meet many morphing words—met him pike hoses. And while there are innumerable beautiful sentences to be found in this literary world in which crows say “actaeon! actaeon!” and schoolgirls are named Pengwynne Custis, this one stuck out to me as positively Pynchonian and an example of the delights of literature: “Olivia Oona Osborne, going stone cold, suddenly dropped her jaw and her tenth cup of cheap bourbon and reeled over backwards at the top of the staircase, the egglike alliteration of her name matching the echoing wail as she bounced, bum over beezer, all the way downstairs with a loud dopplerian ‘Ooooooooooooo!’”

Perhaps Darconville is guilty of being hyperbolically idealistic and romantic, for he had been “a little boy whose earliest memory was of trying to pick up pieces of moonlight that had fallen through the window onto his bed.” It’s a question of dreaming too much versus too little. The dichotomy of Darconville and his ‘cat.’ (Don’t forget that when Darconville was six, “he won the school ribbon for a drawing of the face of God” and that “it resembled a cat’s.” A feline theophany loaded with nine lives and four shadows.)

The emotions of love and heartbreak and hate are so finely wrought without being cliched that they surely sprung from a source of sincerity, from the élan vital, tilting toward an almost “cosmic perspective on love and hate.”

Here is but one example of the anguish: “Something rose out of him and actually looked down at himself from the ceiling, from the sky, and then from beyond the universe, making him feel smaller than anything that ever was in the world.”

For a novel centered on a love affair, on a single relationship—“the story was simple, a fable about Isabel Rawsthorne and himself: doubt is double”—the novel still manages to be maximalist in its own way, not only via vocabulary and sentences that respire but also details that allow us different perspectives, however minute or not, such as a list of students’ essays’ titles with corresponding grades (the one titled “Three Wogs: My Favorite Novel” by Analecta Cisterciana received an A, as is the dessert of those with copro-dusted proboscises) as well as Isabel’s introduction to hers, minor characters woven into existence through major descriptions and major tics, an enchanting digression on ears, yin-yang essays on love and hate, a horrifically epic list of sadistic fantasies, a lengthy prayer against perceived feminine threats across history and culture, the cataloged contents of a misogynist’s library, and more.

Regarding the library, I began to wonder, what would be in the misandrist’s library, Ms. Crucifer’s, if you will?

This is what I came up with (feel free to make suggestions): DFW’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, Anna Kavan’s Ice, The Koran, The Blazing World by Siri Hustvedt, John Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom: A Tetralogy, Isabel Allende’s La casa de los espíritus, Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, Lucy Ellman’s Ducks, Newburyport, The Holy Bible, Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories, Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy”, Vladimir Nabokov’s The Enchanter, Helen DeWitt’s Lightning Rods, Rikki Ducornet’s Netsuke, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian: or The Evening Redness in the West, Save Me the Waltz by Zelda Fitzgerald, 1984 by George Orwell, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tail, The Wave by Evelyn Scott, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, the works of Kathy Acker, Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis, Eimear McBride’s A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, Memoria de mis putas tristes by Gabriel García Márquez, the ashes of Sylvia Plath’s final diary, Lord of the Flies by William Golding, We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, The Hobbit, or There and Back Again by J. R. R. Tolkien, Daring to Drive: A Saudi Woman’s Awakening by Manal al-Sharif, Christopher Hitchens’ “Why Women Aren’t Funny,” the works of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemmingway, Women Without Men: A Novel of Modern Iraq by Shahrnush Parsipur, The Art of War by Sun Tzu, Marguerite Young’s Miss Macintosh, My Darling, the femicidal “Part About the Crimes” in 2666 by Robert Bolaño.

Some thoughts on the sadistic fantasies which are suggestions from Dr. Crucifer to Darconville: these iron maidens about an iron maiden range from the creatively horrific to the humorously horrific. An example of the latter: “Decapitate her, mesh her mouth, and make her head into a radio!” And an example of the former: “Cut a spot in her breast and place a window before her heart as an aquarium for stinging butterfly cods!” Of course, the creative and humorous horrors overlap, and there’s this one: “Strip off portions of her skin, paint them, and then use them for tiny kites!” That suggestion in particular must strike Darconville as an inversion of pure heaven into pure hell because during the height of their romance they had flown kites together. In all, many of the suggestions use specific verbs that sound either medical or archaic or both, and truly ominous as they are cartoony, such as “Sigmoidoscope her,” “Vapulate her,” “Conculcate her,” and “Infibulate her…”

Dr. Crucifer, the desexed demon who is diametrically opposed to females, a rotten villain superbly wrought and memorable for his ability to be the gelded mare on your sleeping chest, conductor of your darkest dreams, is the “shady and insane” creature that feeds on and fans the flames of Darconville’s doubt and hurt and hate, starting with changing Darconville’s outlook on the looks of his lost love, explaining that he “saw nothing but a pudgy self-preening angel of banality with ankles like bottles, scarce twenty-odd years above the girdle, and some fifty beneath. Hodgepudding! Globuliferous pig’s-trotters! A pippin grown upon a crab!”

The irony of the iron-named Dr. Crucifer is that “he had tits” and “his hands were pudgy, with dimpled knuckles, and his fingers were long and groomed like a woman’s, the nails left sharp and cut almost to a triangle.” And when he screams, as he is wont to do, it’s described as “a woman with a man’s voice and a hyena in her womb.” Since desexed, he becomes a combination of both sexes, androgynous. I couldn’t help but think of Darconville going to the dark side, especially when Darth Crucifer gets a tad too excited: “‘Kill them all!’ he screamed, biting the air in the fullness of his malice. ‘Kill them all!’”

Taking a turn in the topic, I was led to believe that the novel might be comparable to Lolita, which it’s not, except that they’re both masterfully written and while one relationship, if you can even use that word in such a context, is illicit and pedophiliac, the other could be frowned upon because of an age difference that is at the very least legal—29 with 18 versus 36/37 with 12—but Darconville could be asked why he has found a connection to the forming and relative formless mind of a young woman rather than one who is, if not his own age, at least near his level intellectually, and one could make suppositions, for early on he “wondered if she were simply the result of his own curiosity about himself, as he might be for her.” The professor could also be accused of abusing his power as an authority who is supposed to instruct these women, not in any way destruct them. Aside from age, another major difference is the consensual nature of the relationship, the pursuit on part of Isabel who leaves a pomander ball on her professor’s doorstep with a note reading “For the fairest,” and thus the ball might as well be a golden apple, for “they were the three words that had started the Trojan War.” Not to mention, the sex in the book, which is by no means an immediate ‘achievement’ in the relationship, is described in the most romantic way possible, which could speak to some kind of hyperbole or delusion on part of the describer—“maybe she was simply the product of his own temperament”—but cannot be deemed the invention of a lecherous mind:

“And they made love in the naked darkness, two lost children looking for rebirth in the glory of each other, struggling upward, like their wayward kite, toward the cold particulates of one world where, joining sky and sea by song, they found another, and then reaching up higher still to behold in the frost and starlight the very beauty of very beauty, neither begotten nor made but being of the substance and essence which is beautiful unto all eternity, they made a wish, stretched forth and—poof!—blew out the birthday sun, and were blind at the climax of vision.”

Compare that climax which is not the novel’s climax as such to the description by Humbert Humbert himself of his demoniacal deeds, even before the full consummation of his pedophilia, during a scene where he surreptitiously masturbates while in contact with the ‘nymphet:’

“…and every movement she made, every shuffle and ripple, helped me to conceal and improve the secret system of tactile correspondence between beast and beauty—between my gagged, bursting beast and the beauty of her dimpled body in its innocent cotton frock […] With the deep hot sweetness thus established and well on its way to its ultimate convulsion I felt I could slow down in order to prolong the glow. […] her teeth rested on her glistening underlip as she half-turned away, and my moaning mouth, gentlemen of the jury, almost reached her bare neck, while I crushed out against her left buttock the last throb of the longest ecstasy man or monster had ever known.”

Both passages are ensorcelling from a literary standpoint but the latter is also horrendous in its blatant perversion and obscenity, and it’s not even explicitly graphic, which in its roundabout way perhaps adds to the ghastliness of it all.

And while Darconville does notice Isabel’s subjective beauty, his details still remain fairly romantic and abstract rather than focusing on any “sloppy anklet” or worse, although there is the moment when he watches her practice archery from afar and “could almost feel the sweet perspiration on the glistening down of her cobnut-colored arms, flushed with each triumph, shot after shot.” Plus, whereas Dolores codename Lolita is a voiceless victim, Isabel is given her say, more or less. She is not just an object of pleasure even though her disposition does seem fairly dull, almost craven, yet surely immature.

I’ll leave you with these intriguing juxtapositions of phonetic explication: “Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.” (Keep in mind that it’s not low-lee-ta but law as in lollipop.) From the essay on hate: “Hate! Say the word: how the mouth, shaped to sarcasm, fakes in an adventitious bark what, exhaled, becomes a râle of shuddering repugnance swiftly cut in two by the rapiered T that snaps the entire face shut without one movement of the lips.” From the essay on love: “Love! Say the word: how the velarized tongue drops, astonished, to the sigh of a moanworthy O that comes from low in the throat and trembles into the frail half-bite that closes on it like a kiss!”

In toto, we learn that love loves to love love but hate loves to hate love, which tells us that hate loves. Ergo, love hates.

(That this novel is out of print and neglected is a mark of shame on the face of literature. It has been suggested that the misogyny in the book, which is clearly a product of one of the darkest and most hateful characters in literature, Dr. Crucifer, whom the protagonist calls insane and inhuman, is the chief cause of its being out of print. In my interview with Steven Moore, he had this to say: “Readers know that a good actor can play a hero or a villain, a virgin or a virago, but they’re reluctant to believe that a novelist is likewise playing a role when writing.”)

Editor’s note: The aim of Invisible Books is to shine a light on wrongly neglected and forgotten books and their authors. To help bring more attention to these works of art, please share this article on social media.

For early access to literary content like this and other awesome benefits, consider supporting The Collidescope on Patreon.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter, and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.

Much appreciated, Rick.

LikeLike

Out-bloody-standing, George! Never have I wanted to put off life’s demands and shack up with a book in a hideaway so badly in my life!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your comment, Chris. I’m glad to have that effect on a reader of your caliber. As you know, I don’t have Instagram but I stumbled on your photo of my novel with all the sticky notes peeking out of the top and thought to myself, This is a reader who is too good for this earth. lol

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is extremely kind, George! I’m going to link to this review in my video about Theroux (mainly his Metaphrastes essay) that I plan to make tomorrow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You just reminded me, last night my mind was wandering and a similar idea came to me, of creating a sort of two-way road of content. I’d of course be happy to return the favor and link your video at the end of my article. In the future, I’ll be on the lookout for more crossover opportunities. By the way, I shared your review of Brightfellow with Rikki. If she watches it, I’ll let you know what her reaction is. : )

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have corrected the oversight you pointed out. The Recognitions Book Club and I are doing this sort of thing right now with our reading of 2666. I’m up for whatever. Just let me know!

Oh, no! When I made that video I never dreamed Madamoiselle Ducornet would see it. Deep breaths, deep breaths.

LikeLike

Just came back to reread this now that I’ve got the majority of the novel in my head, and I am blown away at how good this review is. You truly have a gift, George. There are several overlaps that I am going to omit from my video because you’ve articulated/presented them far better than I could hope. I’m being sincere here, not pity-phishingly self-deprecating. There is also overlap that I am still compelled to present (e.g. the connection to the opening lines of Lolita and the essay on love). Anyway, again and again, more cheers for this review. Superlatives fails me and I haven’t the skills to combine segments of Greek and/or Latin as Theroux can.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! Some of your review magic must have rubbed off on me. Your words fuel me to do more, my friend (I hope Gaddis makes me giddy). And when the glorious time comes to release our books of reviews and essays, we must go on a joint book tour. ; )

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Her name was and is Olga Olegovna Orlova—an egg-like alliteration which it would have been a pity to withhold.” Nabokov’s The Real life of Sebastian Knight. Looks like he adores Nabokov. Now that he used him ten thousand times.

LikeLike

Books are made from books are made from books, my friend. Thanks for pointing this out. And indeed, he loves Nabokov. Cheers!

LikeLike